The Monetarists versus the Keynesians:

There are conflicting views on the mechanism as to how money supply affects the general economic activities or income level.

On the one hand, some theorists put the emphasis on a direct relation between the money supply and expenditure.

On the other hand, there are some who argue that it is by changing financial conditions particularly the rates of interest, volumes of lending and borrowing— that the influence of money supply on economic activities can be judged.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to the former school, an increase in the money supply means that some money holders will have excess money balance in their asset portfolios. In the process of restoring equilibrium these balances will be converted into the real goods and services either directly or through the intermediation of financial institutions. The pressure of demand for more goods and services will stimulate output and encourage price rises until the value of the output has risen in proportion to the increase in the money supply.

This school is called the ‘monetary school’ and gives no special emphasis on the rates of interest on the financial assets. The other school points out that the increase in money supply will affect the rates of interest and emphasize that a change in the money supply will affect cost and the availability of the credit.

A fall in the rate charged to borrowers may stimulate consumption and investment directly, or a general easing in financing conditions following a rise in money supply may encourage financial institutions to make funds more readily available to potential borrowers.

The superiority of ‘monetary over Keynesian models has not been demonstrated. However, monetary factors are not unimportant; there is no reason to reject the view that changes in the money supply will affect income either directly or indirectly via changes in interest rates or the availability of credit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Advocates of monetary approach have not yet shown that the changes in money supply have a reliable and predictable effect on expenditure, even the direction of causation between the money supply and income is at issue. In fact, we need not give to the money supply any special significance in the financial mechanism, we need not attribute to it any special direct causal influence on economic activity, and we need not believe that the monetary authorities adopt any very simple mechanism for its control.

Nevertheless, it is also obvious that we cannot dismiss the money supply and other financial factors as unimportant in the determination of economic activity; rather it is to be understood that interest rates and the supply of credit may have a considerable impact on economic activity and that the monetary authorities have the ability to control these variables.

The most interesting event for a very long time in the realm of economic ideas is the way in which the post-war form of Keynesian economics has been challenged by a new school of thought called ‘monetarists’ led by its leader, Milton Friedman of Chicago University. A debate continues to exist between one group which places major stress on fiscal policy as the primary engine of growth and economic stabilizer and a second group which feels that money and therefore monetary policy is the most important primary factor in growth and economic stability.

Economists disagree about the nature, the history and the boundaries of the debate or controversy. The first-stage is that of taking extreme positions. The fiscalist position is that ‘money does not matter’ (or only fiscal policy matters) as an effective means of demand management. The extreme monetarists position is that ‘only money matters’ (or fiscal policy does not matter) as an effective means of demand management.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The second stage of the debate identifies the areas of disagreement more clearly and the concessions which the extreme positions are prepared to make—the fiscalist position or concession is that ‘money matters very little’ and the monetarist position or concession (to the other camp) is that ‘money matters mostly’ as an effective means of demand management.

The third stage of the debate identifies a compromising element—the post-Keynesian position is that ‘both monetary and fiscal policies matter’, we need a mix of the two but the monetarists position is that ‘money matters mostly’. Milton Friedman of Chicago and his followers assert that the authorities have no more than a temporary power to influence output and employment and that the difference between high demand and low demand policies affects in the long-run the price level along (leave aside, for the time being, the balance of payments).

According to I.S. Ritter, “Each baby girl and tiny man, that is born into a family nest, is either a little Keynesian, or else a little monetarist”. Presidents of the USA had been using following different approaches in economic policy making, from time to time, depending on whether their orientation is/was Keynesian—or monetarist. As a Keynesian, they would press hard the Congress for countercyclical tax and expenditures. If they were a monetarist they would spend more energy in trying to influence the actions of the Federal Reserve.

The Eisenhower administration had essentially a monetarist stance, while the orientation of economic policy under Kennedy and Johnson was primarily Keynesian. The Nixon administration appears to be middle of the road. Jimmy Carter, the president of the USA adopted a Keynesian policy by announcing tax cuts and increased public expenditures to remedy economic ills of unemployment.

He included L.R. Klein, the noted Keynesian amongst his economic advisors. President Reagan in 1980s is not following a different policy either—though the economic policy followed by him in USA is popularly called ‘Reagan Economics’ ; with emphasis on supply, tax cuts and incentives for production.

Practical Policy Implications:

The policy implications between the Keynesian incomes-expenditures approach and monetarism are important for the economy. The modern quantity theory (monetarism) has also close relation with classical economics in the sense not because it lays stress on the importance of the money supply, but also because it goes back to the classical idea that a market economy is not essentially unstable. In other words, the economy has a natural tendency to move along a trend path of output determined by growth in its productive potential.

Certain events outside the economic system like wars, strikes, droughts, changes in expectations and preferences, change in foreign demand do cause variations in output and employment around the trend path. But they are of short duration and the basic stability of the economy is brought about by the market forces.

The monetarists also hold the view that these exogenous factors alone do not cause the fluctuations in income, output and employment as the mismanagement of money supply by the monetary authorities— they consider this type of a government action as the cause rather than the cure for short-term economic instability. This viewpoint of the monetarists is in sharp contrast to the Keynesian view point.

According to the latter school of Keynesians, the government should play an active stabilising role not by varying taxes and expenditures, but also by such actions which will influence both private spending for consumption and investment paving the way for stabilisation. Professor Friedman stressed the basic essential monetarists idea in 1967 in his presidential address to the American Economic Association while talking of the ‘natural rate of unemployment’—a rate determined by relationships amongst underlying real factors such as real wages, the rate of capital formation, technological changes, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is his confirmed belief that the economy will over time adjust to the level of output and employment determined by the rate of growth of these underlying real factors. He also believes that this process is very simple except when disturbed by outside forces, including government. In other words, the clear practical implication of his analysis is that changes in any of the important real aggregates of the economy are beyond the reach of the short-term policy instruments of government, fiscal or monetary.

Given the stable demand function for money and given also the strong belief that only such nominal variables as GNP and price level are affected by money supply, the money alone becomes the appropriate policy instrument for affecting economic activity. Central bank control of the money supply in monetarist’s view is the single most powerful factor to influence the level of economic activity than fiscal measures involving changes in taxes or public expenditures.

But according to Professor Friedman there are considerable time lags of uncertain length between changes in money supply/stocks and the variables affected by such changes, including the price level. He says we cannot correctly predict what effect a particular monetary action will have on price level and when it will have that effect.

Attempting to control directly the price level is, therefore, likely to make monetary policy itself a source of economic disturbance because of false stops and starts. The time lags being the real rub, the central bank should not attempt to follow a countercyclical stabilization, policy of changing the money supply/stocks in response to the current economic events.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He, therefore, advocated a monetary rule of increasing the money supply between 3 to 5 per cent a year for smooth growth of the economy while ignoring the other types of disturbing economic events. This has been and remains the essence of policy recommendation of the modern quantity theory of money called the monetarists school.

The Consequences of Monetarist Challenge:

This type of monetarist approach called the ‘Monetarist Counter Revolution’—gave rise to prolonged controversy for more than two decades and there appears to be no end to it.

Although several major issues have emerged and have been clarified, if not resolved—issues yet important to both the monetarists and the Keynesian school are as follows:

(i) The question of whether the changes in the money or the changes in autonomous expenditures in the Keynesian sense are most important in explaining short-term changes in output, income, employment and price level; (ii) The basic stability of the demand function for money—a matter primarily of stability of velocity; (iii) The interest elasticity of the demand for money ; and (iv) The ability of the central bank to control the money supply.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Basically still unresolved, the econometric models, exercises, and empirical tests devised to date have not been able to establish conclusively whether the money supply or the Keynesian autonomous variables are the important determinants of changes in output, income, employment, and the price level.

Certainly, the debate will continue, as the advocates of monetarism plead that money is the key to these changes in the economic system—while the Keynesians plead—that no doubt money has a role to play—the importance of fiscal instruments of economic stabilization and demand management cannot be minimized. Perhaps, we can put this debate into somewhat better form if we keep in mind that neither fiscal nor monetary policies in isolation (or taking together) have yet proved adequate to cope with the serious and persistent problem of stagflation.

(iii) Coming to the next issue to basic stability of the demand function for money—which ultimately means the problem of the stability of the income—velocity of money (GNP/M1)Friedman has said that this does not mean that velocity of circulation of money has to be numerically constant over time—in his view the stability involved is in the functional relations between the quantity of money demanded and the variables that determine it.

In other words, it means not that the velocity cannot change, but that the changes are gradual and predictable. However, it is felt that this may have been the case at times in the past, but it has not been the situation in recent years especially during the 1980s. On the other hand, velocity—the rate at which money turns over or changes hands is declining and this has caused lot of trouble in the economic system.

The economists have not been able to in fact, could not make it out—that the Federal Reserve (of USA) is pumping out plenty of money (dollars) in 1980s but it is just not circulating. Some economists feel they have got to the truth. They feel that money’s velocity has declined, which in turn, causes’ the trouble. Velocity, as we know, is a simple measure of the rate at which money changes hands or turns over. This change in velocity signifies fundamental change in the way money is utilized and how fast the economy can grow.

The Federal Reserve Boards (USA) had been pumping out money at nearly a 13 per cent annual rate in 1986 in the USA, yet real output had grown only by 2.5 per cent. Inflation, meanwhile, had been fading fast in that year. It is, therefore, clear that money is just not an engine of growth that it once was. Fed Board (USA) Chairman Paul A. Volcker remarked that M1, the narrowly defined money supply “is not today a reliable measure” of future inflation or economic growth. He felt that it might take years to understand the new features of the velocity of M1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The danger, some economists warned, is that the Fed will create more and more money with less and less economic effect. Not that the extra money is falling into a black hole—it is simply not turning over as fast as it used to be to stimulate production or investment. Ultimately, the money could be trapped in the hands of the people who are supposed to spend it and we will be approaching something like ‘liquidity trap.’

Strictly speaking, economists define a liquidity trap as a condition in which no amount of money can push interest rate lower. People want to take all the cash that the central bank (Fed) pushes out and put it into their checking accounts instead of buying interest paying securities, such as bonds. As a result, the lack of demand for securities keeps rates unchanged. Economists have argued about this possibility (liquidity trap) ever since Keynes warned of the liquidity trap in the 1930s.

Clearly, that condition does not obtain today. Rates are still declining and people are still spending. But considering the amount of money which the Fed. in USA had pumped out in 1985-86, it is clear that something has gone haywire in the relationship between the money supply and interest rates.

What has happened? In the 1970s monetarist economists argued that money growth is closely linked to economic growth and that the velocity, growing at about a 3 per cent annual rate, was a stable part of the equation.

Since 1980, however, velocity has been bobbing, and it has fallen dramatically since 1985. Slower velocity means that each unit of money (dollar) is doing less work, so you need more units of money (dollars) to support a given level of economic activity. Most of the monetarists are interpreting these changes with care and caution and feel that they are “not convinced that there was anything lasting going on.”

Some monetarists believe that the velocity’s unexpected behaviour in recent years has to do with problems of definition or measurement. Simply speaking, M1 and the gross national product are not what they used to be arid because velocity equals GNP divided by M1, changes in the numerator and denominator can make a big difference.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, over the past few years M1 has been broadened to include interest-bearing NOW accounts. These accounts are building up fast, as the growth of M1 shows, yet they turn over less frequently than the money in regular checking accounts. So the money growth translates into fewer transactions, which in turn, translates into lower output. That, they say, is one possible explanation for the cooling of the velocity of money.

Another probable reason can be that though M1 is growing quickly and people are spending money as before; but now they buy more imported goods than before. This worsens the nation’ trade balance, which cuts into the GNP, shrinking the numerator in the velocity equation. So M1 divided s into GNP fewer times, yielding lower velocity. Then there is the case of missing transactions—not captured in the GNP statistics and thus not properly noted. All this liquidity, for instance, has certainly been put to use buying common stock and other financial assets.

The turnover is there—feels the monetarists— but it is not reflected in current output. Therefore, the problem of the stability of velocity is undergoing change and it is very difficult to say that it will remain stable under fast changing circumstances as claimed by the monetarists—whatever are the reasons. Many economists argue that the real rates of interest (the inflation-adjusted price of money) have not fallen nearly as fast as nominal rates of interest have.

The linkage between money growth and spending really works through the real rates of interest. It has been a very unusual situation for the Fed (in USA) to be stepping up money growth but holding real rates of interest high at the same time risking recessions at times. Velocity and its assumed stability in Friedman’s equation has been the greatest causality in the process and it appears the assumption of stability of velocity holds true no more—as assumption on which the entire monetarist edifice is built.

In essence, the evidence shows that the demand for money is fairly sensitive to the rate of interest, but not equally so sensitive as the earlier Keynesians had claimed.

(iv) As regards the central banks control of money supply—the evidence shows that over a long period the monetary authorities can control with reasonable accuracy the total money supply (M1) but they are less able to do so in the short-run.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Before concluding a few final comments may be attempted:

“Distinguished economists have said that Professor Friedman’s elaborate formulation of the modern quantity theory of money (monetarism) is really nothing more than an elegant and sophisticated statement of modern Keynesian monetary theory. Once the especial meaning that Friedman gives to wealth and costs of holding money are understood the basic similarities between his demand function for money and the Keynesian demand function for money relationship should be clear.

As a matter of fact, some of the monetarist advocates felt disturbed as they thought that Friedman’s effort to clarify the monetarists transmission mechanism inherent in the monetarist structure/theory only brought him closer to the Keynesian view of the process. Friedman was charged by some critics that he did not really understand the essential character of Keynesians’ analysis, especially the role that uncertainty plays in the Keynesian system.’

The differences between Friedman and the Keynesian approaches are more ideological than theoretical. This is probably true, because in a fundamental sense the monetarists counter revolution is an attack on the basic Keynesian idea that a market economy is inherently unstable and, if it is to work well, government may play a stabilizing role through its monetary and fiscal means.

A Reconciliation:

The neo-Keynesians or post-Keynesians, Walter Heller, Arthur Okun, Tobin, Samuelson, etc., do not take extreme positions and feel that both fiscal and monetary policies are important determinants of the level of real output. In the current state of the controversy, few economists can be labeled as being completely in the monetarist or fiscalist camps. The debate or the dispute between the two approaches is a sham dispute and the question of choosing one at the cost of ignoring the other does not, in fact need not arise ; because one (monetary policy) is extremely helpful in the long-run during inflation and the other (fiscal policy) is very helpful in the short-run during depression.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The neo- Keynesians argue that it is possible that changes in aggregate demand will cause changes in the demand for money which require the monetary authority to respond to the needs of trade and activity and so increase the supply of money. Thus, the crux of the argument between the Keynesians and monetarists is simply which theory best explains and predicts the actual behaviour of the GNP, prices and unemployment.

The post-Keynesian position is that it attempts to select the best from both the camps: post- Keynesians argue along with the fiscalists that the major impact of the monetary policy is transmitted to the real sector indirectly through changes in the interest rates of non-money financial assets. Post- Keynesians argue with the monetarists that money demand is interest inelastic. But they also argue that since money supply is positively related to interest rate and is relatively interest elastic, the combined interest elasticities of money supply and demand make the LM schedule interest elastic.

They also argue with the monetarists that real business investment is highly interest elastic, so that the IS schedule is highly interest elastic. Thus, with both highly interest elastic IS and LM schedules, the post- Keynesians conclude that both monetary and fiscal policies are viable and acceptable means whereby the economy can be controlled through aggregate demand management (money, no doubt, matters but fiscal policy also matters).

Despite, the position of post-Keynesians the debate still exists between monetarists and Keynesians. The nature of the debate is basically the same as that which existed in the past for many years over the use of Keynesian theory of the determination of the level of economic activity and the quantity theory of money as a theory of the determination of the level of economic activity.

Thus, we conclude that both monetarism, old monetarism, neo-monetarism and neo-monetarism— and Keynesianism—post-Keynesianism and neo-Keynesianism—are one-sided and partial. They are effective during a particular phase of the trade cycle in a capitalist economy, while monetarism is more effective during inflationary phase—Keynesianism is more effective during deflationary phase of the cycle.

Hence, a judicious mix of the two—more of monetarism and less of Keynesianism during inflation and more of Keynesianism and less of monetarism during deflation—may help economic growth with little stability in advanced capitalist economies. However, neither Keynesianism nor monetarism nor a mixture of the two is capable of initiating development process in developing countries—because these policies emphasise the regulation of supply of and demand for monetary factors—whereas the real problem in developing economies is the generation and regulation of supply and demand for real physical factors in a planned way.

One may agree with the observations made by Prof. P.R. Brahmananda that “Our judgement is that the analytical structure of Keynes and/or of Friedman are non-relevant under the Indian setting, primarily because both the above structures wholly reject Says law and glorify that investment or money has an independent influence on output through the channel of magnified real demand. Both the Keynesian multiplier and Friedmanian real velocity are non-starters. The figures given further show the working and policy implications of monetary and Fiscal Policy mix.

The Monetary—Fiscal Policy Mix:

It being evident that neither monetary policy nor fiscal policy acting alone can deliver the goods and desired goals. There being general agreement that one policy can be more effective than the other under particular situations—monetary policy is more effective in inflation and fiscal policy is more effective in deflation. However, from the practical viewpoint of policy formation, the decision taker will have to resort to both measures simultaneously.

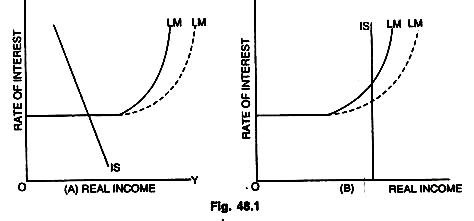

Here, it is shown that in order to determine the most appropriate policy mix for any given situation, a combination of fiscal and monetary policy is necessary to adopt. The combined impact of monetary and fiscal policy is shown diagrammatically with the help of well known Hicks-Hansen IS/LM curves. The conventional IS/LM portrayal carries an implicit bias against monetary policy because our original attempt was to popularize Keynesian economics through IS/LM curves. This bias against monetary policy is clear from the Fig. 48.1.

In the Fig. 48.1(A) a horizontal portion of the LM curve expressly assumes the Keynesian liquidity trap and shows that monetary policy is completely ineffective in influencing either the income level or the rate of interest (as indicated by the dotted line) if IS/LM intersection occurs in this region of the liquidity trap.

In the same manner, Fig. 48.1(B) shows a vertical IS curve which is derived from the assumption of a completely interest inelastic demand function and clearly shows that here again monetary policy is of no use, yet new approach stresses the fact that monetary changes will influence expenditure decision irrespective of the investment response.

In brief, the new monetarism implies that the IS curve and LM curve are interdependent in that a change in the money supply would affect expenditure decision directly. Again, IS/LM functions are a useful expositional device for working out the implications of combined monetary and fiscal policies and for classifying the alternative policy in a given situation.

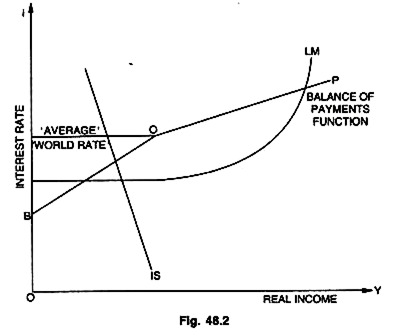

Moreover, the external sector can easily be taken into consideration in this analysis— as shown in Fig. 48.2. In this figure we superimpose a balance of payment function ‘BOP’ upon the standard IS/LM diagram. The BOP curve summarizes all the combinations of interest rates and income which maintain equilibrium in the external account.

This curve (BOP) has a positive slope, because if exports are assumed to be exogenous, an expansion of income will deteriorate the trading account (of BOPs) as increased income will lead to more inflow of imports. For the maintenance of equilibrium, therefore, a compensating improvement upon the capital account is required—this will come by raising of the interest rate.

A high interest rate will attract foreign capital in the country and this is likely to abolish the overall trade deficit in BOP. So to maintain equilibrium in the external account an expansion in income must be accompanied by an increase in interest rate—i.e., positive relationship—that is why it is said that BOP curve has a positive slope.

We see that the BOP curve is kinked at point ‘O’. In the diagram we assume that the responsiveness of capital inflows to a change in the rate of interest will depend crucially upon interest rates prevailing elsewhere (in other countries) in the world. If the rate of interest is below the average rate prevailing in the world (in other countries i.e., below point ‘O’ in the Fig. 48.2), it is hardly likely to induce substantial capital inflows whereas when it rises above the ‘world average’—the response will be much more immediate and significant.

At the same time we may reasonably assume that the ‘import’ effect of a given rise in income will approximately be the same regardless of whether increase occurs at a higher or lower level. That is why BOP curve is of kinked nature. The diagram is purely illustrative. We will now explain with the help of above figure, how a combination of both the monetary policy and fiscal policy are able to achieve external and internal balance. This is explained in Fig. 48.3.

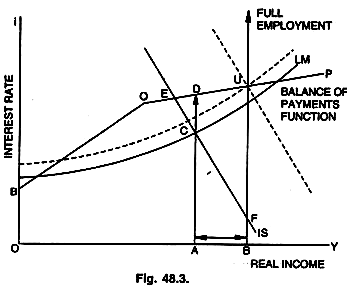

In the Fig. 48.3 we assume an initial situation determined by the intersection of the IS and LM curves at point (C). This intersection implies that the unemployment is equal to AB (on OY axis) and balance of payments deficit is equal FULL to CD. Now either monetary policy or fiscal policy acting independently is able to achieve one of the policy objectives.

If a contractionary monetary policy is adopted which means a rise in the rate of interest which will attract foreign capital in the country and thus cure the trading account of BOPs. In the Figure such a contractionary monetary policy will gain equilibrium at point E in the BOP curve curing the trade deficit (CD) in trading account. But it would not be able to attain full employment within the economy i.e., internal balance.

Hence, contractionary monetary policy will attain only external balance objective of removing the trade deficit—whilst an expansionary monetary policy i.e., a fall in the rate of interest (which will induce more investment) could take the economy to point F on the IS curve and meet the employment objective (thereby removing AB unemployment). Similar, reasoning applies to expansionary and contractionary fiscal policy.

But complete equilibrium i.e., both external and internal equilibrium at U (full employment deficit) indicated by the dotted lines can be attained by the combined interaction of both the policies simultaneously—namely an expansionary fiscal policy combined with a restrictive monetary policy; when a restrictive monetary policy is adopted—it will shift the LM curve to the left and an expansionary fiscal policy (increased expenditure) will shift the IS curve to the right and both (dotted curves) intersect each other at point U. Here at this point the dual objective {i.e. external balance and internal full employment) is achieved.

There is neither balance of payments deficit nor unemployment at point U. Both instruments (monetary and fiscal) are required to attain the dual objective. It may, however, be noted that both the required policy measures serve to raise the rate of interest. However, the possibility of an institutional interest rate limit prevents the adoption of the combined policy measure.

When institutional interest rate limit is there no possible solution is indicated other than successful devaluation (which effectively lowers the balance of payments function for any given income and interest rate (combination). Indeed, the very existence of unemployment and persistent external deficit would suggest over-valuation of the domestic currency.

Mundell Model:

Unemployment, low income, and related poor rates of growth are costly ways of achieving trade balance. Similarly, inflation, while it might indeed eliminate a trade surplus, is also rather a costly way of doing so. Governments aiming to eliminate unemployment and reduce inflation often see payments problems as an interference with their domestic plans.

However, both the objectives can be attained by a combination of both monetary and fiscal policies. The various conflicts in using fiscal and monetary policies to adjust national income and the balance of payments at the same time can be neatly shown first worked out by the two professors of international economics Trevor Swan and Robert Mundell.

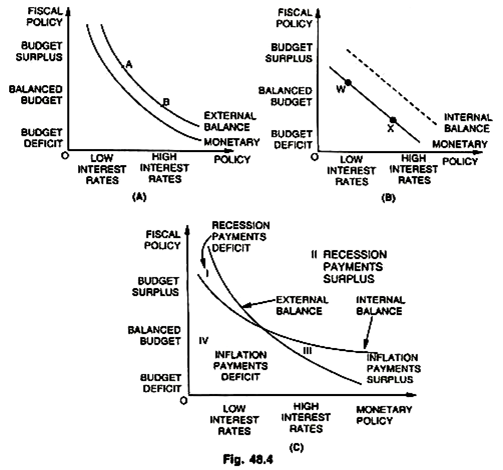

In the Fig. 48.4 fiscal policy is shown along the vertical axis with the government’s budget shown running upward from deficit to balance and then to surplus. Here, a budget deficit is presumed to be expansionary, balanced budget neutral and a surplus budget contractionary for the economy as well as for imports.

Interest rate is shown on horizontal axis which indicates the monetary policy. Low rates of interest are presumed to be expansionary for the economy as well as for imports and discourage the inflow of short-term foreign capital and hence deteriorate the balance of payments position. High rates of interest do the opposite.

In the Fig. 48.4(A), the curve shown is external balance curve which shows all the various combinations of fiscal and monetary policy that do not require any government intervention at a given exchange rate to support that rate.

In short, there is no deficit or surplus in the official settlements version of the balance of payments. Starting with the point A (which shows the BOPs equilibrium) on the external balance curve, we assume that the budget goes into deficit. Budget deficit results in an expanded economy, higher import and hence a balance of payments deficit.

Now to achieve payments equilibrium interest rates would have to be higher, as at point B on the curve. Higher rates (contractionary monetary policy) will discourage imports and at the same time attract short-term capital. Both effects tend to bring back the balance of payments equilibrium. The steep slope of the ‘external balance’ curve implies that the double impact of monetary policy on both trade and capital movements is relatively strong and that fiscal policy is relatively weaker where external balance is concerned.

Fig. 48.4(B) shows the curve for internal balance. This curve shows the various combinations of both fiscal and monetary policy that could bring about the best attainable level of low inflation and low unemployment. Here starting from W, we assume that government budget goes into deficit. This will expand the economy and be inflationary unless rate of interest rises and attains the equilibrium point X. The higher interest rates will have a cooling effect on the economy by controlling inflation (high interest rates control money in circulation) restore internal equilibrium.

In these diagrams, exchange rates are assumed to be fixed. If exchange rates alter, both the curves would shift, for instance, a currency (rupee) depreciation would encourage exports and discourage imports thereby improving the balance of payments. Now for any given government budget external balance will require lower interest rates which would stimulate the economy, raise imports and restrain the inflow of short-term capital. The external balance curve in Fig. 48.4(A) would shift leftward—to the dotted line and the shift would be large because of the effect on both trade and capital movements.

On the other hand, depreciation will shift the curve for internal balance upward and to the right, to the dotted line as shown in Fig. 48.4(B). Due to depreciation there will be more spending on our exports and imports will be discouraged and altered by the domestically produced substitutes. Now for internal balance to be non-inflationary, a greater budget surplus or smaller deficit would be required at any given rate.

To show what the policy alternations are and what their ramifications might be, the diagrams (A) and (B) can be/are divided into zones. In Fig. 48.4(A) external balance curve is shown that has a zone below and to the left of the curve where any combination of fiscal and monetary policy would result in a balance of payments deficit. Upward and to the right of the curve is a zone where the policy (A) combinations would result in a payment surplus.

The same technique is employed in Fig. 48.4(B) with internal balance curve. Here in the area below and to the left of the curve a combination of both the policies are inflationary while above and to the right of the curve they are deflationary.

Now, both the curves for external and internal balance are juxtaposed on the same diagram as shown in the diagram (C) which depicts the four distinct zones, each with a different mix of problems. In zone 1—both the policies produce recession and a balance of payments deficit. In zone 2—there is recession plus payments surplus. Zone 3—inflation and a payment surplus. In zone 4—there is inflation and payments deficit. Here, proper policy is easy to determine in zones 2 and 4 ; but involves conflicts in zones 1 and 3.

We take first zone 2. To counter the recession and to reduce the balance of payments surplus, both fiscal and monetary policies can be expansionary. Considering zone 4-there to cool inflation and to reduce the payments deficit contractionary fiscal and monetary policy inappropriate to adopt. But zone 1 calls for expansionary policy to curve the recession and contractionary policy to counter the payments deficit, while the opposite holds in zone 3, where contraction is necessary to counter the inflation and expansion for the payments surplus.

In selecting the proper policy in zones 1 and 3, the policy-makers will have to take note of the fact that the external balance curve is steeper than that for internal balance. From the slope of the curve (internal and external balance curves), it seems as if monetary policy has more powerful effect on external balance and fiscal policy on internal balance.

Thus, the policy-makers (or managers) will presumably prefer tight money and expansionary fiscal policy in zone 1 and easy money combined with budget deficit in zone 3. But a solution is not simple and the country located in either zone 2 or 4 has a much easier time deciding on its policy options. Thus, external and internal balance can be achieved with a judicious mix of both the policies. A single policy, acting independently, cannot achieve an overall balance or the desired objectives of full employment and trade balance.

Mundell’s model assumes that changes in the size of the budget surplus may be looked upon as an index of fiscal policy; while changes in the rate of interest are indicative of expansionary or contractionary monetary policy. Given the constraint of a fixed rate of exchange, appropriate stabilization policy requires that monetary policy be directed at external objectives and fiscal policy at internal goals. Moreover, failure to follow this policy prescription can cause discretionary stabilization policy to exert a perverse effect and render the resulting situation worse than the one it was designed to correct.

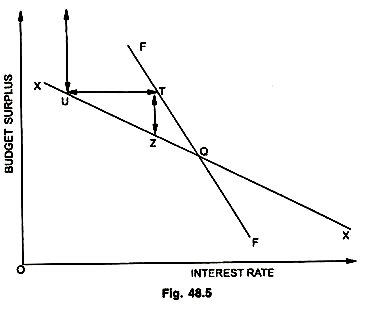

Mundell’s original diagram (Fig. 48.5) given here shows XX function—which describes all these combinations of budget surplus and interest rates which ensure full employment without inflation. The function has a negative slope since it is assumed that a decrease in the budget surplus, presumed expansionary, will require an offsetting cutback, in investment expenditure through higher interest rates, if the aggregate income level is to remain unchanged. Similarly, FF function summarizes all these budget surpluses—interest rate combinations which are consistent with balance of payments equilibria.

It is negatively sloped since with exports assumed constant any increase in imports arising from the expansionary impact of a lowering of the budget surplus must be compensated by an improvement in the capital account via an increase in the rate of interest.

The importance of Mundell’s Model lies in emphasizing the fact that efficient stabilization policy requires that policy instruments should be directed towards the policy objectives upon which they exert the most influence. Simply, to assert the required equality between instruments and targets is by itself an insufficient condition for effective policy-making. Even though the number of instruments may equal the number of declared objectives, the inappropriate use of the respective policy tools may be positively destabilizing.

Take point Z in the Fig. 48.5; being as XX function—such a combination of interest rate, and budget surplus is perfectly consistent with the employment objective but at the same time implies a deficit an external account. Should the authorities decide to correct it (deficit) by the use of fiscal policy, an increase in budgets surplus will restore equilibrium at point T; but will simultaneously produce a departure from full employment.

If monetary policy is now employed to restore internal equilibrium, it will require a decrease in the rate of interest to a position ‘U’; but such a move generates an increase in the external deficit over its initial level. Thus, the inappropriate pairing of the monetary and fiscal policy with the policy objectives is positively destabilizing in its impact. Thus, the repeated concern or debate with the comparative efficacy of monetary versus fiscal policy is really misplaced; what is required is a judicious and optimal policy mix to deal with any given situation.

Monetary-Fiscal Policy Mix and Growth:

Increasing attention is being paid in recent years towards the designing of suitable monetary and fiscal policy mixes to raise the rate of economic growth—aiming at raising investment rate at the expense of consumption.

It is argued that fiscal policy can be used to reduce consumptions; while monetary policy can be adopted to stimulate investment. The correct policy mix, therefore, is able to transfer resources effectively from current consumption to investment with beneficial effects on long- term growth rates.

The essence of Mundell model is that while there may be infinite number of budget surplus—interest rate combinations consistent with the maintenance of external balance; there will be but one unique combination able to satisfy both objectives simultaneously.

In other words, it follows that the force of external deficit cannot be ignored for long—likewise, there are strong political reasons limiting departures from full employment—the permissible monetary-fiscal policy mix for economic growth is effectively pre-determined as illustrated in the diagram here by dividing it in areas of high and low growth rates.

We find that the joint internal and external equilibrium conditions dictate the latter (low growth). The only way to achieve a high growth rate is through devaluation as shown by the inward shift of the external function (by dotted line). This need not surprise if we keep in mind the equality between the number of objectives and instruments.

The combined use of monetary and fiscal policy was able to secure dual objective of internal and external equilibrium, when used efficiently—the additional objective (economic growth) requires an additional policy tool—in this case exchange rate policy.’

In other words, the attack on problems of inflation, deflation, stagflation, BOP etc. has to be multi-pronged and the judicious mix has to be really judicious because the elements and the proportion in which these are combined in a judicious mix have to undergo a change depending on the circumstances prevailing in an economy and the stage of its development.