There are two main theories about the development of the terms of trade which have dominated the thought of economists during the last two centuries.

The British School:

The first kind of theory which deals with concerning the long-run development of terms of trade will be called the British school as it has been primarily the concern of British school.

The beginnings of the British school date back to the English classical economists. One of the firm beliefs of the classical economists was that of the decreasing returns of agriculture.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This belief was one of the cornerstones upon which Ricardo built up his theory of income distribution. Because of the decreasing returns to scale in agriculture, the income distribution would move in favour of the landlords; population would increase and keep the wage at a subsistence level the capitalists would be squeezed, and the landlords would reap an increasing land rent and live forever in leisure at the expense of others.

Thus, as the size of the population expands and the demand for food grains increase rent as a share of national income goes on increasing, wages cannot be reduced below the subsistence level and profit goes on decreasing. In 1821, Robert Torrens pointed out that the decreasing returns to scale in agriculture would have ominous consequences for England’s terms of trade. Torrens believed that the terms of trade would go against the industrial countries including England.

The price of manufactured goods in terms of food products and raw materials would steadily decrease, and the developed industrial nations which exported manufactured goods would suffer from this development until finally the volume of trade would diminish to such an extent that every country would be self contained.

Although this theory is primitive yet in its own way it is complete and quite logical. Its most crippling defect is its failure to take into account technical progress. If one is willing to disregard technical progress and to assume that there are constant returns to scale in the production of manufacturers but decreasing returns to scale in agriculture, Torren’s result is quite likely to occur. Its chief fault lies not in defective, deductive, reasoning but in the narrow and unrealistic assumptions upon which the analysis is built.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The line of thought that Torrens inaugurated was virtually upheld by English economists during all of the 19th century; and its remnants can be seen to this day. Its chief proponent during the 20th century was no one else but John Maynard Keynes. In 1921 Keynes wrote in the Economic Journal that the deterioration of Britain’s terms of trade during the first decade of the 20th century was due to the operation of the law of diminishing returns and the comparative advantage was moving sharply against industrial countries. Thus, Keynes adhered to the old, classical tradition.

In his, book, the Economic Consequences of the Peace, published in 1920, Keynes reiterated his belief in the inevitability of deteriorating terms trade for industrial countries. The fear of a long-run deterioration of the terms of trade, which would cause foreign trade to be of little advantage to Europe including Britain and would jeopardize its future economic progress, haunted his mind. The main criticism that has been raised against the British school is that it tends to oversimplify matters. The stress on one or two factors at the expense of others made the outlook of the British school narrow and rigid.

Singer, Prebisch and the Terms of Trade:

Named after Argentine economist Raul Prebisch (1901-1986) and German born British economist Mans Singer (1910), Prebisch-Singer thesis asserts that, given the permanent tendency for the terms of trade to go against agricultural products, it is in the interest of developing countries to erect protective tariffs behind which they can industrialize.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The structure of the Singer-Prebisch theory of development and trade is much more complicated. The theory takes into account the influence of the business cycle on the terms of trade, the interrelation between factor rewards and the terms of trade, the effects of different market forms on the terms of trade, and so on. These different hypothesis are neither clearly expressed nor rigorously formulated.

The Singer-Prebisch case starts as an explanation of the hardships of South American economies and as a rationalization for certain policy conclusions. In “Commercial policy in the Underdeveloped Countries”, Raul Prebisch begins by saying that the only way for South America to speed up its rate of economic growth is by attempting Industrialization. If the South American countries try to increase their primary production, their supply of raw materials and food products, they will meet falling terms of trade, because their income and demand elasticities facing them in their export markets are very low. But these countries need rising export incomes in the development process because their own marginal propensities to import are very high.

If the income elasticity facing the exports of the underdeveloped or peripheral countries is low and if the demand and supply are inelastic with regard to price, little is to be gained from pushing these exports. However high the domestic growth rate within the export industry may he, most of the productivity gains within the export sector will be exported away through falling terms of trade. This is the core of Singer- Prebisch thesis. But there are other theories or propositions attendant lo it. Let us discuss these related propositions.

One of Prebisch’s arguments is concerned with the effect of business cycles on the terms of trade. In boom times, profits, wages and prices rise. But profits rise more than wages and prices in the peripheral countries rise more than pries in the industrial countries, so profits among primary producers ri.se even more than profits in the industrial countries. On the downswing however, profits, wages and prices now ought to fall but because of the downward rigidity of wages there, they will not fall in industrial countries. Profits in the center (industrial countries) will be squeezed, and entrepreneurs in these countries restore their profits from the periphery.

The workers in the primary producing countries do not have strong organisations, and consequently wages and profits are squeezed more in these countries to ensure that profits in the center are kept at a level which is not regarded as abnormally low. It is hardly possible to analyze this line of argument closely. Prebish does not explain why prices in the peripheries decrease relatively more in the downsizing than they improve in the upswing, so that the end result is a deterioration in the terms of trade of these countries.

One part of Singer-Prebisch thesis which has attracted both more attention and more support is theory about market forms and the terms of trade. Prebisch points out that while in industrial countries monopolistic market forms are common, the export-industries in most less developed countries work under competitive conditions. Would monopolistic market conditions tend in the long run to improve the terms of trade for a country and would free competition tend to worsen them?

Many economists seem to take for granted that monopoly gets better terms of trade than competition for a country. The rate of technological progress tends to be higher under the monopolistic market conditions than under competition. Output in the long-run will expand and the growth rate of supply will be higher under monopolistic and oligopolistic conditions than under free competition. Only those firms that operate on a large scale can afford the research and development needed to introduce cost reductions and new products.

The implications of these arguments are clearly contrary to the hypotheses of Prebisch. The more monopolistic and oligopolistic market forms a country has in its export sector, the worse the prospects are for the terms of trade, a result which is opposite to Frebisch’s assertions. These are complicated matters, and Prebisch’s slightly extravagant assertions do not stand up too well under closer scrutiny.

Another explanation for the deterioration in the terms of trade of the underdeveloped countries lies, according to Singer and Prebisch, in the fact that the industrial countries have much stronger labour organisations than the peripheral countries. In the absence of labour unions, wages can be depressed, which leads to falling product prices and deteriorating terms of trade. This argument seems to have certain plausibility. The difficulties with institutional arguments of this sort are that they are hard to fit into a consistent theory.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The chief difficulty one encounters in analyzing the Singer-Prebisch approach to growth and trade is its looseness. If we take the Singer- Prebisch case in its simplest variant, that is, as a simple statement that the terms of trade will go against the less developed countries, it is not difficult to make a highly plausible case for it. But the economists of this school are not satisfied with just that. They want also to give very special and intricate explanations for the deterioration of the terms of trade of the peripheral countries.

There is no need to fall back upon highly dubious theories about the influence of market forms, of labour unions etc. Simpler reasons, can be given for why the terms of trade might go against the less developed countries and why growth through trade might prove a fruitless venture for these countries. If we consider this the core of the Singer-Prebisch case there are three conditions necessary for reaching their conclusions.

These are that growth must be confined to the export sector, that the degree of adaptability must be low (so that the value of the respective demand and supply elasticities will be small), and that the demand for the country’s export products must only now slowly. Usually the first two conditions, the export biased growth and the low adaptability are taken for granted, if only implicitly. Then the decisive circumstance is the growth of demand. If this is sluggish the Singer-Prebisch result will follow. This is the critical condition without which no valid version of the Singer Prebisch case can be constructed.

It might now be useful to construct a few examples which will lead lo results along the Singer-Prebisch lines. We can apply the two country model and think it terms of one less developed agricultural country and one developed industrial country. Let us start by thinking In terms of the model of unspecified growth. For instance, if the Income elasticity facing the less developed country is only one third of that facing the industrial country, and if the export sector is large in both countries, then the overall growth rate of the less developed country can be roughly only one third of that in the industrial country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If it is higher, the agricultural country will get deteriorating terms of trade. With export biased growth in both countries, the factors of the greatest importance for the growth of real national income are the size of the export sector and the value for the income elasticities. The larger the export share in the agricultural (peripheral) country, and the lower the Income elasticity of importable in the industrial country, the more the terms of trade will go against the peripheral country and the less its real income will grow. How much the terms of trade will deteriorate given these conditions, depends primarily on the demand and supply elasticities.

The possibilities of growth of the less developed country to a large extent, is determined by the development of the rich country. The faster the growth of the industrial country, the greater the possibility for growth without impediments to the agricultural country.

The effects of an increase in labour or capital on the terms of trade depended on factor intensities. Many underdeveloped countries have a rapidly growing labour force. Such a country is abundantly endowed with labour, so it is expected to export labour intensive goods. If this is the case, an increase in the labour force will lead to deterioration in the country’s terms of trade. Again, much will depend on the country’s elasticity of demand for imports. If this is high, it will have a negative effect on the terms of trade, because it implies that as the country grows, more and more of its demand will be directed toward imported goods.

This is a situation in which many less developed countries find themselves, because they need to import capital goods to get their development process underway. Export biased growth where the source of growth is an increase in the factor endowments will always increase the volume of exports and will lead to an increased dependence on foreign trade. The effects on the real national income will depend on the behaviour of the terms of trade. If the negative influences on the terms of trade are strong, most of the prospective gains of growth will be exported away.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally let us see what the effects will be if technical progress is the source of growth. The effects of technical progress depend to a large extent on which sector it occurs in. Singer and Frebisch focus their attention on the export sector; if this is the leading sector, the only “modern” sector in the economy, it is natural to regard it as being the one where innovations occur. Most innovations in the export sector will have negative effects on the terms of trade.

We know that for the most general case, the one where production functions are unspecified, three strategic factors determine the upshot for the terms of trade: the un-ward shift in the production function associated with technical progress, the way the marginal productivity of labour changes and the way the marginal productivity of capital changes because of the innovation.

The first effect will always have a negative influence on the terms of trade. So will the other two under normal circumstances (provided, that is, that the marginal productivities increase because of innovation). Therefore, we would expect the terms of trade of deteriorate because of technical progress in the export sector.

How much they will deteriorate depends on several more factors. The more the marginal productivities increase because of the improved technique, and the more the production function is lifted by the innovation, the more the terms of trade deteriorate. The larger the income elasticity of imports and the smaller the value of the elasticity factor, the less hopeful are the prospects for the terms of trade.

A rapid growth of the export sector, combined with a high marginal propensity to consume importable and a low degree of response on the supply and demand side in both countries to changes in relative prices, make a rapid deterioration of the terms of trade. Now the real national income is affected by technical progress depends to a large extent on the course of the terms of trade. If the terms of trade deteriorate heavily for the progressing country, the increments to the real income will be small. This will be the case specifically if the country has a large export share.

The above discussion substantiates the Singer-Prebisch thesis in its basic version and to show that under quite realistic conditions the terms of trade can move against a less developed country and make growth along established lines a very frustrating undertaking.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Concepts of Terms of Trade:

Since the Second World War, there has been great interest in the terms of trade, especially on the part of countries whose foreign trade is large relative to income and output. For such countries changes in the terms of trade may have a major impact upon the level of income. Another reason for the wide spread interest is the possible role the terms of trade may play in explaining changes in Income differentials among countries.

Changes in the terms of trade may affect the international distribution of income and there is particular interest in whether or not unfavorable terms of trade may provide some explanation for the low levels of income in many countries. Furthermore, some economic historians consider the terms of trade to be an important variable in explaining the course of economic history. The behaviour of terms of trade plays an important role in many problems of economic policy today.

There are several different measures of the terms of trade, each representing a different concept. The different measures are the net barter, gross barter, income, single factorial and double factorial terms of trade. The most widely used is the net barter terms of trade or also called the commodity or merchandise terms of trade. The commodity terms of trade is simply an index of export prices dividend by an index of import prices, with the quotient expressed as a percentage [(PX/PM)x100)

A rise in the net barter index overtime means that a given volume of exports will exchange for a large volume of imports than formerly. But the index does not indicate what has happened to the physical volume of commodities traded. Only if the values of exports and imports were equal in the base year and the year under study, would an improvement in the net barter terms of trade mean that country actually obtained more imports with a given volume of exports.

Changes in the physical volume of exports, and imports are apt to accompany changes in the ratios of export prices to import prices. Two of the other concepts embody volume changes. The gross barter terms of trade is the index of the quantity of exports divided by the index of quantity of imports [QX/QM x100].

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The resulting index represents the rate of exchange between the aggregate physical exports and imports of a country. The meanings of changes in this measure are ambiguous whenever the value of exports and the value of imports are not equal. For instance, a fall in the Index suggests an improved position because a given quantity of exports exchanges for a larger quantity of imports. But the change may be due entirely to a transfer receipt or a capital inflow.

The favourableness or unfavourableness depends upon the type of transaction that changes the index. This index has not been very useful in analytical work because analysts generally have preferred to work directly with the causes of changes in the quantities rather than indirectly through the gross barter terms of trade.

The other concept that uses a quantity index is the income terms of trade (Q.S. Dorrance). It consists of the index of the value of exports (a quantity index times a price index) divided by the index of import prices. The index is actually the net barter terms of trade times the index of the quantity of exports [Px/PM]x Qx]

A rise in the index means that a country can obtain a larger quantity of imports from its sale of exports in a given year relative to the base year. Although frequently called a measure of the capacity to import, the index does not reflect the total capacity to import because the capacity depends upon the net capital inflows and net receipts from the invisibles in the current account as well as from commodity exports.

The three concepts discussed so far relate to the exchange between import and export commodities. The two other concepts the single and double factoral terms of trade relate to the exchange of productive factors embodied in traded goods. The single factoral terms of trade consist of the net barter index adjusted for productivity changes in the production of exports. The double factoral terms of trade entails the adjustment for productivity changes in both exports and imports.

The adjustment for productivity changes actually involves the calculation of the prices of factors embodied in the traded goods. For example, if the export price index falls 10 per cent while the productivity index for exports rises 20 per cent (both relative to 100 for the base year) the price of factors embodied in exports has actually risen to 108 [ (90×120/100)]

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If further the index of import prices remains at 100, the single factoral terms of trade are 108, an improvement despite the decline in the net barter terms of trade from 100 to 90. The rise in the single factoral index means that the country receives more imported goods per unit of productive factors incorporated in exports as compared with the base year. If the productivity for imports had risen to 1 10 in the example and if the import price index still remained constant, the double factoral terms of trade would have declined from 100 to 98.2[{90×120)/100×110}x 100= 108/110 x 100=98.2]

This index shows the change in the rate of exchange between a unit of domestic productive factors used in producing imports. The factoral terms of trade are not operational because of the impossibility of defining and measuring a unit of productive factor units and hence of calculating a meaningful productivity index. A simple index of labour productivity is not a satisfactory measure of productivity changes for all inputs.

The temptation is strong to equate changes in a country’s terms of trade with changes in its welfare or in its gains from trade. But the production of the welfare effects of changes in the terms of trade is not simple and direct. It depends upon the particular circumstances upon the underlying forces that cause any given change in the terms of side.

An adverse change in a country’s net barter terms of trade suggests that the country is worse off than in the base year because it has to export more goods to pay for given quantity of imports. The country will indeed be worse off if the adverse change results from a decline in the foreign demand, for its exports, all other things remaining unchanged.

If, by contrast, the decline in export prices results from the technological change that lowers production costs, and if the decline in costs is more than proportionate to the decline in the terms of trade, the country will be better off because it obtains more imports per unit of productive factors employed in producing exports than it did in the base year.

In this case, the net barter terms of trade deteriorate while the single factoral terms of trade improve; but the single factoral index correctly indicates an improvement in welfare. If the double factoral terms deteriorate, welfare in the foreign country or countries increases. Also it might increase more assuming someway of comparing welfare gains among countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The income terms of trade do not reliably indicate welfare changes. Assume that import prices and quantities remain unchanged and that exports and imports are equal in value in both the base year and current year. If export prices, rise, the country is better off in welfare terms because it obtains it’s given volume of imports with ii smaller volume of exports as compared with the base year ; that is, it’s real national Income is larger. The income terms of change arc- unchanged, however, so they do not reflect the welfare gains.

A country’s income terms of trade might important the same time that its net barter terms of trade deteriorate. Mm of exports could increase sufficiently to cause a rise in the index for income terms of trade. For a developing country, the capacity to import can be very important to Its development programme and its welfare might Improve overtime despite an adverse movement of net barter terms provided the capacity to import increases.

In the short-run, changes in the terms of trade may result from numerous causes, among which are demand shifts, changes in commercial policy, depreciation and transfers. In the long run, changes in the terms of trade result from structural shifts in demand and supply associated with economic development and growth.

Gains from trade: The Maximization of Real Income:

In the comparative cost approach to the problem of gain from foreign trade, the stress is put on the possibility of minimizing the aggregate real cost at which a given amount of real income can be obtained of those commodities which can be produced at home only at high comparative costs are procured through import, in exchange for exports, instead of being produced at home.

Ricardo and Malthus, In the course of a discussion of concrete problems of trade policy, offered some indication of the nature of the “welfare” presuppositions of their gain analysis. Malthus attributed to Ricardo the position that the saving in the cost under free trade resulting from obtaining the imported commodities in exchange for exports instead of domestic production not only demonstrated the existence of gains from trade but measured the extent of the gain.

To this proposition Malthus objected that the excess in the cost of domestic production of imported commodities over the cost of obtaining them In exchange for exports provided a grossly exaggerated measure of the gain from trade where the imported commodities could not be produced at home at all or could be produced only at extremely high costs.

Ricardo always views foreign trade in the light of means of obtaining cheaper commodities. But this is only, according to Viner, looking to one half of its advantages and not the larger half. This part of the trade is comparatively considerable.

According to Viner, “The great mass of our imports consists of articles as to which there can be no kind of question about their comparative cheapness, as raised abroad or at home. If we could not import from foreign countries our silk, cotton and indigo with many other articles peculiar to foreign climates, it is quite certain that we should not have them at all.

To estimate the advantage derived from their importation by their cheapness compared with the quantity of labour and capital which they would have cost if we had attempted to raise them at home, would be perfectly preposterous, in reality no such attempt would have been thought of.

Malthus held that the gains from trade consisted of “the increased value which results from exchanging what is wanted less for what is wanted more”; foreign trade “by giving us commodities much better suited to our wants and tastes than those which had been sent away, had decidedly increased the exchangeable value of our possessions, our means of enjoyment and our wealth.”

Malthus, here as elsewhere, meant by “value” or “exchangeable value” not value in terms of money but purchasing power over labour or “labour command.”

Ricardo, however, did not measure gain by changes in “value” as defined by him, and therefore did not deny that foreign trade resulted in gain. After laying down his proposition that foreign trade will not immediately increase the amount of value in a country, Kicardo went on to say that

“It will very powerfully contribute to increase the mass of commodities, and therefore, the sum of enjoyments.”

Kicardo suggests two income tests of the existence, and also two income measures of the extent of gain from trade, namely, an increase in the “mass of commodities” and an increa.se in the “sum of enjoyments.”

Both types of tastes involve in their application serious logical or practical difficulties.

Free trade necessarily makes available to the community as a whole a greater physical real income in the form of more of all commodities.

From the time of Ricardo on, the commodity terms of trade have been widely accepted as an index of the trend of gain from trade. Some economists have also derived a measure of the ratio in which the gains from trade were divided between two trading areas from their commodity terms of trade taken in relation to the comparative costs of production of the two areas.

John Stuart Mill’s analysis of the relationship between reciprocal demand and the commodity terms of trade was a pioneer achievement and constitutes his major claim to originality in economics the problem for which Mill seeks an answer is the mode of determination of the commodity terms of trade, lie first simplified the problem by assuming only two countries and only two commodities Mill said that the equilibrium terms of trade must be within the upper and lower limits set by the ratios in the respective countries of the costs at which the two commodities could be produced at home, but that the exact location of the terms of trade would be determined by the demands of the two countries for each other’s products in terms of their own products, or the “reciprocal demands”.

Equilibrium would be established at the ratio of exchange between the two commodities at which the quantities demanded by each country of the commodities which it imports from the other should be exactly sufficient to pay for one another, a rule which Mill labels the “equation of international demand” or “law of international values”.

Shadwell later objected that Mill had not really solved the problem by his “equation” or “law”, but had merely stated the truism that “the ratio of exchange is such that the exports pay for the imports”. Graham makes substantially the same criticism.

Bastable pointed out in reply to Shadwell, “Mill’s theory does not consist merely in the statement of the equation of reciprocal demand, but also in the indication of the forces which are in operation to produce that equation.”

According to Mill, the terms of trade are determined by the reciprocal demands.

Terms of trade and the amount of gain from trade:

From the beginning of the classical period, the trend of the commodity terms of trade has been accepted as an index of the direction of change of the amount of gain from trade. A rise in exports prices relative to import prices represents a “favourable” movement of the terms of trade. It has been recognized at times that the proposition is valid subject only to important qualifications.

Ricardo had little to say of the terms of trade as related to the gains from trade. Although J.S. Mill laid much greater emphasis than did Ricardo on the connection between the terms of trade and the amount of gain from trade, he also did not accept a favourable movement of the commodity terms of trade as necessarily indicating a favourable movement of the amount of gain from trade. Thus while he conceded that the imposition of protective important duties operated to change in a favourable direction the terms on which the remaining imports were obtained, he claimed that this advantage was more than offset by the loss of the benefit which had previously accrued from the trade in the commodities now produced at home under tariff protection.

Similarly, when he showed that a reduction in the real cost of production of Germany’s export products would operate turn the terms of trade against Germany, he refrained from drawing the conclusion there from that the reduction in the cost would be injurious to Germany even in the least favourable case where the commodity whose cost of production had been reduced was not consumed at all within Germany itself.

Marshall and Edgeworth both adopted changes in “consumer’s surplus” or its supposed equivalent, as a better index of change in the amount of gain from foreign trade. The general position of the major writers in this field was that an increase in the amount of imports obtained per unit of exports was presumptive evidence of an increase in the amount of gain from trade, but that the validity of the presumption was subject to the absence of countervailing factors.

As examples of such countervailing factors, Marshall took account of increases in the cost of the export commodities and Taussig referred to a decrease in the desire for the import commodities. Jevons criticized Mill’s use of the commodity terms of trade as measure of gains from trade on the ground that the total amount of gain from trade depended on total utility, whereas the commodity terms of trade were related to “final degree of utility”;

“in estimating the benefit a consumer derives from a commodity it is the total utility which must be taken as the measure not the final degree of utility on which the terms of exchange depend.” In utility terms, the total amount of gain from trade can be defined as the excess of totally utility accusing from the imports over the total sacrifice of utility involved in the surrender of the exports.

The commodity terms of trade will always equal the ratio of the marginal disutility of surrendering exports to the marginal utility of imports. Disturbances will change the terms of this ratio, but not the ratio itself. The marginal unit of trade, therefore, will never, under equilibrium conditions, yield any gain, and whether or not a “favourable” movement of the commodity terms of trade will represent an increase in net total utility will depend on what, if any, change occur.

(i) In the utility function of import,

(ii) In the disutility function of export,

(iii) In the volume of trade.

Reasoning such as this was presumably the basis of Jevon’s comment.

Barone’s Graphical Technique:

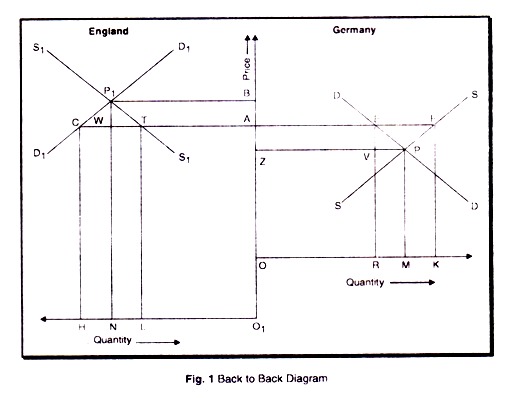

Cunynghame, in 1904 expounded the theory of international value with the aid of a type of graphical illustration related to the ordinary Marshallian domestic trade demand and supply diagrams in terms of money prices and derivable from them. In Cunynghame’s diagram, as in Marshall’s domestic trade diagrams, only one commodity at a time is under consideration and the diagrams relating to the two regions are set back to back for purposes of comparison and analysis. Cunynghame did not draw any conclusion with respect to gain from trade from his diagrams, but Barone, in 1908, used the Cunyghame back to back diagram to reach such conclusions.

The figure 1 is a reproduction of Barone’s basic diagram. The demand and supply curves of the particular commodity under consideration expressed in terms of money in a currency common to both countries, are given separately for each country, with the two diagrams set back to back. In the absence of international trade in this commodity, its price would be P1N in England and PM in Germany. If trade is opened, England will therefore be the importer of the commodity and Germany the exporter.

The cost of transportation per unit is assumed to be OO1 and after trade, therefore, the price in England must be the price in Germany plus OO1. Equilibrium will be established at the price, f.o.b. Germany, at which the quantity England would import, CT, is equal to the quantity Germany would export, 1:1″. The price, therefore, will be RE in Germany and HC ( RE + OO1) in England.

Barrone says each country will gain as the result of the trade. In England, the gain to consumers will be P’CAB monetary units, which is greater than the loss to producers, P’TAB. In Germany the gain to producers will be AZPF, which is greater than the loss to consumers AZPE.

Barrone’s reasoning has been criticized in many counts. First, it ignores the effect which the removal of barriers to trade would have on gold movements and therefore on the heights of the demand and supply schedules and the prices in the two countries. Second, the area CP|W included by Barrone in the gain to English consumers is not homogenous with the area BP1WA, the latter being an actual saving in money, whereas the former is a “consumer’s surplus” of indefinable meaning as compared to the area BP1WA. A similar objection applies to the inclusion of the one EVP in the loss accruing to German consumers.

These areas are akin to a portion of Marshall’s consumer’s surpluses in his domestic trade theory, and are subject to the same criticisms. Third, the calculation of gain or loss to producers from changes in price and output assumes that the ‘producer’s rent’ areas represent net real income to producers without involving real costs lo anyone else in the community, an assumption inconsistent with normal reality in the one respect or in the other or partly in both.