In this article we will discuss about Business Firms:- 1. Objective of a Business Firm 2. Indicators of a Business Firm.

Objective of a Business Firm:

Whatever may be the overall objective of a firm it is necessary to break it down into constituent parts to form the objectives or the targets of the relevant constituent units, groups, sections or departments of the firm. Although the overall general objective is expressed vaguely, it is essential to express the targets in concrete and measurable (quantifiable) terms.

An important function of modern management is the appraisal, at periodic and regular intervals, say quarterly or monthly or even weekly, of the degree of achievement of the targets at the micro-level, i.e., at the level of a section or department of the firm.

Such appraisal is facilitated by the quantitative terms in which targets are set or budgets are laid down. A firm’s accounting systems provide necessary information which can be fruitfully utilized for numerically measuring or quantifying the performance of the firm as a whole.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A considerable degree of precision can be reached regarding such appraisal depending on how such information is used in relation to the firm’s objectives and how those objectives are translated into targets for the next accounting year. Inasmuch as profit is almost always an element in basic objectives, the absolute amount of profit made in a year is a primary indicator of its performance. There is a twofold reason for this.

The primary reason seems to be that “a given profit target may in the first place simply have been what the firm thought it could achieve, having regard to the last year’s profit, adjusted upwards or downwards according to the firm’s expectations of changes in the demand for its products and changes in other commercial conditions.”

Secondly, a given absolute amount of profit carries significance only in relation to capital employed by the firm. It makes a lot of difference between earning a given amount of profit by using a small as opposed to a large amount of capital.

In fact, a very important business (or managerial control) ratio is arrived at by setting profit against capital employed. However, this is not the only ratio which throws light on the performance of the company. There are various other ratios as well which can be fruitfully utilized to assess the position and performance of a firm. All those ratios are not of equal importance to management and some of them are of no interest to it.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, some of these are of greatest use and interest to the management, some to its shareholders and some to its creditors, actual or potential. We may now bring into focus some of these ratios to test the performance of a firm and its position in the industry to which is belongs.

Indicators of a Business Firm:

I. Profitability:

As a general rule, the efficiency with which a firm uses its assets is a primary indicator of its performance. The ratio which measures this is the rate of return on capital employed, or

Here the figure of profit is before tax profit. The object is to avoid fluctuation of the ratio for reasons of taxation. Interest paid on money borrowed is added back into the profit figure so that profitability of capital is not affected by the alternative methods of financing investment (capital expenditure).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here capital employed equals the difference between total assets (fixed and current) and current liabilities (which include obligations to pay debts incurred in the day-to-day running of the business, such as in trade and to other creditors, and tax and dividends payable).

The ratio is extremely useful to firms not only for comparing their own performance over time but also for comparing their profitability with that of their competitors.

A certain portion of a company’s profit is taxed away. A portion of after-tax profit (i.e., net profit after tax) is distributed among the shareholders in the form of dividends. The amount of dividend that is distributed among the shareholders depends on the actual performance of the company.

A portion, which is not thus distributed, is retained and ploughed back for growth and diversification. The shareholders are also interested in the amount that is retained in the company because it serves to increase shareholders’ funds, or to provide long- term ‘funds for company growth.

In fact, the value of their shares and future dividends vary directly with the amount of earning which is retained (i.e., undistributed net profit after tax).

However, the shareholders relate profit not only to capital employed, but also to the company’s equity. It is because all of them have a share in the equity. The shareholders are the owners of the company and the equity is the owners’ fund as opposed to debt capital (borrowed fund). It is acquired by issuing ordinary shares. The reserves and undistributed profit are also part of the shareholders’ funds.

Since dividends are declared after paying tax out of net profit, the shareholders are more interested in after tax rather than before tax profit. This figure is arrived at without adding back interest paid on borrowings. It is because it is only this net amount which is available to them.

This explains why the shareholders are primarily interested in the following profitability ratio:

The shareholders are also interested in the yield, i.e., the ratio of dividends per share to that share’s market price. However, since the capital market at a particular time under or over-values a share, an actual or potential shareholder may be desirous of considering both ratios. A shareholder may also consider the firm’s total earnings per share.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A key indicator of business performance is the rate of return on capital employed.

This key ratio shows the interaction of two further ratios:

(a) The profit margin or sales, or mark-up, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) The total value of sales in relation to capital.

Thus:

and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since capital is employed to achieve a sales goal, actual sales are the end result of the employment of capital. The rate of return on capital employed is the result of movement in either of these two ratios. What is of strategic significance to a modern business enterprise is that movements in both may well reinforce each other. This may be either beneficial or harmful for the company.

Alternatively, these two ratios may neutralize each other, depending on the direction in which they move. Companies often have to exercise a realistic choice of policy as to whether to go for a low profit margin on sales, supported by a high sales turnover in relation to capital, or a high margin of profit coupled with low turnover.

It may be added that “scrutiny by management of these two ratios assists in identifying directions in which efficiency, and therefore the rate of return, may be improved.”

The total sales turnover (or total revenue) in relation to capital employed measures the rate of capital turnover or the velocity of its circulation, i.e., the frequency or rate with which capital assets are turned into sales. This is an index of the efficiency with which capital is employed in an enterprise.

There are various ways of improving a company’s operational efficiency. The easiest way seems to be to economize on capital, especially when there is not much scope of increasing sales turnover. On the contrary, if a company grows by employing more and more capital it is absolutely essential to ensure that sales rise proportionately so that the turnover ratio is maintained.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

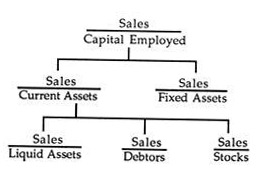

Otherwise this ratio will fall and a paradoxical situation will be encountered — growth will be accompanied by lower profitability. An in-depth analysis of this ratio is possible if we break down the sales to capital ratio, into the underlying ratios of sales to particular kinds of asset as the following chart shows.

Performance ratios relating to profitability carry enormous good sense in normal times when there is neither war nor abnormal inflation (or deflation). However, in an age of uncertainty, a term coined by J. K. Galbraith, such ratios can be really misleading if there has been a change in the general price level.

These two are probably the most important managerial control ratios. It is because close scrutiny by management of these two ratios assists in identifying directions in which there is scope for improving efficiency and therefore the rate of return.

Due to stock appreciation and rise in the market price of fixed assets keeping a firm’s accounts at the traditional historical cost has largely, if not entirely, lost its relevance. There will be stock appreciation during inflation. But once the stocks are exhausted they are to be replaced at the new higher price level. So due allowance has to be made for this in calculating profit for the period under consideration.

Otherwise profit will be overstated to the extent of the appreciation of the stocks held at the beginning of the year and used in the production (as in the case of raw materials) and sale of output (as in the case of finished goods) during the year. The same type of treatment has to be made with respect to fixed assets which dole out their services over a long period of time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus the annual depreciation provisions made on the basis of their original cost will, at the end of the productive life of the asset, be grossly inadequate to replace it. Likewise profits over this period of years will have been overstated accordingly.

Inflation accounting technique has been introduced to deal with these problems. After much debate and controversy over the desirability of this technique the accounting profession in Britain reached the consensus that from 1980, ‘current cost accounting’ would be adopted for all companies with a stock exchange listing particularly the large firms.

II. Financial Stability:

i. Liquidity:

A company may be performing very well and its profitability ratio may be quite satisfactory. But its liquidity position may be bad in the sense that it does not have sufficient money in bank and cash in hand to oblige the creditors, i.e., repay its debt. This demands that a company’s entire investment should not be in fixed assets. Instead a proportion of assets has to be sufficiently liquid.

The term ‘liquidity’ was introduced by J. M. Keynes in 1936. It is a property which is enjoyed by all assets to some extent. It refers to the ease with which an asset can be turned into cash (without any loss or transaction cost). Some assets automatically do so on a maturity date, as when a bond is en-cashed.

Liquid assets are required to ensure that the firm can continue its operations by paying wages and salaries, paying suppliers of raw materials and continuing to be supplied with materials and services on credit. A liquidity crisis may even force a profitable enterprise to cease its operations. Thus a company’s liquidity is a matter of concern to its employees, creditors and shareholders.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By contrast, a company may well continue in business even by incurring losses for a short period of time, so long as an adequate degree of liquidity is maintained even at the expense of borrowing, provided there is good prospect of long term revival or resumption of profitable operations ere long.

However, a firm’s cash outflow (i.e., payments to outsiders to meet its obligations) and cash inflow (receipt of money from debtors for sales made to them) go hand in hand and this is a continuous process.

To enable this process to continue smoothly period after period, there is the need to maintain a prudent relationship between current assets and current liabilities. This relationship is called the liquidity ratio or current ratio. It is not necessary for the ratio to be one, i.e., current assets are always equal to current liabilities.

In fact cash payments and cash receipts are always surrounded by a penumbra of doubt. To eliminate business uncertainty, i.e., the possibility of unexpected requirements for cash or unexpected difficulties in obtaining payments due to the company it is important to ensure that current assets exceed current liabilities by an appreciable margin.

There is no rule or formula as to what constitutes a prudent ratio. It varies from business to business and is also affected by a company’s ability to borrow for short periods in times of need by an overdraft facility at its bank.

Since the liquidity ratio establishes relation between current assets, which include stock and work-in-progress, to total current liabilities, it has an inherent defect. There are likely to be marked differences between the degrees of liquidity of the items included although all of them belong to current assets. Such differences may overstate the liquidity of current assets.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For instance, a sudden fall in the demand for a company’s product may raise the stocks of finished goods and thus reduce the liquidity of such stocks. It is more difficult to dispose of work in-progress (or goods-in-process) because of its very nature, at its normal value. Thus, there is need for caution in using the liquidity ratio.

In fact, an improved version of the liquidity ratio is often made use of to measure the performance of a company over time.

The ratio resembles the liquidity ratio very closely, but has the added advantage that it measures those liabilities which have to be met in the near future (again, current liabilities) against only those current assets which have a high degree of liquidity. Obviously these are cash debts and any other highly liquid assets.

The-new ratio — known as the acid test ratio — excludes stocks and work-in-progress from the assets:

It appears to be a more secure way of indicating liquidity than is the liquidity ratio. In most normal circumstances an acid test ratio of 1:1 seems to be desirable. Yet during inflation a firm’s liquidity and working capital may be under severe strain.

ii. Solvency:

A firm is said to be solvent when, irrespective of its liquidity position, its total assets exceed its total liabilities except its share capital (i.e., owner’s capital). A company may be solvent but may face difficulty in meeting its current and short term liabilities due to liquidity crisis.

Solvency is not only a broader term than liquidity, it has longer term implication as well, inasmuch as the ability to repay its long-term liabilities (such as money borrowed by issuing debentures or by mortgaging its office buildings) is brought into consideration, as is the market (saleable) value of its fixed assets, as also its current assets and liabilities.

It may apparently seem that insolvency of a company leads to immediate collapse and cessation of trading. This is an unproved and probably false belief. But insolvency is a more serious problem than liquidity in the sense that the former must lead to difficulty in raising additional finance for remedial measures and for enabling the firm to tide over a temporary or long period of losses.

Under such circumstances a firm has undue dependence on the view taken by its creditors in general and a state of insolvency may therefore persist for a longer or a shorter period. However, insolvency is not totally irremediable.

iii. Gearing:

A company can raise additional funds either by issuing new shares or by borrowing from the public or term lending institutions like IDBI, IFCI, ICICI and so on. Borrowing creates debt problem. The ratio between debt (external capital) and equity capital (owner’s capital) is the gearing (or debt: equity) ratio.

It is expressed thus:

This ratio has an important implication for the company’s capital structure. A highly geared company has a high ratio of debt to equity capital. (We shall speak more about this ratio in the context of ‘Capital Budgeting’). To a shareholder a high gearing ratio offers an opportunity to benefit from the company’s use of the borrowed capital if that use yields profits more than sufficient to pay interest on borrowed capital.

To a banker or a lender a high gearing ratio implies a high degree of risk that a company will not be able to pay its total interest charges out of profits. So a lender is interested in the following ratio which gives a measure of the risk to which a lender is exposed in respect of the interest payments that would be due to him, taking note of the company’s gearing ratio.

The gearing ratio also affected by the rate of price inflation. During the inflation the debtor gains and the creditor loses. Sustained inflation implies that the real burden to a borrower of eventual repayment of principal and interest becomes less than it would otherwise have been. Thus a high gearing ratio is more acceptable during inflation than at other times.

iv. Comments:

In fine we may note that a low profitability ratio may indicate, on the one hand, either poor efficiency, or a period of low demand or the like or, on the other, all the efficiency that competition can enforce. In order to tell which is operating it is necessary to know the structure of the industry.