International trade confers a good deal of benefits on the trading countries. According to the comparative cost theory, if different countries specialise on the basis of comparative costs of commodities, it would enable them to make optimum use of their resources and thereby add to their output, income and welfare of their people.

Gains from trade are broadly divided into two types – Static gains and dynamic gains.

Static gains from trade refer to the increase in production or welfare of the people of the trading countries as a result of the optimum allocation their given factor-endowments, if they specialise on the basis of their comparative costs.

On the other hand, dynamic gains refer to the contributions which foreign trade makes to the overall economic growth of the trading countries.

Static Gains from Trade:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Static gains from trade are measured by the increase in the utility or level of welfare when there is opening of trade between the countries. In modern economics increase in utility or welfare is measured through indifference curves. When as a result of foreign trade, a country moves from a lower indifference curve to a higher one, it implies that the welfare of the people has increased.

To show the static gains from trade, let us take an example –

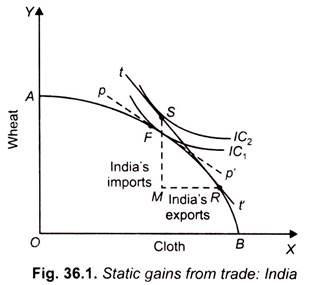

Suppose two commodities, cloth and wheat, are produced in two countries, India and U.S.A., before they enter into trade. Their production possibility and indifference curves for cloth and wheat are shown in Figs. 36.1 and 36.2. It will be seen from Fig. 36.1 that before trade India would be in equilibrium at point F (i. e., producing and consuming at point F) where the price line pp’ is tangent to both production possibility curve AB and indifference curve IC1.The slope of the price line pp’ shows the price ratio (or cost ratio) of the two commodities in India.

India can gain if international price ratio (i.e., terms of trade) is different from the domestic price ratio represented by pp’. Suppose the terms of trade settled are such that we get tt as the terms of trade line showing the price ratio at which goods can be exchanged between India and the U.S.A. Now, with tt’ as the given terms of trade line (i.e., new price ratio line), India would produce at point R at which the terms of trade line tt is tangent to her production possibility curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It will be seen from Fig. 36.1 that at point R, India will produce more of cloth in which it has comparative advantage and less of wheat than at F. Though India will produce at point R on her production possibility curve, where the terms of trade line tt’ is tangent to her production possibility curve AB, it will not consume or use the quantities of wheat and cloth, represented by the point R.

Given the new price ratio represented by the terms of trade line tt’ the consumption of the goods will depend upon the pattern of demand of the country. To incorporate this factor we have drawn social indifference curves IC1, IC2 of the country. These social indifference curves represent the demands for the two goods, or, in other words, the scale of preferences between the two goods of the Indian society.

It will be seen from Fig. 36.1 that the terms of trade line tt’ is tangent to the social indifference curve IC2 of India at point S. Therefore, after trade India will consume the quantities of cloth and wheat as represented by point S.

It is therefore clear that as a result of reallocation of resources and specialising, and producing more of cloth and less of wheat by India and trading with the US she has been able to shift from point F on indifference curve IC1 to the point S on higher indifference curve IC2. This is the gain obtained from specialisation through reallocation of resources and trade and implies that trade enables India to increase her consumption beyond her production possibility curve. (It will be seen that point S lies beyond the production possibility curve AB of India).

It is also worth noting that when specialisation and trade occur, the quantities of the two goods consumed by a country will differ from the quantities of the two goods produced by her without specialisation and reallocation of resources. In Fig. 36.1 whereas India produces the quantities of two goods represented by point R, it will consume the quantities of the two goods represented by the point S. The difference arises due to exports and imports of goods. In Fig. 36.1, while India will export MR quantity of cloth, she will import MS quantity of wheat.

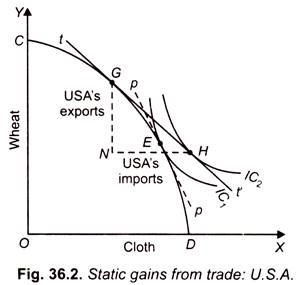

Now consider the position of U.S.A. which is depicted in Fig. 36.2. Given its factor endowments CD is the production possibility curve between wheat and cloth of the U.S.A. It is evident from the production possibility curve CD that the factor endowments of the U.S.A. are more favourable for the production of wheat.

It will also be seen from Fig. 36.2 that before trade the U.S.A. will produce and consume at point E on her production possibility curve CD where the domestic price ratio line and indifference curve IC1 are tangent to it. The USA will gain from trade if it can sell at a different price ratio from pp’. Suppose that the terms of trade line is tt’. With this terms of trade line tt’ the U.S.A. will produce at point G on her production possibility curve CD.

She will now produce more of wheat in which she has comparative advantage and less of cloth than before. On the other hand, given the price ratio as represented by the terms of trade line tt’ the U.S.A. will consume the quantities of the two goods given by the point H where the terms of trade line is tangent to her indifference curve IC2. Welfare of its people has increased. It is therefore clear that through reallocation of resources between the two goods and specialisation in the production of wheat and consequently trade with India has enabled the U.S.A. to shift from her lower indifference curve IC1 to her higher indifference curve IC2. This is the gain which she obtains from trade.

By comparing the production and consumption points of the U.S.A. it will be observed that the U.S.A. will export NG amount of wheat and import NH amount of cloth.

It is worth remembering that while in case of constant opportunity cost each country attains complete specialisation, that is, it produces one of the two goods after trade, in case of present increasing opportunity cost specialisation is not complete. In case of increasing opportunity cost as shown in Fig. 36.1 and Fig. 36.2 a country produces only a relatively large amount of the good in which it has comparative advantage.

Dynamic Gains from Trade- International Trade and Economic Growth:

We have seen above that the comparative cost theory that specialisation followed by international trade makes it possible for the countries to have more of both commodities than before. This additional production of commodities is the gain which flows from specialisation to different countries in the production of different goods and then trading with each other. Specialisation by different countries in the production of different goods according to their comparative efficiency and resource endowments brings about an increase in the total world production by increasing the level of their productivity.

However, these gains from specialisation and trade made possible by reallocation of the given resources along a given production possibility curve are one-time event and are therefore called static gains from trade. Empirical evidence shows that such gains are quite small, less than one per cent of GDP of the trading countries. However, in addition to static gains there are dynamic gains from trade.

These dynamic gains from trade refer to the gains from trade that accrue to the countries over time because trade induces economic growth of a country and brings increase in efficiency in the use of resources by a country. It is this trade that makes possible the division and specialisation of labour on which higher productivity of different countries is so largely based.

If the various countries could not exchange the products of their specialised labour, each of them would have to be self-sufficient (i.e., each of them would have to produce all goods it requires, even those which it could not produce efficiently) with the result that their productivity and standard of living will go down. Thus according to Professor Haberler, “International division of labour and international trade, which enable every country to specialise and to export those things which it can produce cheaper in exchange for what others can provide at a lower cost, have been and still are one of the basic factors promoting economic well-being and increasing national income of every participating country.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We thus see that the main gain from specialisation and trade is the increase in national production, income and consumption of the participating countries. But the above explanation of gains from trade in terms of comparative cost theory deals only with static gains from trade, that is, the gains which accrue to a country from specialisation brought about by reallocation of a given amount of resources.

As pointed out above, the importance of and gain from international trade follows from the theory of comparative cost. Specialisation by different countries according to their production efficiency and factor endowments ensures optimum use and allocation of resources of the countries. Differences in production possibilities and costs of production of various products between different countries of the world are so great that tremendous gain in terms of additional output and income accrues to the world community from international specialisation and trade. For instance, the relative differences in cost of production of industrial products and food and raw materials between developed and developing countries are almost infinite in the sense that either type of these countries cannot produce what they buy from the other.

But the theory of comparative cost is static. It indicates only those gains which accrue to the trading countries as a result of the differences in given costs of production and given production possibilities of various products at a given point of time. As pointed out above, besides the static gains indicated by comparative cost theory, international trade bestows very important indirect gains and benefits, which are generally described as dynamic gains, upon the participating countries.

These dynamic gains also promote economic growth in the participating countries. It is worth noting that both developed and developing countries have obtained benefits from trade. The international trade has contributed a good deal to the economic development of underdeveloped countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To quote Professor Haberler again, “If we were to estimate the contribution of international trade to economic development especially of the underdeveloped countries solely by the static gains from trade in any given year on the usual assumption of given production capabilities, we would indeed grossly underrate the importance of trade. For over and above the direct static gains dwelt upon by the traditional theory of comparative cost, trade bestows very important indirect benefits upon the participating countries”.

Dennis Robertson described foreign trade as “an engine of growth.” With greater income and production made possible by specialisation and trade, greater savings and investment become possible and as a result higher rate of economic growth can be achieved. Through promotion of exports, a developing country can earn valuable foreign exchange which it can use for the imports of capital equipment and raw materials which are so essential for economic development.

Therefore, Professor Haberler argues that since international trade raises the level of income, it also promotes economic development. He thus remarks – “What is good for the national income and the standard of living is, at least potentially, also good for economic development; for the greater the volume of output the greater can be the rate of growth—provided the people individually or collectively have the urge to save and to invest and economically to develop. The higher the level of output, the easier it is to escape the ‘vicious circle of poverty’ and to ‘take off into self-sustained growth’ to use the jargon of modern development theory. Hence, if trade raises the level of income, it also promotes economic development.”

Explaining the dynamic or growth benefits, Sawyer and Sprinkle write, “A country engaging in international trade uses its resources more efficiently. Businesses in search of profits will naturally move resources such as labour and capital into industries with a comparative advantage. The resources employed in the industry with a comparative advantage can produce more output which leads to a higher real GDP. A higher real GDP tends to lead to more saving and therefore more investment. The additional investment in plant and equipment usually leads to a higher rate of economic growth. In a roundabout way gains from international trade grow larger over time. What is happening is that economies that are more open grow faster than the closed economies, everything else equal.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another trade benefit which accrues to the countries (even small countries) is the economies of scale which occur in some industries which lower unit cost of production when these industries expand. Economies of scale or what are called increasing returns to scale imply that as an industry expands, its unit cost of production falls. Highlighting the significance of increasing returns to scale of trade, Sawyer and Sprinkle write, “There may be even greater benefits from trade for small countries. For industries subject to increasing returns to scale, free trade may allow an industry in a small country an opportunity to expand its production and lower its unit cost. This reduction in cost makes the industry more efficient and allows it to compete in the world markets. Imagine the loss of opportunities for producers in small countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark if they did not have free access to the European countries.”

Similarly, the Canadian economy benefited a lot from its trade with large US economy. The free access to Canadian firms in the US and Mexican markets under the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) permitted Canadian firms to expand and lower unit costs making their industries more efficient leading to the increase in their output.

Another important gain from trade is the effect on competitive forces and prices of developing countries when they open up to the world economy. The opening up of the developing countries such as India is to enhance competition in the domestic market which ensures lower prices in the domestic market. For example, in India under economic reforms initiated since 1991, the Indian economy was opened up and in view of competition from imports to survive and expand the big Indian firms was forced to reduce their prices as their monopoly power ended by the entry of foreign products at cheap rates.

Even Maruti Company which enjoyed a high degree of monopoly power in the Indian car industry had to improve its quality and fix prices of its models at reasonable levels. Thus opening up of the Indian economy led to the increase in quality of goods as well as lower prices. This caused increase in production of goods not only for the domestic economy but also for exporting them to other countries.

Further, through foreign trade, developing countries get material means of production such as capital equipment, machinery and raw materials which are so essential for economic growth of these countries. There has been rapid technological progress in the developed countries. This advanced and superior technology is incorporated or embodied in various types of capital goods.

It is thus clear that developing countries derive tremendous gains from technological progress in the developed countries through the imports of capital goods such as machinery, transport equipment, vehicles, power generation equipment, road building machinery, medicines, and chemicals. It is worth mentioning here that the pattern of import trade of the developing countries has changed in the last several years and now consists of greater quantity of various forms of capital goods and less of textiles.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Furthermore, even more important than the importation of capital goods is the transmission of technical know-how, skills, managerial talents, entrepreneurship through foreign trade. When the developing countries come to have trade relationship with the developed countries, they also often import technical know-how, with all their skills, managers, etc., from them. With this they are also able to develop their own technical know-how, managerial and entrepreneurial ability. The growth of technical know-how, skill and managerial ability is an important requisite for economic development of developing countries.

Professor Haberler rightly says – “The late-comers and successors in the process of development and industrialization have always had the great advantage that they could learn from the experiences, from the successes as well as from the failures and mistakes of the pioneers and forerunners. Today the developing countries have a tremendous, constantly growing store of technical know-how to draw from. True, simple adoption of methods, developed for the conditions of the developed countries, is often not possible. The adaptation is surely much easier than the first creation. Trade is the most important vehicle for the transmission of technological know-how. Today there is a dozen industrial centres in Europe, the U.S., Canada, Japan and Russia which are ready to sell machinery as well as engineering advice and know-how.”