In this article we will discuss how trade can contribute to economic growth of a country.

Although the rate of economic growth and the space and pattern of economic development depends primarily on internal conditions in developing countries, international trade can make significant contribution to economic development. The traditional theories of trade examine how growth in production capabilities can affect international trade.

Clearly, growth can have a major impact on international trade. There is also likely to be an impact in the other direction—from trade to growth. Exposure to international trade can have an impact on how fast a country’s economy can grow and how fast its production facilities are growing over time.

The classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo first found interest in the role of trade in economic development. They have sang the praise of free trade based on comparative advantage. The principle of comparative advantage holds that each country will benefit if it specialises in the production and export of those goods that it can produce at relatively low cost. Conversely, each country will benefit if it imports those goods which it produces at relatively high cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The classicists advocated the doctrine of laissez-faire (non-interference by the government) even in international trade (and not just in domestic matters). Such adherence to completely free trade, they thought, would promote the maximisation of welfare for the world and the member countries in the world trading system.

Notwithstanding its limitations, the theory of comparative advantage is one of the deepest in all types of economies. Those countries which disregard comparative advantage ultimately have to pay a heavy price in terms of their living standards and economic growth.

As P. A. Samuelson and W. D. Nordhaus convincingly argue:

“Free trade promotes a mutually beneficial division of labour among nations; free and open trade allows each nation to expand its production and consumption possibilities, raising the world’s living standard. Protectionism prevents the forces of comparative advantage from to maximum advantage.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, there is dissatisfaction among LDCs as to the virtue of completely free trade and most such countries feel that it is not the ideal policy for them. They feel that they are partners in global trade since the gains from trade are not equally shared by developed and developing countries.

This very feeling gets reflected in the North-South conflict which has created the demand for a new international economic order. Given their level of poverty and some special problems which they have been facing over the years, developing countries often treat the laissez-faire prescription as inappropriate.

So, any discussion of the role of international trade in promoting economic development must take into account the special problems faced by the developing countries in international trade and the policy constraints they face in tackling them.

Trade, undoubtedly, has several benefits. It promotes growth and enhances economic welfare by stimulating more efficient utilisation of factor endowments of different regions and by enabling people to obtain goods from efficient sources of supply. Trade also makes available to people goods which cannot be produced in their country due to various reasons.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The role of trade in enhancing consumer’s choice (even delight) is tremendous. The foreign trade multiplier, shows how an injection of income arising out of trade can lead to economic expansion.

According to A.C. Cairn cross:

“As often as not, it is trade that gives birth to the urge to develop, the knowledge and experience that make development possible, and the means to accomplish it.”

An Overview of the Developing Countries:

It may be noted at the outset that LDCs are not a homogeneous group. There are many differences in levels of income, types of industrial structure, degree of participation in international trade (or the degree of economic openness) and types of problems faced in the world economy.

In spite of the diversity among LDCs, a list of Characterizations of these countries is useful for emphasizing that they are very different from the industrialised countries. In general, the LDCs are characterised as having low per capita incomes and a relatively low per cent of their population in urban areas.

In addition, population growth rate, the share of agriculture in GDP, and infant mortality rates are higher and life expectancy is shorter than those in high- income countries. Finally, the share of manufactured exports in total exports tends to be lower in developing countries than in high-income countries.

E. Haberler lists the following benefits of trade to stress the importance of trade to development of the less developed countries:

1. Trade provides material means (capital goods, machinery, and raw and semi-finished material) indispensable for economic development.

2. Trade is the means and vehicle for the dissemination of technological knowledge, the transmission of ideas, for the importation of know-how, skills, managerial talents and entrepreneurship.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Trade is also the vehicle for the international movement of capital, especially from the developed to the underdeveloped countries.

4. Free international trade is the best anti-monopoly policy and the best guarantee for the maintenance of a healthy-degree of free competition.

The Role of Trade in Economic Development:

In discussing the role of trade in fostering economic development, we have to examine various different issues, viz, the static effects of trade, the dynamic effects of trade and export pessimism or secular deterioration of the terms of trade of LDCs. In this context, we have access to discuss trade policies of the developing countries.

1. The Static Effect of Trade on Economic Development:

International trade enables an LDC to get beyond its PPC and improve its welfare. It can consume more than what it is capable of producing through specialisation and exchange. An LDC can improve its well-being by specialising in and exporting the relatively less expensive domestic goods and importing goods which are relatively more expensive. Even if a country’s production does not change at all, there are still gains from exchange if there is a difference between internal relative prices in autarky and those which can be obtained internationally.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In addition, the characteristics of the imported goods either in terms of quantity for customers or productivity in the case of capital and intermediate imports, may improve the economy ‘s ability to meet consumer desires for better quality goods or larger volume of goods made available by improved technology. Imports may also help remove bottlenecks and enable the economy to operate closer to its PPC—that is to say, more efficiency on a consistent basis.

i. Employment Generation:

Due to specialisation there is a relative expansion of the sectors using relatively more intensively an LDCs abundant factor—which is labour. For most LDCs, specialisation according to comparative advantage helps to expand labour-intensive production instead of more modern, capital-intensive production.

This means expanding traditional agriculture, primary products, and labour-intensive light manufactures. International trade thus stimulates employment and puts upward pressure on wages as has been suggested by the Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) theorem. However, most LDCs are labour-surplus countries. So, an increased demand for labour is unlikely to raise the wage rate much.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Export Instability:

Moreover, the relative growth in the production of traditional goods may not be desirable if such growth is at the expense of modern manufacturing. Due to low income and price elasticities of demand for such goods and the instability of supply of agricultural and primary products due to natural (weather) conditions, greater specialisation in these goods can result in a greater instability of income even in the short run.

iii. Adverse Terms of Trade:

In addition, since an LDC is a small country (in the sense that it cannot exert any influence on the prices of its exports and imports), expansion of export supply may lead to undesired terms of trade movements that will-reduce the static gains from trade. This may lead to a distribution of gains from trade in favour of the industrially developed countries.

iv. Greater Dependency:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, expanding production of basic labour-intensive goods and relying on the industrialised countries for technology and skill-intensive manufactures and capital goods often leads to excessive economic dependency. It also links the economic health of the developing country to that of the industrialised country.

v. Vent for Surplus:

Both the classical (Ricardian) and the modern (H-O) theories of international trade are based on the assumption that production in each trading country takes place under conditions of full employment. But full employment does not prevail in LDCs. So, trade theories cannot be applied in such countries to predict the impact of trade on production, consumption, distribution and social welfare.

Yet, there is another potential gain from trade, as has been pointed out by Hla Myint (1958). According to Myint, due to unemployment on LDCs, actual output is less than its potential output. By utilising its manpower fully an LDC can produce more products and its supply may exceed domestic demand.

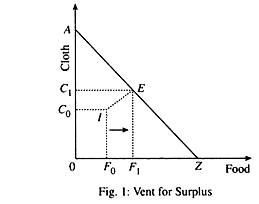

This excess supply can be disposed of in the form of export. In this sense a ‘vent for surplus’, i.e., a larger market that will permit a labour surplus country to increase its employment and output, as is shown by a movement from a point such as I (inefficient point), inside the PPC to a point E (efficient point) on the PPC in Fig. 1.

Myint suggests that vent for surplus convincingly explains why countries start to trade, while the theory of comparative cost helps to understand the types of commodities countries ultimately export and import. No doubt the gains in income, employment and needed imports can render considerable help to the whole process of development.

In short, the static gains from trade for an LDC originates from the traditional gains from exchange and specialisation as will follow from a vent for surplus. However, due to the lack of sufficient flexibility in traditional (largely subsistence) economies and the nature of the traditional labour-intensive exports, the relative gains from trade may be less than those from more flexible and progressive industrial economies and may be further reduced by the undesirable effects of increased economic instability and secular deterioration of the terms of trade. No doubt in the process of economic development we find changes in the economic structure and sectoral distribution of income.

This occurs in response to changes in relative prices brought about by international trade. However, the economic systems of the LDCs tend to be somewhat unresponsive to changing price incentives, at least in the short run.

So, factors of production may not move easily to the expanding low-cost sectors from the contracting higher-cost sectors. In such a situation the process of adjustment assumes the characteristics of the specific-factors model. Consequently, the gains from specialisation are reduced correspondingly.

2. The Dynamic Effects of Trade on Economic Development:

Perhaps the maximum potential impact of trade on development lies in its dynamic effects. As D. Salvatore has put’ it- “While the need for a truly dynamic theory cannot be denied, comparative statics can carry us a long way forward incorporating dynamic changes in the economy into traditional trade theory. As a result, traditional trade theory, with certain qualifications, is of relevance even for developing nations and the development process.”

On the positive side, the expansion of output made possible by access to the wider international markets enables the LDC to exploit economies of scale that would not be possible with a narrow domestic market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This means that industries which are not internationally competitive in an isolated market may achieve competitiveness by way of international trade if there are potential economies of scale. If LDCs can take advantage of economies of scale, they can reduce costs of production and sell their products at low prices in international market.

Promotion of Infant Industries:

Moreover, comparative advantage is a dynamic concept. In the real world, we find changing pattern of comparative advantage over time. As a developing nation accumulates capital and improves its technology, its comparative advantage shifts away from primary products to simple manufactured goods first and then to more sophisticated ones.

Thus, with economic development, international trade can foster the development of infant industries and make them internationally competitive by providing the market size and exposure to products and processes that is unlikely to happen in closed (isolated) economy. This is why the most important argument for protection in LDCs is the infant industry argument. It is essentially an argument in favour of protection to gain comparative advantage.

This is why for protecting infant industries trade policy restraints in most LDCs are used, at least in the early stages to restrict imports or promote exports. To some extent, this has already happened in Brazil, Korea, Taiwan, Mexico and some other developing countries. However, there are various problems with using the policy in practice. Infants never grow adult in some high protected environments and there is need for continuation of protection for ever.

Other Dynamic Influences:

Perhaps the maximum possible impact of trade on development depends on its dynamic effects. Prima facie, the expansion of output brought along by access to the larger international markets permits the LDC to take advantage of economies of scale that do not arise in the limited domestic market.

Thus, industries which are not internationally competitive in a narrow and isolated domestic market may well gain competitiveness as a wider market created by international trade. Trade creates an opportunity to exploit potential economies of scale. Furthermore, comparative advantage keeps on changing over time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, as economic development takes place, international trade promotes the growth and ensures the maturity of infant industries which become internationally competitive by being able to exploit the wider market created by trade.

A wider market also exposes an LDCs products and processes in international market and creates pressure on the industries of LDCs to improve product quality and reduce product price so that these are accepted in the rest of the world. In short, international trade makes protected domestic industries internationally competitive.

Other dynamic influences of trade on economic development arise from the positive competitive effects of trade, increased investment resulting from changes in the economic environment; the increased dissemination of technology into the LDC (as has been suggested by the product life cycle model), exposure to new and improved products and changes in institutions accompany the increased exposure to different countries, cultures and products. Trade fosters domestic competition and acts as an instrument of controlling monopoly.

Openness to trade can affect the technology that a-country can use. We may now discuss the mechanism in detail. Trade policies give of country access to new and improved products. No doubt capital goods are an important type of input into production that is largely imported by LDCs at lower stages of development. Trade allows a country to import new and improved capital goods, which “embody” better technology that can be used in production to raise total factor productivity.

The foreign exporters can also enhance the process, for instance, by advising the importing firms on the best ways to use the new capital goods. Some empirical studies show that the gains from being able to import unique foreign imports that embody new technology can be larger than the traditional gains from trade, highlighted by the classical theory.

According to T. A. Pugel, in a more general way, openness to international activities leads the firms and people of the country to have more contact with technology developed in other countries. This greater awareness makes it possible for an LDC to gain the use of new technology—through purchase of capital goods or through licensing or initiation of the technology.

Great economic openness is likely to have a favourable effect on the incentive to innovate. Trade is likely to put additional competitive pressure on the country’s firms. The pressure drives the firms to seek better technology to raise their productivity in order to achieve greater international competitiveness.

Trade also provides a larger market in which to earn returns to innovation. Its sale into foreign markets provides additional returns, then the incentive to innovate increases, and firms devote more resources to R & D activities.

Openness thus can enhance the technology that a country can use—both by facilitating the diffusion of imported technology into the country and by accelerating the indigenous development of technology. Furthermore, these increases in current technology base can be used to develop additional innovations in the future.

The current technology base becomes a potent source of increasing returns over time to ongoing innovation activities. The growth rate for the country’s economy (and for the world as a whole) increases in the long run.

In short, economic openness can accelerate long-run economic growth. This indicates an additional source of gains from international trade (or from openness to international activities more generally). Empirical studies show that there is a strong positive correlation between the growth rate of a country and its international openness. This is not a proof of causation, ‘but it is consistent with the theoretical analysis that suggests why openness can raise growth.

Trade as a Hindrance to Growth:

Critics, however, have pointed out that conditions in developing countries are not very different from those of industrial countries. So that the application of the static principle of comparative advantage may not be helpful in providing appropriate guidelines for trade and specialisation in a dynamic LDC environment. While trade can be beneficial to nations and the world as a whole, it can also have harmful effects on some countries and as also on the world entire.

The international trading system is biased against the developing countries, particularly the poor among them, because of factors like their weak bargaining power vis-a-vis the advanced countries, the participation gap, dependence on the developed countries for various needs, etc.:

The important harmful effects of trade are the following:

1. Trade may lead to indiscriminate exploitation of natural resource, particularly of developing nations. Trade has been resulting in the drain of resources from the developing to developed countries.

2. Trade also causes environmental problems because of the indiscriminate exploitation of resources and location/relocation of polluting and hazardous industries in the developing world for the benefit of the developed world.

3. The deterioration of the terms of trade of the developing countries causes large income transfers from the developing to the developed countries.

International trade may also give rise to demonstration effect in the developing countries. Demonstration effect, a term associated with Nurkse, refers to the tendency of poor people to imitate the life styles of the rich.

In international economics, it refers to the tendency of the people of developing countries to follow the consumption habits of the people of the advanced countries by importing luxury goods. This could have harmful social and economic effects. It could also have some favourable effect if it can encourage the development of the domestic industries of the developing countries.

Another important harmful effect of trade is what is described as the backwash effect. Some of the domestic industries of the developing countries, particularly small scale, which are unable to compete with the well-developed industries of the advanced countries, could be destroyed or damaged by unregulated imports.

India has had a paradoxical policy of reserving many items for the small scale sector but allowing the import of these items. The recent trade liberalisation is adversely affecting the agricultural, often subsistence, sector of many developing countries even as the agricultural sector is heavily protected in the developed world.

Globalisation and free trade are now adversely affecting the developed countries, too because of the edge the developing countries have over the developed ones in the production of many products. Trade also results in the introduction of pep and cola cultures to the developing countries which have important social implications.

Two main reasons for not so remarkable improvement in growth due to trade in LDCs are:

(i) Absence of perfect competition (and the consequent distortion of commodity and factor prices) and

(ii) The absence of full employment (due to existence of not only surplus labour but also surplus productive capacity).

For these reasons, if we are to get a balanced view of the effects of international trade on development we have to refer to some important disadvantages of free trade for an LDC, more so in view of the fact that these problems can have important implications for trade policy.

1. Externalities:

The static theory of comparative advantage ignores the very important fact that most markets in LDCs are imperfect. This implies departure from the Pareto optimality conditions. Market imperfections create an undesirable consequence. Private costs and benefits differ from social costs and benefits mainly due to the existence of economic externalities.

Any reliance on market prices in such an environment can lead to the emergence of a pattern of trade which, is largely inconsistent with both relative social costs-and long-term development goals of the country, e.g., if the growth of an industry does considerable damage to the physical environment.

2. Differential Impact of Trade:

In a more general way, the overall effect of growth in exports on the growth and development of the entire economy is likely to vary from commodity to commodity. The reason is easy to find out. In a broader dynamic context, the economy- wide production linkages vary among different commodities or sectors.

Industries producing certain strategic inputs like steel, coal and power or oil may act as leading sectors or ‘growth poles’ for the entire economy, while others—such as primary products—will act as the lagging sectors having little or no linkage effect outside their own sectors.

3. Variation in Returns to Scale:

Returns to scale may also vary among commodities. This means that an LDC is unlikely to have a relative cost advantage in a particular product since the domestic market is too narrow to permit cost-efficient production.

However, there might exist a comparative advantage in the same product at a higher level of output. In a like manner, a product may have a relative cost advantage at present but its production is characterised by decreasing returns to scale. So it may have very limited export potential.

4. Market Imperfections and Government Policy:

The domestic supply and demand conditions that underlie both current and future comparative advantage is likely to be influenced both by market imperfections and by restrictive, and at times unrealistic, domestic economic policies.

5. Unequal Distribution of Gains from Trade:

Finally, the operation of markets and characteristics of traded goods differ between the developing countries and the industrialised countries. Such differences result in a disproportionate share of the benefits of trade being captured by the industrialised countries.

What is worse is that such differences often lead to greater dependence of LDCs on DCs. This is a major source of potential development problems for countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh which have a colonial heritage and an enclave economic structure.

As D. Salvatore comments- “With developing nations specialising in primary commodities and developed nations specialising in manufactured products, all or most of the dynamic benefits of industry and trade accrue to developed nations, leaving developing nations poor, undeveloped and dependent.” Two issues related to these differences are export instability and secular (long-run) deterioration of the terms of trade. In this sense, trade acts as hindrance to growth.

It is to this issue that we turn now:

Export Instability:

Exports of LDCs tend to fluctuate more sharply from year to year than are found in industrialised countries. Due to the relatively high degree of openness of many LDCs (i.e., a high ratio of foreign trade to GDP), variability in the export sector leads to fluctuations in GDP and the domestic price level. Thus, business cycles get transmitted from developed to developing countries through international trade.

This causes considerable uncertainty to producers and consumers. In addition, export instability makes it more difficult to carry out planning for development. When export earnings are high in ‘good’ years, new projects are started by importing necessary equipment.

But when export earnings subsequently decline, the planning process receives a severe jolt. The reason is that foreign exchange is not available to complete and to operate the projects. The end result is huge resource waste and, a serious distortion to the planning process.

Causes:

There are three main causes of export instability. There is a common link among the causes since all originate from the fact that many LDCs are relatively more engaged in the export of primary products than of manufactured goods. While the first two reasons pertain to price fluctuations, the third one focuses on variations in total export earnings.

Immeserising Growth:

J. N. Bhagwati has even pointed out that a large country actually could be made worse-off by an improvement in its ability to produce the products it exports. This is known as immeserising growth. By expanding its ability to produce food as its export good the large country increases its supply of exports (expands its willingness to trade). This reduces the relative price of food in world markets. At the same time this causes an increase of the relative price that it must pay for its imports of car.

The decline in the country’s terms of trade is so bad that it outweighs the benefits of the greater ability to produce exportable goods. In short, growth that expands the country’s Willingness to trade can result in such a large decline in the country’s terms of trade that the country is worse off.

No doubt most of the gains from trade in the past have accrued to DCs. But this does not mean that trade is actually harmful. There are cases where a balanced trade may actually have hampered economic development. However, in most cases, it can be expected to provide invaluable assistance to the development process.

Dutch Disease:

Booming primary exports may fail to stimulate development due to deterioration of the terms of trade for a special reason, known as the Dutch Disease. This problem was first detected in Netherlands in the 1960s when major reserves of natural gas were discovered.

The ensuing export boom and the balance of payments surplus pressurized new prosperity. Instead, however, during the 1970s, the Dutch economy suffered from rising inflation, declining export of manufactures, lower rates of income growth, and rising unemployment.

Max Corden and Peter Nearly first described the strange phenomenon of the Dutch Disease, in which a country that receives higher export prices or a larger inflow of foreign capital may be worse-off than without the windfall.

Trade Policy and the LDCs:

We may now briefly discuss how trade policy can be used to promote growth and developments, in countries like India. The focus is on three areas: export instability, terms of trade deterioration and inward-versus outward-looking development strategies.

1. Stabilisation of Export Prices and Earnings:

Three main types of policies can stabilise prices of export earnings in LDCs.

These are:

(a) International Buffer Stock Agreement:

This is essentially a means of generating larger benefits for LDCs in the world economy. Under such an agreement, producing nations (often joined by consuming nations) set up an international agency endowed with funds and a stock of the commodity. If the world price of the good falls below the flour the agency will buy it to bring the price up to the flour. On the other hand, if the world price rises above the ceiling, the agency will sell the good to bring the price down to the ceiling. If the agency achieves success, then both producing and consuming nations will gain.

(b) International Export Quota Agreement:

Under an export quota agreement, producing countries choose a target price for the good and make a forecast of world demand for the coming year. They then determine the quantity to be offered for sale which will, in conjunction with estimated world demand, yield the target price. If the forecast of demand is correct and supplying countries adhere to their quotas, then the next year’s price will reach its target level.

The export quota agreement contains a mechanism for keeping prices stable. If the world price falls due to a fall in demand, the export quotas of the supplying countries will be tightened and the price will rise to the target level. Likewise, if the world price rises, the quotas will be relaxed and the price will fall to the target level. Thus, this policy provides some degree of stability to export prices.

(c) Compensatory Financing:

Under this scheme, an international agency is provided with necessary funds. It forecasts the growth trend of the export earnings of each participating LDC. The IMF has such a facility since 1963. Where export earnings of an LDC falls, the agency ensures that there is a steady flow of foreign exchange to the LDC for the purchase of development imports. This method is superior to international consumption agreements (ICAs) since compensatory financing does not interfere with the allocative function of prices.

2. Combatting a Secular Deterioration of the Terms of Trade:

Four broad measures can be adopted for preventing a long-term deterioration of the terms of trade:

(a) Export Diversification:

One strategy adopted to prevent the terms of trade of LDCs from deteriorating is increased diversification into manufactured goods by the LDCs. For making this measure effective, greater education of the labour force is essential. This will enable LDCs to learn to produce manufactured goods by adopting modern technology developed in advanced countries so that the LDCs do not fall behind in the technology growth race.

Moreover, the elasticities of demand for manufactured goods are also much higher than those of primary products. So there is hardly any chance of price fall due to overproduction of manufactured goods. The manufactured goods can be labour-intensive goods in accordance with the factor endowments of LDCs.

(b) Export Cartels:

By forming cartels like the OPEC, LDCs, in general, can organise to obtain a larger share of the gains from trade in the world economy. A cartel will be successful in case of products for which world demand is inelastic—both in the short run and in the long run, as is the case with oil.

There are three other conditions of cartel success:

(i) All exporting countries have to be part of the process,

(ii) Substitutes for the product under consideration should not be readily available at competitive prices,

(iii) Members of the agreement must not cheat on the agreement.

(c) Import and Export Restrictions:

A third policy is the use of restrictions to improve the terms of trade. A country with the ability to influence world prices can improve its welfare level by imposing import tariff (in the absence of retaliation from other countries).

However, to influence the terms of trade, a country has to be large in the economic sense, in one or more of its export commodities. But this is not the case with most LDCs. Furthermore, any reduction in the volume of trade by the use of restrictive policies will not be effective for LDCs.

It is because by imposing such restrictions LDCs will be depriving themselves of necessary developmental imports (e.g., machines, transport equipment, components, etc.) from the industrial countries and will create price distortions into their economies. This will do considerable damage to development.

(d) Economic Integration:

Finally, developing countries can help themselves through economic integration by forming free trade areas or common markets. By this the LDCs can avoid the deterioration in their TOT with industrialised countries by having greater participation in regional trade (i.e., trade among themselves having similar factor endowments). Through economic integration LDCs can have more negotiating and bargaining power in world markets because they will be able to act as a united front.

In addition, the wider market within the region may stimulate investment. The emergence of a strong base for trading manufactured goods and the export diversification is needed to avoid export instability and deterioration of the terms of trade.

Such integration is likely to facilitate the flow of new technology and promote development in LDCs without locking them into specialising in the production of primary goods. Instead, LDCs can be enabled to take best advantage of their underlying comparative advantage. However, such a scheme will not be very effective unless its benefits are evenly distributed among the member countries.

3. Trade Strategies for LDCs:

Our study of the relation between international trade and economic development will not be complete unless we are able to identify the appropriate among two competing strategies regarding the trade sector. An inward-looking strategy seeks to withdraw, at least in the short run, from full participation in the world economy.

This strategy emphasises import substitution, i.e., the domestic production of goods at home that would otherwise be imported. This will initially lead to considerable foreign exchange saving and, ultimately, generate new manufactured exports without the difficulties associated with the exports of primary products provided two conditions are satisfied. First, if economies of scale are important, second, the infant industry argument applies.

This strategy uses tariffs, import quotas, subsidies to import-substitute industries, and similar measures. In contrast, an outward- looking strategy emphasises participation in international trade by encouraging efficient allocation of resources without causing price distortions. It does not use policy measures to shift production in an ad hoc (arbitrary) basis serving the domestic market and foreign markets.

It is essentially an application of the principle of comparative advantage in the area of production so as to ‘get prices right’. The focus is primarily on export promotion, whereby policy steps such as export subsidies, encouragement of skill formation in the work force, and the use of more advantageous technology and tax concessions are used to generate more exports, particularly labour-intensive manufactured goods in accordance with the H-0 theorem.

Even the World Back has recommended that LDCs adopt more outward-oriented policies. The reason is that sooner or later import substitution policy comes to a halt due to the narrow size of the domestic market for industrial goods. But when a country produces for the export market there is scope for endless expansion as there is no limit for the much wider and ever expanding global market.

Difficulties:

However, the practical application of the outward looking strategy is beset with a number of difficulties:

(i) Protectionist Barriers:

The expansion of manufactured exports, from successful countries such as Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore (the so-called four Asian Tigers) can run into protectionist barriers in the industrialised countries.

Since, the export of labour- intensive manufactured goods from such countries threaten long-term existing industries in industrialised countries (e.g., shoes and textiles), restrictions such as Multifiber Arrangement in Textiles and apparel may obstruct this development strategy sooner or later.

(ii) Skill Constraint:

Much like the import substitution strategy, the export promotion strategy also runs into another difficulty—shortage of skilled labour. The export promotion strategy may require skills in the labour force that are not yet fully developed and will require a huge commitment of resources at the initial stage of development. Most LDCs do not have sufficient resources to follow this path.

(iii) Fallacy of Composition:

There is a fallacy of composition in the outward-looking strategy in the sense that what is good for one country is not beneficial for its trading partners. The reason is that while any one country may be favoured by high price elasticity of demand for its exports of manufactured goods, the demand facing all developing countries is less elastic than that faced by a single country. Substantial price-reductions are likely to occur if all developing countries follow the same escape route from export stagnation.

(iv) Lack of Association between Exports and Industrialisation:

Some empirical studies find lack of any positive correlation between export growth and pace of industrialisation. Some studies even suggest that such positive link, if any, occurs only above some threshold income level.

An over-riding issue in the relation between trade and development is whether there is conflict between the gains from the international trade and development of economy. The entire question of the link between ‘trade and growth’ has traditionally been a subject of interest among economists worldwide. Contributing to the understanding of the complex mechanics of growth and trade, interest expanded and theories proliferated.

When economists discuss the role of international trade in the process of economic development, they tend to adopt one of four general views. First view is one what Diaz Alejandro describes the ultra-pro trade biased obiter-dicta of the professional mainstream. The second view is still very much a part of the orthodoxy of trade theory.

Models embodying both traditional free trade assumptions and some market distortions can generate results in which free trade is neither the best policy available nor welfare improving for all the trading countries.

Thirdly, conservative orthodoxy seeks to describe ways in which differences in economic structure b/w countries bias the gains from trade in favour of the developed industrialised economies and against the under-developed, non-industrialised economies. The view is structuralist. Final view is based on a radical perspective which asserts that trade and economic specialisation cause a sharp polarisation of the world into a developed core and an underdeveloped periphery.

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century gave birth to a new mode of production called ‘capitalism’. Commodification of social relation is a basic principle of capitalism. The development of capitalism comes to depend on the accumulation of capital through the progressive transformation of a part of surplus value into productive capital.

Capitalism as a historical reality has the economic necessity to engulf the hither to untouched backward economies to make itself a global phenomenon. The fallout of capitalism is therefore internationalization of capital and unification of world economy i.e., involvement of different countries in the network of world market.

Let us make a brief review of the stylized facts of international trade, theoretical developments occasioned by the empirical regularities. The 19th century pattern of trade was one in which Britain, followed by other Western countries, exported, manufactures to the rest of the world, the colonies and the ‘regions of recent settlement’ exported raw materials and food with capital exports from Europe financing the creation of the necessary physical infrastructure in the primary exporting regions.

In the 50s Nurkse, Prebisch, Lewis were all pessimistic or at least sceptical about the power of trade to continue to serve as an ‘engine of growth’ in LDCs as it had done up to 1914—when the First World War begun (1914-1918). The 60s and early 70s however saw tremendous expansion of world trade driven by historically unprecedented growth rates in Japan, West Europe and USA.

Can foreign trade have a propulsive role in the development of a country? The issue dates back to the period of economic development when Adam Smith makes an enquiry into the nature and causes of Wealth of Nations (1776). His view is that international trade expands market and facilitates division of labour. Division of labour is the key to industrial development and thus trade has a beneficial role to economic development.

If country A has more efficiency in the production of y, it will be mutually advantageous of both the countries to involve in international trade. Country A should specialise in the production of X, while country B should specialise in the production of Y.

The subsequent classical economists considered comparative advantage as determining the pattern of trade. Every trading country is able to enjoy higher real income by specialising in production according to its comparative advantage.

The gains from trade arising from comparative advantage may be called static gains from trade. The static gains facilitate the growth to the extent that by efficient reallocation, the NY of the country can group. Classical economists focused attention on the indirect dynamic benefit.

Every extension of the market generates forces which work to improve the processes of production. Mill clearly observes the scope of increasing productivity of an LDC by means of foreign loan finance and capital. Hicks argues that if production is subjected to increasing returns, the total gains from trade will exceed the static gains from a more efficient allocation of resources.

For a small country with no trade there is very limited scope for large scale investment in advanced capital equipment. Specialisation is limited by the extent of the market. The larger the market, the easier capital accumulation becomes if there is 1 Re. foreign trade provides the basis for import of foreign capital in LDC s.

There are some immediate static gains from trade which stem from Pareto optimum reallocation of resources in the trial of international trade. Consumption gain and production gain collectively lead to an improvement of social welfare. Consumption gain accrues to the economy when the same bundle of commodity is produced under free trade that were produced under autarky.

It is attributed to difference in relative price between pre- trade and post-trade situations. Production gain accrues to the economy over and above the consumption gain as a result of the shift of the production point due to difference between pre-trade and post-trade relative commodity prices. Now we shall illustrate the point diagrammatically.

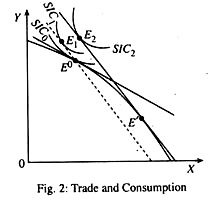

An autarky price equilibrium occurs at E0 where PPF touches SIC0. When trade opens up, there is a separation between consumption point and production point. The economy produces at E’ and consumes at E2. To isolate the consumption gain, let us assume that the production point is frozen at E0 but the economy will benefit from trade. It consumption point will move from E0 to E1, i.e., the economy will shift from SIC0 to S/C, which represents consumption gain. The production gain is represented by the movement fromE1 to E2 as a result of the change of production pattern from E0 to E2.

Corden’s Analysis:

The comparative cost doctrine emphasises the efficiency gains of trade. Corden argues that efficiency gains gradually acquire a dynamic character and involve cumulative impact on a country’s growth potential.

According to him, a country participating in world trade experience five different and distinct effects:

(a) Impact effect

(b) Capital accumulation effect

(c) Substitution effect

(d) Income distribution effect

(e) Factor weight effect.

These effects are all cumulative and intensify the increase in real income over time as trade breaks open. One important potential gain from trade is the provision of an outlet for a country’s surplus commodities [Export] which would otherwise go unsold representing a waste of resources-Trade Prides an outlet for an underdeveloped country with huge amount of unemployed natural resources and abundant unemployed or semi-employed labour to be utilised gainfully to produce an output even and above the domestic requirement which can then be exchanged for other scarce goods.

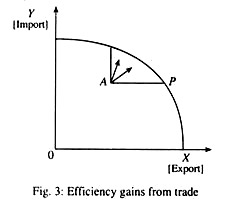

This is the so-called vent for surplus. In the vent for surplus theory, the economy has surplus productive capacity which implies an inelastic domestic demand for an exportable commodity and/or a considerable degree of immobility internally and specialise use of resources. Fig. 3 will show that trade will lead to an increase in the production of export sector without reducing the production of for the import sector.

The shift from A (pre-trade situation) to point P (post-trade situation) clearly shows the fact that trade has augmented the production of commodity X but the production of commodity Y has remained unaltered. Mynt has argued that the vent for surplus theory is a much more plausible theory than the comparative cost doctrine in explaining the rapid expansion of export production in most part of the developing world in the 19th century.

Mynt observed that, when parts of Africa and Asia came under European colonisation, the consequent expansion of their international trade enabled these areas to utilise their land or labour more intensively to produce tropical foodstuffs such as rice, cocoa and oil palm for exports.

According to J. S. Mill there are indirect effects of foreign trade which must be counted as benefits of high order. The most important indirect dynamic benefit is the tendency of every extension of the market to improve the process of production. Secondly, opening up of trade in a backward country gives its citizens exposure to new commodities and tempting them by easier acquisition of things which they had previously thought not attainable.

Thirdly, through the interaction with the developing countries, the LDCs come to know the art of development. Accumulation of knowledge has a great intellectual effect in trade which acts as the dynamic propelling force behind economic development.

According to Mill, the effect of foreign trade is nothing short of an industrial revolution, seeping to the hitherto underdeveloped regions in the trial of foreign trade. A number of export based modes of growth have been formulated to present a macro-dynamic view of how export performance determines the level of economic growth.

Here we can present different variants of the exports led growth:

(1) The initiation of economic development in an LDC requires the import of certain noncompetitive investment goods with negligible substitutability in the production process. The pace of industrialisation crucially depends on the availability of investment goods which in turn depends upon export performance of the country assuming that foreign exchange cannot be obtained either from foreign aid or redirected from consumption of imported finished product

(2) The issues connected with export-led growth can also be examined in the context of celebrated Lewis Model of Economic Development with unlimited supply of labour. We can visualize a traditional sector and an enclave export sector in an LDC, drawn labour from the traditional sector.

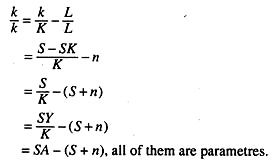

We can present a simple model to examine the role of growth in export in the determination of the overall rate of economic growth. Let us assume the entire wage is spent on consumption and saving comes from profit. The rate of growth is proportional inversely to the real wage and directly to the propensity to save and in product-efficiency of the economy.

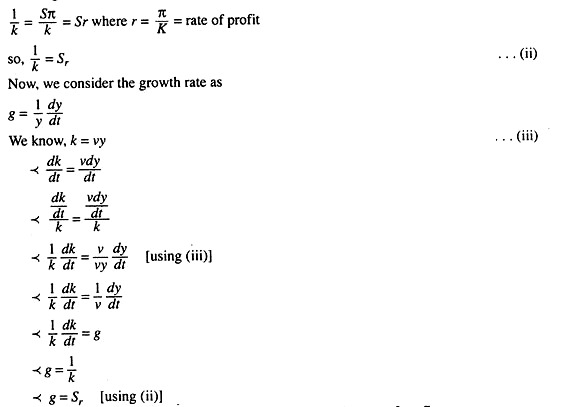

Now let us establish the direct relationship between the rate of growth and the rate of profit.

Here, y = wL + rk; where w = real wage held constant, and r = rate of profit

We know at equilibrium, I = S …(i)

Since saving is a function of profit,

We can write

S = Sπ where S = mps and π = total profit

... I = Sπ (using i)

Dividing both sides by k, we get

This proves that the rate of growth is directly related to the rate of profit.

Now we shall give diagrammatic representation:

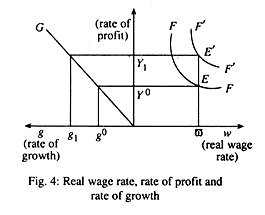

The right side shows the inverse relationship between rate of profit and real wage rate. Left hand side shows the positive relationship between rate of growth and rate of profit. Here FF is the efficiency curve. Product efficiency in the economy is indicated by the height of the FF curve. Higher the FF curve more is the product efficiency.

Let us suppose the real wage rate to be fixed at ɷ. International trade enhances product efficiency curve from FF to F’F’ in Fig. 4. With the wage rate fixed at ɷ, there is an increase in the profit rate from r0 to r1 and a corresponding rise in growth rate from g0 to g1. In a LDC the real wage rate is very low and, therefore, the country specialises in production process. Capital accumulation by playing back of profit in labour-intensive commodities can eventually lead to a rise in real wages, higher capital intensity and more sophisticated technology.

(3) The term ‘staple’ designates a raw material or a resource intensive commodity occupying a dominant position in the country’s economy. The staple theory postulates that with the discovery of a primary product in which a country has a comparative advantage, there is an expansion of a resource used export commodity, which induces higher rates of growth of aggregate and per capita income.

The export of a primary product also has the effect in the rest of the economy through diminishing underemployment, inducing a higher rate of domestic saving and investment, attracting an inflow of factor inputs into the expanding export sector and establishing linkage with other sectors of the economy.

Albert O. Hirschman coined the phrase ‘backward linkage’ for the situation in which the growth of one industry (such as textiles) stimulates domestic production of an upstream input (such as cotton or dye stuffs). Backward linkages are particularly effective when the using industry becomes so large that supplying industries can achieve economies of scale of their own, become more competitive in domestic or even export markets.

Expanded production of primary products also can stimulate forward linkages by making lower cost primary goods available as inputs into other industries. Consumption linkages develop indirectly as the higher income earned from primary product exports leads to increased demand for a wide range of consumption.

Infrastructure linkages arise when the provision of overhead capital—roads railroads, power, water, telecommunications—for the export industry lower costs and opens new production opportunities for other industries.

Primary export sectors also may stimulate human capital linkages through the development of local entrepreneurs and skilled labourers. The best case for petroleum, mining, and some traditional agricultural crops is the fiscal linkage.

The Relevance of the Solow Model:

Solow growth model is popularly known as Neo-classical exogenous growth model. Economy is a full employment economy and saving determines investment. The single most factor leading to growth is Exogenous Technological Progress. If technological progress is absent, then there is no growth.

The neo-classical economist of the 1950s and 60s recognised that technological improvement provide an escape from diminishing returns. Most reflect purposeful ac- Si research and development, since the amount of resources devoted to development depends on economic condition, the evolution of technology also depends on

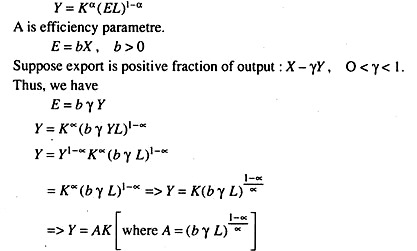

We shall now discuss Solow model with technological progress. We introduce labour augmenting technological progress.

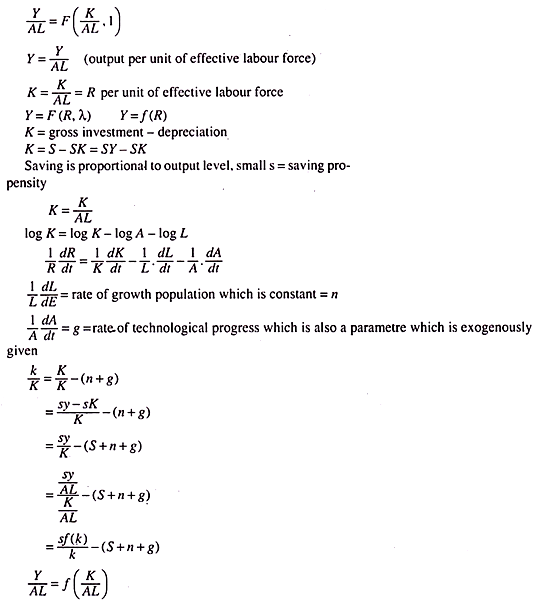

Y = F (K, AL), A is an efficiency parameter, growth of A is actually exogenous. It improves productivity of labour. Hence AL: effective labour force. Here function obeys CRS.

Now we shall discuss endogenous growth with production function as Y = AK K is a comprehensive category which also includes human capital. In Solow model, growth is due to Abut in endogenous model, A is fixed and then we show if growth exists or not

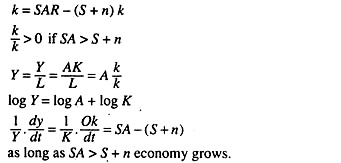

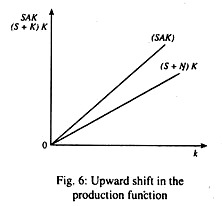

We shall move forward studying arguments by Baldwin and Majumder. Baldwin suggests that increase in real per capita income due to trade is an upward shift of the production function. His arguments have been modified by Majumder. He argues that developing countries import in goods and relative price of capital goods falls one trade opens

up.

This reduces cost of depreciation. Export requires specialisation which in turn promotes learning and innovation. In other words, there is ‘learning by exporting’. Export generates positive technological externality. We construct a simple model of endogenous growth to explain causal relation between trade and growth.

Let the production function be Cobb-Douglas type with CRS.

Exporting makes production functions behave as if it is AK type and, hence, all have endogenous growth.

We now consider some of the adverse effects of trade which can wipe out the beneficial ones:

(i) Nurkse argues that external forces determine the export performance of a developed country. Trade can no longer operate as an engine of growth in the 20th century because of the easy availability of substitutes of primary commodities which were the prime exports of a LDC to a developed country.

(ii) Levon is attributes the problem of trade as a faltering engine of growth to a general reduction in the rates of growth of income and expenditure in the DCs.

(iii) Even the neoclassical economists point out the possibility of immeserising growth in the wake of technological progress in an open economy.

(iv) P. S. hypothesis of TOT (terms of trade)—a structuralist approach.

(v) Dependency theory as the Neo-Marxist critique of trade.

Raul Prebisch generalized the empirical claim into the assertion that a LR decline in the terms of trade of developing countries is an essential consequence of growth and trade between the North and The south or the centre or the periphery.

Singer contends that opening up of LDCs to foreign trade and investment has tended to inhibit the development. This trade and investment have diverted the LDCs into types of activities offering less scope for technical progress and general and external economies.

It also leads to deterioration of the TOT by the operation of Engle’s Law. The views of Prebisch and Singer regarding secular deterioration of term of trade, however, face severe criticisms. Britain’s TOT should not be treated as the inverse of TOT of the LDCs. The TOT does not always take into account the quality of product and many more. Moreover the thesis has been vindicated by several data published by UWCTAD.

The important question is whether there should be free trade and not whether there should be trade. Those who question the assumption of comparative cost model express the view that the efficiency gained from free trade are unlikely to offset the tendency in a free market for the comparative position of the developing countries to deteriorate vis-a-vis the developed countries.

The success story of the Asian countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore in the field of export have added new dimension to the analysis of relation between trade and development. The experiences of these countries do demonstrate the potential of exports and labour-intensive production.

The international trading system has enhanced competition and nurtured what Joseph Schumpeter a number of decades ago called ‘creative destruction’, the continuous scrapping of old technologies to make way for the new.