Let us make an in-depth of the Stabilisation Policies. After reading this article you will learn about: 1. Subject-Matter of Stabilisation Policies 2. Monetary Shocks to Aggregate Demand 3. Shock to Aggregate Supply 4. Two Options.

Subject-Matter of Stabilisation Policies:

For reducing the severity of business cycles stabilisation policies are to be adopted.

These of two types — monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Such policies dampen the business cycle by keeping output and employment as close to their natural rates as possible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here we restrict ourselves to monetary policy which has a powerful impact on aggregate demand. In the next and subsequent chapters, in the context of Keynesian and post-Keynesian models, we shall examine how fiscal policy might respond to shocks.

Monetary Shocks to Aggregate Demand:

An example of monetary shock to aggregate demand is the growing use of credit cards to make transactions. This has reduced the demand for money and increased the velocity of money because velocity (V) is the reciprocal of the money demand parameter (k).

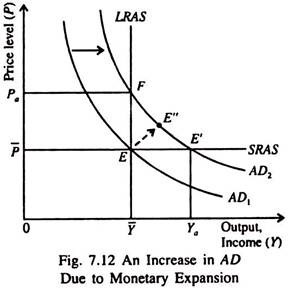

An increase in V, money supply remaining constant has caused nominal spending to rise and the aggregate demand curve to shift from AD1 to AD2 in Fig. 7.12. In the short run output rises from Y̅ to Ya. There is an economic boom. At the original prices, firms are able to sell

more. So they produce more by hiring more workers and making more effective use of their plant and equipment.

With the passage of time the high level of AD pushes up wages and prices. As the price level goes up, the quantity of output demanded falls and the economy gradually approaches its natural rate of production. But during the transition to the higher price level Pa the economy’s output is higher than the natural rate, as is indicated by point E”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For dampening the boom the central bank can keep output closer to the natural rate by reducing the money supply so as to offset the increase in velocity. Offsetting the increase in velocity is equivalent to stabilising aggregate demand. Thus by making appropriate use of monetary policy the central bank can reduce or even eliminate the impact of increasing demand on output and employment.

Shock to Aggregate Supply:

Supply depends mainly on cost of production. So anything which changes the cost of production and thus the prices of goods and services firms sell is called a supply shock, which can also cause business cycles. Supply shocks are also called price shocks.

Examples of adverse supply shocks are oil price hike, or strike in a major industry or a crop failure or an increase in the cost of environmental protection which raises total costs and prices. Technological progress, or a fall in the price of a major input or a bumper crop is an example of a favourable supply shock.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

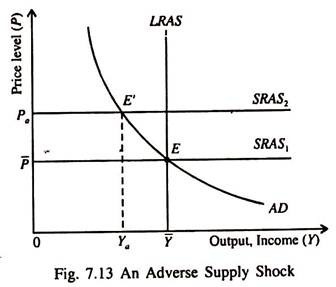

Fig. 7.13 shows that an adverse supply shock shifts the SRAS curve upward from SRAS1 to SRAS2. As a result the economy moves to the left along the same AD curve from E to E’. This problem, faced by most modern mixed economies, is known as stagflation — the coexistence of inflation and unemployment in a stagnant economy where output itself is at a low level due to rise in costs and prices.

Stagflation refers to a situation in which rise in prices coexists with falling output.

Ultimately, the economy returns from E’ to E. This means that as prices fall, output returns to its natural rate (Y̅). However, a wrongly directed monetary policy can itself be a cause of business cycles or a source of shocks to the economy.

Two Options:

For controlling demand in a situation of adverse supply shock, a policymaker has two options. The first option, as shown in Fig. 7.13, is to hold AD constant in which case output and employment are lower than their natural rate. Ultimately prices fall to the original level to restore full employment (as shown by point E). But the cost of this adjustment is a painful recession.

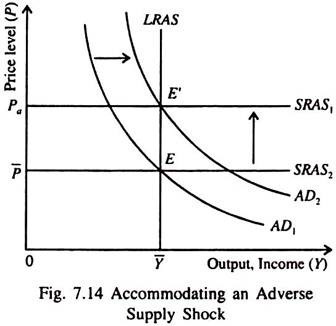

The second alternative is to expand AD to bring actual output and employment back to the natural rate as quickly as possible, as shown in Fig. 7.14. If the increase in AD coincides with the shock to AS the economy moves quickly from point E to E’.

This is how the central bank accommodates the supply shock. However, in this case the price level is permanently higher (Pa > P̅). It is not possible to achieve both the goals at the same time — full (high) employment and price stability.