In this article we will discuss about economic dualism and its characteristics.

The concept of economic dualism was first introduced by J. H. Boeke in 1953 in the context of the dual economy and dual society of Indonesia.

The term was used to refer to various asymmetries of production and organisation that exist in developing countries. Boeke first used the term to represent an economy and a society divided between the traditional sectors and the modern, capitalist sectors in which the Dutch colonialists operated.

According to I. Little, “an economy is dualistic when a significant part of it operates under a paternalist or quasi-feudalist regime, while another significant part operates under a system of wage employment—which may be capitalist or socialist.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There is both production asymmetry and organisational asymmetry in dual economies. The former implies that capital is not used at all in agriculture and land is not used at all in industry. The latter implies that even when returns to labour are equalised across the sectors by labour mobility, it is not the marginal products of labour in the two sectors which are so equalised.

Most LDCs have a colonial heritage. For example, India was under, the British rule for more than two centuries and it inherited a colonial structure at the time of Independence. It is often felt that the heritage of colonialism is partly responsible for the present-day backwardness and underdevelopment in LDCs like India.

The colonial era before World War II created the problem of economic dualism which implies the coexistence of traditional and modern sectors with the same economy or region. Colonialism brought in its wake enclaves of modernised sector the population was literate, worked for wages or engaged in commerce and have learned how to use modern technology such as railroads, motor cars, electric power and simple machines.

By contrast, in the traditional sector, the population was largely illiterate and engaged in subsistence agriculture. These were not used to wage labour (as in share-cropping) and accustomed to traditional methods of production and pre-industrial technology.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In agriculture, for instance, production has been carried out for decades with a pair of bullocks and a plough. The contrast was not only between urban and rural economies, but also between the beginnings of an industrial society and an existing pre-industrial one.

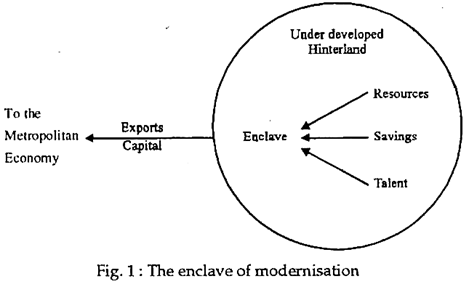

The colonial era led to the emergence of enclaves modernisation. These are modernised economic sectors — usually the beginnings of an industrial society — that exist within a traditional, usually pre-industrial, economic region. Within the less developed country the economic enclave draws resources, savings, and talented people out of the hinterland, making it less able to improve its economic base. See Fig. 1 which is self-explanatory.

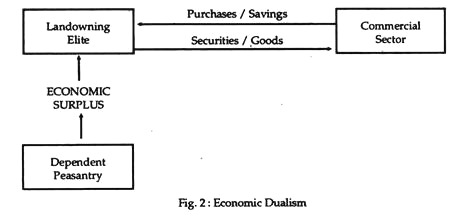

There appeared another type of dualism outside the modernised enclave. As described by D. Fusfeld: “the hinterland not only had a pre-industrial technology and peasant agriculture, it also had a different social and economic structure. The pattern was feudal, in the sense of a landowning aristocracy with a dependent peasantry.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such feudal economic structure was found in wide areas of Latin America and South-east Asia and exhibited the following common features:

1. A large portion of the land was owned by a few rich landlords.

2. Diverse economic relationships enabled the landlords to appropriate the surplus above subsistence level produced by a large number of small farmers and landless workers.

3. The peasantry was tied to the land due to age-old debt burden, force, and absence of alternative employment opportunities outside agriculture.

4. Population explosion created a surplus labour supply at a subsistence wage in both rural and urban areas.

5. The agricultural surplus appropriated by the landlords was converted into cash by sale of exports on world markets.

6. The income derived from exports helped support a commercial, urbanised sector in the poor country that was devoted largely to meeting the needs of the land-owing class, the upper middle class and the governments (at different levels).

Economic dualism is the result of the constellation of all these forces. All these result in dualism within the underdeveloped hinterland itself: “a poor and backward rural peasantry existing side by side with the luxury of the landed families, while the commercial cities were capitalist islands in a non-capitalist world”. The basic economic relationship are shown in Fig.2.

In short, a dualism exists in an LDC like India “when the hinterland surrounding an enclave of modernisation not only has a pre-industrial technology and peasant agriculture but also has a different social and economic structure.”