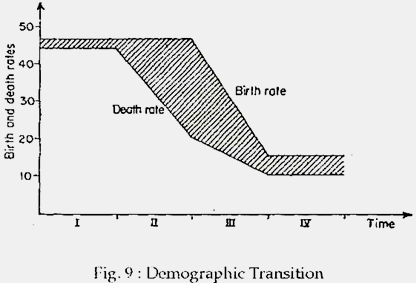

The demographic transition is “the name given to the shift from stable population at high birth and death rates to one at low birth and death rates”. A simplified version of those changes is shown in Figure 9. Increase in the rate of population growth is solely caused by the fall in the death rate. A constant birth rate and a declining death rate are sufficient to account for population growth rates of a high as 3% per annum as experienced by a number of countries.

In the last century, declines in death rates in Europe and the United States were associated with increases in income. Improvement in health care were paid for by individuals and by the public treasury out of incomes made higher by economy-wide changes in productivity. Due to this connection, various models of economic and demographic change have made death rates depend on income. Two of the most well-known are Harvey Leibenstein and Richard R. Nelson.

Kindleberger has shown that lower death rates no longer depend so closely on increases in national income. The discovery of very low cost technology to reduce disease and death (e.g., spraying DDT for malaria) and opening international assistance in this regard imply that the death rate can fall very rapidly in poor countries without a previous or simultaneous rise in per capita incomes.

The vertical distance between birth and death rates Fig. 9 shows the speed with which population grows. It is greatest when a society finds itself between stages II and III. Birth rates begin to decline, and the rate of decrease in death rates slows as time goes on.

For obvious reasons, changes in birth rates are correlated with increases in urbanisation, industrialisation, educational attainment, and emancipation of womenfolk as well as sharply lower costs of effective and convenient methods of birth control.

Once again, historical statistics indicate a correlation present between higher incomes and lower birth rates. But, in countries where urbanisation has not led to generally higher incomes and where contraceptive technology has changed radically, the link between incomes and human fertility is a more flexible one now.

According to Coale and Hoover, one result of the looser connection between per capita incomes and vital rates is that the demographic transition occurs more swiftly now than it did in currently affluent countries. Little evidence which is available indicates that birth-rate declines have similarly accelerated.

Again, some of the results of rapid population growth that have the most profound effect on economic development are those associated with changes in the age structure. When death rates fall, they fall most rapidly among infants — those children who are less than one year old.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The figure above shows the transition from a stable population at high birth and death rates to one at low rates.

Four stages in the transition may be characterised as follows:

I. Birth and death rates both high. Reproduction is largely unchecked, although it does not reach the biological maximum. Death rates vary widely from year to year. Bad harvests and high grain prices lead to famine and lowered resistance to disease. Epidemics then complete the cycle started by malnutrition and poor health in general. The figure smooth’s these year-to- year fluctuations, showing only averages for the two vital rates.

II. Death rates fall as expenditures for health are increased and as scientific discovery permits lives to be saved. At the same time, the birth rate continues at its previous level. As the two rates diverge, the rate of population growth increases.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

III. The death rate continues to fall although at slower speed as diminishing returns to further expenditures on health are encountered. The birth rate now falls, too, reflecting a combination of forces including urbanisation, education, and more effective contraceptive technology.

IV. Both birth and death rates level off. Further declines in the death rate are increasingly difficult (i.e., expensive) to achieve. Birth rates reflect new desires for smaller families as well as other demographic and economic forces. The rate of population growth is once again as it was in stage I, close to zero.

In the various countries that have undergone this transition, the stages have not been of equal length, nor have birth and death rates changed with the smoothness shown in the diagram.

The vital rates (birth and death rates shown on the vertical axis) are denominated in rates per 1,000, rather than in the more familiar percentage terms. Thus, for example, birth rates of 45 per 1,000 and death rates of 15 per 1,000 lead to rate of population growth of 30 per 1,000 or 3%.