The Liquidity Preference Theory was propounded by the Late Lord J. M. Keynes.

According to this theory, the rate of interest is the payment for parting with liquidity.

Liquidity refers to the convenience of holding cash. Everyone in this world likes to have money with him for a number of purposes. This constitutes his demand for money to hold.

The sum-total of all individual demands forms the demand for money for the economy. On the other hand, we have got a supply of money consisting of coins plus bank notes plus demand deposits with banks. The demand and supply of money, between themselves, determine the rate of interest.

Motives for Liquidity:

Money may be demanded to satisfy a number of motives.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are:

(i) Transactions Motive:

We get income only periodically. We must keep some money with us till we receive income next, otherwise how can we carry on transactions? Transactions motive also includes business motive. It takes some time before the businessman can sell his product in the market. But he must pay wages to the workers, cost of raw material, etc., now. He must keep some cash for the purpose.

(ii) Precautionary Motive:

Everyone lays by something for a rainy day. Some money must be kept to meet unforeseen situations and emergencies.

(iii) Speculative Motive:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Future is uncertain. Rate of interest in the market continues changing. No one can guess what turn the change will take. But everybody hopes, and with confidence, that his guess is likely to be correct. It may or may not be so. Some money, therefore, is kept to speculate on these probable changes to earn profit.

Interest-rate Determination:

Money demanded for all these motives or purposes constitutes demand for money, or liquidity preference. Liquidity preference means how much cash people like to keep with them at a particular time. The higher the liquidity preference, given the supply of money, the higher will be the rate of interest; and vice versa. Further, given the liquidity preference, the larger the supply of money, the lower will be the rate of interest, and the smaller the supply of money, the higher the rate of interest.

According to Keynes, the demand for money, i.e., the liquidity preference, and supply of money determine the rate of interest. It is in fact the liquidity preference for speculative motive which along with the quantity of money determines the rate of interest.We have explained above the speculative demand for money. As for the supply of money, it is determined by the policies of the Government and the Central Bank of the country. The total supply of money consists of coins plus notes plus demand deposits with banks.

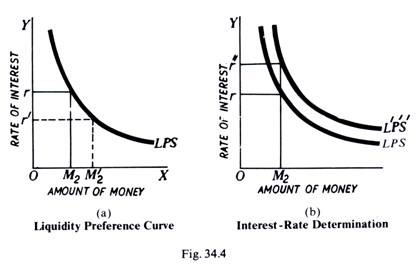

We see, thus, that according to liquidity preference theory, the rate of interest is purely a monetary phenomenon. Productivity of capital has very little, though indirect, say in determining the rate of interest. How the rate of interest is determined by the equilibrium between the liquidity preference for speculative motive and the supply of money is shown in Fig. 34.4.

In part (a) of the figure, LPS is the cur of liquidity preference for speculative motive. In other words, LPS curve shows the demand for money for speculative motive. To begin with, OM2 is the quantity of money available for satisfying liquidity preference for speculative motive. Rate of interest will be determined where the speculative demand for money is in balance with, or equal to, the (fixed) supply of money OM.2It is clear from the figure that speculative demand for money is equal to OM2quantity of money at or rate of interest. Hence or is the equilibrium rate of interest.

Assuming no change in expectations, an increase in the quantity of money (via open-market operations) for the speculative motive will lower the rate of interest. In part (a) of the figure, when the quantity of money increases from OM1 to OM2, the rate of interest falls from Or to Or’, because the new quantity of money OM’; is in balance with the speculative demand for money at Or’ rate of interest. In this case, we move down the LPS curve. Thus, given the schedule or curve of liquidity preference for speculative motive, an increase in the quantity of money brings down the rate of interest.

It is worth mentioning that shifts in liquidity preference schedule or curve can be caused by many other factors which affect expectations and might take place independently of changes in the quantity of money by the Central Bank. Shifts in the liquidity preference curve may be either downward or upward, depending on the way in which the public interprets a change in events.

If some change in events leads the people on balance to expect a higher rate of interest in the future than they had previously anticipated, the liquidity preference for speculative motive will increase, which will bring about an upward shift in the curve of liquidity preference for speculative motive and will raise the rate of interest.

In part (b) of Fig. 34.3, assuming that the quantity of money remains unchanged at OM2, with the rise of the liquidity preference curve from LPS to L’P’S’, the rate of interest rises from Or to Or”, because at Or”, the new speculative demand for money is in equilibrium with the supply of money OM2. It is worth noting that when the liquidity preference speculative motive rises from LPS to L’P’S’, the amount of money hoarded does not rise; it remains as OM; as before. Only the rate of interest rises from Or to Or” to equilibrate the new liquidity preference for speculative motive with the available quantity of money OM 2.

Thus, we see that Keynes explained interest in terms of purely monetary forces and not in terms of real forces like productivity of capital and thrift, which formed the foundation-stones of both classical and loanable fund theories. According to him, demand for money for speculative motive together with the supply of money determines the rate of interest.

Moreover, according to Keynes, interest is not a reward for saving or thriftiness or waiting, but for parting with liquidity. Keynes asserted that it is not the rate of interest which equalises saving and investment, but this equality is brought about through changes in the level of incomes.

Criticism:

Keynes’s theory, too, has come in for considerable criticism:

(i) Firstly, it has been pointed out that the rate of interest is not a purely monetary phenomenon. Real forces like productivity of capital and thriftiness also play an imp i.ant role in the determination of the rate of interest.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Keynes makes the rate of interest independent of the demand for investment funds. In fact, it is not so independent. The cash-balances of the businessmen are largely influenced by their demand for savings for capital investment. The demand for capital investment depends upon the marginal revenue productivity of capital. Therefore, the rate of interest is not determined independently of the marginal productivity of capital or marginal efficiency of capital, as Keynes calls it.

(iii) Liquidity preference is not the only factor governing the rate of interest. There are several other factors which influence the rate of interest by affecting the demand for and supply of investable funds.

(iv) This theory does not explain the existence of different rate of interest prevailing in the market at the same time.

(v) Keynes ignores saving or waiting as a source or means of investible funds. To part with liquidity without there being any saving is meaningless.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(vi) The Keynesian theory explains interest in the short run only. It gives no clue to the rates of interest in the long run.

(vii) Finally, exactly the same criticism applies to Keynesian theory itself on the basis of which Keynes rejected the classical and loanable funds theories. Keynes’s theory of interest, like the classical and the loanable funds theories, is indeterminate.

According to Keynes, the rate of interest is determined by the speculative demand for money and the supply of money available for satisfying speculative demand. Given the total money supply, we cannot know how much money will be available to satisfy the speculative demand for money unless we know how much the transactions demand for money is; and we cannot know the transactions demand for money unless we first know the level of income. Thus, the Keynesian theory, like the classical, is indeterminate.

“In the Keynesian case the supply and demand for money schedules cannot give the rate of interest unless we already know the income level; in the classical case the demand and supply schedules for savings offer no solution until the income is known. Precisely the same is true of loanable-funds theory. Keynes’s criticism of the classical and loanable-funds theories applies equally to his own theory.”—Hansen.