One of the major aspects of international trading relations during the post-war period has been the development of regional trade grouping or blocks, primarily in the form of customs unions.

Customs unions are by definition discriminatory. They mean a lowering of tariffs within the union and an establishing of a joint outer tariff wall. They combine free trade with protection.

Regional trade grouping or economic integration can take several forms representing different degrees of integration namely, free trade area, and customs union, and common market, economic union and complete economic integration.

A free trade area abolishes or decreases tariffs and other trade barriers within the constituent countries but each member country can impose its own tariffs on imports from non-members. When a free trade area agrees to have common tariffs on imports from non- members, then it is a customs union. When a customs union reaches agreement on removal of factor immobility within the union, then it is a common market.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When a common market reaches agreement on coordination of national economic policies of the members, then it is an economic union. Finally, the complete economic integration involves the unification of monetary, fiscal, social and counter cyclical policies and the setting up of a supra-national authority whose decisions are binding for the member countries.

In tariff theory, there are two types of discrimination, namely, the commodity discrimination and the country discrimination. The commodity discrimination is one where different tariff rates are applied to different commodities and the country discrimination is one where different tariff rates are applied to the same commodity according to its country of origin. The customs union theory deals with problems raised by the latter type of discrimination.

According to R.G. Lipsey, “The theory of customs unions may be defined as that branch of tariff theory which deals with the effects of geographically discriminatory changes in trade barriers”. The theoretical considerations which we are concerned here apply to customs unions, a grouping which we have defined in terms of its tariff policy.

The theory has being confined mainly to a study of the effects of customs union on welfare gains and losses which may arise from a number of different sources:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) The specialization of production according to comparative advantage which is the basis of the classical case for gains from trade;

(ii) Economies of scale;

(iii) Changes in the terms of trade;

(iv) Forced changes in efficiency due to increased foreign competition and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(v) A change in the rate of economic growth.

The conclusion of the earliest customs union theory may be summarized as follows. In the beginning customs unions have been viewed favourably. The reasoning was free trade maximizes world welfare; a customs union reduces tariffs and is therefore a movement towards free trade; a customs union will, therefore, increase world welfare even if it does not lead to a world-welfare maximization.

In his pioneering study, the Customs Union Issues, Jacob Viner showed this argument to be incorrect. He introduced the new familiar concepts of “trade creations” and “trade diversion”.

Trade Creation and trade diversion:

Let us discuss the concepts of trade creation and trade diversion through the following example.

Production cost of commodity (X) in three countries.

Assume that the transport costs among the countries are negligible and assume that each country can produce good (X) at a constant cost. That is, assume that the prices indicated in the table are constant regardless of the level of output.

If country A has a tariff of 100% percent on (X), there will be no imports of the good, but the domestic producers will dominate the home market. If A forms a customs union with either country (IS) or country (C), she will be better off; if the union is with (IS) she will get a unit of commodity (X) at an opportunity cost of Rs. 40 worth of exports instead of at the cost of Rs. 50 worth of other goods entailed by domestic production. This is an example of “trade creation”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If (A) has been levying a somewhat lower tariff, say 50% percent and it was non-discriminatory, she would have imported the good from the lower cost source, country (C), and the price in (A’s) home market would be Rs. 45. Let us now assume that (A) and (B) form a customs union. (A) will then instead, import (X) from (B), and the price in (A’s) market will be Rs. 40. Import will be switched from the low-cost supplier (C) to the high-cost supplier (B). This is an example “trade diversion” and since it entails a movement from lower to higher real cost sources of supply, it represents a movement from a more to less efficient allocation of resources. Trade diversion will lead to a lowering of welfare as it entails a less efficient allocation of resources.

This analysis assumes that the countries involved are fully employed both before and after the formation of the customs union. In this sense the analysis is of neoclassical type. This being the case, it is natural to let the analysis primarily be concerned with the effects on the allocation of resources and the welfare implications of the effects.

This kind of analysis gives rise to three possibilities. First, neither of the two countries forming the union produces the good in question. The customs union would then be of no significance as both countries would import the good from a third country just as they did before forming the union. Second, one of the countries, forming the union produces the good inefficiently that is, is not the lowest cost available source of supply.

The union partner would then import from the cheaper source and there would be a case of trade diversion. Third, both countries forming the customs union produce the good, in which case one of the countries will then be secured for the more efficient industry and there will be trade creation. This analysis suggests that if a customs union primarily leads to trade creation, it will lead to an increase in welfare; and if it primarily gives rise to trade diversion it will lead to a lowering in the world’s welfare. In this case, it will certainly lead to a lowering in the welfare of the third country (rest of the world). Whether it will also lead to a lowering in the welfare of the countries forming the customs union is less certain.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The implication of this analysis is that customs unions will lead to detrimental effects if the countries are complementary in the list of goods they produce. If, on the other hand, the group of commodities that both countries produce under tariff protection is large, the scope for positive welfare effects is large.

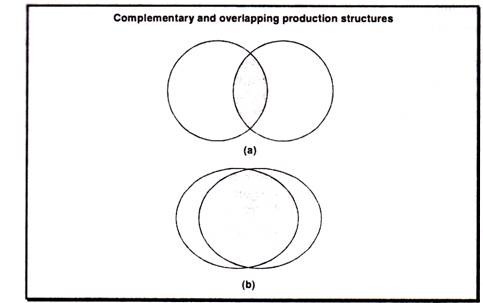

The following figures illustrate these facts:

Figure (A) illustrates a situation where the two countries are primarily complementary. The area where the two economies overlap shown by the shaded union of (A) and (B), is small. Figure (B) shows a situation where the two economies are primarily competitive. The area of overlapping production, shown by the shaded union of (A) and (B) is large. Intuitively one might think that an agricultural country ought to form an union with an industrial country. This is not the case.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Agricultural countries should form customs union with each other, and the industrial countries should form an union with another industrial country. The scope for trade creation is then largest and so is the scope for an improved allocation of resources and an increase in welfare. We can also observe that the larger the cost differentials between the countries in the union on the goods they produce before the union, the larger the scope for gains.

Viner assumed that:

(i) There are no possibilities of substitution in consumption;

(ii) That all price elasticity’s of demand are equal to zero;

(iii) On the supply side, the supposed the supply elasticities to be infinitely large, so that all products are produced under constant returns to scale.

It is easy to understand why Viner chose these assumptions. If goods are consumed in constant proportions irrespective of prices and if costs are constant, then the only interesting thing left to study is the shifts in production between countries as given by trade creation and trade diversion. The trade diversion for instance, will always cause a lowering of welfare.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

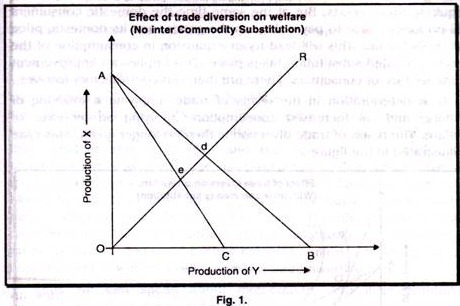

Country A is completely specialized in production good (X) and produces at point (A) on the X axis. It exchanges (X) for (Y) on the world market at the best terms of trade possible. They are given by the line AB. Consumers in the country consume the two goods in constant proportion given by the ray OR from the origin. The point of consumption is then at (d).

A now forms a customs union with C. This leads to trade diversion. Country A is still completely specialized in production (X) which it exchanges for (Y) from C. Because of the customs union, A’s terms of trade deteriorate. The new terms of trade are given by the line AC. The country still consumes along the ray OR and consumption now will be at point (e). This point is clearly inferior to (d) as it represents a smaller amount of both goods.

This analysis shows that, on the Vinerian assumption of no substitution in consumption, trade diversion will necessarily lower A s welfare. But Viner’s assumptions are very strong and quite unrealistic. A customs union will normally lead to a change in all relative prices. Then, substitution will take place. This is what would normally be expected. Now we will look into some of the effects that substitution in consumption might give rise to.

Inter-country and Inter-commodity Substitution:

If a country enters a customs union and trade diversion follows on some goods it means that the country will have to pay a higher price in acquiring these goods. But at the same time the domestic consumers will no longer have to pay a duty on the goods, and its domestic price will probably fall. This will lead to an expansion in consumption of the goods, provided substitution takes place. This implies an improvement in the welfare of consumers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are then two contradictory forces:

(i) A deterioration in the terms of trade, implying a lowering of welfare; and

(ii) Increased consumption, implying an increase of welfare.

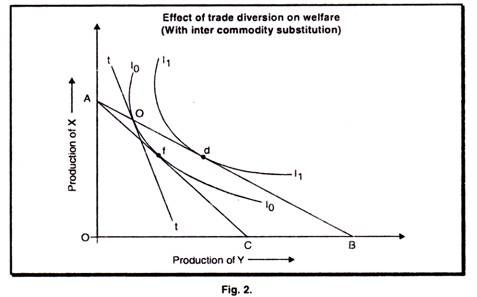

The result of trade diversion is then no longer given. This case is illustrated in the figure 2.

Country (A) is completely specialized in the production of good (X) and produces at point (A) on the X-axis. Before the union it imports good (Y) from the cheapest possible source country (B), at the terms of trade AB. If free trade were permitted, consumption would be at point (d) where an indifference curve 1, 1, is tangent to price line AB. Plow the country prefers to have a steep duty on (Y), and the domestic price ratio is indicated by price line (tt). The tariff leads to a fall in consumption of (Y) which is substituted by (X) and to a lowering in consumer’s welfare. The terms of trade AB are assumed not to have been affected by the tariff.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Country (A) now forms a customs union with (C). This leads to trade diversion and to a worsening of (A’s) terms of trade. The country will produce at (A) and exchanges (X) for (Y). The new terms of trade are given by line (AC). This need not necessarily lead to a lowering in welfare for consumers, because the price ratio (AC) will now be ruling in (A’s) domestic market and (Y) is now cheaper than at the tariff- inclusive price ratio (tt). (Y) will therefore be substituted for (X) in consumption and consumption will move to point (f). Point (f) is on the same indifference curve as (C). Hence consumers are as well off after the customs union as before.

This shows that a customs union, even though it leads to trade diversion, could result in consumers being as well off as before. If the deterioration in terms of trade had been less than what is shown by (AC) and the new price line had been somewhere in between AB and AC, the customs union would have led to an increase in consumers’ welfare and would have put them on a higher indifference curve than (IoIo). Then the customs union would have increased consumers’ welfare even though it was a trade diverting kind. This demonstrates that if substitution in consumption takes place, it implies that a customs union can lead to an improvement in welfare even if it is of a trade diverting nature.

Thus we can speak about inter-country and inter-commodity substitution. Inter-country substitution is Viner’s trade diversion and trade creation. Inter-commodity substitution is the usual substitution that takes place between commodities, both on the supply and the demand side, because of changes in relative prices. A customs union will give rise to both kinds of substitution. If both kinds are taken into account, the situation becomes more complex and the possibility of drawing inferences becomes more limited.

A customs union has both free trade side and a protectionist side. The welfare effects of a union depend on which is stronger. We have now seen some of the factors that are important when assessing the economic gains and losses of a customs union. The gains are primarily connected with trade creation, the losses with trade diversion. But how are these gains and losses to be measured? Here the height of the tariffs comes in as an important factor.

The Height of Tariffs and Tariff Removals:

In a competitive world the supply price of a good indicates the cost (marginal) to the producer and thus the opportunity cost, and the demand price indicates the utility of the good to the consumer. If no tariffs, taxes or other distortions exist, the supply price of a good will be the same as the demand price. If taxes or tariffs exist, this is no longer the use. Suppose there is a 50 percent tax on a product: if the cost of production of the good is Rs. 2, then the producer of the good will get Rs. 2 for it, but consumer will have to pay Rs. 3 for it.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since the producer is living in a competitive world, it means that the last unit of the product must be worth Rs. 2 to him that it must cost Rs. 2 worth of resources to produce. Similarly, since the consumer is willing to pay Rs. 3 for a unit of goods, it means that it must be worth Rs. 3 to him. A discrepancy in utility for producers and consumers thus exists, and it trade in the product could be increased, this would lead to an increase in welfare.

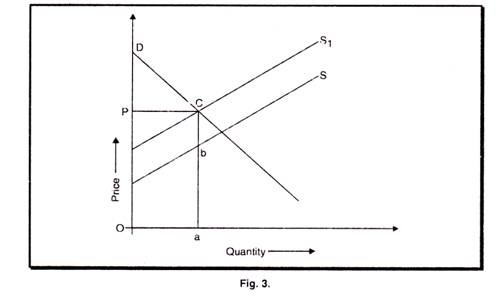

A tax or tariff has completely analogous effect in this respect, and we can illustrate the effect of a tariff in a geometric fashion.

A tariff, or a tax, can be thought of as shifting the supply curve to the left. The pre-tariff curve is (S) and the tariff-inclusive supply curve is (S1). Equilibrium is established at (C), with (p) being the price and Oa the quantity consumed. The tariff rate in the figure is Cb/ba percent, and the supply price differs from the demand price by this amount. An increase in trade of this good would, on the margin, mean an increase in welfare of an amount equal to (cb).

This type of analysis implies that the higher the initial tariffs between the countries forming the customs union, the larger the scope for gain. Conversely, the lower the tariffs with the outside world, the lower should be losses due to trade diversion.

When we take the heights of tariffs into account we can no longer try to estimate gains and losses by simply taking trade creation and trade diversion at face value. We also have to weigh, the values of trade created and diverted with the heights of the tariffs involved.

The Dynamic Effects:

So far, the whole discussion of the effects of customs unions has been in static terms. Many of the interesting influences around which controversy centres still, however, lie outside the formal analysis; for they are concerned with the effects of customs unions both upon constituent countries and upon the world at large, overtime.

These dynamic effects are not amenable to rigorous analysis and theory is not of much help in discussing them, but they are important, perhaps more important than the static concepts of trade creation and trade diversion. There is widespread disagreement about the significance and strengths of dynamic influences.

Four dynamic effects come up for attention in the literature.

They are:

(i) The stimulus imparted to countries in the union by competition;

(ii) The probable acceleration of technological change;

(iii) The stimulus given to investment; and

(iv) The economies of scale which union makes possible for industries in participant countries.

An important argument of a dynamic character is that a customs union will lead to enforced competition. This argument has been applied to the European Economic Community. As tariff fall away between union members, monopolies and cartels within individual countries become exposed to pressure in their domestic markets from firms elsewhere in the union.

Inefficient and un-enterprising firms and firms below optimum size are similarly exposed. The result will be a restructuring of industry for survival or for wider market penetration with beneficial effects on costs and prices. Scitovsky has argued that this competitive effect has been an important one in the European Economic Community.

A second view which favours customs unions is that they will speed economic growth, since the enlargement of the market will encourage innovation and technological change. As the market grows so the optimum size of firms will increase and additional resources be deployed into research and development. Whether this will result in a faster rate of innovation is of course problematic.

There is little empirical evidence to show that the rate of technical innovation in large firms exceeds that in small firms. The most we can say is that the potential for innovation is there and that wide markets and keen competition provide a favourable climate for it.

It may be expected that, within the union, investment will be stimulated by wider market opportunities, by changes in prices, and by increase of competition. The total impact upon investment is hard to estimate, since it will be compounded of a number of influences, some favourable, some less so. Besides domestic investment, union countries may experience a growth in investment from abroad, foreign firms with plants already within the union may expand or regroup these to meet the new circumstances created by the union.

Other institutional aspects which could be important are those connected with increased factor movements and with rights to establish businesses within the union. Movements of labour and capital could increase the productivity of the factors in question and foster growth.

A greater freedom in establishment rights would perhaps lead not only to a greater personal freedom and increased well-being, but also to a faster spread of knowledge and thereby to faster growth. Factors such as these could be important.

It was widely argued during the period preceding the treaty of Rome that the growth of industry in the United States and the high per capita income in that country sprang in great part from the huge market which American industry has served and the economies of scale which this has made possible. Great would be the advantages for European industries when a market of millions of people was provided within the community.

Within the union, industrial specialization will take place that as a result unit costs will fall with full utilization of plant, long production runs and growing expertise of labour and management and that further economies will be made possible by scientifically planning and locating such costly basic industries as steel, base metals and power supply.

Some Practical Implications:

Let us summarize some of the main results of the theory of customs unions.

They are:

(i) When a union is formed both trade creation and trade diversion will take place. The higher the elasticities of demand and supply for the goods that will come into trade between union members after elimination of the tariff the more will be the trade creation.

(ii) The more the foreign trade of union members was with other union members before the union was formed, the more likely it is that the union will raise welfare.

(iii) The higher the pre-union tariffs between the members of the union, the greater will be the trade creation once the union is formed and the tariffs are removed.

(iv) The lower the level of the common tariff of a union the less trade diversion the union will cause.

(v) Trade creation and greater efficiency in resource use will result from a customs union between countries which are rivals in trade than between countries whose goods are complementary.

It would appear on theoretical grounds that the European Common Market, tightly integrated geographically as it is in the centre of the trading world, has a much stronger potential for reaping the advantages of union than have the other free-trade areas, particularly those in the developing world.