In this article we will discuss about the biological theory of population.

In modern times biologists and statisticians have made intensive studies of population growth and have attempted to find out the principles governing it. Two conclusions of this approach are of interest to economists. One relates to the nature of population growth and the other to the method of measuring it.

These are explained below:

In the words of A. J. Coale, one of the experts in population studies, “the demographic transition is a specific change in the reproductive behaviour of a population that is said to occur during the transformation of a society from a traditional to a highly modernised state. The postulated change is from near equality of birth and death rates at high levels to near equality of birth and death rates at low levels. In the pre-modern state women who survive to age 50 have borne a large number of children; in the fully modernised society women bear only a small number. In a traditional society high mortality rates imply a low average duration of life; in highly modernised societies low mortality rates permit a long average duration of life”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

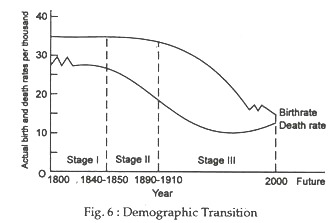

According to this theory, all developed countries have passed through three stages of modern economic history. Historical and statistical observations show that population does not always grow at a fast rate. The rate of growth of population growth is graphically charted it looks like the S- shaped curve known in mathematics as the Logistic Curve. This shows that population initially increases very slowly, then comparatively rapidly and finally becomes either stationary or declines.

These phenomena may be explained as follows:

i. Early Stage:

In the early stage of development of a country, there are obstacles to the growth of population like lack of security, lack of food, un-favourable social customs, etc. Therefore, population grows slowly. This situation is found in tribal communities and primitive civilisations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Intermediate Stage:

With development, these obstacles are removed and population grows rapidly during the intermediate stage of demographic transition. For example, among the Aryans in ancient India and in ancient U.S.A. in the 19th century the rate of population growth was high.

This stage has been termed as the stage of ‘Population Explosion’. The impact of this explosion in the overall economy of a country can be measured from the fact that it creates an imbalance in the economy. For a balanced adjustment of the economic instability, a period of transition is required and, hence, the theory is termed as the theory of demographic transition.

iii. Final Stage:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But, as soon as the community reaches an advanced stage of civilisation, the rate of growth becomes steady or declines. This situation is found in U. K., France, and other West European countries.

According to Malcom Gillis, “Despite the dramatic acceleration of change and foreshortening of the demographic eras, population growth has slowed in some parts of the world. The industrial countries have experienced a demographic transition”.

As Fig. 6 shows, initially these countries had both high birth and death rates (stage I), a pattern followed by a fall in the death rate (stage II). This, in turn, raised the rate of natural increase. After a few decades, this was followed by a drop in the death rate, which lowered natural increase to around 1% (stage III).

In the p re-industrial stage today’s developed countries had stable or very slow growing populations due to high birth rates and equally high death rates. This was stage I. This was followed by stage II when modernisation, associated with improved public health methods, better diets, higher incomes, etc., led to marked reduction in mortality that gradually raised life expectancy from under 40 years to over 60 years.

However, “the decline in death rates was not immediately accompanied by a decline in fertility. As a result, the growing divergence between high birth rates and falling death rates led to sharp increases in population growth compared to past centuries”. It is true to suggest that this intermediate stage marks the beginning of the demographic transition.

It implies the transition from stable or slow-growing populations first to rapidly increasing numbers and then to declining rates. Finally, an advanced country enters stage III of its population history when the forces and influences of modernisation and development caused the beginning of a fall in fertility; ultimately, the trend was toward zero population growth (ZPG), when falling birth rates converged with lower death rates.

The Transition of LDCs:

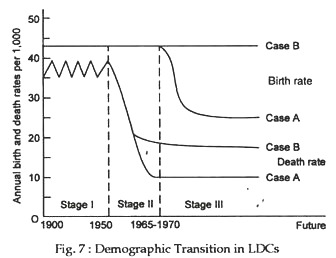

However, the population histories of contemporary LDCs are in sharp contrast with those of industrially advanced countries like that of Western Europe. In most LDCs the beginning of a demographic transition is clearly visible. Population histories in such countries, as Todaro has observed, follow diverse patterns.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Largely due to early marriage of women, birth rates in most LDCs today are considerably higher than they were in Western Europe before economic modernisation.

Due to early marriage of women two things happen:

(1) Prolongation of the child-bearing age, and

(2) More families for a given population size.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This trend began in the 1940s and got accelerated in the next two decades, viz., 1950s and 1960s. During these two decades stage II of the demographic transition occurred in most of the LDCs. Due to the application of modern medical and public health technologies (both domestic and imported) death rates began to fall more sharply than in the 19th century Europe.

The implication was simple — given their historically high birth rates over 40 per 1,000, many an LDC’s stage II demographic transition has been characterised by population growth rates well in excess of 2 – 2.5% per annum.

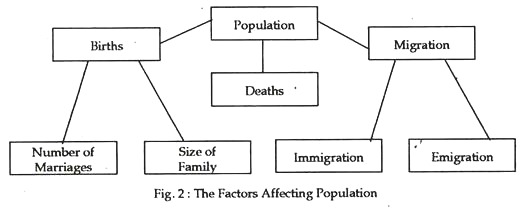

As for stage III, it is not possible to arrive at a clear trend. Instead it is possible to distinguish between two broad classes of LDCs, as Fig.2 shows.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In case A, (1) modern methods of death control and (2) rapid and widely distributed rises in levels of living have conjointly contributed to falling death rate to as low as 10 per 1,000 and birth rates to level between 20 to 30 per 1,000. Sri Lanka, South Korea, Costa Rica, China, Cuba, Thailand, Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic and the Philippines have already entered stage III—a period of sustained fertility decline.

By contrast, most LDCs fall into case B of Fig. 7. Most countries of Middle East, sub- Sahara Africa and some countries of Asia (like India) are still in stage II. Fig.7 shows that “after an initial period of rapid decline, death rates have failed to drop further, largely because of the persistence of widespread absolute poverty and low levels of living. Moreover, the continuance of high birth rates as a result of these low levels of living causes overall population growth rates to remain relatively high”.