Similarity between the Two Analyses:

Barring some economists like Dennis Robertson, W. E. Armstrong, F. H. Knight, it is now widely believed that indifference curve analysis makes a definite improvement upon the Marshallian cardinal utility analysis.

It has been asserted that whereas Marshallian utility analysis assumes ‘too much’, it explains ‘too little’, on the other hand, the indifference curve analysis explains more by taking fewer as well as less restrictive assumptions.

Though the two types of analyses are fundamentally different approaches to the study of consumer’s demand, they nonetheless, have some common points which are as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Both the analyses assume that the consumer is rational in the sense that he tries to maximize utility or satisfaction. The assumption of indifference curve analysis that the consumer tries to reach the highest possible indifference curve and thus seeks to maximize his level of satisfaction is similar to the assumption made in Marshallian utility analysis that the consumer attempts to maximize utility.

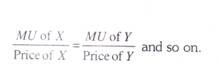

(b) In Marshallian utility analysis, condition of consumer’s equilibrium is that the marginal utilities of various goods are proportional to their prices. In other words, a consumer is in equilibrium when he is distributing his money income among various lines of expenditure in such a way that,

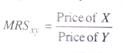

According to indifference curve analysis, consumer is in equilibrium when his marginal rate of substitution between the two goods is equal to the price ratio between them. That is.

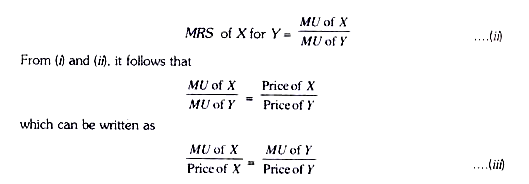

That the equality of the marginal rate of substitution with the price ratio is equivalent to the Marshallian condition that marginal utilities are proportional to their prices is shown below:

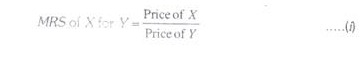

In equilibrium, according to indifference curve analysis:

But MRS of X for Vis defined as the ratio between the marginal utilities of the two goods. Therefore,

It is evident that:

(iii) is the same proportionality condition of consumer’s equilibrium as enunciated by Marshall.

(c) The third similarity between the two types of analysis is that some form of diminishing utility is assumed in each of them. In Hicksian indifference curve analysis, indifference curves are assumed to be convex to the origin. The convexity of the indifference curves implies that the marginal rate of substitution of X for Y diminishes as more and more of X is substituted for y. This principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution is equivalent to the Marshallian law of diminishing marginal utility.

(d) Another similarity between the two approaches is that both employ psychological or introspective method. In the introspective method, as has been seen already, we attribute a certain psychological feeling to the consumer by looking into and knowing from our own mind. In Marshallian analysis, observed law of demand is explained by the psychological law of diminishing marginal utility which is based upon introspection.

In Hicks-Alien indifference curve technique, indifference curves are usually obtained through psychological-introspective method. Though some attempts have been made recently by some economists to obtain indifference curves from the observed data of the consumer’s behaviour, but with limited success.

As things are, in the Hicks-Alien indifference curve analysis, indifference curves are derived through hypothetical experimentation. Thus, the method of indifference curve analysis is fundamentally psychological and introspective. “The basic methodological approach of Hicks- Alien is same as in the Marshallian marginal utility hypothesis: It is, that is to say, mainly, introspective”.

Superiority of Indifference Curve Analysis:

So far we have pointed out the similarities between the two types of analyses, we now turn to study the difference between the two and to show how far indifference curve analysis is superior to the Marshallian cardinal utility analysis.

1. Ordinal vs. Cardinal Measurability of Utility:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the first place, Marshall assumes utility to be cardinally measurable. In other words, he believes that utility is quantifiable, both in principle and in actual practice. According to this, the consumer is able to assign specific amounts to the utility obtained by him from the consumption of a certain amount of a good or a combination of goods. Further, these amounts of utility can be manipulated in the same manner as weights, lengths, heights, etc.

In other words, the utilities can be compared and added. Suppose, for instance, utility which a consumer gets from a unit of good A is equal to 15, and from a unit of good B equal to 45. We can then say that the consumer prefers B three times as strongly as A and the utility obtained by the consumer from the combination containing one unit of each good is equal to 60. Likewise, even the differences between the utilities obtained from various goods can be so compared as to enable the consumer to say A is preferred to B twice as much as C is preferred to D.

According to the critics, the Marshallian assumption of cardinal measurement of utility is very strong; he demands too much from the human mind. They assert that utility is a psychological feeling and the precision in measurement of utility assumed by Marshall is therefore unrealistic. Critics hold that the utility possesses only ordinal magnitude and cannot be expressed in quantitative terms.

According to the sponsors of the indifference curve analysis, utility is mere orderable and not quantitative. In other words, indifference curve technique assumes what is called ‘ordinal measurement of utility’. According to this, the consumer need not be able to assign specific amounts to the utility he derives from the consumption of a good or a combination of goods but he is capable of comparing the different utilities or satisfactions in the sense whether one level of satisfaction is equal to, lower than, or higher than another.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He cannot say by how much one level of satisfaction is higher or lower than another. That is why the indifference curves are generally labeled by the ordinal numbers such as I, II, III, IV, etc., showing successively higher levels of satisfaction. The advocates of indifference curve technique assert that for the purpose of explaining consumer’s behaviour and deriving the theorem of demand, it is quite sufficient to assume that the consumer is able to rank his preferences consistently.

It is obvious that the ordinal measurement of utility is a less severe assumption and sounds more realistic than Marshall’s cardinal measurement of utility. This shows that the indifference curve analysis of demand which is based upon the ordinal utility hypothesis is superior to Marshall’s cardinal utility analysis.

The superiority of indifference curve analysis is rather overwhelming since even by taking less severe assumption it is able to explain not only as much as Marshall’s cardinal theory but even more than that as far as demand theory is concerned.

2. Analysis of Demand without Assuming Constant Marginal Utility of Money:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another distinct improvement made by indifference curve technique is that unlike Marshall’s cardinal utility approach it explains consumer’s behaviour and derives demand theorem without the assumption of constant marginal utility of money. In indifference curve analysis, it is not necessary to assume constant marginal utility of money.

As has already been seen, Marshall assumed that the marginal utility of money remains constant when there occurs a change in the price of a good. The Marshallian demand analysis based upon constancy of marginal utility of money is not self-consistent. In other words, “the Marshallian demand theorem cannot genuinely be derived from the marginal utility hypothesis except in one commodity model, without contradicting the assumption of constant marginal utility of money”.

It means that “the constancy of marginal utility of money is incompatible with the proof of the demand theorem in a situation where the consumer has more than a single good to spread his expenditure on.” To overcome this difficulty in Marshallian utility analysis, if the assumption of constant marginal utility of money is abandoned, then money can no longer serve as a measuring rod of utility and we can no longer measure marginal utility of a commodity in units of money.

Thus, Marshall’s cardinal utility theory finds itself in a dilemma; if it adopts the assumption of constancy of marginal utility of money, as it actually does, it leads to contradiction and if it gives up the assumption of constancy of marginal utility of money, then utility is not measurable in terms of money and the whole analysis breaks down.

On the other hand, indifference curve technique using ordinal utility hypothesis can validly derive the demand theorem without the assumption of constant marginal utility of money. In fact, as we shall see below, the abandonment of the assumption of constant marginal utility of money enables the indifference curve analysis to enunciate a more general demand theorem.

3. Greater Insight into Price Effect:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The superiority of indifference curve analysis further lies in the fact that it makes greater insight into the effect of the price change on the demand for a good by distinguishing between income and substitution effects. The indifference technique splits up the price effect analytically into its two component parts substitution effect and income effect. The distinction between the income effect and the substitution effect of a price change enables us to gain better understanding of the effect of a price change on the demand for a good.

The amount demanded of a good generally rises as a result of the fall in its price due to two reasons. Firstly, real income rises as a result of the fall in price (income effect) and, secondly, the good whose price falls becomes relatively cheaper than others and therefore the consumer substitutes it for others (substitution effect). In indifference curve technique, income effect is separated from the substitution effect of the price change by the methods of ‘compensating variation in income’ and ‘equivalent variation in income’.

But Marshall by assuming constant marginal utility of money ignored the income effect of a price change. He failed to understand the composite character of the effect of a price change. Prof. Tapas Majumdar rightly remarks, “The assumption of constant marginal utility of money obscured Marshall’s insight into the truly composite character of the unduly simplified price-demand relationship”.

In this context, remarks made by J. R. Hicks are worth noting, “The distinction between direct and indirect effects of a price change is accordingly left by the cardinal theory as an empty box, which is crying out to be filled. But it can be filled. The really important thing which Slutsky discovered in 1915 and which Alien and I rediscovered in the nineteen thirties, is that content can be put into the distinction by tying it up with actual variations in income, so that the direct effect becomes the effect of the price change combined with a suitable variation in income, while the indirect effect is the effect of an income change.

Commenting on the improvement made by Hicks-Alien indifference curve approach over the Marshallian utility analysis. Prof. Tapas Majumdar says: “The efficiency and precision with which’ the Hicks-Alien approach can distinguish between the ‘income’ and ‘substitution’ effects of a price change really leaves the cardinalist argument in a very poor state indeed.

4. Enunciation of a more general and adequate ‘Demand Theorem”:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A distinct advantage the technique of dividing the effect of a price change into income and the substitution effects employed by the indifference curve analysis is that it enables us to enunciate a more general and a more inclusive theorem of demand than the Marshallian law of demand. In the case of most of the normal goods in this world, both the income effect and the substitution effect work in the same direction, that is to say, they tend to increase the amount demanded of a good when its price falls.

The income effect ensures that when the price of a good falls, the consumer buys more of it because he can now afford to buy more; the substitution effect ensures that he buys more of it because it has now become relatively cheaper and is, therefore, profitable to substitute it for others. This thus accounts for the inverse price-demand relationship (Marshallian law of demand) in the case of normal goods.

When a certain good is regarded by the consumer to be an inferior good, he will tend to reduce its consumption as a result of the increase in his income. Therefore, when the price of an inferior good falls, the income effect so produced would work in the opposite direction to that of the substitution effect. But so long as the inferior good in question does not claim a very large proportion of consumer’s total income, the income effect will not be strong enough to outstrip the substitution effect.

In such a case, therefore, the net effect of the fall in price of an inferior good will be to raise the amount demanded of the good. It follows that even for most of the inferior goods, the Marshallian law of demand holds good as much as for normal goods. But it is possible that there may be inferior goods for which the income effect of a change in price is larger in magnitude than the substitution effect. This is the case of Giffen goods for which the Marshallian law of demand does not hold good.

In such cases, the negative income effect outweighs the substitution effect so that the net effect of the fall in price of the good is the reduction in quantity demanded of it. Thus, amount demanded of a Giffen good varies directly with price.

It is clear from above that by breaking the price effect into income effect and substitution effect, the indifference curve analysis enables us to arrive at a general and a more inclusive theorem of demand in the following composite form:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) The demand for a commodity varies inversely with price when the income elasticity of demand for that commodity is nil or positive.

(b) The demand for a commodity varies inversely with price when the income elasticity is negative but the income effect of the price change is smaller than the substitution effect.

(c) The demand for a commodity varies directly with price when the income elasticity is negative and the income effect of the price change is larger than the substitution effect.

In the case of (a) and (b), the Marshallian law of demand holds while in (c) we have a Giffen-good case which is exception to the Marshallian law of demand. Marshall could not account for ‘Giffen Paradox’, Marshall was not able to provide explanation for ‘Giffen Paradox’ because by assuming constant marginal utility of money, he ignored the income effect of the price change. The indifference curve technique by distinguishing between the income and substitution effects of the price change can explain the Giffen-good case.

According to this, the Giffen paradox occurs in the case of an inferior good for which the negative income effect of the price change is so powerful that it outweighs the substitution effect, and hence when the price of a Giffen good falls, its quantity demanded also falls instead of rising. Thus, a great merit of Hicks-Alien indifference curve analysis is that it offers an explanation for the Giffen- good case, while Marshall failed to do so.

It is quite manifest from above that Hicks-Alien indifference curve analysis, though based upon fewer as well as less severe assumptions, yet it enables us to enunciate a more general demand theorem covering the Giffen-good case. To quote Prof. Tapas Majumdar on this point. “The ordinal theory succeeds in stating the relationship between a given change in the price of a commodity and its demand in a composite form distinguishing between the income and the substitution effects which fills in a genuine gap in the Marshallian statement of ‘law of demand’.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Implications of a Price Change in terms of Income and Welfare Increments:

Another distinct improvement of Hicks-Allen ordinal theory is that, through it, the welfare consequences of a change in price can be translated into those of a change in income. As seen above, a fall in the price of a good enables the consumer to shift from a lower to a higher level of welfare (or satisfaction). Likewise, a rise in the price of the good would cause the consumer to shift down to a lower indifference curve and therefore to a lower level of welfare.

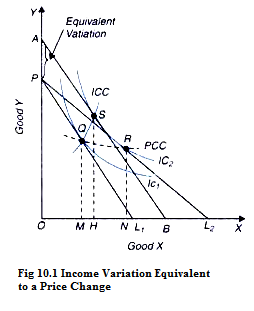

This means that a fall in price of a good causes a change in consumer’s welfare exactly as the rise in income would do. In other words, the consumer can be thought of reaching higher level of welfare through an equivalent rise in income rather than the fall in price of a good. In Fig. 10.1, with the fall in price of good X from PL1 to PL2 the consumer shifts from indifference curve IC1 to the indifference curve IC2 showing an increase in his level of welfare.

The discovery of a suitable change in income equivalent in terms of welfare to a given change in price has enabled Hicks to extend Marshall’s concept of consumer’s surplus. Marshall’s concept of consumer’s surplus was based upon the assumption that utility was cardinally measurable and also that the marginal utility of money remained constant when the price of a good is changed.

Thus, in Figure 10.1, equivalent variation PA is surplus income or gain in welfare accrued to the consumer as a result of fall in price of a commodity. Hicks has freed the concept of consumer’s surplus from these dubious assumptions and by using ordinal utility hypothesis along with the discovery that the welfare effect of a price change can be translated into a suitable change in income, he has been able to rehabilitate and extend the concept of consumer’s surplus.

6. Hypothesis of Independent Utilities Given Up:

Marshall’s cardinal utility analysis is based upon the hypothesis of independent utilities. This means that the utility which the consumer derives from any commodity is a function of the quantity of that commodity and of that commodity alone. In other words, the utility obtained by the consumer from a commodity is independent of that derived from any other. By assuming independent utilities, Marshall completely bypassed the relation of substitution and complementarity between commodities.

Demand analysis based upon the hypothesis of independent utilities, leads us to the conclusion “that in all cases a reduction in the price of one commodity only will either result in an expansion in the demand for all other commodities or in a contraction in the demands for all other commodities.” But this is quite contrary to the common cases found in the real world.

In the real world, it is found that as a result of the fall in price of a commodity, the demand for some commodities expands while the demand for others contracts. We thus see that Marshall’s analysis based upon ‘independent utilities’ does not take into account the complementary and substitution relations between goods. This is a great flaw in Marshall’s cardinal utility analysis.

On the other hand, this flaw is not present in Hicks-Allen indifference curve analysis which does not assume independent utilities and duly recognizes the relation of substitution and complementarity between goods. Hicks-Allen indifference curve technique by taking more than one commodity model and recognizing interdependence of utilities is in a better position to explain related goods. By breaking up price effect into substitution and income effects by employing the technique of compensating variation in income. Hicks succeeded in explaining complementary and substitute goods in terms of substitution effect alone.

Accordingly, it can define and explain substitutes and complements in a better way. According to Hicks, Y is a substitute for X if a fall in the price of X leads to a fall in the consumption of Y; Y is a complement of X if a fall in the price of X leads to a rise in the consumption of Y a compensating variation in income being made in each case so as to maintain indifference.

7. Analysing Consumer’s Demand with Less Severe and Fewer Assumptions:

It has been shown above that both the Hicks-Allen indifference curve theory and Marshall’s cardinal theory arrive the same condition for consumer’s equilibrium. Hicks-Allen condition for consumer’s equilibrium, that is, MRS must be equal to the price ratio amounts to the same thing as Marshall’s proportionality rule of consumer’s equilibrium.

But even here, ordinal approach of indifference curve analysis is an improvement upon the Marshall’s cardinal theory in so far as the former arrives at the same equilibrium condition with less severe and fewer assumptions.

Dubious assumptions such as:

(i) Utility is quantitatively measurable,

(ii) Marginal utility of money remains constant, and

(iii) Utilities of different goods are independent of each other, on which Marshall’s cardinal utility theory is based, are not made in indifference-curves’ ordinal utility theory.

Is Indifference Curve Analysis “Old Wine in a New Bottle”?

But superiority of indifference curve theory has been denied by some economists foremost among them are D. H. Robertson, F. H. Knight, W. E. Armstrong. Knight remarks, “indifference curve analysis of demand is not a step forward; it is in fact a step backward.” D. H. Robertson is of the view that the indifference curve technique is merely “the old wine in a new bottle.”

The indifference curve analysis, according to him, has simply substituted new concepts and equations in place of the old ones, while the essential approach of the two types of analyses is the same. Instead of the concept of ‘utility’, the indifference curve technique has introduced the term preference’ and scale of preferences. In place of cardinal number system of one, two, three, etc., which is supposed to measure the amount of utility derived by the consumer, the indifference curve have the ordinal number system of first, second, third etc. to indicate the order of consumer’s preferences.

The concept of marginal utility has been substituted by the concept of marginal rate of substitution. And against the Marshallian ‘proportionality rule’ as a condition for consumer’s equilibrium, indifference curve approach has advanced the condition of equality between the marginal rate of substitution and the price ratio.

Robertson’s view that the concept of marginal rate of substitution of indifference curve analysis represents the reintroduction of the concept of marginal utility in demand analysis requires further consideration. Robertson says. “In his earlier book Value and Capital Hicks’s treatment involved making an assumption of the convexity of the ‘indifference curves’ which appeared to some of us to involve reintroduction of marginal utility in disguise.”

It has thus been held that the use of marginal rate of substitution implies the presence of cardinal element in indifference curve technique. In going from one combination to another on an indifference curve, the consumer is assumed to be able to tell what constitutes his compensation in terms of a good for the loss of a marginal unit of another good. In other words, the consumer is able to tell his marginal rate of substitution of one good for another.

Now, the marginal rate of substitution has been described by Hicks and others as the ratio of the marginal utilities of two goods (MRSxy = MUx/MUy). But ratio cannot be measured unless the two marginal utilities in question are at least measurable in principle. One cannot talk of a ratio if one assumes the two marginal utilities (as the numerator and denominator) to be non-quantifiable entities. It has, therefore, been held that the concept of marginal rate of substitution and the idea of indifference based upon it essentially involves an admission that utility is quantifiable in principle.

Against this, Hicks contends that we need not assume measurability of marginal utilities in principle in order to know the marginal rate of substitution. He says, “All that we shall be able to measure is what the ordinal theory grants to be measurable— namely the ratio of the marginal utility of one commodity to the marginal utility of another.” This means that MRS can be obtained without actually measuring marginal utilities.

If a consumer, when asked, is prepared to accept 4 units of good Y for the loss of one marginal unit of X, MRS of X for Y is 4: 1. We can thus directly derive the ratio indicating MRS by offering him how much compensation in terms of good Y the consumer would accept for the loss of a marginal unit of X. Commenting on this point Tapas Majumdar writes: “The marginal rate of substitution in any case can be so defined as to make its meaning independent of the meaning of marginal utility. If marginal utilities are taken to be quantifiable, then their ratios certainly give the marginal rate of substitution; if the marginal utilities are not taken to be quantifiable the marginal rate of substitution can still be derived as a meaningful concept from the logic of the compensation principle.”

The contention that the concept of marginal rate of substitution is a mere reintroduction of the marginal utility (a cardinal concept) in disguise is therefore not valid. It follows from above that “if we do not assume that marginal utilities are measurable even in principle, we can still have the marginal rates of substitution which is another distinct advantage of the ordinal formulation.

It has been further contended by Robertson and Armstrong that it is not possible to arrive at the Hicksian principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution without making use of the ‘Marshallian scaffolding’ of the concept of marginal utility and the principle of diminishing marginal utility.

It is asked why MRS of X for Y diminishes as more and more of X is substituted for Y? The critics say that the marginal rate of substitution (MRSxy) diminishes and the indifference curve becomes convex to the origin, because as the consumer’s stock of X increases, the marginal utility of X falls and that of Y increases.

They thus hold that Hicks and Allen have not been able to derive the basic principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution independently of the law of diminishing marginal utility. They contend that by a stroke of terminological manipulation, the concept of marginal utility has been relegated to the background, but it is there all the same. They, therefore, assert that “the principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution is as much determinate or indeterminate as the poor law of diminishing marginal utility”.

However, even this criticism of indifference curve approach advanced by the defenders of the Marshallian cardinal utility analysis is not valid. As shown above, the derivation of marginal rate of substitution does not depend upon the actual measurement of marginal utilities. While the law of diminishing marginal utility is based upon the cardinal utility hypothesis (i.e., utility is quantifiable and actually measurable), the principle of marginal rate of substitution is based upon the ordinal utility hypothesis (i.e., utility is mere orderable).

As a consumer gets more and more units of good X his strength of desire for it (though we cannot measure it in itself) will decline and therefore he will be prepared to forego less and less of Y for the gain of a marginal unit of X. It is thus clear that the principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution is based upon purely ordinal hypothesis and is derived independently of the cardinal concept of marginal utility, though both laws reveal essentially the same phenomenon.

The derivation of the principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution by using ordinal utility hypothesis and quite independent of the concept of marginal utility is a great achievement of the indifference curve analysis. We therefore agree with Hicks who claims that “the replacement of the principle of diminishing marginal utility by the principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution is not a mere translation. It is a positive change in the theory of consumer’s demand”.

Further, in favour of ordinal indifference curve analysis, it is sometimes claimed that it is better since it can explain with fewer assumptions what cardinal utility theory explains with a larger number of assumptions. An eminent mathematical economist, N. Georgescu-Rogen, has argued that this point of view is very weak scientifically.

He remarks, “Could we refuse to take account of animals with more than two feet, on the ground that only two feet are needed for walking.” However, it may be pointed out that indifference curve analysis is held to be superior not merely because it applies fewer assumptions but because it is based upon more realistic and less severe assumptions. Apart from this, indifference curve theory is considered to be superior because,as explained above, it explains more than the cardinal theory.

It follows from what has been said above that indifference curve analysis of demand is an improvement upon the Marshallian utility analysis and the objections that the former too involves cardinal elements are groundless. It is of course true that the indifference curve analysis suffers from some drawbacks and has been criticized on various grounds, as explained below, but as far as the question of indifference curve technique versus Marshallian utility analysis is concerned, the former is decidedly better.

A Critique of Indifference Curve Analysis:

Unrealistic Assumptions:

Indifference curve analysis has come in for criticism on several grounds, especially it has been alleged that it is based on unrealistic assumptions. In the first place, it is argued that the indifference curve approach for avoiding the difficulty of measuring utility quantitatively is forced to make unrealistic assumption that the consumer possesses complete knowledge of all his scale of preferences or indifference map.

The indifference curve approach, so to say, falls from the frying pan into the fire. The indifference curve analysis envisages a consumer who carries in his head innumerable possible combinations of goods and relative preferences in respect of them. It is argued that carrying into his head all his scales of preferences is too formidable a task for a frail human being? Hicks himself admits this drawback.

When revising his demand theory based on indifference curves, he says that “one of the most awkward assumptions into which the older theory appeared to be impelled by its geometrical analogy was the notion that the consumer is capable of ordering all conceivable alternatives that might possibly be presented to him—all the positions which might be represented by points on his indifference map. This assumption is so unrealistic that it was bound to be a stumbling block. This is one of the reasons that Hicks has given up indifference curves in his Revision of Demand Theory.

Further, another unrealistic element present in indifference curve analysis is that such curves include even the most ridiculous combinations which may be far removed from his habitual combinations. For example, while it may be perfectly sensible to compare whether three pairs of shoes and six shirts would give a consumer as much satisfaction as two pairs of shoes and seven shirts, the consumer will be at a loss to know and compare the desirability of an absurd combination such as eight pairs of shoes and one shirt. The way the indifference curves are constructed, they include absurd combinations like the one just indicated.

A further shortcoming of the indifference curve technique is that it can analyse consumer’s behaviour effectively only in simple cases, especially those in which the choice is between the quantities of two goods only In order to demonstrate the case of three goods, three-dimensional diagrams are needed which are difficult to understand and handle. When more than three goods are involved geometry altogether fails and recourse has to be taken to the complicated mathematics which often tends to conceal the economic point of what is being done. Hicks also admit this shortcoming of indifference curve technique.

Another demerit of indifference curve analysis because of its geometrical nature is that it involves the assumption of continuity “a property which the geometrical field does have, but which the economic world, in general, does not”. The real economic world exhibits discontinuity and it is quite unrealistic and analytically bad if we do not recognize it. That is why Hicks too has abandoned the assumption of continuity in his A Revision of Demand Theory.

Armstrong’s Critique of the Notion of Indifference and the Transitivity Relations:

Armstrong has criticized the relation of transitivity involved in indifference curve technique. He is of the view that in most cases, the consumer’s indifference is due to his imperfect ability to perceive difference between alternative combinations of goods.

In other words, the consumer indicates his indifference between the combinations which differ very slightly from each other not because they give him equal satisfaction but because the difference between the combinations is so small that he is unable to perceive the difference between them. If this concept of indifference is admitted, then the relation of indifference becomes non-transitive. Now, with non-transitivity of indifference relation; the whole system of indifference curves and the demand analysis based upon it breaks down.

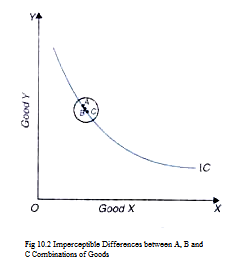

The viewpoint of Armstrong is illustrated in Fig. 10.2 Consider combinations A, B and C which lie continuously on indifference curve IC. According to Hicks-Allen indifference curve analysis, consumer will be indifferent between A and B, and between B and C. Further, on the assumption of transitivity, he will be indifferent between and C.

According to Armstrong, the consumer is indifferent, say, between. A and B not because the total utility of combination A is equal to the total utility of combination B but because the difference between the total utilities is so small as to be imperceptible to the consumer.

However, if we compare A with C, the difference between the total utilities becomes large enough to become perceptible. Thus, the consumer will not remain indifferent between and C; he will either prefer A to C, or C to A.

So on Armstrong’s interpretation, the relation of indifference between A and B, B and C which was due to the fact that the difference in utilities was imperceptible will not hold between A and C since the difference in utilities between A and C becomes perceptible. If Prof. Armstrong’s interpretation is admitted; the indifference relation becomes non-transitive and the theory of consumer’s demand based on the indifference system falls to the ground.

Another way in which Armstrong’s argument has been refuted is the adoption of ‘statistical definition’ of indifference, as suggested by Charles Kennedy. According to the statistical definition, the consumer is said to be indifferent between the two combinations when he is offered to choose between those two combinations several times and he chooses each combination 50 per cent of the time. However, there are some serious difficulties in adopting the statistical definition. But if the statistical definition of indifference is adopted, then also the indifference relation between A and B, B and C, C and D etc., becomes transitive and in that case, therefore, Armstrong’s criticism does not hold good.

Cardinal Utility is Implicit in Indifference Curve Analysis: Robertson’s View:

Further, another criticism of indifference curve analysis is made by D.H. Robertson who asserts that indifference curve analysis implicitly involves the cardinal measurement of utility. He points out that Pareto and his immediate followers who propounded ordinal indifference curve analysis continued to use the law of diminishing marginal utility of individual goods and certain other allied propositions with regard to complements and substitutes.

In order to do so, Robertson asserts that “you have got to assume, not only that the consumer is capable of regarding one situation as preferable to another situation, but that he is capable of regarding one change in situation as preferable to another change in situation. Now, while the first assumption does not, it appears that the second assumption really does compel you to regard utility as being not merely orderable but a measurable entity.

He explains this point with the help of Fig. 10.3. According to him, if the consumer can compare one change in situation with another change in situation, he can then say that he rates the change AB more highly than the change BC. If such is the case, it is then always possible to find the point D so that he rates the change AD just as highly as the change DC and “that seems”, says Robertson, “to be equivalent to saying that the interval AC is twice the interval AD, we are back in the world of cardinal measurement. How far Robenson’s contention is valid is however a matter of opinion.

Indifference Curve Analysis is a midway house:

Further, indifference curve analysis has been criticised for its limited empirical nature. Indifference curve analysis is neither based upon purely imaginary and subjective utility functions, nor is based upon purely empirically derived indifference functions. It is because of this fact that Schumpeter has dubbed indifference curve analysis as ‘a midway house’. It would have been quite valid if indifference curve analysis was based upon experimentally obtained quantitative data in regard to the observed market behaviour of the consumer. But, in Hicks-Allen theory, indifference curves are based upon hypothetical experimentation.

The indifference curve theory of demand is, therefore, based upon imaginarily drawn indifference curves. Commenting on Hicks-Allen theory of demand, Schumpeter remarks, “If they use nothing that is not observable in principle they do use “potential” observations which so far nobody has been able to make infact from a practical standpoint we are not much better off when drawing purely imaginary indifference curves than we are when we speak of purely imaginary utility functions.

It may, however, be pointed out that attempts have recently been made by some economists and psychologists to derive or measure indifference curves experimentally. But a limited success has been achieved in this regard. This is because such experiments have been made under controlled conditions which render these experiments quite unfit for drawing conclusions regarding real consumer’s behaviour in ‘free circumstances’. So, for all intents and purposes, indifference curves still remain imaginary.

Failure to analyse Consumer’s Bahaviour under Uncertainty:

An important criticism against Hicks- Allen ordinal theory of demand is that it cannot formalise consumer’s behaviour when uncertainty or risk is present. In other words, consumer’s behaviour cannot be explained by ordinal theory when he has to choose among alternatives involving risk or ‘uncertainty of expectation’. Von Neumann and Morgenstern and also Armstrong have asserted that while cardinal utility theory can, the ordinal utility theory cannot formalise consumer’s behaviour when we introduce “uncertainty of expectations with regard to the consequences of choice.”

Let us consider an individual who is faced with three alternatives A, B and C. Suppose that he prefers A to B, and C to A. Suppose also that while the chance of his getting A is certain, the chance of his getting B or C is fifty-fifty. Now, the question is which alternative will the consumer choose. It is obvious that the choice he will make depends on how much he prefers A to Band C to A.

If, for example, A is very much preferred to B, while C is only just preferred to A, then he will surely choose A (certain) rather than fifty-fifty chance of C or B. But unless the consumer can say how large his preferences for A over B, and for Cover A are, we cannot know which alternative he is likely to choose.

It is obvious that a consumer who is confronted with the choice among such alternatives, will often compare the relative degree of his preference of A over B and the relative degree of his preference for C over A with the respective chances of getting B or C. Now, a little reflection will show that ordinal utility system cannot be applied to such a situation, for in such a situation, the choice is determined if the consumer knows the differences in the amounts of utility or satisfaction he gets from various alternatives.

According to ordinal utility theory, individual cannot tell how much more utility he derives from A than B, or, in other words, he cannot tell whether the extent to which he prefers A to B is greater than the extent to which he prefers C to A.

We thus find that Hicks-Allen ordinal utility system cannot formalise consumer’s behavior when there exists uncertainty of expectation with regard to the consequences of choice. On the other hand, cardinal utility theory can formalise consumer’s behavior in the presence of uncertainty of expectations since it involves quantitative estimates of utilities or preference intensities.

Commenting on indifference preference hypothesis, Neumann and Morgenstern remark. “If the preferences are not all comparable, then the indifference curves do not exist. If the individual preferences are all comparable, then we can even obtain a (uniquely defined) numerical utility which renders the indifference curves superfluous.”

Drawback of Weak-ordering Hypothesis and Introspective Approach:

An important point be noted regarding indifference curves is that it is based upon the weak ordering hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the consumer can be indifferent between certain combinations. Though the possibility of relation of indifference is not denied, it is pointed out that indifference curve analysis has exaggerated the role of indifference in demand theory.

The innumerable position of indifference, assumed by Hicks-Allen theory, is quite unrealistic. Hicks himself later realised this shortcoming of indifference curve analysis, as is clear from the following remarks in his “Revision of Demand Theory, “The older theory may have exaggerated the omnipresence of indifference; but to deny its possibility is purely to run to the other extreme.”

Further, Paul A. Samuelson has criticized the indifference curves approach as being predominantly introspective. Samuelson himself has developed a behaviourist method of deriving the theory of demand. He seeks to enunciate demand theorem from observed consumer’s behaviour. His theory is based upon the strong-ordering hypothesis, namely, ‘choice reveals preference’. Samuelson thinks that his theory sloughs off the last vestiges of the psychological analysis in the explanation of consumer’s demand.

Limitations of Marimizing Behaviour:

In the last place, indifference curve analysis has been criticized for its assumption that the consumer ‘maximizes his satisfaction’. Since Marshall also assumed this maximizing behavior on the part of the consumer, this criticism is equally valid in the case of Marshallian utility analysis also. It is asserted that it is quite unrealistic to assume that the consumer will maximize his satisfaction or utility in his purchases of goods.

This means that the consumer will try to reach the highest possible indifference curve. He will get maximum satisfaction when he is equating the marginal rate of substitution between the two goods with their price ratio. It is pointed out that the consumer of the real world is guided by custom and habit in his daily purchases whether or not they provide him maximum satisfaction. The real consumers are slaves of custom and habit.

The housewife, it is said, purchases the same amount of milk, even if its price has gone up a bit, though on the basis of maximizing postulate this change in price should have made her readjust her purchases of milk. If a housewife is asked about her marginal rate of substitution of milk for bread, she will show complete ignorance about this. Further, if you ask her whether she equates the marginal rate of substitution with the price ratio while making purchases; she is sure to tell you that she never indulges in achieving such mathematical equality.

But this criticism is not very much valid. A theory will be true even if the individuals unconsciously behave in the way assumed by the theory. Robert Dorfman rightly remarks: “It is only the result that counts for a descriptive theory, not the conscious intent. The strands of a bridge cable do not know what they are supposed to do in the form of a quaternary, they just do it”. Thus the question of the indifference curve theory to be valid or not hinges upon whether the consumers behave in the way assumed by the theory.

The answer is yes; the consumers do behave in the way asserted by the theory. Taking the above example, when the price of milk goes up and high price persists, the housewives will notice that their milk bills are getting out of line and will take steps to save on milk here and there in their daily consumption. This will ultimately reduce the quantity demanded of milk.

The reactions to changes in the prices of other goods are similar. If the price of a durable consumer good rises, the consumers may continue to use the present stock of it for a longer time than they had planned to replace it. If the close substitutes of the good in question exist, then they may give it up and replace it by any relatively cheaper substitutes. In these and various other ways the consumers will prevent prices of goods from getting far out of line from their marginal rates of substitution.

It is, therefore, clear that consumers do actually behave in accordance with the maximizing postulate though unconsciously, and roughly equate marginal rate of substitution of money for a good with the price of the good, though they may not be knowing what the marginal rate of substitution is. However, it may be noted that while examining the question as to whether or not consumer’s behavior is in accordance with the maximization assumption, the theory should not be taken too literally.

The ordinary consumer cannot be expected to equate precisely the marginal rate of substitution of money for a good with the price of the good. In the first place, many goods in the real world are indivisible (i.e., available only in large units). This indivisibility of goods renders precise adjustment of the quantities of goods impossible and thus prevents the equality of the marginal rate of substitution of money for a good with its price.

The two main examples of indivisible goods are cars and television sets. In such cases, if we want to be precise we must make a more elaborate statement about consumer’s equilibrium, namely, a consumer will purchase such a number of units of good that an addition of one more unit to it would cause the marginal rate of substitution of money for the good lower than its price. “But this elaboration” as rightly asserted by Dorfman, “is only a detail and not a change in principle.

Secondly, another fact that prevents the equality of marginal rate of substitution with the price is that no consumer buys all goods. For instance, bachelors do not buy diapers; non- drivers do not buy gasoline. The marginal rate of substitution of money for diapers for bachelors is equal to zero and thus is not equal to price.

In such cases also, if we want to be precise we have to make another modification in our theory of consumer’s equilibrium. “If the marginal rate of substitution of money for a commodity is less than its price when no units are purchased, then none will be purchased.” But this modification also is simply a refinement and not a change in basic principle.