Capital embodied in human beings in the form of education and health which make them more productive is called human capital.

Read this article to learn about Introduction to Human Capital, Human Capital and Economic Development and Cost of Human Capital.

Human Capital: Introduction, Economic Development, Cost of Human Capital

1. Introduction to Human Capital:

Capital embodied in human beings in the form of education and health which make them more productive is called human capital.

Physical capital human resources or human capital plays a significant role in determining economic development. More education makes the human beings more productive through enhancing their skills, abilities, knowledge and better health enables them not only to participate in the production process but increase their capabilities to produce more.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus education and health can add to the value of production in the economy and also to the incomes of the persons who have been educated and made healthy.

The human capital is embodied in human beings. Human capital comprises the education, knowledge, the skills, better health and the capacities of all people in the society to undertake production.

On the other hand, the physical capital consists of produced means of production such as machines that are used in producing other goods. Economic development calls for both forms of capital accumulation. And both forms of capital call for investment.

Investment in human capital has therefore been called ‘investment in man’. Education plays a crucial role in the ability of a country to absorb modern technology and to generate the capacity for self-sustained growth and development. Health is also essential for increase in productivity of labour and, therefore, not only raises the private incomes but also contributes to the growth of GDP.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, Todaro and Smith write, “Both health and education can also be seen as vital components of growth and development as inputs to the aggregate production function. Their role as both inputs and output gives health and education their central importance in economic development.”

Till recently economists have been considering physical capital as the most important factor determining economic growth and have been recommending that rate of physical capital formation in developing countries must be increased to accelerate the process of economic growth and raise the living standards of the people. But in the last three decades economic research has revealed the importance of education as a crucial factor in economic development. Education refers to the development of human skills and knowledge of the people or labour force.

It is not only the quantitative expansion of educational opportunities but also the qualitative improvement of the type of education which is imparted to the labour force that holds the key to economic development.

Because of its significant contribution to economic development, education has been called as human capital and expenditure on education of the people as investment in man or human capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Speaking of the importance of education or human capital, Prof. Harbison wrote “Human resources constitute the ultimate basis of production; human beings are the active agents who accumulate capital, exploit natural resources, build social, economic and political organisations, and carry forward national development. Clearly, a country which is unable to develop the skills and knowledge of its people and to utilise them effectively in the national economy will be unable to develop anything else.”

# 2. Human Capital and Economic Development:

Gross domestic product of a country depends on not only the amount of labour (i.e. work-hours) used for producing goods and services but also on its productivity. One of the important factors that determine productivity of worker is human capital, that is, education.

As seen above, in the modern economics the concept of capital is not confined to physical capital such as machines, tractors, capital equipment, etc. that raises productivity of labour but also includes what is called human capital.

By human capital we mean the skills and knowledge that workers acquire through education and training. This human capital, that is, knowledge and skills, are accumulated by human beings through education during the time they spend in primary and secondary schools and up to graduation and post-graduation in colleges or universities.

Besides, specialised professional education such as engineering, computer training, management education and others raises greatly the productivity of workers. Therefore, accumulation of human capital is generally called investment in people.

Just as a firm considers whether to invest in physical capital, individuals decide whether to invest in their own human capital. When a firm purchases machinery or other capital equipment to produce more output and increases its future profits, individuals invest in education or acquiring skills to raise their productivity and their future earnings. Investment in education or acquiring new skills is called investment in human capital.

While usual models of labour supply assume that wage rate of individuals is fixed, however through investment in human capital the individuals can raise their wages or earnings as investment in human capital raises their productivity and it has been found that in the United States rate of return on investment in secondary education is 10 to 13 per cent higher.

According to Prof. Amartya Sen, the improvement in the availability and quality of education results in higher level of functionings and capability of labour. He has shown in his works that for a country a low level of education lowers the growth of GDP due to shortages of labour with appropriate skills.

Besides, the empirical evidence available suggests that countries which have invested more in education as measured by average years of schooling tend to experience, other things remaining constant, higher rate of growth. Furthermore, higher technical education helps to discover new inventions and innovations and thereby promote technological progress.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Human capital, though less tangible than physical capital, is similar to it in many ways. First, like physical capital, accumulation of human capital increases the ability of a country to produce more goods and services. Secondly, like physical capital, human capital is a produced factor of production.

Producing human capital requires investment in inputs such as student time, teachers, books and libraries, college buildings. Thirdly, like the physical capital, the accumulation of human capital increases the productivity of workers and therefore causes their wages to rise. Fourthly, like the accumulation of physical capital, the accumulation of human capital requires the sacrifice of some present consumption so as to have more consumption in future.

# 3. Cost of Human Capital or of Acquiring Skills:

Human capital is built through acquiring more education or skills by spending more time in school, college or university.

Thus, in spending more time in acquiring more education, one not only delays one’s entry into labour force but also sacrifices income or wages which he could have earned by working during the time he spends for acquiring education. This is the opportunity cost of acquiring more education, skills and grades (i.e., accumulating more human capital).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But they spend time in acquiring more human capital with the expectation that they would be able to earn higher income or wages in the future as more education and higher skills raise the productivity of the workers and therefore their wages.

Thus, the students, like the people who save, face a trade-off between less consumption today for more consumption in the future.

Thus, “spending more on education today (reducing consumption) raises future income but each additional investment in education provides a smaller and smaller return”. It follows from above that, like physical capital, expenditure on education also represents investment in capital which raises productivity in the future.

Besides, investment in education is tied to specific human being and therefore it is called human capital. Thus, according to Mankiw, “Like all forms, capital education represents an expenditure of resources at one point in time to raise productivity in the future.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But unlike an investment in other forms of capital, investment in education is tied to a specific person and this linkage is what makes it human capital.” It is important to note that workers endowed with higher education (i.e., more human capital) earn more income or wages than those having less education.

The differences in wages between those with more education and those with less education are quite large and have been increasing. For example “College graduates in the United States earn about twice as much as those workers who end their education with a high school diploma “.

It may be noted that this difference in earnings between workers with more human capital and those with less human capital on an average tends to be even larger in developing countries where educated workers are in scarce supply.

That investment in education or human capital has a cost can be easily illustrated. Economists are generally concerned with the opportunity cost of time spent in acquiring education or human capital. If you are attending a class acquiring education you cannot be working simultaneously at a job yielding you some income.

Therefore, by attending computer classes you forgo some wages or earnings and hence some consumption which represents the cost of acquiring human capital.

How decision regarding more investment in education (human capital) involves trade-off between consumption in the period of youth and consumption in later working years is depicted in Fig. 9.1 through production possibility curve PP’. On the horizontal axis consumption in youth is measured, while consumption in later working years (i.e., the period of adulthood) is measured along the vertical axis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this situation a individual’s consumption is C0 in the youth and C1 in the adulthood period. Thus the situation at point A represents what is called the endowment point. Now suppose individual has the opportunities to attend classes of computer programming which is in fact a decision to make investment in human capital. By attending the computer programming classes the individual would have to forgo some present consumption as he would not be working to earn income during that period.

However, by acquiring the knowledge of computer programming he would be enhancing his productivity and earning capacity in the adulthood period. In fact, more time he spends in attending acquisition of computer education, the higher will be his earnings in the adulthood period.

However, this process of spending more time in getting education of computer programming is subject to diminishing marginal returns. Each extra hour of computer class raises his earning ability by successively smaller marginal amount. With these assumptions, the opportunities of the individual are reflected in production possibility curve PP’ in Fig. 9.1.

It will be seen that this production possibility curve PP’ is concave to the origin and its curvature implies that each rupee reduction in consumption in the present period (that is, in youth) increases the future earnings in terms of consumption by successively smaller increments.

The production possibility curve PP’ drawn in Fig. 9.1 is therefore often referred to as human capital production function. It shows how consumption in the present period is forgone and transformed into human capital investment and higher earnings in the adult period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To determine how much time an individual will spend on obtaining computer education or skill formation, that is, human capital investment depends on his preference between present consumption and future consumption. In fact, human capital investment decision (i.e., investment in education or skill formation), requires trade-off between lower consumption level in the present in return for higher earnings in the future.

To determine what level of human capital investment the individual will choose, we need to introduce indifference curves regarding individual’s preference between present consumption and future consumption. For this we superimpose indifference curves upon his production possibility curve PP’ given in Fig. 9.1.

It will be seen from Fig. 9.1 that individual will choose point E at which he will be consuming C’0 in the present period of youth and C’1 in the adulthood period. This means that his sacrifice of consumption in the period of youth equal to C’0– C0 has led to a much larger increase in his consumption C’1-C1 in the adulthood as a result of higher earnings made possible by investment in human capital.

Return on Investment in Education:

The studies conducted by the World Bank show that economic returns on investment in education appears to be higher than in alternative kinds of investment, especially in physical capital.

Further it has been found that rate of return to education of all the three levels in developing countries is higher than in developed countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

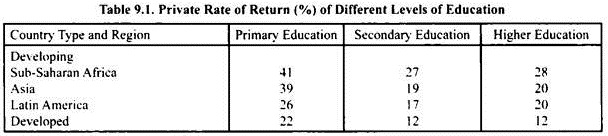

An important study based on available statistical data of both developing and developed countries was made by George Psacharopoulos found that in the early 1990s private returns on primary, secondary and higher education were higher in developing countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America than the developed countries (Table 9.1).

For instance, private return to primary education was 41% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 39% in Asia, 26% in Latin America as compared to 22% in developed OECD countries.

Another fact worthwhile to note is that private return to education tends to fall as level of development (measured by the level of per capita income) increases.

Besides, there are social returns to investment in education which take into account the externalities which do not enter into the calculations of private individuals in their assessment of private return on education.

Education and Sources of Economic Growth:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The supply of human capital plays a crucial role in promoting economic growth. In an important study, Edward F. Denison has measured the relative importance of various sources of economic growth in the United States for the 50 years period, 1929-69.

Rate of economic growth in the US economy was on an average 3.3 percent during the period 1929-69 of the study. It will be seen from Table 9.2 that the most important source of economic growth (31.1 to 34 per cent) was advances in knowledge (which includes improvement in technological knowledge) that takes place as a result of increase in education and in research and development activity. The next important source of economic growth was increase in the quantity of labour force (i.e., more work done) as measured by increase in hours worked by labour which contributed about 28.7 per cent during the period of study.

Contrary to expectations of economists, accumulation of physical capital contributed only 15.8 per cent during the entire period (1929-69) and 21.6 per cent during 1948-69 to the growth in GDP in the United States. For the entire period of study (1929-69) increase in education (i.e., number of years spent in schools, colleges and universities) contributed almost the same as accumulation of physical capital (14.1 per cent as against 15.8 per cent of physical capital. However, if we club the contribution of increased education and advances in knowledge, their contribution is as high as about 45 per cent to growth.

Other sources include the efficient use of available resources, economies of scale, a shift of labour force from low-productivity agricultural sector to higher productivity industrial sector which contributed about 10 per cent to growth in GDP. It may however be noted that Denison could not measure directly the contribution of advances in knowledge. He measured the contributions of other four sources of growth, namely, more labour work, accumulation of physical capital, increased education, and others, and assumed that all economic growth that could not be explained by other sources was the contribution of advances in knowledge.

As it pays to the individual to invest in human capital (education or skill formation), similarly, the community as a whole can raise its consumption or living standards by investing in human capital.

4. Measuring Contribution of Education to Economic Growth:

Several empirical studies made in developed countries, especially the U.S.A., regarding the sources of growth or, in other words, contributions made by various factors such as physical capital, man-hours, (i.e., physical labour), education etc. have shown that education or the development of human capital is a significant source of economic growth.

It may be pointed out that economists generally hold that while some investments in education are ‘economic’ in the sense that they promote growth directly, other expenditures on education and development of the human resources are basically of the form of ‘social investment’ which, therefore, should be determined residually. It is not possible to separate out the consumption and investment parts of the expenditure on education so that it is very difficult to estimate the rate of financial return on education in the same manner as in the case of a factory or a dam. At best, one can only recognize the probable importance of the expenditure on education in the process of economic growth.

The estimation of return on investments in education or human capital is beset with many difficulties. The fact is that human resource development encompasses a wide field. It cannot be solely examined in economic terms. For instance, it is not very realistic to estimate the return on education purely in terms of the increases in individual incomes or the income of the economy taken as a whole. Also, the increases in productivity do not by themselves constitute the effectiveness of human capital. Notwithstanding these considerations, economists have attempted to measure the contribution of education to economic growth solely on the basis of economic criteria.

In broad outline, the basis on which return and therefore, role of investment in human resources, particularly education, has been sought to be incorporated in the mainstream of economic analysis.

The following are the main approaches that have been developed to gauge the productivity of investment in education:

1. The Residual Approach or Production Function Approach:

There have been some attempts to estimate the proportion of the measured increase in gross national product attributable to education. This is sought to be done by first determining the increase in gross national product on account of the measurable inputs of labour and capital. Then this figure is subtracted from the figure of GNP, to get a ‘residue’ which represents the increase in GDP due to the improvements in the quality of labour as a consequence of education.

Professor Solow who was one of the first economists to measure the contribution of human capital to economic growth, estimated that for United States between 1909 and 1949, 57.5per cent of the growth in output per man-hour could be attributed to the residual factor which represents the effect of the technological change and of the improvement in the quality of labour mainly as a consequence of education. He estimated this residual factor determining the increase in the total output on account of the measurable inputs of capital and labour (man hours). He then subtracted this figure from the total output to get the contribution of residual factor which represented the effect of education and technological change, the physically immeasurable factors.

As explained above, Denison, another American economist, made further refinement in estimating the contribution to economic growth of various factors. Denison tried to separate and measure the contributions of various elements of ‘residual factor’. According to the estimates of Denison, over the period 1929-82 in the USA during which total national output grew at the rate of 2.9 per cent per annum, increase in labour input accounted for 32 per cent, the remaining 68 per cent was due to the increase in productivity per worker. He then measured the contributions of education of per worker, capital formation, technological change and economies of scale.

Denison found that 28 per cent of contribution to growth in output due to growth in labour productivity was due to technological change, 19 per cent to capital formation and 14 per cent due to education per worker and 9 per cent points due to economies of scale. It is thus clear that education and technological progress together made 42 per cent (14 + 28) contribution to growth in national product.

Limitations:

However, the above estimates are not fully reliable. The basic reason for this is that the methods used in calculating the contribution of education, are not free from flaws. Moreover, the data which have been used in the calculations applies only to formal education. It completely ignores on-the-job training. Also, only private return on education is measured. But education makes a considerable social contribution also in the form of increased mobility, adaptability and the growth of applied technology. In this sense, these calculations make underestimation of the contribution of education.

There being interrelation between capital formation, technology and growth of knowledge, the component in the residual ascribed to increased knowledge may, in fact, include some capital assets. But, in these methods no distinction has been made between formal and informal education. Again, the differences in the quality or content of education have been ignored.

Notwithstanding these limitations, these estimates highlight the significance of the improvements in the quality of human resources through education, in the process of economic growth.

2. Rate of Return Approach– Further Elaboration:

The contribution of education to economic growth has also been measured through the rate of return approach. In this approach rate of return is calculated from expenditure made by individuals on education and the measurement of the flow of an individual’s future earnings expected to result from education. The present value of these is then calculated by using appropriate discount rate. For calculating the present value of future earnings with education the appropriate present value formula is used. This method has been used by Gary S. Backer who measured income differential arising from the cost or expenditure incurred on acquiring a college education in the United States. His estimates show that the rates of return on education in the U.S.A. for urban white population were 12.5 per cent in 1940 and 10 per cent in 1950.’

Another study on similar lines was made by E.F. Reneshaw. He used Schultz’s earlier estimates, for USA of total earnings forgone and the cost of education in high schools, colleges and university. Doing this, he found that the average return on education ranged between 5 and 10 per cent for the period 1900 to 1950.

It is worth noting that estimates of rate of return on investment in education are based upon private rates of returns to individuals receiving education. However, by assuming that differences in earnings in a market economy reflect differences in productivity, the rate of return on investment in education is taken to be the effect of education on the output of the country.

Limitations:

However, these estimates of the return on education are valid only to the extent to which the underlying assumptions are valid. The expenditure on education has two components- the future earnings and the future consumption. While the educational investment results in increase in the future earnings, it also entails the consumption element in the sense of the direct satisfaction derived from education so obtained.

The latter, i.e., the consumption component of investment in education wherein resides the source of future utilities, nowhere enters into the measured national income. To the extent these estimates ignore the future utilities and other external economies of acquiring knowledge; they underestimate the returns on education.

Moreover, the earning capacity of individuals with varying educational levels is not entirely the function of formal education. Other factors such as on-the-job training, experience, family income, social status and natural abilities also influence the earning capacity. But the estimates of return on education take no account of these other factors.

Furthermore, these estimates concentrate only on the measurement of the private rates of return on educational investment. At best, they take into account merely the indirect effects of education on the output of the country on the assumption that the earnings differentials in a market economy reflect the differentials in productivity. But the various groups such as engineers, doctors, teachers and manual workers through collective efforts or trade unionism may distort the relative earnings in the economy. What is more, it is difficult to even estimate the private returns on education where the costs of running an educational institution are negligible. For instance, in India there are a large number of single teacher schools where no fee is charged from the pupils.

Again, as has been argued by Eckaus, the cost (or price) of educated labour which is used in evaluating the rate of return ought to reflect the relative scarcities of the factors involved. However, when the primary burden of educational investment is borne by the government, the prices of educated labour fail to reflect the scarcities of factor inputs that are so used.

Also, these estimates of rate of return on education undervalue the importance of education as a stepping stone to further education. The fact is that one level of education leads to another. As such, a comparison of individuals with primary education with those who lack it would simply underestimate the significance of primary education as the basic prerequisite to acquire further education. Further, these estimates of return on education provide no information as to the quantity and quality of education most conducive to economic development.

3. Schultz Approach – Comparing Expenditure on Education with Income Earned:

Another approach to measure the contribution of education is based upon the analysis of the relationship between expenditure on education and income. Using this approach Schultz studied the relationship between expenditure on education and consumer’s income and also the relationship between expenditure on education and physical capital formation for the United States during the period 1900 to 1956.

He found that when measured in constant dollars, “the resources allocated to education rose about three and a half times (a) relative to consumer income in dollars, (b) relative to the gross formation of physical capital in dollars”. This implies that the “income elasticity” of the demand for education was about 3.5 times over the period or in other words, education considered as an investment could be regarded as 3.5 times more attractive than investment in physical capital. It may however be noted that these estimates of Schultz only indirectly reflect the contribution of education to economic growth.

In the above analysis it is explained that education is regarded as investment and like investment in physical capital, it raises productivity of the labour and thus contributes to growth of national income. The increased earnings or higher wages made by more educated workers have been considered as benefits not only to the private individuals, but also to the society as a whole. This is because higher earnings presumably reflect higher productivity, increased output in real as well as monetary terms.

Consumption Benefits of Education:

We have explained above the investment benefits of education and therefore its effects on productivity and national output. But investment benefits are the only benefits flowing from education. Education also yields consumption benefits for the individual as he may “enjoy” more education; derive increased satisfaction from his present and future personal life. If the welfare of society depends on the welfare of its individual members, then the society as a whole also gains in welfare as a result of the increased consumption benefits of individuals from more education. Economic theory also helps us in quantifying the consumption benefits derived from education. In economic theory, to measure the marginal value of a product or service to a consumer we consider how much he has paid for it.

An individual would not have purchased a product or service if it were not worth its price to him. Besides, an individual would have bought more units of a product if he thought that the marginal utility he was getting was more than the price he was paying. Thus relative prices of various products reflect the marginal values of different products and the amount consumed of various products multiplied by their prices would, therefore, indicate the consumption benefits derived by the individuals.

It may, however, be pointed out that the prices in a free economy are influenced by a given income distribution and the presence of monopolies and imperfections in the market structure and therefore they do not reflect the true marginal social values of different goods. However, an objective measure of consumption benefits of education is difficult and has yet to be found out. It may also be noted that, according to the new view, economic development is not merely concerned with the growth of output but also with the increase in consumption and well-being of the society.

Thus Prof. Amartya Sen writes, “Education can add to the value of production in economy and also to the income of the person who has been educated. But even with the same level of income, a person may benefit from education in reading, communicating, arguing, in being able to choose in a more informed way, in being taken more seriously by others and so on”. Therefore, consumption benefits of education may also be regarded as developmental benefits.

External Benefits of Education:

We have explained above the investment benefits and consumption benefits flowing from more education both for the individual and the society. The analysis of benefits has been based on the assumption that private interests of individuals are consistent with the social good. However, private and social benefits do not always coincide; for instance, social benefits may exceed private benefits.

This is the case with the education of an individual which not only benefits individual privately but also others. First, education makes people better neighbours and citizens and makes social and political life more healthy and meaningful. Secondly, the, most important external benefit of more education is its effect on technological change in the economy. More education, especially higher education, stimulates research and thereby raises productivity which undoubtedly benefits the society.

The individual inventor may not receive earnings equal to his contribution to the research. Denison’s study of contribution of education to growth, whose main findings have been explained, clearly shows the external benefits of education. After estimating the contribution of labour (including educated labour) and physical capital to economic growth he obtained an average residual of about 32 percentages to annual growth of 2.9 per cent in the U.S. during the period 1929-60. Denison attributed this to the increase in knowledge which is the direct result of research and indirectly of higher education.

This is in addition to 14 per cent contribution to the annual growth made directly by increase in education. Therefore, Harris and James concludes – “If the entire residual indeed stemmed ultimately from education, as some human capital enthusiasts have implied, this would mean that education, directly or indirectly, contributed over 40 per cent of total output growth and 80 per cent of increased productivity from 1929 to 1957.” If Denison’s residual is regarded as mainly due to research stimulated by additional education, then this is indeed a major external benefit of education.