Average-cost pricing practices have been widely supported by empirical studies, it has been found that this pricing practice is adopted by a large number of small and large firms in most industries.

This, however, does not establish that average-cost pricing is a theory different than other theories of the firm.

Average-cost pricing practices are compatible with almost all hypotheses pertaining to explain the behaviour of the firm.

For example average-costing rules of pricing are compatible with Baumol’s sales maximisation hypothesis, Cyert and March’s satisficing behavioural model, with short-run marginalistic profit-maximising behaviour (e.g. in the monopolistic competition models of Chamberlin and Joan Robinson the final tangency equilibrium may be arrived at either by equating MC to MR, or by setting P = AC), and with long-run profit maximisation of the sort earlier described. The question then arises whether average-cost pricing is a different theory of the firm, or whether it is a pricing practice (a pricing routine), adopted by firms for various reasons, irrespective of their goals.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It should be clear that the ‘mark-up’ margin would be different, depending on the goals of the firm, and hence the price level would be different. Thus, unless we know what the goals of the firm are, we cannot say just by looking at its pricing rules of thumb whether it is a sales maximiser, a satisficer, or a firm aiming at the long-run profit maximisation, because all these motivations may be attained by applying an average-cost routine in price setting. However, the empirical evidence regarding the goals of the firm is far from conclusive.

What is established from various studies is that:

(a) The average-cost pricing practice is widely adopted by firms in the modern industrial world.

(b) The prices are not adjusted as soon as a change in demand or costs takes place, as the narrow marginalistic behaviour (of equating MC to MR) would imply. Thus short-run profit maximisation by applying the marginalistic rule MC — MR in each period within the time-horizon of the firm has been refuted by empirical studies,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) The shifting of corporate taxes to the buyers through price increases is a well-established fact, but this is compatible, with many motivations-goals (e.g. Baumol’s theory yields the same qualitative predictions as long-run profit maximisation pursued by equating price to AC),

(d) In some studies it has been reported that prices have been ‘sticky’ over long periods over which cost conditions and demand conditions have been changing.

This stickiness of prices is incompatible with short-run marginalistic behaviour, but is compatible not only with long-run profit maximisation (based on the average-cost principle) but also with collusive agreements, price-leadership models, etc., and can be explained by a kinked-demand curve which can plausibly be accepted not as a price theory but as describing the beliefs (subjective assessment) of businessmen about the probable behaviour of their rivals.

(e) It is generally found by empirical studies that firms have a multiplicity of goals, and not the single goal of profit maximisation. This evidence may be interpreted as refuting average-cost pricing as a theory, since this postulates a single goal, that of long-run profit maximisation. The proponents of average-cost pricing theory would, however, resort to ‘survival arguments’ in support of the long-run profit- maximisation goal. For example, some argue that other goals can be attained more easily if firms maximise profits; others, that there is a mechanism of economic selection’ analogous to the biological Darwinian law of ‘natural selection’ which postulates the ‘survival of the fittest’. These arguments cannot be resolved on a priori grounds.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

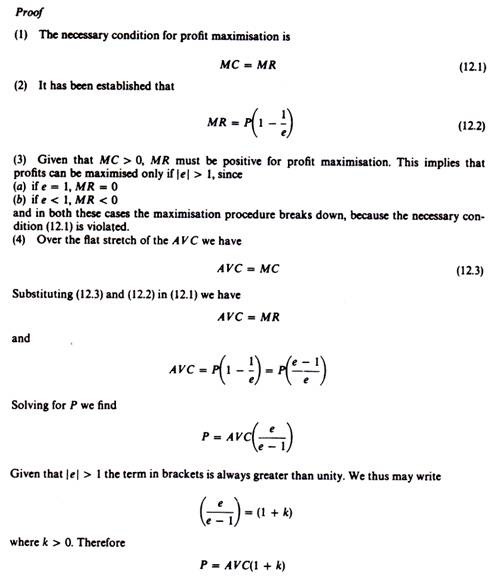

However, even if one accepted that long-run profit maximisation is the single goal of the firm, average-cost pricing would not be a new theory of the firm, since it can be proved that the same long-run equilibrium solution would be reached if one applied marginal analysis in the long run. We will prove that setting the price on the basis of the average-cost principle involves implicitly the (subjective) estimation of the elasticity of demand in the long-run equilibrium position. In other words, when the firms apply the mark-up rule

P = AVC + GPM

with the aim of attaining maximum profits in the long run, they implicitly ‘guess’ at the value of the demand elasticity, provided that the AVC is constant over the relevant range of output (and the empirical evidence from cost studies shows that the A VC is constant over the range of output within which firms operate).

where k is the gross profit margin. For example, if the firm sets a 20 per cent (of its A VC) as its profit margin we have

(1 + k) = 1 + 0. 20 (e / e – 1)

Theory of the Firm

Solving for ׀e׀ we find that the elasticity of demand is 6.

Thus setting a gross profit margin is tantamount of estimating the price elasticity of demand and then applying the marginalist analysis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In summary average-cost pricing reduces to marginalism in a different vocabulary, if the goal of the firm is long-run profit maximisation and the AVC is constant over the range of output which is relevant for pricing. Both these assumptions are explicit in average-cost ‘theories’ of pricing. Hence average-cost pricing does not provide a new theory of the firm and the claim of average-cost theorists that firms resort to average-cost pricing because they do not know their demand elasticity with certainty in the long run, is not a valid argument, because elasticity considerations are wrapped up in setting the gross profit margin.

It is commonly observed that multiproduct firms set a lower mark-up on commodities which have close substitutes, while the mark-up on commodities which have no close substitutes is typically high. These differential mark-ups show that firms know from experience the responsiveness of their customers to the prices of their different products. Although they may not have heard the term ‘elasticity’, the charging of different mark-ups implies their awareness of the reactions of their customers to their prices, and of course this is exactly what the measure of elasticity is devised for by economists.

This behaviour, of setting low mark-ups for products with close substitutes and high mark-ups for commodities with few substitutes, is predicted by the average-cost rule of pricing. Thus this rule reflects implicit considerations of demand elasticities.

How then can we explain the wide application of the average-cost pricing, practices in the modern business world? Several reasons can be put forward to justify the average- cost routine of pricing.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Firstly, average-cost pricing is easier to apply, because the concepts it involves are familiar to businessmen and accountants, while the concept of elasticity is not perhaps understood by the average businessman.

Secondly, average-cost rules facilitate price-setting in multiproduct firms. In these firms acquisition of information on price elasticities for all products is both difficult and costly. The application of general costing margins to the various products becomes a routine which is easy to apply and yields on the average the target level of profit that the firm sets for its overall operation.

Thirdly, trade associations often publicise information of costs of individual product lines, and sometimes go so far as to develop standard cost accounting methods for their members. Use of such information or standard cost accounting techniques is bound to lead to similar prices (for broadly similar products) and hence to a tacit collusion, which co-ordinates the market mechanism.

Fourthly, even without trade associations, average-cost rules of pricing secure ‘orderly working’ of the market, in that firms get used to these rules and learn to anticipate fairly accurately the reactions of competitors to changes in the environment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In conclusion, we can say that average-cost rules of pricing are useful for avoiding uncertainty and to ‘co-ordinate’ the market. But the evidence of constant A VC (over the relevant ranges of output) strips the average-cost ‘theory’ of its essence as a new theory of long-run profit maximisation different from marginal analysis . Average-cost pricing practices should thus be interpreted as routine rules-of-thumb, which are adopted in the real world because they are useful as a market coordinating device, but cannot explain the motivations-goals and hence the decision-making of firms.