Management is the process under taken by one or more individuals to coordinate the activities of others to achieve results not achievable by one individual acting alone. A manager is a person in an organisation who is responsible for the work performance of one or more other persons. Serving in positions with a wide variety of titles (such as supervisor, team leader, division head, administrator, vice-president and so on) managers are persons to whom others report.

These other people, usually called direct reporters or subordinates, and their managers are the important and essential human resources of organisations. Their jobs are to use organisational resources like information, technologies, materials, facilities and money to produce goods and services that the organisation can provide to its customers.

Every manager’s job entails one primary responsibility — to help organisation achieve high performance through the utilisation of all its resources both human and material. In many ways, this means that managers must be able to get things done through other people.

Henry Mintzberg, the well-known management theorist writes, “No job is more vital in our society than that of the manager. It is determining whether our social institutions serve us well or whether squander our talents and resources.” Effective managers utilise organisational resources in ways that achieve both high performance outcomes and high levels of satisfaction among people doing the required work.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

People in organisations perform many different jobs that, when added together, should result in the production of high quality finished goods or services. The division of work is the process of breaking up large tasks such as manufacturing a motor car) and assigning smaller tasks (such as building the engine or the body) to individuals and groups. Once formed, however, this division of work must be well coordinated if a common purpose is to be achieved.

Division of labour concerns the extent to which jobs are specialised. Managers divide the total task of the organisation into specific jobs having specified activities. The activities define what the person performing the job is to do and to get done. For example, the activities of the job “accounting clerk” can be defined in terms of the methods or procedures required to process a certain quantity of transactions during a period of time.

Other accounting clerks could use the same methods and procedures to process different types of transactions. One could be processing accounts receivable; the others process accounts payable. Thus, jobs can be specialised both by method and by application of the method.

Management’s most important organising responsibility is to design jobs that enable people to perform the right tasks at the right time. In fact the ability to divide overall tasks into smaller and specialised tasks is the chief advantage of organised effort.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Optional:

All organisations consist of specialised jobs — people doing different tasks. A major managerial decision is to determine the extent to which jobs will be specialised. Historically, we have seen that managers will tend to divide jobs into rather narrow specialities because of the advantages of division of labour.

Two such advantages are as follows:

1. If a job consists of few tasks, one can quickly train replacements for personnel who are terminated, transferred, or otherwise absent. The minimum training effort results in a lower training cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. When a job entails only a limited number of tasks, the employee can become highly proficient in performing those tasks. This proficiency can result in a better quality of output.

The gains derived from narrow divisions of labour can be calculated in purely economic terms: As the job is divided into even smaller elements, additional output is obtained. As long as the relative increase in output exceeds the relative increase in costs of performing the smaller job elements, increases from specialisation result. However, at some point, the costs of specialisation (labour and capital) begin to outweigh the increased efficiency of specialisation (output), and the cost per unit of output begins to rise.

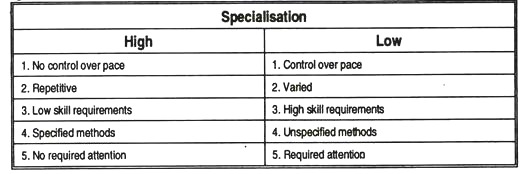

Specialisation, or division of labour at the job level is measured in relative terms. One job can be more or less specialised than another.

In making comparisons of degrees of specialisation, it is useful to identify five aspects that differentiate jobs:

1. Work pace:

The more control the individual has over how fast he must work, the less specialised the job.

2. Job repetitiveness:

The greater the number of tasks to perform, the less specialised the job.

3. Skill requirements:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The more skilled the jobholder must be, the less specialised the job.

4. Methods specification:

The more latitude the jobholder has in using methods and tools, the less specialised the job.

5. Required attention:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The more mental attention a job requires, the less specialised it is.

If we can re-examine the job specialisation continuum, we can identify the specific characteristics of jobs that are relatively high or low in specialisation.

The principle of specialisation of labour has been the traditional guideline for managers when determining the control of individual jobs. In recent years, management’s attention has been directed to alternative ways of designing jobs that focus on teams doing work rather than on individuals doing the same. The automobile industry in particular has emphasised the importance of designing jobs that are performed in the context of teams rather than by individuals.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is a level-by-level arrangement of managers in order of increasing ‘authority’ from bottom to top. It clarifies the performance accountability of every worker to a higher-level manager. A manager’s authority, in this sense, is the right to assign tasks and direct the activities of subordinates in ways that support accomplishment of the organisation’s purpose.

All managers must decide what work they should do themselves and what should be left for others. Herein lies the importance of delegation, the process of distributing and entrusting work to other persons.

Responsibility, authority, and accountability are foundations of effective delegation as described in the following process:

(i) The Manager Assigns Responsibility:

The manager indicates to another person what work or duties he (she) is expected to do. This creates responsibility, the obligation of the other person to perform assigned tasks.

According to the classical approach, management has the following responsibilities:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Planning the work by pre-determining the expected quantity and quality of output for each job;

(b) Organising the work by specifying the appropriate ways and means to perform each task;

(c) Leading and influencing others to engage in work behaviours to achieve the results desired;

(d) Controlling the work by:

(1) Selecting and training qualified individuals,

(2) Supervising the actual job performance, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(3) Verifying that actual quantity and quality of output meet expectations.

At the work level, the responsibilities of management are defined in functions — planning, organising, leading and controlling.

(ii) The Manager Grants Authority to Act:

Along with the assigned tasks, the right to take necessary actions (such as to spend money, direct the work of others or use resources) is granted to the other person. This is authority, the right to act in ways needed to carry out the assigned tasks. Authority is legitimate form of power in that it accompanies the position, not the person. That is, the nature of authority in organisations is the right to make decisions and expect compliance to these decisions.

(iii) The Manager Creates Accountability:

In accepting an assignment, a subordinate takes on a direct obligation to the manager to complete the job as agreed upon. This is accountability, the requirement to eventually answer back to the manager for performance results.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A classical principle of organisation warns managers not to delegate without giving the other person sufficient authority to perform. When the authority delegated is not equal to the responsibility created, the result is reduced subordinate performance, confusion or conflict — or all these.

In this context, we may refer to the famous authority-and- responsibility principle — authority should equal responsibility when work is delegated from a superior to a subordinate.

A common managerial mistake is the failure to delegate. This may be due to a lack of trust in others, or it may lead to personal inflexibility in getting things accomplished. Whatever the reasons, failure to delegate can be damaging. It overloads the manager with the work that could be done by others. It also deprives others of many opportunities to fully utilise their talents and thereby experience greater satisfaction. And it denies the organisation the full value of the experience and knowledge of these others can apply to problem-solving.

Empowerment, giving others authority to act and make decisions on their own, is an increasingly popular theme in today’s workplace. Delegation and empowerment are highly valued management approaches in progressive organisations.