Here we detail about the three motives for liquidity of money by Keynes.

(i) Transactions Motive:

People and firms do not need money for its own sake, but because it can fetch them the necessary goods and services. In other words, money is demanded because it is a good medium of exchange.

There is a gap between the receipt of wages, salaries or incomes and their expenditure. Not only individuals and households need money to meet daily transactions, but business firms also need it to meet daily requirements like payment of wages, purchase of raw materials and to pay for transport etc. The demand for money for transaction purposes depends upon income and the general level of business activity and the manner of the receipt of income.

If everyone received income in cash and simultaneously paid it in cash, there would be no need for holding cash balances, but that is not the case in actual practice. Individuals do not receive money income as frequently as they make payments; lot of time, therefore, elapses between the receipt of income and its expenditure. Thus, as a general rule, we may say that the transaction demand for money is income-elastic and may be expressed as Md = ƒ(Y), where Md is the transaction demand for money and ƒ (Y) denotes it to be the function of income. The influence of interest rate is much less or insignificant.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, it may not always be true to say that transactions demand for money is not very responsive to changes in the rate of interest. It may be so at a relatively low rate of interest, but becomes increasingly responsive at relatively high rates of interest. In fact, it may be understood that the need to bridge the gap between income and expenditures and to finance day-to-day transaction, is not the only reason that gives rise to transactions motive for holding cash balances.

No two persons have identical time patterns of payments and few find their total payments for any month evenly distributed over the period. As a general rule, the average money balances, a person or firm must hold over time for transaction purposes declines as the frequency of his receipts rise. Again, over time the amount of money held will tend to increase to the extent the volume of transactions increase.

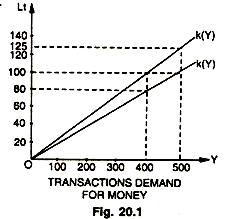

The actual growth in the total volume of transactions has been accompanied by a growth in the size of the GNP or income of the economy and therefore, as a first approximation, the relationship between transaction balances and income level may be taken as linear. This may be expressed in the form of an equation: Lt = k (Y), in which Lt is the money balances held for transaction purposes which depends upon the level of income (Y) with k assumed to be 1/4 that is, if the income is Rs. 400 crore, 100 crore will be required for transaction purposes (because k = 1/4). The size of k, however, depends on institutional and structural conditions within an economy. This relationship is shown in the Fig. 20.1.

In Fig. 20.1 if k is 1/4, Rs. 100 crore denote L, out of Rs. 400 crore. If k is 1/5, then Rs. 80 crore will denote Lt out of Rs. 400 crore. If, however, the income is Rs. 500 crore and k is 1/4 then Lt will be Rs. 125 crore. It shows that changes in the transaction balances (Lt) are the result of changes in Y rather than changes in k.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may also be noted that the transactions needs of individuals and business firms could be financed by liquidating at the appropriate time—real assets or financial assets. The reason why individuals or business firms hold assets againstcash when cash is more convenient to hold, is that there is a 100 cost of holding idle cash balances. It may be called an 80 opportunity cost.

It is the interest income foregone by not 60 holding interest bearing assets or securities and it can be 40 measured by the interest rate paid on financial assets orsecurities. Therefore, as long as the rate of interest paid on assets or securities is greater than zero, no individual or business firm will hold cash balances to meet transactions requirements (provided the cost of liquidating the assets into cash called transfer cost does not exceed the interest payment).

When, however, the interest payment on these assets is not large enough to cover the transfer or transactions cost (and to compensate the asset holder for any inconvenience caused during the transfer process), no individual or business firm will hold financial assets to meet the transactions requirements. Therefore, it is the existence of such costs along with the gap between income and expenditures which also give rise to the transactions demand for money. The influence of interest rate and transactions cost on transactions demand for money can be easily explained.

Let us suppose that the transaction cost for liquidating interest-bearing assets is fixed at 4% of the market value of the asset being liquidated (for example, it costs Rs. 4 to liquidate a bond whose market value is Rs. 100). Now, when the rate of interest is also 4% or less, the cost of liquidating assets equals or exceeds the interest income on asset and it is, therefore, more safe to hold money to meet Lt.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We may say that Lt is completely interest inelastic at interest rate which are equal to or below the transactions cost, i.e., any increase in the interest rate will not induce a movement from cash into interest-bearing assets.

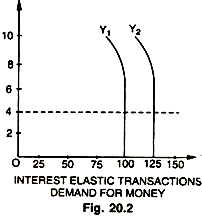

If, however, the rate of interest is higher than 4%, interest income earned on financial assets exceeds the transactions costs and there is a clear incentive to move out of cash into interest- bearing assets and the higher the rate of interest rises, the greater the inducement to move into interest-bearing assets. Therefore, we can say that L, becomes highly interest-elastic as the interest rate rises beyond transactions cost. Therefore, it is said that L, may not be very responsive to r at low rates of interest but. is very responsive at high rates of interest as shown in the Fig: 20.2.

In Fig. 20.2 if Y is Rs. 400 crore and K 1/4 then Lt is Rs. 100 crore as shown by the curve Y1. This figure of Rs. 100 crore holds true as long as the rate of interest is not above 4%, for example, As the rate rises above 4%, the figure shows that Lt for money becomes interest-elastic, showing that given the cost of switching into and out of securities, an interest rate above 4% is sufficiently high to attract some amount of transactions balances into securities. For an income level of Rs. 500 crore, the Lt curve shifts to Y2, (given K = 1/4), but again slopes backward beyond the rate of interest of 4%.

It is rather difficult to generalize on the interest elasticity of the transaction demand for money for the economy as a whole. Most economists generally agree that in actual practice, there is some rate of interest at which the Lt for money for the economy as a whole begins to slope backward, as shown in Fig. 20.2. This means that our equation for transactions demand should become: Lt = f (Y, r) and there is no longer a simple linear relationship between Lt and Y. Hence, the transactions demand for money is a function of both primarily of income and then the rate of interest, specially when it is very high.

(ii) Precautionary Motive:

Individuals, households and business firms find it a good practice to hold money than what is needed for transactions purposes. They hold more money because they want to take proper precautions against unforeseen future contingencies like sickness, unemployment, accidents, fire, old age etc.

An individual who goes shopping will keep more money than what he thinks proper for planned purchases. How much cash a person will hold on account of such unforeseen events will depend upon his psychology and his views about the future and the extent to which he wants protection or insurance against such events. Like individuals, business firms also hold cash to safeguard against future uncertainties.

The cash balances held on account of precautionary motive will differ with individuals and business firms, according to their degree of confidence, wave of optimism or pessimism, access to credit and finance and the facilities for the quick conversion of illiquid assets like bond and securities into cash. As long as individuals and business firms have an easy access to ready cash, the precautionary motive to hold money will be relatively weak.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This type of demand for money is also determined by income and the general level of business activity. Keynes has taken the transaction and precautionary demands for money together, as they both are income determined. Thus, the precautionary demand for money according to Keynes is also income-elastic, it is expressed as Mp = ƒ(Y), where Mp is the precautionary demand for money and ƒ (Y) denotes it to be the function of income. Since both the transaction and precautionary motive are income-elastic, we merge them together (Mt + Mp) and show them as M1 = ƒ(Y).

According to W.W. Haines the precautionary demand for money is influenced by factors like the size of assets, availability of insurance, expectations of future income, availability of credit and the efficiency and safety of financial institutions in making interest-earning assets available. Precautionary balances and their size is determined by the size of the assets owned by firms and individuals.

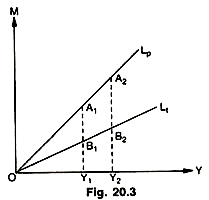

In fact, there is a direct relation between the size of the assets and the holding of cash for precautionary purposes. Again, provision of insurance funds may reduce the necessity of keeping more balances for precautionary purposes. If the units— individual or firms expect their future income to go up and there is easy availability of credit, financial institutions providing facilities of liquidity covertion of securities etc.—then there may not be much need to hold precautionary balances. Like the transaction demand for money, the precautionary demand for money balances also slopes upwards from left to right as shown fig 20.3.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 20.3 Lt is the demand for money for transaction purposes and Lt shows the demand for money for precaution purposes. At Y1 level of income Lt = B1 Y1 and Lt = A1B1. Therefore, Lt at Yt = Lt at Y1 + Lp at Y1 = B1Y1 + A1B1 = A1Y1. Similarly at higher income Y2 – Lt= B2Y2 and Lt = A2B2, therefore, Lp at Y2 = Lt at Y2+ Lt at Y2– B2Y2 + A2B2 = A2Y2.

Although the major influence on precautionary balances, according to Keynes’ position, is that of income yet the influence of the rate of interest cannot be underestimated, because at low interest it is more attractive to hold cash than assets. But there is an inverse relationship between the rate of interest and the holding of precautionary balances, that is. Lp = ƒ(Y. r). As such, it may be concluded that both the transactions demand and precautionary demand for money balances is a function of the level of income (Y) and to some extent the rate of interest (r).

(iii) Asset and Speculative Motive:

Keynes emphasized speculative demand for money as he felt that people kept cash to take advantage of the rise and fall of prices of bonds and securities. It is this demand for money which plays a vital role in the functioning of the economic system, for it is through such a demand for money that prices of fixed income-yielding assets (bonds and securities)- are affected and the rate of interest changes. The speculative demand for money arises on account of the uncertainty regarding the future rate of interest. The individual investors are not sure of the terms and conditions on which debts owned can be converted into cash.

Suppose one expects a fall in the prices of bonds, one will like to hold more cash with a view to spending it in future, when prices actually fall. In this way, individuals protect themselves from possible losses. Similarly, people purchase bonds in anticipation of a rise in their prices. This is called speculative demand for money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Speculative motive is different from other motives as the sole object of holding money under it is to earn profits by “knowing better than the market what the future will bring.” These speculative holdings are specially sensitive to changes in the rate of interest. It is the uncertainty regarding future market rates of interest on different bonds and securities of varying lengths that enable people to do speculation and if their guesses regarding future turn out to be true, stand to gain.

The speculative demand for money is determined by highly psychological factors, as it depends on speculators’ expectations regarding the future rate of interest. But no one knows with certainty what the future rate of interest will be. It is this “uncertainty as to the future course of the rate of interest which is the sole intelligible explanation of this type of liquidity preference”. On account of uncertainty everybody forms his own estimate about the future rate of interest based on expectations.

There are some speculators, ‘the bulls’, who expect that prices of bonds and assets to rise and the rate of interest to fall, while other group of speculators, the ‘bears’, expect the rate of interest to rise and prices of bonds and assets to fall. The stock exchange market strike a balance between the opposite group of expectations. Under the circumstances where there is no uncertainty, no basis would exist for liquidity preference for the speculative motive.

That is why in the classical theory resting upon static assumption no importance is given to speculative motive because the element of uncertainty is ruled out of the theory. It is here that Keynes’ theory differs in a fundamental sense from the classical theory of interest. “By assuming a kind of knowledge about the future which we do not and cannot possess, the classical theory rules out the liquidity preference for the speculative motive and with this, outgoes the basis for a theory of interest.”

The speculative demand for money introduces a dynamic element in an analysis of the general price level and the volume of employment through a relationship between the current and prospective rates of interest and profitability of investment. If the total quantity of money remains unchanged, speculative transactions affect output and employment by changing the rates of interest.

The size of the cash for speculative motive that will be held will be determined by the future changes in the rate of interest rather than by the current rate of interest. Thus, speculative demand for money is interest- elastic and is expressed as M2 = f(r), where M2 is the speculative demand for money and fir) denotes it to be the function of the rate of interest.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, we find that the speculative demand for money—an integral part of the demand for money in Keynesian theory—represents a distinct break with Classical theory. The main feature which distinguishes this demand from the two categories considered previously (Lt and Lp) is that it represents demand for money to hold as an asset. The asset demand for money is related to the decision-making by persons and firms regarding the forms of assets in r which their savings are accumulated.

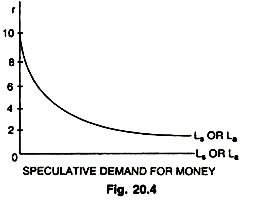

The asset demand reflects a portfolio type of decision concerning the holding of wealth in three possible types of assets—money, bonds and goods. Such a portfolio decision of Individuals and firms concerning the holding of idle balances or other assets depends on the accumulated wealth (w), rate of interest (r), uncertain future (Ur) and the attitude of people towards risk and income, that is, the speculative or asset demand for money can be shown symbolically as : La – ƒ(r, Ur, w). Given the amount of wealth and the uncertainty regarding future the asset demand for money is related inversely with the rate of interest as shown in the Fig. 20.4.

The Fig. 20.4 shows that the higher the rate of interest, the smaller the amount of assets that wealth-holder choose to hold in money form. At high rates of interest, the curve shows that they will hold no money in speculative balances. At a rate of 10% or higher the speculative demand coincides with vertical axis—the speculative demand for money is zero. At this rate no one likes money to bonds.

At the other end of the curve speculative demand becomes perfectly elastic. This occurs at the rate of 2 per cent, a rate so low that wealth-holders believe that it can go no lower. Holding bonds instead of money at this low rate means certain capital loss. This part of the curve is called “liquidity trap”.