Read this article to learn about the situation of monetary policy during depression and inflation.

Monetary Policy During Depression:

Depression is characterized by low marginal efficiency of capital on account of falling prices, incomes, output and employment and the resulting uncertainties.

It is a period of low interest rates and unusually high liquidity preference.

The aims of monetary policy during depression are to offset the decline in velocity of money, to satisfy demands for precautionary and speculative motives; to strengthen the cash position of banks and non-bank groups; stimulating lending for investment and consumption purposes; bringing down the structure of interest rates with a view to encouraging investments, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The cheap money policy of bringing down the rate of interest is followed with a view to increasing aggregate demand, using excessive saving for development or discouraging them, stimulating the prices of securities and confidence of security market. Lowering interest rate is easier than the wage reduction: it also stimulates consumption by encouraging higher purchase, installment buying and credit.

Some Keynesians even went to the extent of advocating its application in poor economies, though Keynes himself did not favour its extension in such economies for different reasons. A cheap money policy of low interest rates in poor economies may discourage savings and may not promote investments or efficient allocation of resources.

It has been argued by some that monetary policy during depression has little scope ; for it fails to pull the economy out of the depths of depression. We find that rates of interest are already very low during depression and cannot be depressed further.

Injections of cash and other liquid securities into the economy are absorbed by firms, banks and individuals in strengthening their liquidity position, in changing from risky and illiquid assets to less risky and more liquid ones, on account of a general wave of pessimism and uncertainty with which future is beset. Under these circumstances, businessmen are scared away by the rapidly depleting profit margins.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Even if it is assumed that the central bank is able to lower the rate of interest, the effect on investment may be negligible because the marginal efficiency of capital continues to be low. Businessmen borrow when business is expanding and not when it is declining.

Low rates of interest cannot make unwilling and nervous borrowers to borrow. One can take a horse to water but cannot make it drink. Even if a lowering of interest rate encourages investment there is a minimum beyond which rate of interest cannot be lowered by increased money supply.’ Thus, monetary policy pursued during depression is rendered almost ineffective and helpless.

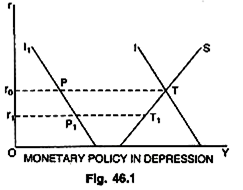

Even if the central bank is able to follow cheap money policy it has hardly any significant effect on the aggregate spending. The gap between saving and investment instead of being bridged is widened because the fall in investment continues on account of adverse business expectations. Even if a cheap money policy is pursued during depression with the expectation that the rate of interest will decline the gap between S and I is not covered or plugged and the deflationary situation continues as shown in the Fig. 46.1.

In this diagram, there is a shift in the investment curve (from its equilibrium position) from I to I1 on account of deflationary conditions. At r0 interest rate, saving exceeds investment by PT. A decline in interest rate from r0 to r1 raises investment, no doubt and reduces savings, but the deflationary gap still continues, though it is reduced to P1T1 from PT at interest rate r1. Moreover, it is not possible to reduce the rate of interest below a certain level (say Or1) on account of the obstacle placed by liquidity trap. This brings forth serious limitation of monetary policy as an anti-depression measure.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, it would be a gross mistake to dispense with monetary policy as irrelevant and useless, for cheap credit policy does affect private investment and demand for durable consumer goods. Whether it be an advanced or an underdeveloped economy, monetary policy is a good and necessary adjunct to other measures for maintaining full employment.

In this connection, Prof. K. Kurihara remarks, “Thus, in the industrially and financially less developed countries credit and banking policies are much more than a mere brake on undue credit inflation. Even in industrially advanced countries there is scope for effective anti-depression credit (monetary) policy as long as real estate credit, consumer installment credit and other particular types of credit remain restricted by high interest rates. Even if credit policy is incapable by itself of turning the tide of depression it can increase overall liquidity via open market operations and other conventional methods, thereby creating the monetary atmosphere necessary for the successful operations of more effective measures of fiscal and other policies.” Therefore, it is wrong to remark that monetary policy is not as potent a deflation-offset as it is an inflation offset.

Monetary Policy During Inflation:

Inflation is characterized by high marginal efficiency of capital on account of rising prices, incomes, output and employment. There is a general wave of optimum and business activities expand rapidly; as such, more cash is released by banks making additions to consumers’ income and outlay. Traders faced with reduced stocks of goods and continuously rising demand make frantic efforts for getting and holding additional stocks they consider as appropriate.

The improved prospects of business and the high values of securities on the stock exchanges make the banking authorities willing to expand credit. This will be used in making additions to fixed capital, plant and machinery. One might expect that this will go on forever. Unfortunately, this is not what happens. Both consumer spending and investment spending reach a high pitch making credit conditions extremely tight. Banks find it difficult to cope with the increased demand for credit.

Under such circumstances, the aims of monetary policy are to slow down the rate of expansion of money to effect the increase in its velocity, to reduce the volume of liquid assets, to reduce consumption and spending’s by means of higher interest rates. Such a monetary policy during inflation is necessary to meet the ends of stabilization and to avoid a sudden collapse. The idea is to check inflation and level off the boom conditions and not to plunge the economy into depression.

The effectiveness of monetary policy during periods of inflation is much greater. It is easier to raise interest rates than to lower them, and they can be raised as high as the monetary authorities wish. This is followed by open market operations to curtail the liquidity of bank and non-bank groups, thereby further reducing lending and investment. Moreover, margin requirements and consumer credit conditions may also be tightened. Even then, if consumption and investment spending’s are not reduced there remains the power to raise reserve requirements to prevent further expansion of bank credit.

Thus, monetary policy can be fairly effective, if applied quickly and continuously in preventing booms from developing into inflation. However, experience has shown that monetary policy has not been very successful in averting inflationary pressures. This lack of success has been partly the result of factors inherent in monetary policy (as is the case in depressions) and partly by various neutralizing effects.

The policy may be rendered ineffective on account of factors more or less extraneous to the monetary policy; for example, if powerful forces are at work, inflation becomes self-invigorating despite all efforts at credit control. The effectiveness of monetary policy during inflation will depend upon changes in the velocity of circulation of money because these changes sometimes may completely neutralize the restrictions imposed by the central bank on the supply and cost of money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There may be sale of government securities and the rapid growth of financial intermediaries in the post-war period is another discouraging development which has weakened the conventional monetary controls of the central banks. Their activities which include insurance companies, housing societies, savings and loan associations, financial houses—sometimes mobilize savings from public and advance loans in turn.

Sometimes, the debt management operations and discriminatory and uncertain effects of monetary policy on different sectors of economy render it ineffective. It is impossible for the policy makers to ignore the differential effects and aspects of tight money policy on different sectors of the economy particularly when they are not certain of exactly what a suitable monetary policy is under a given situation. All these limitations account for the ineffectiveness of monetary policy during inflation.