International Trade: Features, Comparative Advantage and Benefits!

Features of International Trade:

There are some special features of international trade so we need a separate explanation.

First, since there is no international currency, we must deal with the problem of exchange rates.

Secondly, countries can and do impose restrictions on trade or barriers to trade that individual companies would be unable to impose without government support. Examples are tariffs, quotas, and subsidies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thirdly, inputs, especially labour, are not as mobile internationally as they are domestically.

Finally, there are differences in demand patterns and marketing considerations across national borders.

Managers must be aware of these factors and their impact on their market environment. Our primary task here is to explain the reasons why nations trade with one another, focusing on the gains from trade due to each nation’s special attributes, such as natural resources, educational levels, and transportation networks.

The international immobility of certain inputs and the differences in demand patterns among nations will be especially important factors in the context. Thus we examine the restraints on trade imposed by governments. We will consider tariffs, quotas, “voluntary” export restraints, and international commodity agreements.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Nations trade with one another for the same reason that individuals trade with one another: mutual gain from specialisation. Today, few individuals and few nations produce all of the goods that they consume. Individuals have different abilities and domestic environments, and all learn special skills that permit them to earn an income to buy goods and services supplied by others.

This specialisation leads to higher levels of consumption for everyone. A nation has an absolute advantage in the production of a product or service when that person or nation can produce more units of the product or service than another country while using the same amount of inputs (such as time). The opposite of an absolute advantage is an absolute disadvantage.

While few nations have an absolute advantage in the production of goods or services over others even for just one product or service, everyone faces a choice of how to use their skills and abilities. Fortunately, an absolute advantage is not necessary to gain from trade.

A country need only determine what it is capable of doing best relative to the options available to it. Nations make the same choices. These decisions depend on the nation’s endowments of labour, natural resources, and infrastructure.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Comparative Advantage in Production:

Nations like individuals maximise their potential well-being and consumption by producing goods and services that they are especially well- suited to produce. To gain from trade, nations do not need an absolute advantage relative to other nations but a comparative advantage.

A comparative advantage is the production of those goods and services that individuals and countries produce more efficiently relative to other possible goods or services. And a comparative advantage in the production of one commodity implies a comparative disadvantage in another.

Economist David Ricardo developed the comparative advantage concept to explain the basis of trade from the supply-side. The following example nicely summarises Ricardo’s argument. Following Ricardo let us assume that only two countries exist: England and Portugal. There is only one input: labour.

The two countries can each produce both the goods: clothing and wine. The countries can trade the two goods freely with one another but labour is immobile internationally. Ricardo assumed that technology does not change as a result of trade, and that the only difference in the cost of producing the two products is the amount of labour used.

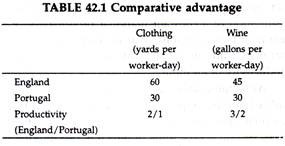

Table 42.1 shows specific production functions for the two countries. In this example it takes one worker-day in England to produce 45 gallons of wine and one worker-day to produce 60 yards of clothing. In Portugal, wine production is 30 gallons per worker-day and clothing production is 30 yards per worker-day.

This example assumes that labour in England is more productive than labour in Portugal in producing both products. This means that England has an absolute advantage in the production of both the goods, so it may apparently seem that trade between the two countries would lead England to produce both goods and Portugal to produce nothing.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, a by comparing the relative productivity of labour in the two countries, we can see that England has a comparative advantage in clothing.

For example, a worker in England can produce twice as many clothing (60 yards versus only 30 yards) as the Portuguese worker can, while the England worker’s advantage in wine production is only 45 gallons to 30 gallons, or 3 to 2. Compared to the Portuguese worker, the English worker is relative better at making clothing than wine, even though the English worker has an absolute advantage in producing both the goods.

Given these production functions, England has a comparative advantage in textiles. Portugal has an absolute disadvantage in both products but a comparative advantage in wine production. Portugal must choose between the production of wine and clothing. Since Portugal’s absolute disadvantage relative to England’s is less when producing wine, Portugal has a comparative advantage producing wine.

Mutually Beneficial Trade:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ricardo has demonstrated the advantage of trade by looking at the opportunity cost of having both Portugal and England produce both wine and clothing.

We may now show that the two countries will be able to increase their levels of consumption of both goods by specialising. England will use its comparative advantage and specialise in producing clothing. Portugal will use its comparative advantage to specialise in producing wine.

Numerical Example:

Assume that the supply of labour is fixed in both countries. Each country must allocate its labour to maximise its overall production and consumption possibilities. Since one worker-day in England yields either 80 yards of clothing or 80 gallons of wine, England must give up 80 yards of clothing for every 80 gallons of wine it produces. The 80 yards of clothing is the opportunity cost of producing 80 gallons of wine.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since there is no known way of converting clothing directly into wine, the use of labour to produce wine reduces the amount of labour available to produce clothing. The internal ratio showing the trade-off of yards of clothing to gallons of wine in England is therefore equal to 60 units/60 units or 1/1.

In Portugal this ratio is 30 yards/30 gallons, or 1/1; that is, the opportunity cost of 1 gallon of wine in Portugal is 1 yard of clothing. Portugal would be willing to trade some of its wine for England’s clothing as long as it would receive more clothing by trading wine for clothing than by producing clothing itself.

England would use the same reasoning in deciding whether to trade textiles for wine. By producing textiles and selling some of them to Portugal for wine, it could increase its overall consumption of wine and textiles. The incentive to trade will depend on the rate at which the countries trade wine for textiles.

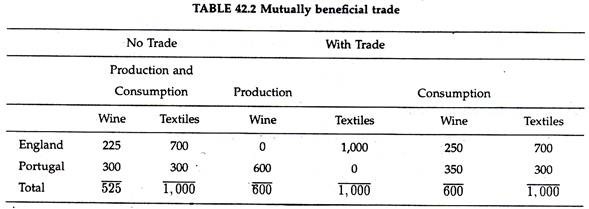

Let us consider what happens if the price ratio for trade is 1 gallon of wine for 1.2 yards of textiles. Table 42.2 summarizes the following situation. Assume that at full capacity England can produce 1,000 yards of textiles and Portugal can produce 600 gallons of wine. England can convert textiles to wine by producing wine while reducing its output of textiles.

The trade-off is 4/3 yards for 1 gallon. For example, at a production level of 700 yards, it would have 225 gallons of wine. If it instead produced 1,000 yards of textiles and sold 300 yards to Portugal, it would have 700 yards left over and 250 gallons of wine.

Portugal could produce 600 gallons of wine by using all its resources fully. It could instead produce 300 gallons of wine and 300 yards of textiles.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By producing 600 gallons and selling 250 to England, it would have 350 gallons of wine and 1.2 x 250, or 300, yards of textiles. By trading, both countries have done better than they would have done without trade. In this example, they have produced an extra 75 gallons of wine with the same total output of textiles.

We know that within Portugal the trade-off between wine and textiles is 1 to 1. In England, it is 1 to 4/3. Portugal would never trade 1 gallon of wine to England for less than 1 yard of textiles. England has to give up 4/3 yards of textiles for every gallon of wine it produces. England would not be willing to give up more than 4/3 yards of textiles to purchase a gallon of wine from Portugal.

This simple example suggests that the limits to mutually beneficial trade are between a minimum of 1 yard and a maximum of 4/3 yards of textiles for every gallon of wine. At a trading ratio between these two limits both countries would be better off with trade than in the absence of trade.

Demand Considerations:

The main prediction of the Ricardian theory is that countries with different cost advantages have an incentive to trade. The price at which they trade also depends on demand conditions in each country. As long as the price ratio lies between the limits set by comparative advantage, both countries gain from trade.

In this case both countries increased their consumption of wine. If the trading price of textiles for wine were lower than 1.2 (that is, fewer textiles in exchange for 1 gallon of wine), Portugal would have to give up more wine to consume the same amount of textiles. The lower price would reflect Portugal’s stronger demand for textiles.

It is interesting to note that even if the comparative advantages were the same in both countries, there still might be an incentive to trade. Actual markets are not as homogeneous as suggested by this example.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For instance, people have different preferences for French, Italian, American, and Portuguese wine, which induces international trade among these countries even if the comparative advantage is the same in each country.

There are differences in tastes not only between countries, but within countries. The differences in tastes within countries may be a source of trade. For example, there may be little difference in comparative advantage among European countries in the production of luxury automobiles.

Differences in tastes within each country will lead to both a variety of automobiles purchased in a country and two- way trade in automobiles among such car-producing countries as Germany, France, England, and Sweden.

Incomplete Specialisation:

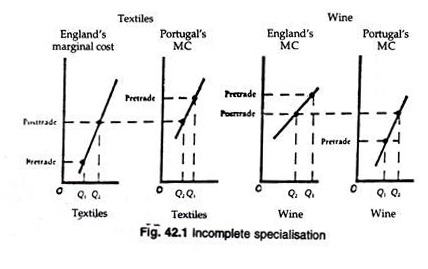

In the wine and textile example we concluded that both countries should specialise in producing only one product. Actually, we do not see complete specialisation in the real world. We had complete specialisation in this example because of the assumption of a constant marginal productivity of labour in both countries. But in reality we expect that eventually there will be diminishing marginal productivity of an input.

With diminishing marginal productivity there will be incomplete specialisation in each country. Incomplete specialisation occurs when a country produces several goods, some of which it also imports. With diminishing marginal productivity the country needs increasingly greater amounts of the input to increase output at the same marginal rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This means that the marginal cost of each additional unit of output is increasing. Fig. 42.1 shows how increasing marginal cost will affect the production of both products in a country. Each country will decide to produce an output level where marginal cost equals marginal revenue.

Fig. 42.1 shows marginal-cost curves for wine and textiles in Portugal and England. The figure indicates the pre trade outputs and an international trade price between the two extremes of marginal cost set by output levels prior to trade. After the two countries begin to trade, they will face the same prices.

England will increase its production of textiles to the point where the trade price equals its marginal cost. It will reduce the production of wine. Exactly, the opposite thing will happen in Portugal: increased wine production and lower textile production.

This analysis can be extended to cover more than two goods. Countries produce a wide range of products subject to different production functions. We expect that a country will export those goods in which it has the greatest comparative advantage and import more of the goods in which it has a comparative disadvantage.

If the country has no effect on the world price, it will set its output level where the marginal cost equals the world price. Countries with a comparative advantage will have relatively lower marginal-cost curves and will produce more output at world prices.

The Balance of Payments:

Just as countries calculate their national income or GNP so as to have a general idea of the domestic level of production, most countries keep a record of their external economic transactions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such a record is known as the balance of international payments. It is a systematic record or statement of all economic transactions between the members of the home country and those of another country or the rest of the world in an accounting year.

In other words, the balance of payments account is a periodic report that summarizes the flow of economic transactions with foreigners. If it thus gives us an overall measure of the flow of goods, services and capital between a country and the rest of the world.

It is a very useful document because it provides information on various important aspects such as the nation’s exports, imports, money lent abroad and earnings of domestic residents on assets located abroad, money borrowed abroad and earnings on domestic assets owned by foreigners, international capital movements, and official transactions by Central Bank and governments.

Balance of payments (BOP) accounts are prepared on the basis of the principles of double-entry book keeping. Thus, like other accounts, balance of payments record pluses (credits) and minuses (debits).

Each entry on the debit (—) side of the ledger is matched by an identical entry on the credit side (+). Any transaction involving outflow of foreign exchange (currency) from a country (such as imports) is recorded as a debit, or minus, item.

In this context one has to remember the following rule: If an economic transaction provides us with more foreign currency, as exports do, it is to be recorded as a ‘credit’ item. If, on the other hand, in economic transaction like an import reduce our stock of foreign currency, it is to be treated as a ‘debit’ item.

For example, Indian import of a Swiss watch is definitely a debit item since it draws down our stock of Swiss franc. In contrast, interest and dividend income on investment received by India from abroad are clearly credit items. It is because, like merchandise exports, they provide us with foreign currencies.

Four Components:

The balance of payments transaction of a country has four components, viz.:

(1) Current account,

(2) Capital account-private and official (government),

(3) Statistical discrepancy and

(4) Monetary movements or official financing (reserve) account. We now have a look at each of the categories.

Current Account:

All transactions—payments and gifts—that are related to the purchase or sale of goods and services in an accounting year are included in the current account.

As a general rule three major types of transactions are included in the current account, viz.:

(i) The exchange (export and import) of merchandise goods (called visible),

(ii) The exchange of services (called invisibles) and

(iii) Unilateral (one-sided and unconditional) transfers.

(i) Merchandise Trade Transactions:

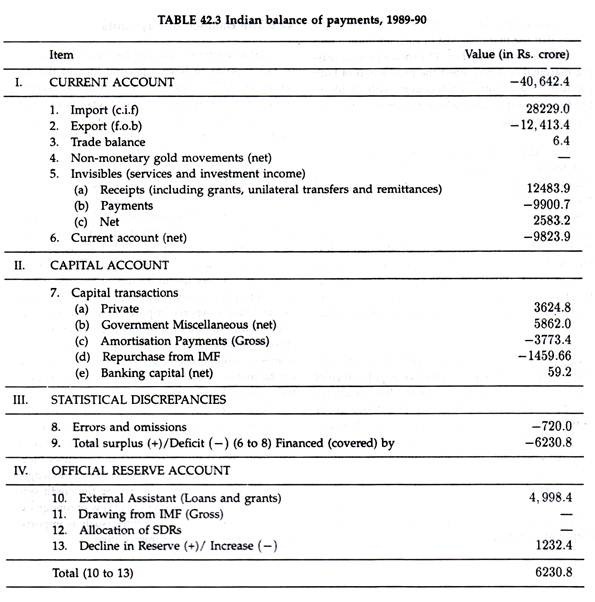

The largest portion of a country’s balance of payments account consists of the exports and import of merchandise goods (called visible export). As Table 42.3 shows, in 1989-90 India imported Rs. 40,642.4 crore of goods and exported only Rs. 28,229 crore. When Indians import goods from abroad, they supply rupees to the foreign exchange market.

This is why imports are recorded as debits in the balance of payments accounts. In contrast when Indian producers export their products, foreigners demand rupees on the exchange market to pay for Indian exports. Therefore, exports are entered as credit items.

Balance of Trade:

The difference between the value of a country’s (merchandise exports and that of imports is known as the balance of (merchandise) trade. If the value of a country’s visible exports falls short of (exceeds) the value of visible imports, it is said to have a deficit (surplus) in its balance of trade.

In 1989-90 India ran a balance of trade deficit of Rs. 12,413.4 crores. It is to be noted that the balance of trade is just one component of a nation’s total balance of payments.

Other things remaining the same, an Indian trade deficit simply implies that Indians are supplying more rupees to the foreign exchange market than foreigners are demanding for purchase of Indian goods.

If the trade deficit were the only factor influencing the value of the rupee on the exchange market, one could anticipate a decline in the foreign exchange value of the Indian rupee. However, various other factors also affect the supply of and demand for the rupee on the foreign exchange market.

(i) Export and Import of Invisible:

In addition to visible (trade) items a country also exports and imports invisibles, which consist of services and investment income. The export and import of various services, called ‘invisibles’ also exert considerable influence on the foreign exchange market. The export of various services such as insurance, transportation, tourism and banking generates a demand for rupees by foreigners just as the export of goods does.

An American business which is insured with an Indian company will demand rupees with which to pay its premiums. When foreigners travel in India or transport cargo on Indian ships, they will demand rupees with which to pay for those services. In a like manner, income earned by Indian investments abroad will cause rupees to flow from foreigners to Indians.

Investment income includes mainly net earnings on investment abroad (that is, earnings of Indian assets abroad less payments on foreign assets in India). These exports of various services are thus entered as credits on the current account.

In contrast, the import of services from foreigners expands the supply of rupees to the foreign exchange market. Therefore imports of invisible services are entered on the balance of payments accounts as debit items.

Travel abroad by Indian citizens, the shipment of goods on foreign carriers, and income earned by foreigners of Indian investments are all debit items, since they supply rupees to the foreign exchange market.

In most modern mixed economies these services transactions are quite substantial. As Table 42.4 shows, in 1989-90 Indian service exports (including grants, unilateral transfers and remittances) were Rs. 12,483.9 crores, compared with service imports of Rs. 9,900.7 crores.

(ii) Unilateral Transfers:

Monetary gifts to foreigners, such as Indian aid to a foreign government (such as the Government of Bhutan) or private gifts from Indian residents to their relatives abroad, supply rupees in the foreign exchange market. These gifts are entered as debit item in the balance by payments accounts. In contrast, monetary gifts to Indian from foreigners are treated as credit item.

Gift in kind create accounting problems. When products are given to foreigners, goods flow abroad. But there is no offsetting inflow of foreign currency —that is, a demand for rupees. Balance of payments accountants handle such transactions as though India had supplied the rupees with which to purchase the direct (unconditional) grants made to foreigners. Obviously these items are also to be entered as debits.

Balance on Current Account:

The balance on current accounts is a much broader term than the balance of (visible) trade. In fact, the balance on current account summarizes the difference between our total exports and imports of goods and services.

The differences between:

(a) The value of a country’s exports of goods and services and

(b) The value of its imports of goods and services plus net unilateral transfers is known as the balance on current account, if the value of a country’s exports is less than (exceeds) the value of its imports plus the unilateral transfers, the country is said to be experiencing a deficit (surplus) on current account transactions. In 1989-90 India ran a (net) current account debt deficit of Rs. 9,823.9 crores.

Capital Account Transactions:

Capital account transactions consists of two broad items, viz.:

(a) Direct investments by Indian in real assets abroad (or by foreigners in India) and

(b) Loans to and from foreigners. If an Indian businessman (investor) purchases a textile plant in Japan, the Japanese seller will want to be paid in yens.

The Indian investor will supply rupees (and demand yen) in the foreign exchange market. Therefore, Indian investment abroad (i.e., capital export from India) is to be entered as a debit item in the balance of payments account. In contrast, foreign investment in India (i.e., capital import) creates a demand for rupees in the foreign exchange market. Therefore, it is entered as a credit item.

Investment abroad is treated as the import of an asset. In fact, from a country’s balance of payments point of view, there is difference between importing ownership of a financial (or real) asset from abroad and importing goods from abroad.

Thus both are to be recorded as debits. Similarly, in a sense, we are exporting the ownership of capital when foreigners invest in India. Thus these transactions are to be recorded as a credit.

Even within a country’s domestic market various transactions are carried out on the basis of credit. When, for instance, an Indian bank makes a loan of Rs. 500,000 to a foreign entrepreneur for the purchase of an Indian machine, the bank is in effect importing a foreign bond.

Since the transaction implies supply of rupees in the foreign exchange market, it is recorded as a debit. In contrast, when Indians borrow from abroad, they are exporting bonds. Since this transaction creates either a demand for rupees on the part of foreign lender (in order to supply the loanable funds) or supply of foreign currency, it is to be entered in India’s balance of payments account as a credit item.

The Office Financing (Reserve) Account:

Governments have to keep reserve balances to make various balance of payments adjustments.

Such reserves take three different forms:

(i) Gold,

(ii) Foreign currencies and

(iii) Special drawing rights (SDRs) with the International Monetary Fund.

Countries suffering from balance of payments deficits, i.e., deficit on their current and capital account balance, can draw on their reserves.

In fact, the official reserve account shows how a deficit in the balance of payments is covered. There are four ways of covering such a deficit, viz., by selling gold, by selling foreign exchange, by selling foreign assets or by borrowing from other countries or IMF. Likewise, a country enjoying a surplus in the balance of payments can build up their reserves of foreign currencies and reserve balances with the IMF, i.e., SDRs.

The official financing account also shows how a surplus in the balance of payments is utilized. In fact, there are three ways of utilizing a surplus, viz., by purchasing gold, purchasing foreign currencies and purchasing foreign assets like the shares of multinational corporations or repaying debt to foreign countries or IMF.

When the world economy was on the gold standard and the government followed a strict laissez faire policy, any adverse BOP was corrected by export and import of gold. Likewise, under the fixed exchange system present during 1944-1971, most countries, faced with balance of payments difficulties, were found to draw on their official reserves (held in the form of foreign currencies, gold and SDRs) to maintain this fixed exchange rate. Countries were selling more to foreigners than foreigners were buying from the accumulated currencies of other nations.

Now the world is on the inconvertible paper currency system and most countries balance their books with government payments or receipts of foreign currencies.

Under the present floating exchange rate system countries normally permit a rise or fall in the foreign exchange value of their currency to bring about equilibrium in the exchange rate market. At times nations instruct their central banks to buy and sell currencies in an attempt to sharply reduce the exchange rate.

These balancing flows provided by governments or central banks are known as ‘official reserve transactions’. The most common way of making such settlements is for countries to buy or sell Government securities.

Balancing the Accounts:

Reflecting the double-entry book-keeping procedures, the aggregated balance of payments account must balance. In fact, any current account deficit is wiped out either by borrowing or by reducing foreign assets. “For”, as RA. Samuelson and W.D. Nordhaus have put it: “it is definitional that what you buy you must either pay for or own for. This means that the balance of international payments as a whole must by definition show a final zero balance.”

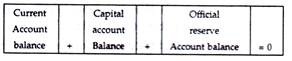

And the following balance of payments identity must hold:

However, it is not necessary for the specific components of the accounts to be in balance. For example, the debit and credit items of the current account need not balance. In other words, specific components may run either a surplus or a deficit. Nevertheless, the overall account or the balance of payments as a whole must balance. This means that a deficit in one area implies a surplus in another.

If a nation is suffering from a deficit in its current account balance, it must generate an offsetting surplus on the sum of its capital account and official reserve amount balances. A deficit in the current account simply implies that a country is buying more goods and services from foreigners than they are selling to foreigners.

Under the present day flexible exchange rate system this excess of expenditures relative to receipts is covered by buying and selling assets from and to foreigners. Methods of Correcting Adverse Balance of Payments There are a number of ways by which a deficit in the balance of payments may be corrected.

The usual methods that are employed by different countries are:

(a) Deflation:

It refers to reducing domestic demand by

(a) Raising bank rate,

(b) Raising tax rates,

(c) Cutting government spending and deficit,

(d) Reducing bank lending.

All these result in a reduction of money incomes and prices through a contraction of the money supply. A fall in prices makes exports competitive: exports which now appear cheaper to foreigners are stimulated. On the contrary imports are reduced because they are now costlier than before.

(b) Devaluation of the Currency:

This refers to the official reduction in the external value of a country’s currency in terms of another currency or gold. As a result prices of imports rises and fall. However, imports will be effectively reduced if the demand for them is sufficiently elastic.

(c) Exchange Depreciation:

This means allowing a currency to fall in value on the foreign exchange market in terms of other currencies. As a result exports become cheaper to foreigners and imports dearer in the home market. One of the advantages of freely fluctuating exchange rates is that they automatically correct disequilibrium in the balance of payments through the free play of international market forces.

(d) Exchange Control:

In general, exchange controls require that the government, rather than the free market, decide the order of priority for the importation of goods and services.

This decision may then be implemented allocating the limited supply of foreign exchange among competing uses. This course of action is open to a country with a fixed rate of exchange and unwilling to devalue its currency. The success of this type of policy depends on a country’s reserves of foreign currency.

(e) Commercial Policy:

It refers to restriction of imports by tariffs, temporary surcharges on import quotas.

Trade Policies:

Despite the expected benefits of increased trade among nations, there is strong international sentiment in favour of restricting trade to achieve specific objectives. Protectionism takes the form of subsidies, export restraints, quotas, and tariffs.

Both quotas and tariffs increase the price paid by Indian consumers. In addition, more resources are used to produce these products than would be if they were produced by the most efficient suppliers.

Tariffs:

A country can and does impose a tariff on imports or exports. A tariff is a tax added to the price of a good when the good crosses the boundaries of the importing country. Export tariffs are relatively rare. While import tariffs do generate revenue, the principal reason for their use today is protectionism.

There are three different types of tariffs: ad valorem, specific duty, and compound duty. An ad valorem tariff is a fixed percentage of the price of the good.

A specific duty tariff is a fixed sum of money per unit of the good (for example, Rs. 1000 per television set). A compound duty combines an ad valorem tariff and a specific duty on the same good. The specific duty tariff is easier to administer because it is quantity-specific and does not depend on determining the appropriate price of the product.

The two types of tariff have essentially the same economic effects.

Economic Effects:

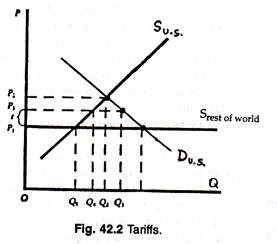

Figure 42.2 shows the effects of a tariff on an otherwise competitive industry. P1 is the prevailing world price for good Q. S is the Indian firm’s supply curve, and D is the demand curve for good Q from Indian consumers.

If there were no world trade, Indian suppliers would meet their country’s demand at price P2. With trade, the Indian domestic price is the same as the world price. If the world price is P1, Indian consumers purchase Q1, and domestic suppliers supply Q0. The difference between Q1 and Q0 is net imports.

If the Indian Government imposes a tariff of t equal to P3 – P1 on imports, the tariff would raise the effective domestic price to P3. For a foreign company to be willing to sell to an Indian company, it must receive a price from consumers that covers the world price plus the tariff. Otherwise, it would sell its output elsewhere.

The higher price of P3 encourages Indian firms to produce a greater output level since they do not pay the tariff. The higher Indian price due to the tariff forces Indian consumers to reduce their quantity demanded of the good to Q3. The Indian government receives the amount of the tariff times the number of units sold as revenue.

Indian output of the good increases. The additional output is not without an opportunity cost to Indian citizens. Here the market supply curve represents the horizontal sum of the marginal-cost curves of all of the Indian firms in the market. The area under the supply curve e represents the sum of the variable cost of producing a given level of output.

In figure 42.2 the area under the Indian supply curve and above the world supply curve shows the additional cost of producing the extra amount of output domestically rather than purchasing it from other countries.

That extra cost comes from resources that have been pulled away from other industries that would use them more efficiently. These other industries must rank higher on the country’s list of comparative advantage. Otherwise, the resources would already be in the protected industry.

Quotas:

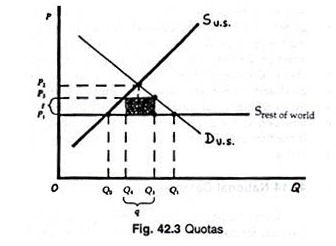

A quota is an alternative to a tariff. A quota is a physical limit on the amount of a good that a country can export to another country during a specified time period. Quotas can have essentially the same effects on domestic prices and output as tariffs have.

However, a quota does not give any revenue to the government imposing it. .While the quota raises domestic prices, the benefits of the higher price go to the foreign firms. The effect of a quota is illustrated in Fig. 42.3.

In Fig. 42.3 we have the same demand and domestic-supply curves as in Fig. 42.2. At the world price, imports equal Q1 — Q0– If the government imposes a quota of less than Q1 — Q0, the domestic price will rise above the world price. For example, in Fig. 42.3 a quota of q will result in a domestic price of P3. Consumer demand will decrease to Q3, while domestic output will increase to Q4 (i.e., Q3 — q).

The government could have set the same domestic price by imposing a tariff of t equal to P3 — P1. With a tariff the shaded area in Fig. 42.3 would represent the revenue going to the government. With a quota the shaded area would indicate the additional profits earned by the importers due to the higher domestic price.

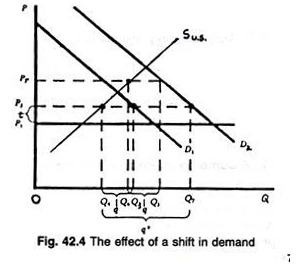

The effect on government revenues is not the only important difference between quotas and tariffs. When there is an increase in demand, quotas impose greater distortions on domestic prices than tariffs do. This point is illustrated in Fig. 42.4.

In Fig. 42.2 and 42.3 the tariff t raises the domestic price above the world price by the same amount as a quota of q. Despite this equivalent effect on domestic price, an increase in demand from D1 to D2 will have a different impact on the domestic price depending on whether the country has imposed a tariff or a quota. Fig. 42.4 shows the effects of an increase in demand with a quota and a tariff.

With a tariff of t the domestic price remains at P3 regardless of the nature and shape of the demand curve. The additional quantity demanded due to an increase in demand from D1 to D2 will be met by increased imports. Imports will now be q.

The same increase in demand to D2 will increase the domestic price if the quota remains unchanged. In Fig. 42.4 a quota of q creates the same domestic price as the tariff t when the domestic demand curve is D1.

When the demand curve shifts to D2 the domestic price rises. This encourages domestic producers to produce more. Consequently there would be a gap between the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied. In this case at the new price P5, domestic output increases to Q6,. The quota fixes imports at q.

Voluntary Export Restraints:

Due to international trade agreements, the developed countries do not use quotas to restrict imports of manufactured goods. Despite the ban on quotas, countries often demand “voluntary” export quotas in place of a threatened tariff or quota. These arrangements are bilateral agreements between two countries and are enforceable by the exporting country.

Export restraints are not as effective as quotas because of the difficulty of controlling imports. For its part, the exporting country does not usually want to control its exports. Companies in that country can often evade the restraints by selling through a third country not subject to the agreement.

International Commodity Agreements:

Countries with extreme concentration of exports in one or two commodities, such as coffee, tin, cocoa, and sugar, may experience sharp fluctuation in earnings from the export of these goods due to unexpectedly large or small harvests or changes in production by other countries.

For many agricultural products an unexpectedly large harvest should lead to sharp drops in market prices. A small harvest should send prices higher. This may sound like a paradox.

Dependence on export revenues and wide fluctuations in market prices has led many export countries to form international commodity agreements with the buying nations. Unlike a cartel, which contains only the producing units and nations, a commodity agreement includes the buyers also.

A commodity agreement can take one of several forms. First, there may be a provision to adjust price to compensate for a change in the quantity demanded. Some agreements attempt to adjust price to maintain relatively stable total revenues.

A second form of agreement involves buffer stockpiles that a central agency buys and sells to smooth out the wide fluctuation in the market price. By buying output and storing it, the central agency keeps the price from falling. The guiding principle is that the agency sells from the stock during years when the quantity supplied is low.

In this way the agency virtually act as a speculator. A third type of arrangement sets minimum and maximum prices. Within the limits the market price prevails. When the market price goes beyond the limits, the limits become the transaction price.

Protectionist Proposals:

There have been arguments made in favour of protectionism. The four common argument are the following: initial support for an infant industry, national defence, anti-dumping and retaliation against unfair trade practices. Behind most of these proposals is the fear that there will be a loss of jobs due to an increase in imports. It is necessary to realise the expected impact on employment and national income.

Infant-Industry Argument:

There is support, especially in developing countries, for new firms seeking protection from larger, established, foreign companies until the new firms can support themselves.

While the ultimate success of a new firm depends on its long-term profitability, it is apprehended that the firm may not be able to convince creditors of its long-term viability without this initial protection. Proponents of this argument stress that firms in the industry will experience significant decreases in their operating costs over time.

At times the infant-industry argument appears to be unscientific in as much as it is put forward in defense declining industries hoping to protect their market position.

Moreover it has been difficult in practice to remove protectionist measures once the industry has become competitive. Firms not only become accustomed to the protected environment, they find it more profitable with barriers to competition than without them. Resources that could be used to improve their competitive position are used instead to maintain the protection for political reasons.

In some countries it may be more efficient to use a subsidy to protect an infant-industry than to rely on quotas or tariffs.

As James Mulligan has suggested “A subsidy acts oppositely to a tax by lowering the production costs of the firm. Subsidies only affect production costs without affecting consumer choice. Consumers do not face higher prices for the good and do not alter their consumption patterns by switching to substitute goods. After a specified time period, the government can end the subsidies. If the firm cannot survive by then, it may never be viable.”

National Defense:

Many industries claim that their products are essential for national defense purposes. It is a fact that if the country does not have a viable industry producing the good, it might not be able to obtain the good in times of war. As Adam Smith pointed out long ago, “Defence is more important than opulence.”

The national security argument suggests that a good would not be available from other countries in time of need, such as during war. No country wants to sell its products to enemies.

During the recent Gulf war, America refused to sell it products to Gulf countries. For any country to be cut off from supplies of essential goods, it would have to be isolated from most of the world. So it is in the Tightness of things to develop domestic industries producing import substitute items.

Anti Dumping Argument:

Via the media we often hear complaints of dumping by foreign firms. Dumping is the selling of goods to a foreign country for a price below that charged to customers in the home country. Dumping is actually an application of price discrimination.

Dumping as Predatory Pricing:

A major argument against foreign dumping hinges on alleged predatory pricing by foreign firms. A firm adapting this pricing practice can lower its price and force less financially solvent firms out of the market. After the departure of these firms, the predator raises prices to recover losses. However, the success of the policy depends on the ability of the predator to maintain barrier to entry after it eliminates its competition.

Retaliation against Foreign Dumping of Goods:

The crux of a policy against foreign dumping is the expectation that retaliation will have positive effects. Retaliation may have a direct effect once a government imposes a retaliatory tax. There may also be an impact dot to the threat of a retaliatory tax against the importer.

Retaliation for Other Countries’ Subsidies and Unfair Trade Practices:

There is little doubt that most countries use an array of subsidies and special policies to protect specific industries. These practices are based mostly on politics. The success of a trade policy based on retaliation depends on two assumptions. First, the country targeted for retaliation must be using “unfair” trade practices.

Second, the retaliation must be successful in forcing the country to change its policies. Pressure by one country on another country’s trade policy invites further retaliation. However, most leaders of developed countries should recognise the value of free trade to increase the wealth of all nations.