Read this article to learn about the Patinkin’s monetary model of quantity theory of money.

Introduction:

In 1956 there appeared a monumental work by Don Patinkin which, inter alia, demonstrated the rigid conditions required for the strict proportionality rule of the quantity theory whilst simultaneously launching a severe attack upon the Cambridge analysis.

Patinkin’s main point of contention was that the advocates of the cash balance approach had failed to understand the true nature of the quantity theory.

Their failure was revealed in the dichotomy which they maintained between the goods market and the money market. Far from integrating the two, as had been claimed, Patinkin held that the neo-classical economists had kept the two rigidly apart.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An increase in the stock of money was assumed to generate an increase in the absolute price level but to exercise no real influence upon the market for commodities. One purpose of Patinkin’s analysis was that only by exerting an influence upon the market for commodities, via the real balance effect, could the strict quantity theory be maintained.

Part of Patinkin’s attack revolved round the nature of the demand curve for money, which according to Patinkin, Cambridge School had generally assumed to be a rectangular hyperbola with constant unit elasticity of the demand for money. As a matter of fact, such a demand curve was implicit in the argument that a doubling of the money stock would induce a doubling of the price level.

Patinkin used the ‘real balance effect’ to demonstrate that the demand curve for money could not be of the shape of a rectangular hyperbola (i.e., the elasticity of demand for money cannot be assumed to be unity except in a stationary state), and moreover, such a demand curve would contradict the strict quantity theory assertion which the Cambridge quantity theorists were trying to establish Patinkin’s main point is that cash balance approach ignored the real balance effect and assumed the absence of money illusion under the assumption of ‘homogeneity postulate’ and, therefore, failed to bring about a correct relation between the theory of money and the theory of value.

The homogeneity postulate implies that the demand functions in the real sectors are assumed to be insensitive to the changes in the absolute level of money prices (i.e., with changes in the quantity of money there will be equi-proportional changes in all money prices), which indicates absence of money illusion and the real balance effect. But this is valid only in a pure barter economy, where there are no money holdings and as such the concept of absolute price level has no or little meaning. The money economy in reality, cannot be without money illusion.

Assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Patinkin has been able to show the validity and the rehabilitation of the classical quantity theory of money through Keynesian tools with the help of and on the basis of certain basic assumptions: for example, it is assumed that an initial equilibrium exists in the economy, that the system is stable, that there are no destabilizing expectations and finally there are no other factors except those which are specially assumed during the analysis. Again, consumption functions remains stable [the ratio of the flow of consumption expenditure on goods to the stock of money (income velocity) must also be stable.

Further, it is assumed that there are no distribution effects, that is, the level and composition of aggregate expenditures are not affected by the way in which the newly injected money is distributed amongst initial recipients and the reaction of creditors and debtors to a changing price level offset each other. It is also assumed that there is no money illusion. Thus, Patinkin has discussed the validity of the quantity theory only under conditions of full employment, as according to him Keynes questioned its validity even under conditions of full employment.

In Patinkin’s approach we reach the same conclusion as in the old quantity theory of money but we employ modern analytical framework of income-expenditure approach or what is called the Keynesian approach. In other words, Patinkin has rehabilitated the truth contained in the old quantity theory of money with modern Keynesian tools.

Let us be clear that Patinkin first criticised the so called classical dichotomy of money and then rehabilitated it through a different route. The classical dichotomy which treated relative prices as being determined by real demands (tastes) and real supplies (production conditions), and the money price level as depending on the quantity of money in relation to the demand for money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In such classical dichotomy there is a real theory of relative prices and a monetary theory of the level of prices, and these are treated as being separate problems, so that in analysing what determines relative prices one does not have to introduce money; whereas in analysing what determines the level of money prices, one does not have to introduce the theory of relative prices. The problem here is (before Patinkin has been) how these two theories can be reconciled—once this has been done, the other problem is— whether the reconciliation permits one to arrive at the classical proposition that an increase in the quantity of money will increase all prices in the same proportion, so that relative prices are not dependent on the quantity of money.

This particular property is described technically as neutrality of money. If money is neutral, an increase in the quantity of money will merely raise the level of money prices without changing relative prices and the rate of interest (which is a particular relative price). In Pigou’s terminology, money will be simply a ‘veil’ covering the underlying operations of the real system.

According to Patinkin this contradiction could be removed and classical theory reconstituted by making the demand and supply functions depend on real cash balances as well as relative prices. While this would eliminate the dichotomy, it would preserve the basic features of the classical monetary theory and particularly the invariance of the real equilibrium of the economy (relative prices and the rate of interest) with respect to changes in the quantity of money.

The real balance effect has been one of the most important innovations in thought concerning the quantity theory of money. This is also called ‘Pigou Effect’, because it was developed by him but Don Patinkin criticized the narrow sense in which the term real balance effect was used by Pigou and he used it in a wider sense.

Suppose a person holds certain money balances and price level falls, the result will be an increase in the real value of these balances. The person will have a larger stock of money than previously, in real terms, though not in nominal units. Similarly, if the private sector of the economy, taken as a whole, has money balances larger than its net debts, than a fall in the price level will lead to increased spending and the quantity theory of money to that extent stands modified, the important variable to watch is not M, but M/P, that is, real money balances. The real balance effect and the demand for money substitutes go to constitute important modifications of the quantity theory of money.

Thus, we find that the solution to this problem, as Patinkin develops it, is to introduce the stock of real balances held by individuals as an influence on their demand for goods. The real balance effect, therefore, is an essential element of the mechanism which works to produce equilibrium in the money market. Suppose, for example, that for some reason prices fall below their equilibrium level—this will increase the real wealth of the cash-holders—lead them to spend more money—and that in turn will drive prices back towards equilibrium.

Thus, the real balance effect is the force behind the working of the quantity theory. Similarly if there is a chance to increase in the price level, this will reduce people’s real balances and therefore lead them to rebuild their balances by spending less, this in turn will force prices back down, so that the presence of real balances as an influence on demands ensures the stability of the price level. Thus, the introduction of the real balance effect disposed of classical dichotomy, that is, it makes it impossible to talk about relative prices without introducing money; but it nevertheless preserve the classical proposition that the real equilibrium of the system will not be affected by the amount of money, all that will be affected will be the level of prices.

“Once the real and monetary data of an economy with outside money are specified”, says Patinkin, “the equilibrium value of relative prices, the rate of interest, and the absolute price level are simultaneously determined by all the markets of the economy.”

According to Patinkin, “The dynamic grouping of the absolute price level towards its equilibrium value will—through the real balance effect—react back on the commodity markets and hence the relative prices.” Hence, the integration of monetary and value theory through the explicit introduction of real balances as a determinant of the behaviour and the reconstitution of classical monetary theory, is the main theme and contribution of Patinkin’s monumentally scholarly work—Money, Interest and Prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes criticized the old quantity theory of money on two grounds: that velocity of circulation is not a constant of economic behaviour and that the theory was valid only under highly rigid assumptions. Don Patinkin agrees in his approach to the problem that the Keynesian analysis and economic variables provide more dependable interrelationships than does the velocity of circulation. In other words, a breakdown of expenditure into the sum of C and I is more useful analytical device than the breakdown into the product of the stock of money and the velocity of circulation.

Patinkin assumes full employment and deals with the above-mentioned criticism of Keynes that even under rigid assumptions the quantity theory is not valid unless certain other conditions are also fulfilled. According to Patinkin, these other conditions mentioned by Keynes (besides, full employment) are that the propensity to hoard [that part of the demand for money which depends upon the rate of interest—M2(r)] should always be zero in equilibrium and that the effective demand (AD) should increase in the same proportion as the quantity of money—this will depend on the shapes of LP, MEC, CF functions.

Don Patinkin has shown that irrespective of the values of the marginal propensities to consume and invest and the existence of a non-zero propensity to hoard; an increase in the quantity of money must ultimately bring about a proportional increase in prices (leaving the interest rate unaffected) once the real balance effects are brought into the picture. Thus, Keynes’ argument that the above conditions must be fulfilled has been proved incorrect by Patinkin.

Further, with the help of real balance effect Patinkin shows that the quantity theory will hold good even in the extreme Keynesian case where the initial increase in the quantity of money directly affects only the demand for bonds (M2) and finally Patinkin has shown that a change in the quantity of money does not ultimately affect the rate of interest—even though a change in the rate of interest does affect the amount of money demanded.

Real Balance Effect:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The term ‘real balance effect’ was coined by Patinkin to denote the influence of changes in the real stock of money on consumption expenditure, that is, a change in consumption expenditure as a result of changes in the real value of the stock of money in circulation. This influence was taken into consideration by Pigou also under what we call ‘Pigou Effect’, which Patinkin described as a bad terminological choice. Pigou effect was used in a narrow sense to denote the influence on consumption only, but the term real balance effect, has been made more meaningful and useful by including in it all likely influences of changes in the stock of real balances.

In other words it considers the behavioural effects of changes in the real stock of money. The term has been used by Patinkin in a wider sense so as to include the net wealth, effect, portfolio effect, Cambridge effect, as well as any other effect one might think of. Patinkin used the term real balance effect to include all the aspects of real balances in the first edition of his book. It is in the second edition of his book that Patinkin emphasises the net wealth aspect of real balances though he does not completely exclude other aspects as detailed above.

Unless the term is used in a wider sense so as to include all the aspects of real balances, its use is likely to be misleading and may fail to describe a generalized theory of people’s reactions to changes in the stock of real balances. The use of the term in the wider sense as enunciated above also helps us to resolve the paradox—that income is the main determinant of expenditure on the micro level and wealth is a significant determinant of income on the macro level.

The analysis of the real balance effect listed three motives why people would alter their spending and, therefore, demand for money in response to a change in the aggregate stock of money. First, the demand for money is a function of the level of wealth. The wealthier the people, the more the expenditure on goods; second, they hold money for security as a part of their diversified portfolios; third, just as the demand for every superior good increases with a rise in income, so does the demand for money. Individuals usually desire that their cash balances should bear a given relation to their yearly income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Therefore, other things being equal—wealth, portfolio structure and income determine the demand for money as also the spending decisions. Hence, corresponding to these three motives of the demand for money, there are three different aspects of the real balance effect—each of which may operate either directly on the demand for commodities or may operate indirectly by stimulating the demand for financial assets (securities etc.), raising their prices, lowering the interest rate, stimulating investments, increasing incomes, resulting in a rise in demand for commodities.

Net Wealth Effect:

Net wealth effect is the first and important aspect of the real balance effect. According to this interpretation, an increase in real balances produces an increase in spending because it changes one’s net wealth holding, which by definition includes currency, net claims of the private domestic sector on foreigners and net claims of the private sector on the government sector. Hence, consumption is a function of net wealth, rising or falling as real balances increase or decrease.

An increase in real balances results in individuals increasing their spending on goods because they are wealthier, or they have come to hold too much money in their portfolios, or because their balances have become too large in relation to their incomes.

Clearly, the direct net wealth aspect has become identified primarily with the term real balance effect. Besides, there is an indirect process also through which changes in real balances affect expenditures—an increase in real balances stimulates initially the demand for financial assets (securities), which in turn, reduces interest rates making investments more attractive, stimulating incomes and expenditures. Some writers simply emphasize the direct net wealth aspect.

They include, G. Ackley, Fellner, Mishan, Collery. These authors primarily associate the term real balance effect with the net wealth aspect, to the exclusion of all others. Other economists point out to the indirect operation of the real balance effect. Harrod and later on Mishan supported the view that there is an indirect effect of real balance phenomenon. Therefore, the real balance effect in its most general sense covers both the direct and indirect methods by which changes in real balances affect consumer spending.

Portfolio Aspect:

James Tobin is the chief exponent of this view, who is supported by Metzler. According to the portfolio aspect of the real balance effect, a decrease in price level causes investor’s portfolios to consist of more money than desired in proportion to the portfolio. Accordingly, they spend more and their effort to restore the actual to the desired amount of money changes the price level until equilibrium is restored. In their attempt to remedy the situation, individuals spend their excess supply of money directly on the physical assets or indirectly in the financial market (for securities etc.).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Equilibrium is restored when prices change (rise or fall) to such an extent that real balances once again come to bear the desired relation to the value of the portfolios. A distinguishing feature of the portfolio aspect is that people increase or decrease their expenditures in order to restore their stock of money to the optimum level with respect to their asset portfolio.

Cambridge Aspect:

This is the third aspect of the real balance effect. It differs from others in that it views the demand for money primarily as a function of income. According to Cambridge aspect, an increase in the stock of real balances increases real balances relative to income. If previously one held cash balances equal to 1/10th of the yearly income; then after an increase in real balances one would, for example, hold cash balances equal to 1/5th of the yearly income. Finding themselves with more than optimal fraction of income in money terms, people begin to spend more.

If they spend for commodities the price level increases in accordance with the direct aspect; if they spend on bonds (securities) the equilibrium will be restored through indirect process or operation. In other words, equilibrium will be restored, when other things being equal, the price level has risen in proportion to the increase in the money supply.

However, let us be clear that spending is influenced by, how wealthy people feel they are their portfolio balance and the relation of cash balances to income. The wealth effect, the portfolio effect and the Cambridge aspect of the real balance effect are all interrelated and it is merely for the sake of convenience that a division amongst the three aspects of the real balance effect is made.

Critical Evaluation:

This is Patinkin’s solution to the problem but it has not been accepted. The basic disagreements centre on whether or not it is necessary to retain this real balance effect in the real analysis. Patinkin’s model may be considered as an elegant refinement of the traditional quantity theory and its value lies in specifying precisely the necessary conditions for the strict proportionality of the quantity theory to hold and in analysing in detail the mechanism by which the change in the stock of money takes effect—the real balance effect.

Although Patinkin’s analysis is said to be the formally incomplete because it fails to provide an explanation of full long run equilibrium, yet the integration of product and monetary markets through the real balance effect represented a significant improvement over earlier treatments. For the first time, the nature of the wealth effect is made explicit. What, however, is not analysed is the manner in which the increase in monetary wealth comes about. A doubling of money balances is simply assumed and the analysis rests entirely on the resultant effects.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Patinkin effect fails to take into account the long-run equilibrium effect as has been pointed out by Archibald and Lipsey and conceded by Patinkin in the second edition of his work. They show that Patinkin’s analysis of the real balance effect is inadequate inasmuch as he confines himself to the impact effect of a change in a price and does not work the analysis through to the long-run equilibrium. The result of the debate is that the real balance effect must be considered not as a necessary part of the general equilibrium theory but as a part of the analysis of monetary stability, in that context it performs the functions of ensuring stability of the price level.

What one needs the real balance effect for is to ensure the stability of the price level; one does not need it to determine the real equilibrium of the system; so long as one confines oneself to equilibrium positions. The equilibrium obtained is no doubt a short-term equilibrium only because further changes will be induced for income recipients in future time periods. Moreover, it is very interesting to point out that if the analysis is extended to an infinite number of periods, general long-run equilibrium is found to be perfectly consistent with – a unit elastic demand curve for money—the real balance effect disappears. Therefore, this again raises a thorny question of whether the quantity theory is a theory of short-run or long-run equilibrium or indeed whether it should be considered a theory of equilibrium at all?

Even otherwise, it has been pointed out that if some kind of monetary effect has got to be present, it need not necessarily be a real balance effect as the presence of real balance effect implies that people do not suffer from money illusion—they hold money for what it will buy.

This assumption yields the classical monetary proposition that a doubling of the money supply will lead to a doubling of prices and no change in real equilibrium. But a recent article by Cliff Lloyd has shown that stability of price level can be attained without assuming simply that there is a definite quantity of money which people want to hold. The mere fact that they want to hold money and that the available quantity is fixed will ensure the stability of price level—but it will not produce the neutrality of the money of the classical theory.

Further, G.L.S. Shackle has criticised Patinkin’s analysis. He feels that Keynes analysis took account of money and uncertainties, whereas in Patinkin’ analysis the objective is to understand the functioning of money economy under perfect interest and price certainty. He accepts that once the ‘Pandora Box’ of expectations and interest and price uncertainty is opened on the world of economic analysis, anything may happen and this makes all the difference between two approaches. Patinkin’s treatment is a long-term equilibrium of pure choice, while Keynes treatment is of short-term equilibrium of impure choice.

J.G. Gurley and E.S. Shaw have also criticised the static assumptions of Patinkin and have enumerated and elucidated the conditions to show under which money will not be neutral. They bring back into the analysis, the overall liquidity of the monetary and financial structure and differing liquidity characteristics of different assets,’ which were excluded by the assumptions made in Patinkin’s analysis, in which money is not itself a government debt but is issued by the monetary authority against private debt (inside money as contrasted with the outside money).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They show that money cannot be neutral in a system containing inside and outside money. Outside money is the money which comes from outside the private sector and simply exists. One can think of outside money being gold coins in circulation or paper currency printed by the government. Outside money represents wealth to which there corresponds no debt. Inside money is the money created against private debt. It is typified by the bank deposits created by a private banking system. These writers have shown that if the money supply consists of a combination of inside and outside money, the classical neutrality of money does not hold good as claimed by Patinkin. The main difference between Keynes and Patinkin

approaches is that Keynes assumed the price level given does not assume full employment, whereas Patinkin has tried to establish the validity of the quantity theory by assuming full employment but not the price level. Patinkin discussed the validity of the quantity theory under full employment because Keynes questioned its validity even under conditions of full employment.

Patinkin’s Monetary Model and Neutrality of Money:

The mechanism of Patinkin’s monetary model can be elaborated as follows:

Suppose there are four markets in the economy—goods, labour, bonds and money. In each of these markets there is a demand function, there is a supply function and a statement of the equilibrium condition, namely, a statement that prices, wages and interest rate are such that the amount demanded in the market equals the amount supplied. By virtue of what we call ‘Walras law’, we know that if equilibrium exists in any three of these markets, it must also exist in the fourth.

Considering the markets for finished goods Keynes’ aggregate demand function would comprise of consumption plus investment plus government demand. Following Keynes, we assume that the real amount demanded of finished goods (E) varies directly with the level of national income (K), and inversely, with the rate of interest (r).

Assume further that E also depends directly on the real value of cash balances held by the community M0/P (where Mo is the amount of money in circulation assumed constant, and p is an index of the prices of finished goods). In other words, a decrease in the price level, which increases these real cash balances, is assumed to cause an increase in the aggregate amount of goods demanded and vice versa.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, the real aggregate demand function for goods is shown:

E = ƒ(Y, r, M0/P) …… (i)

Since, there exists full employment, therefore, the supply function of finished goods can be written as:

Y – Y0 …(ii)

where, Y0 is the level of real national product (equal by definition to the level of real national income) corresponding to full employment condition.

The statement of equilibrium in the goods market is then that the goods demanded equal the goods supplied that is:

E = Y …(iii)

In the labour market let us assume that the demand for labour (Nd) is equal to the supply of labour (Ns) at the real wage rate (W/p) Therefore,

Nd = g (W/p) …..(iv)

and Ns = h (W/p) …(v)

Therefore, Nd = Ns …….. (vi)

Thus, the full employment level of real national income Y0 (in the market for finished goods) is directly related to the full employment level of employment No in the labour market.

In the money market, let us assume that the individual is concerned with the real value of cash balances and that he holds or his demand for money is denoted by Md/P, and assume further as Keynes, that this total demand is divided into transactions and precautionary demand varying with the level of income (Y) and speculative demand varying inversely with the rate of interest (r). Thus,

To complete the analysis we must examine the model from the viewpoint of general equilibrium analysis. The above-mentioned nine equations and nine variables (E, Y, p, Nd, Ns w/p, Md, Ms, r) can be reduced to the following three equations and three variables p, w and r and we get the following equations for the initial period:

These are the conditions for equilibrium in the markets for goods, labour market and money market. Further, assume that there exists a price level p0, a wage level w0, and interest rate r0, whose joint existence (at p0, w0, r0), simultaneously satisfies the equilibrium conditions for all the three markets.

In other words, the same set of values—P0, w0, and r0, simultaneously cause:

(a) The formation of an aggregate function showing that the aggregate amount demanded (AD) is equal to the full employment output,

(b) Equalizes the amount demanded of labour with the supply,

(c) Equates the amount demanded for money with the supply of money. Under certain simple assumptions, the equilibrium position described here must be a stable one.

For example, suppose an excess demand for the goods raises the absolute price level and an excess demand for money raises the rate of interest and the labour market is always in equilibrium (because there is very little lag between money, wages and prices). Also assume that there are no destabilising expectations then, the above assumptions made about the forms and slopes of the various demand and supply functions ensure the stability of the system.

The Effect of an Increase in the Quantity of Money:

The equilibrium position as described above prevails during a certain initial period (t). Now, let us assume that there is a new injection of additional quantity of money into circulation which disturbs the initial equilibrium position. We shall see how a new equilibrium position is established (comparative statics) and how does the system converge to the new equilibrium position over time (dynamics).

Suppose the amount of money in circulation increases from M0 to (1 + t) M0, where t is a positive constant. It will be seen that a new equilibrium position will come to exist in which prices and wages have risen in the same proportion as the amount of money and the rate of interest has remained unchanged.

Thus, when the amount of money in circulation was M0, the equilibrium of the economy was attained by p0, w0 and r0. But when the money increases to (I + t) M0 the new equilibrium is attained at the price level (I + t) P0, wage rate (I + t) w0 and interest rate remaining unchanged at ro. Now, when the prices rise in the same proportion as the amount of money, the real value of cash balances is exactly the same as it was in the beginning or in the initial period t and the rate of interest remains unchanged.

Hence, the new aggregate demand (function) must be identical with the aggregate demand (function) of the initial period and as the market for goods was in equilibrium in the initial period it must be in equilibrium now. Similarly, if wages and prices rise in the same proportion then the real wage rate remains the same as it was in the initial period and, therefore, the labour market which was in equilibrium at the initial real wage rate (w0) must be in equilibrium now.

The position in money market is slightly different. When the amount of money supplied has increased from M0 to (I + t) M0, it is clear that the demand function (schedule) for money must also change and if the demand schedule for money does not change and remains in its original position, then it is obvious that the equilibrium cannot be attained at the initial rate of interest ro. We know that the demand schedule for money cannot remain in its original position because the nominal amount of money demanded depends upon the price level and if the price level increases, so must also the demand for money.

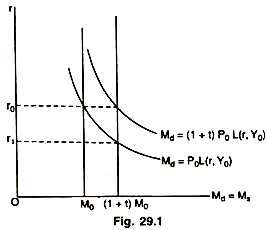

In other words, in the initial period when the price level is p0 and the rate of interest is r0, people wish to hold M0 (amount of money)—but when the price level has increased from p0 to (I + t) P0, people must wish to hold the larger amount of money; say, (I + t) M0. Hence, when the amount of money in circulation is (I + t) M0, the money market, too, is or becomes in equilibrium at the price level (I + t) p0 because the demand for money has gone up to (I + t) M0 but the rate of interest will remain unchanged at r0 as shown in the Fig. 29.1.

Patinkin has shown that the same kind of equilibrium is possible even when the analysis is dynamic, that is, through different time periods. The typical time paths of the variables would be such as to generate equilibrating forces e.g., the quantity theorists assert that in the initial stages after an increase in the amount of money the rate of interest would decline (from Or0 to Or1 in Fig. 29.1); but that when prices begin to rise due to increase in money supply, the interest rate, too, would rise again to its original level (from Or0 to Or1). In other words, with an increase in the quantity of money the price level no doubt rises continuously towards the new equilibrium level and the same will be true of the wage rates. Under these circumstances, Patinkin’s analysis has shown that the interest rate may decline first but rises once again to its original value.

Equilibrium in the market can be established only at a rate of interest lower than r0, for only by such reduction could individuals be induced to hold additional money available. But prices, on the other hand, have also changed by now. Since the excess supply in money market shows excess demand in the commodity market, this excess demand must result in raising the prices.

This, in turn, reacts back on the money market (through the multiplicative p in the demand for money equation). In particular when the price level has finally doubled, the demand for money must also double, bringing back the original rate of interest r0.

This is the crucial and central point of Patinkin’s analysis. It is true that during the process the system may, at limes, ‘over-compensate’ and the price level and the interest rate may be at some stage rise above their equilibrium values but, it cannot be denied, as claimed by Patinkin that an increase in the quantity of money would raise the price level proportionately at the invariance (un-alterability) of the rate of interest.

The whole process is bound to generate equilibrating forces which will lower the values of various variables to their equilibrium positions. Thus, we see that once we keep in mind Patinkin’s influence of the real cash balances in mind and an increase in the quantity of money will cause an equi-proportionate increase in price level and money wages while leaving the rate of interest unaffected (thereby maintaining the neutrality of money). Although we have reached this conclusion, as does Patinkin, through modern analytical framework of income-expenditure approach or the Keynesian approach but the result that emerges is that of the traditional quantity theory of money.

Neutrality of Money:

The above analysis of Patinkin’s monetary model brings to light very clearly one of the salient features of money or the quantity of money called the ‘neutrality of money’. If money is neutral, an increase in the quantity of money will merely raise the level of money prices without changing the relative prices and the interest rate. Patinkin (with the help of Keynesian framework) arrives at the classical conclusion that relative prices and the rate of interest are independent of the quantity of money.

The significance of his approach lies mainly in establishing the neutrality of money. However, it is this neutrality of money, which has been the main object of attack by Gurley and Shaw in their— ‘Money in a Theory of Finance’—the main purpose of this book is to elaborate conditions under which money cannot be neutral. Gurley and Shaw severely criticized this feature of neutrality of money, for establishing which Patinkin had taken so much pain. Gurley and Shaw distinguished between outside money and inside money to show that the money will not be neutral.

Gurley and Shaw with the help of different mathematical and monetary models show that if the money supply consists of a combination of inside and outside money, the classical neutrality of money does not hold good. A money supply consisting of a combination of inside and outside money implies that changes in the quantity of money will not simply produce a movement up or down in the general price level but will also produce changes in relative prices.

This conclusion is easy enough to understand—whenever the public holds a combination of these kinds of money, a change in the quantity of one of them without a change in the other will change the ratios in which people are obliged to hold assets and owe liabilities. If there is a change in the amount of outside money alone without a change in the amount of inside money, there must be a change in the ratios of the debt that backs the inside money to the outside money, so that a change in the quantity of money involves a change in the real variables of the economic system, as a whole.

For example, suppose there is only outside money in an economic system like gold coins and let us suppose that the quantity of this money (gold coins) is doubled which simultaneously doubles the price level, then we get back to the initial real situation—that is, all the relative prices are the same and the ratio of real balances to everything else is the same as it was before.

Let us suppose, now that there are two kinds of money gold coins and bank deposits—suppose, we double the amount of gold coins but do not change the amount of bank deposits-—then, if we double the price level we can restore the real value of gold coins, but we will reduce the real value of bank deposits and the assets backing them, so that the community cannot get back to the situation, it started from.

Consequently, there must be some change somewhere else in the economic system to reconcile people’s desires for assets and liabilities with the changed amounts that are available. This analysis takes Gurley and Shaw several hundred pages to develop, but the key to it is, the devising of a situation in which the ratios of assets change. The whole purpose of their analysis is to show that money is not neutral. H.G. Johnson also endorses these views expressed by Gurley and Shaw on the non-neutrality of money.

Lloyd Metzler has also repudiated the neutrality of money theory with the help of general equilibrium model through IS and LM curves as shown in Fig. 29.2. In this diagram, we measure income along OY and rate of interest along vertical Or. The initial equilibrium income and the rate of interest corresponding to full employment are simultaneously determined by the intersection of IS0 and LM0 curves at income Y0 and interest r0 respectively.

Now, if the central bank follows a policy of open market operations and begins purchasing securities and bonds, the nominal stock of money will increase; this, in turn, will cause a shift in the LM function from LM1 to LM2 which will determine equilibrium at a lower rate of interest r1 and the income Y1 .There is, now, an excess of income over the full employment income.

This excess of income is shown by Y0 Y1 .This represents the inflationary gap. This will initiate a process of inflation. The real balance effect will now become operative and the LM function will shift to LM1. The IS function will also shift at the same time from IS0 to IS1, on account of a reduction in consumption spending owing to a decline in the value of real balances.

The shifting of the LM curve to LM1 and IS0 curve to IS1 will restore the equilibrium again at full employment income Y0 but the rate of interest has declined from r0 to r2. Hence, the money is not neutral (because the rate of interest cannot be considered to remain unaffected).

Unless a few conditions are fulfilled the money cannot be neutral, for example, there must be an absence of money illusion, wage-price flexibility, absence of distribution effects, absence of government borrowing and open market operations and there is no combination of inside-outside money. According to Patinkin, an individual suffering from money illusion reacts to the change in money prices.

Money illusion constitutes a friction in the economic system and as such it makes it imperative for the monetary authority to create just the right amount of nominal balances if the neutrality of money is to be achieved. Similarly, flexibility of wages and prices is an important condition of the neutrality of money. Rigidity of wages and prices will prevent the real balance effect from making itself felt and hence it will become difficult to abolish inflationary pressures.

Money will, as a result, be non-neutral. The distribution effects imply the redistribution of real incomes, goods balances and bond amongst the individuals and institutions following changes in prices and stock of money. For example, a price increase may reduce the demand for consumer goods and increase the demand for money and bonds bringing about a redistribution against high consuming groups and in favour of high saving and lending groups.

Such a redistribution will mean a lowering in the rate of interest in case the quantity of money is doubled. Money, under these circumstances (unless distribution effects are absent), cannot be neutral. Again, the government borrowings and central banking open market operations have non-neutral effects on the system. Money will be non-neutral, as already seen, if there is a combination of inside-outside varieties of money.