Let us make an in-depth study of the Keynes’s General Theory in Macroeconomics:- 1. Introduction to Keynes’s General Theory 2. National Income Definition 3. Use of the Wage Unit 4. Assumptions of Keynes’s General Theory 5. Apparatus of Keynes’s General Theory 6. Simple Income Determination 7. The Two Approaches to Income Determination 8. Policy Recommendations of Keynes’s Theory 9. Limitations of the Keynesian Theory.

Introduction to Keynes’s General Theory:

Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) is surely the most influential book of recent times.

When most countries of the world were experiencing the gravest depression of the last two hundred years – that is, the so- called Great Depression of 1929-36-economists of the time faced a challenge in the problem of increasing unemployment, shrinking national income, falling prices and failing firms.

It was a man-made calamity, a situation of poverty amidst plenty. Machines, workers and raw materials were available for production but were not being used simply because the employers feared losses in the production of goods. It seemed clear that there was something seriously wrong with the capitalist way of economic organisation. Most governments were helpless spectators to the deepening economic crisis because the economic advisers would not suggest any economic measures of state intervention in the economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The conservative economists liked to wait for the free- economic system to correct its ailment itself but they could not specify for how long. It was in this type of situation that Keynes was provoked to bring out his ‘General Theory’ (So nicknamed popularly) to justify taking up some new economic measures to tackle the situation. The policy recommendations he made were not entirely new but the theoretical justification he gave for them was remarkable. He advocated the policy of starting public works and financing them with fiat money with an unbalanced budget.

Wherever these policies were adopted, recovery was remarkably rapid. Keynes’ economic thinking and economic policy at once became popular. It was a passion with the young economists and a problem with the traditional economists. The book has proved revolutionary in the sense that it has left its imprint on all branches of economic theory. We shall study, in a summary form, the main ideas of the theory.

National Income Definition:

The most important difficulty which Keynes faced in building a Theory of Employment for the economy as a whole was the definition of national income which could be related to national employment. He solved this problem in his own way.

Keynes wanted to choose the most suitable definition for this particular purpose. Dr. Marshall in his Principles of Economics had defined national income as follows: “The labour and capital of a country, acting on its natural resources, produce annually a certain net aggregate of commodities, material and immaterial, including services of all kinds… and net income due on account of foreign investments must be added in this is the true net annual income or revenue of the country, or the national dividend.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

No doubt Dr. Marshall’s definition was theoretically sound, simple and comprehensive; even then it had serious practical limitations; for example, it is not easy to make statistically correct estimates of the total production of goods and services in a country, besides the difficulties of double counting and the portion of the produce that is retained for personal consumption. A.C. Pigou has tried to limit down the concept so as to make it practicable.

According to Prof. Pigou :”…. the national dividend is that part of the objective income of the community including, of course, income derived from abroad, which can be measured in money.” According to Prof. Pigou, only those goods and services should be included (double counting being avoided) that are actually sold for money.

Pigou’s definition is precise, convenient, elastic and workable because it did away with the difficulty of measuring the national dividend inherent in Marshall’s definition. But Pigou’s definition made an artificial distinction between goods that are exchanged for money and goods that are not so exchanged. The bought and the un bought do not differ in kind from one another in any fundamental respect. Again, in Pigou’s definition, one could find the total amount of national dividend because we are to include where most of the goods and services are not exchanged for money.

In a country where most of the goods and services are not exchanged for money, i.e. they are simply bartered away; Pigou’s definition was of no use. Fisher adopted consumption instead of production as the basis of measuring the national dividend.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Prof. Fisher, “…….. the national dividend or income consists solely of services received by ultimate consumers, whether from their material or from their human environment. Thus, a piano or an overcoat made for me this year is not part of this year’s income, but an addition to capital. Only the services, rendered to use during this year by these things are income.”

Prof. Fisher’s definition was better than both Dr. Marshall’s and Prof. Pigou’s in as much as it was nearer the concept of economic welfare because welfare depends upon the goods and services made available to the individuals of the community. But it is more difficult to have an idea of net consumption than net production. Moreover, the lives of durable goods which last beyond one year are very difficult to measure. Estimates are at best estimates and they can at times differ from the actual.

None of these definitions suited Keynes as he wanted to know the factors that go to determine the level of income and employment in an economy at a particular time. He wanted to know the considerations that weigh with entrepreneurs when they decide to employ certain number of men.

However, it may be noted that the suitability of any particular definition depends upon the purpose for which it is to be used. Keynes defined income in such a manner as enabled him to determine employment in the community. It is in this respect that his definition differed from those of his predecessors. Earlier definitions did not throw any light on the factors which go to determine income or its relation with employment; this purpose was amply achieved in the definition adopted by Keynes.

Keynes’s Concept of National Income:

Keynes’ concept of national income lies somewhat between the Gross National Product and the Net National Product. Keynes does not deduct the whole of depreciation from the Gross National Product, he subtracts a little less than the whole amount of depreciation called ‘User Cost’.

It is the cost of using capital equipment rather than of leaving it idle. User Cost is the difference between the depreciation in the value of the machine when it is put to use and the depreciation which would occur if not in use plus the expenditure incurred on its maintenance and upkeep. For example, a machine worth Rs. 1,000 in the beginning of the year remains worth Rs. 750 at the end of the year having suffered a reduction in the value worth Rs. 250 as a result of depreciation.

Even if the machine were not put to use, it would have suffered a loss of value on account of say rusting etc. But in this case the value of the machine has been maintained at Rs. 900 at the end of the year by incurring a small maintenance cost of Rs. 10. Thus, the user cost would be Rs. 250 (Rs. 100 + Rs. 10) = Rs. 140. In this way by adding the user costs of all the firms in the whole economy, we get the aggregate user cost of the whole economy.

When we deduct the aggregate user cost from the Gross National Product, we shall get national income of the economy in the Keynesian sense represented by A-U (where A is the Gross National Product, being the total product or value of goods and services obtained in a year and U represents the total user cost). According to Keynes, number of people to be employed (N) depends upon income (7) in this sense.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes, however, felt that the concept of income in terms of A-U is of little use when the community has to decide how much to spend on consumption. Here, the idea of ‘net Income’ assumes special significance. Net income is found by deducting supplementary costs V from the income (A-U). Thus, net income = A – U – V. In other words, both user costs (U) and supplementary costs (V) have to be subtracted from Gross National Product (A) to obtain the net national income.

Supplementary costs are those costs which cannot be foreseen or are beyond the control of entrepreneurs, i.e. these are contingent costs like plant becoming obsolete, catching fire. etc. Even if the entrepreneurs wished he could not avoid this loss. Such costs have to be deducted from gross income to get net income on which the consumption of the community depends. Since consumption depends upon net income, it is necessary that net income be calculated as accurately as possible.

To conclude, Keynes uses the term income in two senses:

(1) Gross Income (A-U) on which the volume of employment depends

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(2) net Income (A-U-V) on which Consumption of the community depends.

Use of the Wage Unit:

Besides the concept of income, another concept which continued to bother Keynes was the choice of units for the purpose of macroeconomic analysis and measurement in the absence of which he could never go along conveniently.

It is very necessary to measure the aggregative quantities like saving, investment, consumption, income output etc. In fact, monetary unit (money) had been employed usually as the standard of measurement. Keynes himself measured these quantities in terms of money but found it rather unsatisfactory because with changes in prices, money does not depict true changes in the economic aggregate. Keynes, therefore, adopted a new unit for measuring the changes in the national output, that is, the unit of the employment of labour.

All industries employ labour and their outputs can be expressed in terms of employment that they offer. Keynes expressed employment in terms of labour units. A labour unit may be taken to mean one hour of work by ordinary, unskilled or common worker. Thus, if volume of employment (labour units) in the economy is increasing, it is clear that there is an increase in the national output. Further, the amount of wages received by ordinary labour for an hour’s work, Keynes called-wage unit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

More efficient and skilled labour, he observed, can be evaluated at a higher rate and the wage unit in this case can also be higher. In this way, Keynes reduced the magnitude of employment to wage units and measured the various types of aggregative magnitudes in terms of wage units. Most of the analysis of the General Theory is conducted in terms of relatively stable wage units (though the analysis of the theory of prices and inflation is not done in terms of constant wage units because with the rise in price, wages alone cannot remain constant).

Assumptions of Keynes’s General Theory:

To simplify his theory considerably, Keynes employed a few assumptions which must be noted to avoid any confusion or misunderstanding.

These assumptions are:

1. The Short Period:

Keynes was writing about the short-period problem of depression. Therefore, he made the specific assumption of short-period so as to concentrate on the problem at hand. Keynes assumed that the techniques of production and the amount of fixed capital used remain constant in the model of his theory. In his view, short period is that in which new investments do not change the technique, the organisation and equipment. This considerably simplified his analysis, for he could thereby take employment and output as moving together in the same direction.

2. Perfect Competition:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He assumed that there is a fairly high degree of competition in the markets. Or if there is some monopoly clement somewhere, then its degree remains unchanged.

3. Operation of the Law of Diminishing Returns:

Further, directly flowing from his assumption of unchanging techniques was his assumption of the operation of diminishing returns to productive resources or increasing cost.

4. Absence of Governmental Part in Economic Activity:

The government is assumed to play no (significant) part either as a taxer or as a spender. He ignored the fiscal operations of the government in his analysis to highlight the causes of and remedies for the instability of the pure capitalist economy.

5. A Closed Economy:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes further assumed that the economy under analysis is a closed one; that is, he did not explicitly recognise in his analysis the influence of exports and imports. This considerably simplified his work.

6. Heroic Aggregation:

Keynes in his general theory dealt with aggregates like the national income, saving, investment, etc. and measured them in wage units to be able to ignore the questions arising out of changes in relative prices of resources.

7. Static Analysis:

The ‘General Theory’ does not trace out the effect of the future on the present economic events clearly. Its analysis remains comparatively static, though at times Keynes introduced expectations in his analysis.

Apparatus of Keynes’s General Theory:

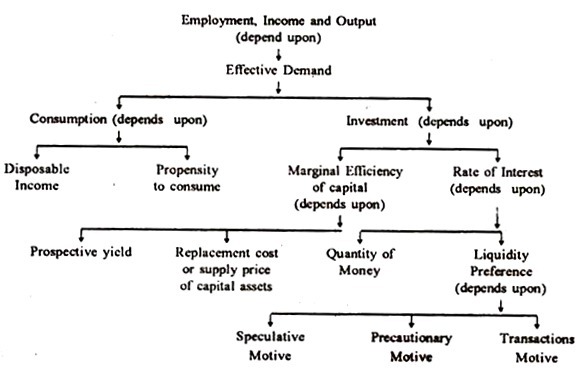

His theory is built up on the basic idea that ‘Effective Demand’ determines employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The effective demand in turn depends upon:

(1) Consumption, and

(2) Investment, which depends upon marginal efficiency of capital and the rate of interest.

Consumption C and Investment I further depend on a large number of other influences in the economy. Some of these are controllable by policy, others are not so. We have to select the more easily manageable factors influencing aggregate income and employment. All this requires detailed study of Keynes’s General Theory. Before we do so, it will help us to know the general framework or apparatus of Keynes’s theory.

The general apparatus of the Keynesian theory of employment can be briefly summarised in the following form:

Keynes’s first proposition was that total income depends upon the volume of total employment, which depends upon effective demand (D), which in turn, depends upon consumption expenditure (D1) and investment expenditure (D2): therefore, Effective Demand D = D1 + D2. Consumption depends upon the size of income and the propensity to consume while investment depends upon marginal efficiency of capital and the rate of interest.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The rate of interest depends upon the quantity of money and liquidity preference while the marginal efficiency of capital depends upon the expected profitability (M.E.C.) and replacement cost of capital assets. These propositions contain the essentials of the general theory’ of employment. Let us study the concepts and relations one by one.

1. Effective Demand:

Effective demand manifests itself in the spending of income. It is judged from the total expenditure in the economy. The demand in the economy is ordinarily for two types of goods – consumption goods and investment goods. The demand for consumption goods forms a major part of the total demand and it goes on increasing with increase in income and employment. At various levels of income and employment, there will be different levels of aggregate demand, but all the levels of demand are not effective.

Effective demand is the demand for goods and services in the economy as a whole which is fully satisfied by the supply of the output as a whole. It was this theory of demand and supply of output as a whole which was neglected for more than 100 years and which Keynes analysed. He divided effective demand into two components – consumption and investment. Consumption depends upon propensity to consume and investment is determined by inducement to invest.

2. Propensity to Consume:

Propensity to consume, also called the consumption function, is a key concept to Keynesian theory of employment. The equation Y= C+I, expresses the relationship between C and Y. We can write this relation as C=f(Y). It tells us that there is a direct relation between income and consumption. Consumption function is written as a schedule of various amounts of consumption expenditure that consumers will incur at different levels of income.

It simply lays down that as our incomes increase; consumption will also increase though not in the same proportion as the increase in income. Propensity to consume refers to the actual consumption that takes place at different levels of income. An important fact about the consumption function is that it is stable in the short run because the consumption habits of the community remain more or less stable in the short run. According to Prof. Hansen, Consumption Function is the most important contribution of J.M. Keynes.

3. Saving (S):

In Keynesian Economics saving is defined as the excess of income over consumption, i.e., S = Y – C. The fundamental fact about saving is that its volume depends upon income. A man’s saving is that part of his money income that is not spent on consumption goods. Generally speaking, saving is done in the form of cash or in buying shares and stocks, bonds etc. Community saving is simply an aggregate of individual saving. Classical economists believed that saving was a great private and social virtue.

Keynes, however, called it a social vice, as more saving on the part of an individual will mean less saving on the part of another individual, leaving the total savings of the community unaffected. Thus, according to Keynes, during a period of depression or recession encourage spending more to increase effective demand.

4. Investment (I):

In Keynesian economics, investment does not mean financial investment i.e., investing money in buying existing stocks and shares, bonds or equities. Here, it means real investment in new capital goods Investment in Keynesian economics is that expenditure which should result in an increase of employment of the factors of production in new factories and consumption.

In practical life the exact line of demarcation between investment and consumption is easily drawn; for example, expenditures on food and clothing are clearly consumption while those on buildings, factories and transportation facilities are easily investment.

Investment also includes additions to stocks of manufactured and semi-manufactured goods (inventories) as well as in fixed capital. Production in excess of what is currently-consumed is called investment. The distinction between consumption and investment is fundamental to Keynes’ General Theory.

Since consumption expenditures in the short run remain stable, Keynes’s theory stated in simple terms maintains that employment depends upon investment. This may be great simplification of facts but it brings forth the crucial importance of investment in Keynesian theory of employment. The fact of the matter is that employment fluctuates on account of the fluctuations in investment. Therefore, it is important to understand what determines the amount of investment.

5. Marginal Efficiency of Capital (MEC):

Investment depends upon the marginal efficiency of capital on the one hand and the rate of interest on the other. Marginal efficiency of capital refers to the expected profitability of an additional capital asset; it may be defined as the highest rate of return over cost accruing from an additional unit of a capital asset. In other words, it is the highest rate of return over cost expected from producing one more unit (marginal unit) of a particular type of capital asset.

In Keynes’s view, fluctuations in the marginal efficiency of capital are the fundamental cause of the business cycle. Its importance lies in the fact that in a private enterprise economy investment depends upon it. If the expected rate of profitability (MEC) of an additional unit of capital asset is high, private investors would be prepared to invest, otherwise not. There are a large number of short-run and long-run influences which affect the marginal efficiency of capital.

6. Liquidity Preference (LP):

Liquidity preference is a new concept used by Keynes. His theory of interest depends upon it. Interest, in turn, affects investment and employment. Liquidity preference means preference for liquidity or cash. Keynes’s view was that money offers ready purchasing power for commodities and bonds. To guard against the risks of uncertain and vague future, people want to hold some of their assets in cash. In order to carry daily transactions, to meet unforeseen contingencies and in order to take advantage of the market movements of bond prices, people want to hold cash; this constitutes the demand side of the Keynesian theory of the rate of interest.

The desire to hold cash, however, is not an absolute desire; it can be easily overcome by offering sufficiently high reward in the form of interest. The higher the liquidity preference i.e., the desire of the people to hold cash, the higher the rate of interest which must be offered to overcome their liquidity preference. Keynes considered government as the sole supplier of money in the short period.

7. Multiplier (K):

Multiplier is the key concept of Keynes. Keynes’ multiplier is investment multiplier in the sense that a small increase in investment (A1) is expected to lead to a much higher increase in income (Ay). Investment multiplier (Income multiplier) expresses the relationship between an initial investment and the ultimate increase in national income.

It shows that an initial increase in investment increases the national income by a multiple of it. Keynes believed that whenever an investment is made in an economy, the national income increases not only by the amount of investment, but by something much more than the original investment.

Suppose in order to cure unemployment an investment of Rs. 5 crores is made in public works, the effect of this original investment would be to increase the national income several fold. If the national income is increased by an amount of say Rs. 15 crores then investment multiplier is 15/5 = 3. In the analysis of trade cycle, theory of multiplier is an important tool Keynes’s policy of public works was based on his belief in the working of the multiplier vigorously in the depression phase.

8. Underemployment Equilibrium:

The concept of underemployment equilibrium is the most revolutionary idea put forth by Keynes. Classical economists always believed that the economy was in equilibrium at full employment level only, but in his general theory Keynes could show successfully that the free enterprise market economy could be in equilibrium at less than full employment-to this, he gave the name of underemployment equilibrium.

According to Keynes, this was the normal situation of a free-enterprise market economy and economists hailed this idea of Keynes as the most significant gift to economics. Keynes disputed the classical assumption of automaticity of full employment and the classical prescription that in the event of an economic depression wage cuts would bring about full employment in the economy.

According to him what actually existed in the capitalist society was under-employment and not full employment. Underemployment equilibrium was the result of private under-investment in relation to the savings available in the capitalist economy at the given income level.

Simple Income Determination:

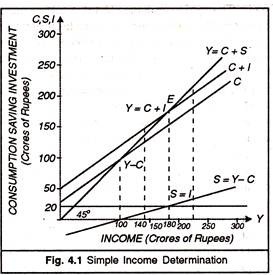

Having discussed the factors which determine the level of economic activity (income, output and employment) in the economy, Keynes went on to build a simple model of income determination at a particular time. He did not draw any diagram in his ‘General Theory’ but his ideas can be better understood with the help of such a simple diagram as is given below. It shows the simple process of income determination in an economy.

The horizontal axis of Figure 4.1 shows the levels of income and the vertical axis shows the levels of consumption, saving and investment in the economy. The straight line through the origin (Y = C + S) makes an angle of 45′ with the two axes. Therefore, the various points on this line are equidistant from the horizontal and the vertical axis.

The points on this line fulfill the equilibrium condition in the economy: i.e. at different points on this line total income is equal to total expenditure. The equilibrium level of income in the economy can be determined only with reference to a point on this line. It may be called ‘Income = Expenditure’ line.

The straight line labelled C shows the behaviour of consumption expenditure with respect to income. It is straight line rising upwards to the right intersecting the 45° line where the whole of income is spent on consumption. It has a constant slope and therefore shows a functional relation between income and consumption.

As such it is called Consumption Function. Let us presume (with Keynes) that the level of investment is not related to income. Let investment be 20 crores of rupees whatever the level of income. We can add it to the various levels of consumption shown by the consumption function and get the C +I (total expenditure) line. The C +I line lies parallel to and above C, the vertical distance between them showing investment For determining the equilibrium level of income we need the total expenditure (C + 7) line and the 45° line (Y= C+S).

The point £ where the aggregate expenditure line intersects the 45° line shows that income is equal to total expenditure, Y= C + I. In other words, it shows that whatever people earn is being spent either on consumption or on investment. Therefore, point E shows equilibrium in the economy. The equilibrium level of income is determined at Rs. 180 crores.

The Two Approaches to Income Determination:

In his ‘General Theory’ Keynes used two approaches to the determination of income:

(1) The Income-Expenditure Approach and

(2) The Saving Investment Approach.

Both these approaches lead to the determination of the same level of income. It will be useful for us to understand the two approaches at the outset.

1. The Income-Expenditure Approach (Y = C + 1):

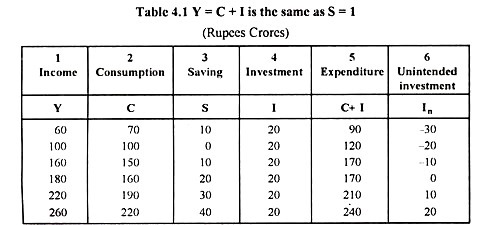

Keynes defined the equilibrium of the economy as that situation in which total income (Y) equals the total expenditure (C + I). This is to say that total expenditure constitutes aggregate demand while total income is the aggregate supply. Table 4.1 is meant to illustrate the income expenditure approach to macro equilibrium. Column 1 in the table shows the various levels of income while column 2 shows the levels of consumption associated with it.

As income increases, consumption also increases but not so much as the increase in income. The result is that saving, which is income not spent on consumption, goes on increasing. Column 3 in the table shows that at the level of income of 50 crores, saving is negative, that is, minus 10 crores. This is because people spend on consumption to the extent of Rs. 70 crores while their income is only Rs. 60 crores.

It means disserving or accumulated-wealth consumption. At the income level of Rs. 100 crores consumption is also Rs. 100 crores and this means zero saving. Further as income rises, saving also rises. Consumption is only one, though major, component of expenditure. The other component is investment.

2. The Saving-Investment Approaches (S=I):

The second approach to income determination given in the ‘General Theory’ is based on the Keynesian definitions of Saving and Investment. Keynes defined saving as that part of income which is not spent on consumption, S = Y – C. He defined investment as expenditure on goods and services not meant for consumption, i.e., I = Y = C. When equilibrium prevails in the economy, income equals expenditure and since S and I are both equal to Y- C, saving must equal investment.

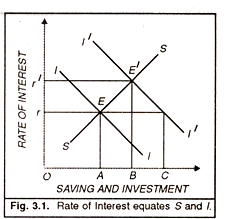

Saving in that case equals intended or planned investment. In ease of disequilibrium, planned or intended or ex-ante saving is more than or less than planned investment. In Table 3.1, planned saving at the levels of income of Rs. 180 crores equals planned investment. At income levels less than this, planned saving is much less than planned investment. As there is disequilibrium, income will have to rise. At levels of income greater than Rs. 180 crores, planned saving is more than planned investment so that income falls to correct the disequilibrium. When the economy is having an equilibrium level of income, saving and investment are equal. Not only is income equal to expenditure, Y = C +I, but saving also equals investment, S = I.

The values of income, consumption and saving shown in Table 3.1 have been plotted in Figure 3.1. We find that the S and I curves intersect vertically down the point E at which C + I line intersects the 45° line. The same level of income gets determined whether we have the Y = C +I approach or the S=I approach.

Since the former is a direct approach while the latter is an indirect approach, the two approaches are called the Front- Door Approach and the Back-Door Approach respectively. This dual approach to income determination has proved of great help in theoretical model building on the one side and national income accounting on the other.

Policy Recommendations of Keynes’s Theory:

There were a few direct policy implications of Keynes’ theory.

Firstly, it was clear that a laissez-faire capitalist economy will not be able to maintain full employment even if it is attained. Therefore, Keynes justified state intervention in economic affairs to fight instability.

Secondly, he could very nicely provide reasons for departures from the policy of balanced budgets. During depression he would advocate a deficit budget to stimulate effective demand and in times of inflation, he wanted the government to have a surplus budget to restrict effective demand. Professor A.P. Lerner, a disciple of Keynes, called it the policy of Functional Finance.

Thirdly, Keynes spelt out the specific form which state intervention has to take to counter economic depression. He laid down the policy of starting public works financed from deficit financing through direct throw of additional currency or via credit creation. Such public investment, he said, best achieves the multiplier effects.

He observed that public works need to be undertaken only as long as private investment is deficient. As soon as private investment is stimulated and the economy is well on its way to recovery, public works need no more be carried on. Thus, through his theoretical contribution Keynes not only shook the Classical Theory in its roots but also demolished its policy implications completely. He gave practically useful policy.

Limitations of the Keynesian Theory:

The limitations of Keynes’s theory and policy became obvious when the policies advocated by the Keynesians were implemented after the Second World War. Keynesian demand management policies were used by the governments of most Western countries in the attempt to keep the unemployment levels down.

Generally these policies were successful in preventing heavy unemployment like that experienced during the days of the Great Depression. But unfortunately they tended to give rise to the phenomenon known as ‘stop-go’. That means, Keynesians wanted the government to go on raising aggregate demand to reduce unemployment to the acceptable level.

But it was found that Keynes’s policies tended to create inflationary pressures to control which the government had to reduce aggregate spending. Thus all ‘go’ periods tended to be followed by ‘stop’ periods and it became difficult to achieve long-term economic growth. The main problem with the Keynesian model was that it was meant for the short run. It is not always possible to predict the effects of policy changes adopted in the short run.

Secondly, the Keynesian model failed to adequately take into account the problem of stagnation with inflation. Indeed, the basic model assumed that wages and prices are fixed as long as the government is reducing unemployment. Prices in Keynes’s model use only after full employment. Experience in the 1970’s in particular has shown that high rates of inflation can co-exist with high rates of unemployment. This is known as stagflation. No explanation of this is provided by the Keynesian Theory.

Thirdly, the coincidence of inflation and unemployment makes the Keynesian policy recommendation very questionable. For example, if the economy is in a deflationary gap situation but is also suffering from a 15 per cent rate of inflation, an increase in government spending or a cut in taxation designed to reduce the unemployment is likely to worsen the rate of inflation.

Fourthly, Keynesian model has been criticised on the ground that it tends to understate the influence of money on the real variables (like consumption and investment) in the economy. In the Keynesian model, a change in money supply only affects national income through its effect on the rate of interest. It is because of this that Keynesians have put more faith in fiscal rather than monetary policy.

We conclude by observing that the nature of economic problems of more developed economies has changed so much that Keynesian policies alone are not so much relevant. These policies needed modification and moderation. Nevertheless, the way in which modern economists view macro-economic problems owes much to the Keynesian framework. Keynes’s work has left a deep mark on modern macro-economics.