In this essay we will discuss about the foreign trade in India during different periods. After reading this essay you will learn about: 1. Foreign Trade during 1757-1857 2. Foreign Trade, 1857-1914 3. Foreign Trade, 1914-19 4. Foreign Trade, the Inter-War Period 5. India’s Foreign Trade during the Second World War 6. Foreign Trade 1951-1966.

List of Essays on Foreign Trade in India, during different Periods

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Foreign Trade during 1757-1857

- Essay on Foreign Trade, 1857-1914

- Essay on Foreign Trade, 1914-19

- Essay on Foreign Trade, the Inter-War Period

- Essay on India’s Foreign Trade during the Second World War

- Essay on Foreign Trade 1951-1966

1. Essay on Foreign Trade during 1757-1857:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The archaeological excavations carried out during 1920-1930 at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa and recent excavations at Rangpur in Gujarat indicate that well before 1500 B.C., Indians were carrying on trade with far off lands in West Asia and beyond.

The skill of the Indians in the production of delicate woven fabrics, in the mixing of colours, the working of metals and precious stones, and in all manner of technical arts enjoyed a world-wide celebrity. Indian manufactures, therefore, were very much in demand all over the world.

So it was till after the coming of the Europeans to India in recent centuries. In-fact, most of the explorations in the 15th and 16th centuries were inspired by a keen desire to acquire direct control of the profitable trade with India which was then controlled by the Arabs.

The discovery of America was only incidental and in the earlier years, the hero of Europe was not Columbus, the discoverer of America, but Vasco de Gama who discovered the direct sea-route to India via the Cape of Good Hope. Fabulous profits were earned by the Dutch, the Portuguese, and the British in their early trade with India.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Textiles formed the chief articles of export which found a ready market in the whole world including England. Between 1658-1664, 15000 pieces of calicoes were annually exported from Hoogly to England and the average rose to 91,000 pieces between 1673-78.

In the year 1700, England imported 0.95 million pieces of calicoes and 0.11 million pieces of Bengal silks. Indigo, cotton yarn, opium, Lac, Marble, precious stones, iron and steel, and Rice were the other articles exported from India.

The imports into India mainly consisted of articles of Luxury meant for the rich. To this may be added gold and silver and horses from Iraq and Arabia. Accounting to Moreland, “the masses of Indian consumers were too poor to buy imported goods.” However, the masses everywhere and always are too poor to buy imported articles of luxury.

The character of the import-trade is better explained by the self-sufficient character of the Indian economy. Machines had not yet been invented and Indian craftsmen were unbeaten in their arts. Regarding the balance of trade, the demand for our manufactures was keen in the world markets while our demand for the manufactures of other countries was so small as to be negligible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Indian produce was exported in Indian ships, manned by Indian sailors. Naturally, not only the balance of trade but the balance of payment also was heavily in India’s favour.

In other words, India was a creditor country and she received the excess of her exports over imports in silver and gold. Total exports of bullion to India during this period through the East India Company alone were worth £ 21 million. In this connection, Pliny, the Roman Historian, lamented that a river of gold was flowing for the Roman Empire to India.

The British Economic Historian, L.C.A. Knowles found that “the whole difficulty of trading with the East Lay in the fact that Europe had so little to send out that the East wanted— Therefore it was mainly silver that was taken out.”

The later part of the 18th century saw territory after territory in India coming under British control. The same period offered England the great boons of Industrial Revolution. New methods of manufacture and enormous development in transport, mining and banking stimulated British productive powers with great speed.

This combination of technical superiority in production and political control over India, helped by a deliberately perused colonial policy, reverted India from an enterprising commercial nation to a docile country meekly supplying raw materials to her rulers and readily purchasing articles which she herself could have manufactured.

While India thus deteriorated, England progressed from an agricultural state to industrial and commercial preemince. These two trends, rapid but opposite, were not entirely unconnected. In-fact, India’s deterioration was mainly due to British control and British prosperity became possible because of her extensive Indian possessions.

As Palme Dutt points out, the result of this policy was that, between 1815-1832, “the value of goods exported from India fell from Rs. 1.30 crores to below Rs. 10 lakh —a decline of 12/13 of the trade while the value of the English goods imported into India rose by sixteen times from 2.6 lakhs to Rs. 40 lakhs. By 1850, India, which had for centuries, exported cotton goods to the world, was importing 1/4 of all British exports —the same process could be traced in respect of silk goods, woolen goods, iron, pottery, glass and paper.”

An important feature of the trade during this period was the great increase in the private trade of the company’s servants. The rise of this ‘privilege trade’ strengthened the position of the free merchants and, in response to their persistent demand, the East India Company’s monopoly of trade with India was abolished in 1813.

This, according to Hamilton marks “a new era in the history of India’s foreign trade.” From now onwards, the company confined itself to old branches of commerce while the private traders put the trade of India on a broader footing and started new exports.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

From the year 1833, the company ceased to be a trader; the China trade was also thrown open and ordinary traders could henceforth carry on trade between India and the Far East. This tended to further stimulate Indian trade.

Value of Trade:

Compared with modern standards, the value of trade was not large. It was just Rs. 2.5 crores in 1813 and even so late as 1834, directly after the close of the company’s operations, it amounted to no more than Rs. 14.3 crores. In 1857, it stood at Rs. 54.2 crores. The expansion of trade was comparatively slow on account of the natural difficulties which remained after the company had established its rule over much of India.

During the first half of the 19th century, roads were non-existent except where they had been constructed for military purposes. “Off these great routes, all traffic was carried over narrow unmetalled tracks impassable during the monsoons.”

Moreover, the freight charge from Calcutta, Madras or Bombay to London by way of Good Hope was high and the duration of the voyage long so that taking into account the charges for internal transit, the existence of trade was almost impossible except for articles for which India possessed a more or less monopoly and which could stand a long journey.

Composition:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The most outstanding feature was the change in the composition of the foreign trade. At the beginning of the 19th century, India’s chief exports were such articles as indigo, salt-petre and manufactures of fine quality and workmanship such as cotton and silk piece goods. But soon India entered on her career as an exporter of raw-materials and food-stuffs.

Her main exports comprised raw- cotton, raw silk and silk goods, raw wool, grains, sugar, opium, indigo and jute. Imports also underwent a similar change and consisted of cotton, silk and woolen goods, machinery and metal manufactures —articles which she had previously exported.

Direction:

Even though Indian foreign trade was thrown open to free commercial enterprise in 1813 and gradually, all the European nations were placed on a footing of equality, yet the U.K. retained a monopoly of all the European trade with India. This was due to her political domination of India and also because England had become the great carrier of the world.

Indian trade with ‘foreign Europe’ was carried in British ships from and to England; foreign goods for India being sent from the continent to England for reshipment and Indian goods for the continent being sent to England for distribution.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

R.C. Dutt has calculated that somewhat over half the entire trade of India was with Great Britain. The rest was carried on with China, Sri Lanka, Persia and other Asiatic regions, excepting a small trade of brief duration with the U.S. in die import of apples stored in ice —the first crude beginning of the frozen fruit trade.

Balance of Trade:

Another striking fact about the foreign trade during this period was the great disproportion between the imports and exports. Except for the year 1856-57, when India had an adverse balance of trade caused largely by the Indian Mutiny, exports always exceeded imports. The balance was favourable only to the tune of Rs. 2 crores in 1834-35 but the export surplus increased to Rs. 5.5 crores in 1855.

Other countries gave India a fair return for what they received. Only Great Britain extracted a tribute for which she made no commercial return. For her, India’s foreign trade was, in a way, an important instrument for exploiting Indian economy and for providing the sinews for her own industrial expansion.

V.V. Bhatt rightly says, “if this amount (exacted from India) had been invested in India for development, she would have been able to attain a growth rate only a little lower than that attained by the U.S. and the U.K. during the 16th Century.”

2. Essay on Foreign Trade, 1857-1914:

The period 1857-1914 marks the evolution of the modern period in the history of India’s foreign trade. The most striking feature of this period was the steady growth, both in the volume and value of trade —the value having increased from Rs. 69.6 crores in 1859-60 to Rs. 440.3 crores in 1913-14, an increase of over six times in a span of less than sixty years.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The expansion of trade, though continuous, was not uniform. There was a sudden jump during 1864-66 which was caused by the extra-ordinary circumstances created by the American Civil War when the exports of raw-cotton greatly increased.

Between 1873 and the end of the century, trade development was comparatively slow on account of frequent famines and recurring scarcities which ravaged different parts of India. Violent fluctuations in the exchange value of the rupee further aggravated the situation.

However, the first fourteen years of the 20th century saw a more rapid expansion when the value of foreign trade more than doubled from Rs. 213.27 crores in 1900 to Rs. 440.31 crores in 1913-14. This expansion was brought about by several factors.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had already reduced the distance between England and India by about 3000 miles and gave new trade opportunities to countries facing the Mediterranean. This, together with improvement in naval architecture and the rapid growth of mercantile marine, gave a great boost to India’s trade with distant lands, specially in bulk goods.

At the same time, improved means of communications and transport opened up the country far and wide making it possible to distribute imported articles in the countryside and also to carry Indian produce to the port towns for export to various parts of the world. Also, various internal custom barriers and transit duties, which had previously restricted trade, were swept away by 1853.

At the same time, the principle of Free Trade was now vigorously applied to India as well. As a consequence, all export duties were abolished by 1874 and import duties, with a few minor exceptions, were removed in 1882, thereby removing the major hurdle in the way of trade expansion.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Above all, the establishment of peace and order under the British brought about a great expansion of normal economic activity including foreign trade of the country. Many British Indian authorities like John Strachey have cited trade expansion as a visible proof of increasing prosperity of the country—a conclusion not warranted by facts.

Far from bringing about prosperity, India’s foreign trade strengthened the forces maintaining stagnation and, therefore, did not have expansionary effects on the economy. India could derive no benefit because her foreign trade was carried on by foreign merchants with foreign capital and in foreign ships.

What is more, India’s trade was not natural and free but was artificially stimulated and, therefore, forced, unhealthy, and economically unsound. As R.C. Dutt points out, “the large imports of cotton goods into India were secured by restrictions on the Indian industry while large exports of food grains were compelled by a heavy Land Tax and a heavy tribute.”

Therefore, the argument that the growing volume of trade was an index of increasing prosperity is both misleading and fallacious. This maybe seen from the fact that in 1900-1901, a year of famine and distress, the value of trade was greater as compared with that in 1881-82, a year of relative peace and prosperity.

Composition:

The dynamics of foreign trade of a country is normally moulded by and is an index of the progress of her internal economy. In the case of India, however, this relationship was reversed. As Ganguli explains, from 1860 onwards, the internal economy of the country came to be ‘activated and moulded into shape by the dynamics of her foreign trade.’

This, in fact, was a natural consequence of the stage of economic development through which India was passing at that time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

With the decline of the indigenous industries, the country was obliged to import various consumer goods. There was also the import of capital for construction of the railways, irrigation works, and private investments in Plantations, commerce and industrial enterprises like jute manufacture.

Over the above, the government had also to pay the ‘Home-charges’ to England. It was, therefore, necessary to create surplus in agricultural produce which was the only source available for earning foreign exchange. That explains why exports mostly consisted of agricultural commodities like raw material and food stuffs while imports consisted of a large variety of manufactured articles of daily use.

Among imports, cotton textiles, which once formed the bulk of India’s exports, now accounted for the largest share of imports, their value having risen from Rs. 9.6 crores in 1859-60 to about Rs. 49 crores for the quinquennium 1909-10 to 1913-14.

This sharp increase in the import of Lancashire goods meant the displacement of the native weaver from his traditional employment and his decline to the position of a casual labourer.

The development and expansion of the modern Indian shipping and weaving industry brought about a change only in the nature and type of cotton manufactures exported from Lancashire, the only difference being the substitution of inferior by superior varieties.

These imports were, therefore, not an index of growing purchasing power in the country but a source of national loss, a portent of the country’s economic and industrial death. To that extent, they were “not a blessing but a curse.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

What was more unfortunate, a large proportion of these imports was made either to satisfy the daily wants of the foreigners residing in India or for meeting the needs of the government. The proportion of imports consumed by the large mass of the people was extremely small, probably ‘represented by a few pence per head.”

Exports showed a general up-trend although there were yearly fluctuations, depending upon the state of foreign demand for the Indian agricultural produce and climatic condition in the country.

In the case of raw-cotton exports, there was a spectacular increase during 1864-66 due to abnormal demand from Lancashire, but with the resumption of American supplies to England after the end of the civil war, these exports fell off to a low level. Exports of raw-cotton recovered again, despite the rapid expansion of Indian industry, owing to the discovery of new markets on the continent and Japan.

The exports of raw-jute began on a large scale after the Crimean war which cut off Dundee’s supply of Russian flax and hemp. Exports of indigo suffered a severe decline and ceased to be an important commodity of export in the 20th century. So was the case of opium after 1880.

Of greater interest was the export of food-grains which rose from Rs. 3.6 crores to Rs. 22.2 crores during the period. The total quantity of food grains exported from the country increased from a little under 0.65 million tons in 1867-68 to an annual average of 4.4. million tons in the quinquennium 1909-10 to 1913-14.

A revealing aspect of the food grain trade was the high level of exports maintained even during the famine years. In a way, the increase in food- grain export was beneficial to the country because it helped India to earn sufficient annual exchange balance with which to pay ‘Home charges’. However, its effects on internal supplies and prices were highly detrimental to the poorer sections of the population.

The changes in the export trade had a powerful impact on the choice of crops by the cultivator. Under the stimulus of expanding demand, wheat cultivation on irrigated lands in the Punjab, Sind, and North Western Provinces, jute cultivation in Bengal and that of oil seeds in Madras was further extended.

The fall in the demand for indigo led to its displacement by other commercial crops. A side effect of this kind of specialisation was that some areas like Berar developed a permanent deficit in food grains which had to be imported against the sale of cotton and other commercial crops.

To sum up, India, by the end of this period had become an exporter of food-stuffs, raw materials, and Plantation products, while she depended upon imports for a large part of her clothing and a variety of miscellaneous manufactures. And this transformation from an industrial to an agricultural country was the result of a deliberately designed policy.

There was, however, one heartening trend in that Iron and Steel, machinery, and milk-work started entering the country’s imports while cotton and jute textiles, now as products of modern machines, began once again to find their way into export trade.

Direction of Trade:

The bulk of India’s foreign trade consisted of exports to or imports from England, the share of other countries being of “little significance.” The U.K.’s share in India’s total foreign trade amounted to 62% in 1875-76 and although it continuously declined thereafter, yet it was a substantial 41% in 1913-14.

Taking imports and exports separately, we find that in 1875-76, no less than 83% of the total imports came from the U.K. though the proportion declined to 64.2% in 1913-14. In exports, the share of the U.K. fell from a little more than 48% in 1875-76 to 23.5% in 1913-14. The countries to gain were Germany, the U.S. and particularly Japan. In the pre-war period, trade with central Europe also increased by leaps and bounds.

These changes not withstanding, the U.K. still stood first among countries supplying goods to India. She also look more Indian exports than any other single country. The next most important countries were the U.S. and Japan while the imports from Java and the exports to Germany were not inconsiderable.

Balance of Trade:

A feature of India’s trade during this period was that the increase in exports was more marked than the increase in imports and that, with expanding trade, the gap between exports and imports also kept widening. It was only Rs. 20 crores in 1865 but rose to Rs. 57 crores by 1913-14.

Far from being an addition to national wealth, this excess of exports represented the annual ‘tribute’ paid by India to England. As bullion was not available, this unilateral transfer of funds, called the ‘Home charges’ had to take the form of goods. Hence, a favourable balance had to be maintained. This gave a compulsory character to a large portion of our exports.

The significance of this export surplus lies not so much in ‘the drain of wealth to England’ as Dudabhai contended, nor in the adverse terms of trade on which India made this unilateral transfer of funds —a view held by Ganguli.

A far more serious consequence was that the country produced “even at the cost of food for her people, those crops for which there was foreign demand and parted with food grains in which, taking good years with bad, the country hardly had any surplus. Famines and scarcities in India, during this period, were, therefore, not wholly unconnected with the character and composition of the country’s foreign trade.”

3. Essay on Foreign Trade, 1914-19:

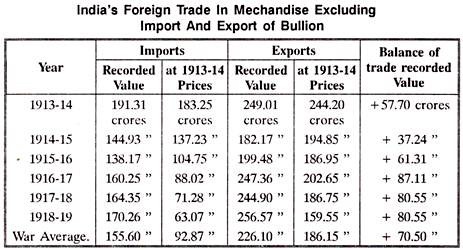

The First World War dealt a severe blow to India’s foreign trade. Calculated at 1913-14 prices, its overall average value was reduced to 60% by 1918. Although both exports and imports were adversely affected, but the decline in imports was continuous and far more serious. Exports suffered in the early years of the war but recovered in 1916-17 only to decline again in the last two years of the war.

This is evident from the fact that the value of imports, calculated at 1913-14 prices, declined from Rs. 183.25 crores in 1913-14 to Rs. 63 crores in 1918-19 while exports came down from Rs. 244.20 crores to Rs. 159.55 crores in the same period.

Indeed, the war had offered a great opportunity for industrial and trade expansion, but on account of several reasons, India could not make full use of it.

Firstly, the war led to a complete stoppage of trade with the enemy countries like Germany while trade with the Allied countries like Great Britain, France, and Belgium could not be maintained at the pre-war level due to their pre-occupation with the war.

Trade, even with neutral countries, was subjected to several restrictions so as to prevent ‘leakage’ of munitions and food-stuffs to Germany and make Indian supplies available exclusively to Allies.

In 1913-14, 10% of our exports went to Germany and 3.5% to Austria-Hungary. Taken together, these two countries were important purchasers of our raw-produce, particularly food- grains, raw-cotton, raw-jute, seeds, hides and skins.

The closing of their markets to our produce combined with curtailment of exports to France and Belgium, brought about a fall in the value of cotton, jute and oil-seeds which meant severe losses for the growers of these products.

A more disturbing factor was the sharp rise in freights as a result of the disappearance of enemy ships from the high seas, the pressure of war requirements on what was available, and hostile interference with trade routes to neutral countries.

Freights, at the close of 1916-17 rose to 14 times their pre-war level.’ This factor largely took away the advantage which India might otherwise have derived from the great demand in Europe for her commodities.

Thirdly, the destruction of wealth, the devastation of regions, and the trend towards armament production, which the war implied, reduced the European purchasing power.

Fourthly, the financial difficulties of the European countries, and the restrictive measures adopted by them further reduced the scope of Indian commerce.

Fifthly, India’s industries, which depended upon foreign supplies of machinery, suffered when their imports were curtailed. Their export capacity was thus restricted.

Sixthly, on account of England’s pre-occupation with the war, a fear was entertained that Japan and America might capture the Indian market. Accordingly, heavy duties were levied on imports whose volume was reduced. Export duties, levied for purposes of revenue also had a similar effect.

Seventhly, the physical distance between India, Europe and U.S.A. proved another handicap. Had India been nearer, perhaps trade could have continued between them at the same level. However, the distance factor, coupled with the danger of submarines and mines on the way, severely restricted India’s trade with these countries.

Eighthly, as the duration of the war was uncertain, every country desired to be self-sufficient and, therefore, encouraged her manufacturing industries.

Lastly, India’s trade was also adversely affected by foreign exchange dislocations.

A noteworthy point, however, is that every country did not suffer likewise. Rather, some countries like Canada, Brazil, and Argentina speeded up their industrialisation and became India’s rivals in several important markets. In-fact, the war served as a kind of a universal protective tariff of which U.S.A., Japan, Australia, South Africa, and other countries made the best use and rapidly expanded their economies.

However, in the words of Narayanaswami Naidu, “the lack of fiscal freedom and national planning prevented India from securing the maximum benefits out of the world war.”

Composition:

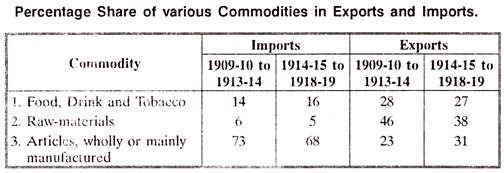

During the war, our chief exports were cotton, jute, oil seeds, hides and skins, jute and cotton manufactures, food grains, tea, tobacco and ammunition while imports comprised cotton, raw twist Yarn and piece goods, sugar, petroleum, chemicals and drugs, silk, raw and manufactured Iron and steel, machinery, railway plant and hardware.

Group wise, the % age share of manufactured articles in our imports declined from 73% before the war to 68% during the war while their share in exports increased from 23% to 31%. The share of raw-materials fell from 46% to 38% of exports.

Economists like Anstey and Pillai have held the slight change in trade composition as an incontestable evidence of “a remarkable development in industrial activities.” Such a view, however, has been refuted by the Indian Fiscal Commission (1921-22) which found that industrial development during the war was “on a limited scale” and that, in comparison with other countries, it was slow.

In this connection, it is also worth remembering that the industries, which showed the maximum activity during the war, were all connected with the supply of war —materials.

Evidently, in these industries, the same rate of progress could not be maintained once the war demand was over and the belligerent countries returned to peace-time economic activity. For example, commodities whose exports received a special boost were hides and skins, oils, raw rubber, jute bags and jute cloth and ammunition.

As regards ammunition, India could not take much advantage of the situation on account of her dependence on imports for most of the capital equipment and technical experts. Jute bags were needed for trench warfare and hides for the manufacture of boots for the soldiers. The war-time expansion of the exports of these commodities was, therefore, a temporary phase and it was bound to fall off once the war was over.

Besides, the exports of these articles were specially stimulated to meet the war requirements of the Allies. Therefore, the slight increase in the percentage share of manufactured articles in total exports shows, if at all, only that the existing factories were overworked and not any large-scale industrialisation of the country. By and large, the country stood where it was before the war.

One important feature of the war-time export trade was the decline in wheat exports from 1308 thousand tons in 1912-13 to 73 thousand tons in 1918-19. The chief reasons were the increase in internal demand owing to a rise in the standard of living and the prohibition and regulation of exports during the war.

Direction of Trade:

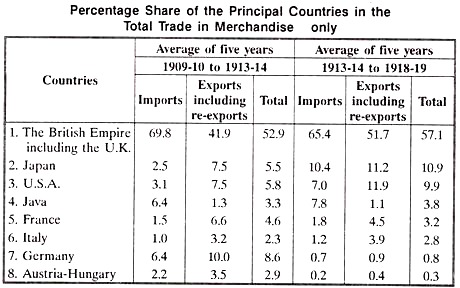

As a result of artificial channelization of Indian trade, the share of the British Empire increased from 53% in the pre-war period to 57% during the war.

Though the share of the U.K. in our imports slightly declined on account of her preoccupation with the war effort, she still retained her position as our principal supplier —supplying as much as 56.5% of our imports. Her share of our exports however, increased from 25.1% to 31% during the same period.

The next two countries in the matter of trade relations were the U.S. and Japan. These two countries had kept out of the turmoil during the initial years of the war and they quickly filled up the gap created by the elimination of the central European powers and England in our import trade. The inroads of Japan were especially marked in textiles while the U.S.A. made headway in the metallurgical trades.

As a result, the share of Japan in our total trade rose from 5.5% before to 11% during the war while that of U.S.A. increased from 6% to 10%. On the other hand, the share of continental Europe and Germany, which accounted for 11.5% of our total trade before the war, was eliminated and this hit Indian agriculture hard.

These countries were important purchasers of our raw produce, particularly food-grains, raw-cotton, raw jute, oil seeds and hides and skins. The closing of these markets combined with the curtailment of exports to France and Belgium brought about a fall in the prices of cotton, jute, oil-seeds etc. which inflicted severe losses on the producers of these products.

Balance of Trade:

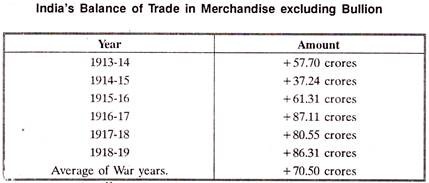

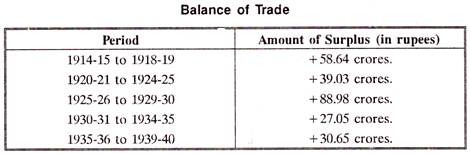

As u result of persistent demand on the part of the Allies for goods of national importance and with the cutting off of imports of piece-goods, sugar, salt, kerosene, and a ‘hundred and one articles’ of necessity, the gap between exports and imports, or the so-called favourable balance of trade increased.

Exports of merchandise exceeded imports, on an average, by 51% during the pre-war years whereas during the war, they exceeded, on an average, by only 52%. Thus, the favourable turn in the balance was only marginal except for the years 1916-18 when the export surplus was substantial.

Findlay Shirras points to this trade surplus as an evidence of the prosperity of the country during the war years. This so-called prosperity was only superficial in as much as this surplus was earned at great cost to the people. Drastic curtailment of imports reduced the supply of many necessities of life while larger exports drained away a large part of what was produced within the country.

The people were, therefore, starved of various daily needs in order to earn this favourable balance. Dr. Parimal Ray has rightly questioned the prosperity of citing the favourable balance to prove the supposed prosperity.

According to him, “the retrograde tendency of our trade during the war period is true beyond any shadow of doubt and no amount of sophisticated argument or statistical jugglery can disprove or conceal it.” This favourable balance of trade had one important consequence, namely, the break down of the Gold Exchange Standard.

4. Essay on Foreign Trade, the Inter-War Period:

The end of the war saw a gradual removal of many war-time restrictions on exports as well as resumption of normal trade relations with the enemy countries. The shipping situation also eased and there was brisk demand for Indian goods in western countries.

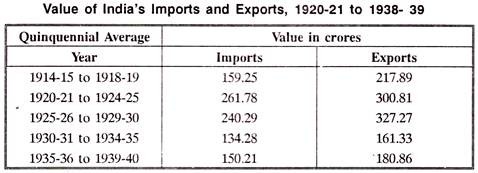

This led to a boom in India’s foreign trade, its value rising from Rs. 377.15 crores for the quinquennium, 1914-16-1918-19 to Rs. 536.68 crores in 1919-20 and Rs. 595 crores in 1920-1921.

This, however, proved to be a temporary phase and soon the tide turned. Prices began to fall, exchange tended downwards, exports fell and a slump intervened. Many Indian importers refused to take delivery of goods previously ordered, repudiated their liabilities, and dis-honoured their drafts.

There was a gradual recovery after 1922-23, especially on the export side, on account of the progressive stabilisation of the European currencies, a general improvement in their credit position, and the apparent settlement of the Raparations question.

The exports, both in value and volume, reached their peak in 1924-25 when the harvests were plentiful and the export prices high. Thereafter, the value of our exports began to fall due to a decline in world prices of agricultural commodities.

The Wall Street Collapse in October, 1929, which culminated in the Great Depression dealt a severe blow to India’s trade. Exports and imports both declined; the quantum index of exports fell from 108 in 1929-30 to 75 in 1932-33 while that of imports declined from 103 to 83 during the same period.

The greater fall in exports was due to the fact that the prices of agricultural commodities and raw-materials, which formed the bulk of India’s exports, fell to a much greater extent than the prices of manufactured goods which she mainly imported.

Imports also declined on account of the reduced purchasing power of the consumers, the tense political situation in the country and the expansion of home production, especially cotton textiles and sugar.

Imports fell from Rs. 240 crores in the quinquennium 1925-26 to 1929-30 to Rs. 134 crores in 1930-31 to 1934-35 whereas exports declined from Rs. 327 crores to Rs. 161 crores in the same period. The slump in the export trade was at its worst in 1931-32 when the visible balance of trade in merchandise was reduced to about 3 crores of rupees, the smallest figure on record till then.

The worst phase of the Depression came to an end in 1932 and the early months of 1933 saw a considerable revival of business activity in several countries. By 1936, the world had emerged from the perils of stagnation.

The devaluation of the gold currencies, the Restriction Schemes adopted by the producers of primary commodities, and the rearmament programmes created favourable conditions for an all-around rise in prices.

By 1936-37, there was an appreciable advance in the prices of India’s agricultural products; her export trade, in consequence, made considerable recovery and the surplus balance in merchandise rose to Rs. 78 crores.

The process of recovery had not gone far when the business ‘recession’ delivered yet another blow. The prices of most Indian stable products declined sharply thereby reducing the income of the agriculturist.

The situation was worsened by the Sino-Japanese conflict which curtailed the trading capacity of Japan, India’s principal customer for cotton. On top of it came the separation of Burma in 1937 which particularly affected Indian exports. The combined result of all these factors was a fall in the value of India’s trade.

The inter-war period was, undoubtedly, one of great stress and strain. Other countries, however, protected themselves by adopting suitable commercial and currency policies. India’s political status as an appendage of England eliminated the possibility of such a course.

Her policies were so fashioned as to protect the ‘mother’ country’s interests first. As a consequence, her share in world exports declined from 3.7 in 1928 to 2.9 in 1938.

Composition of Trade:

According to Ganguli, “Experience shows that when countries in a relatively early stage of economic development make industrial progress, imports of raw- materials and partly manufactured goods increase while exports of crude materials and food stuffs decrease in relative importance.”

At the same time, there is a decrease in the relative significance of manufactured imports and an increase in the relative importance of manufactured exports. When industrial development is stimulated by tariff protection, such a shift in the composition of the import trade becomes more pronounced. These tendencies were broadly reflected in the composition of the inter-war trade.

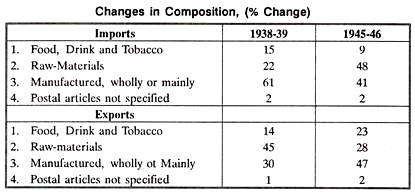

The overall share of consumer goods in our imports declined from 54% in 1925-26 to 33% in 1938-39 but that of raw-materials increased from 15.6% to 28.4% while that of capital goods from 23.2% to 26%.

The pronounced increase in the imports of raw-materials can be explained only in terms of industrial development which took place in India during the period of the depression as a result of protection afforded by a high revenue tariff in general and tariff protection to selected industries in particular.

As a result of this development, manufactures somewhat declined in our imports but India was still dependent for her supplies of textiles, machinery, Iron and Steel goods, chemicals, and other industrial necessaries, petrol and sugar.

As regards exports, broadly somewhat less than half consisted of raw-materials and the rest belonged in about equal portions to the food and the manufactures group. There were, however, appreciable annual changes in the shares of three groups of exports. For example, in the food group, the range of fluctuations was between 20-28% and the main items responsible for the variations were food-grains, pulses, and Hour.

In the raw-materials group, raw-cotton was the largest item and this fluctuated widely though raw-jute and seeds also underwent considerable changes. The large changes in the manufactures group arose mainly from the share of cotton and jute, India’s two most important exports in the category of manufactures. Leather and dressed hides and skins were two other important items.

Exports of raw and manufactured silks, cotton twist and yarn, and Indigo, however, suffered a decline owing to the intensity of foreign competition, the rise of substitutes and the defective quality of Indian goods.

India’s raw-materials had no difficulty in gaining popularity abroad, but increase in their exports was deterimental to Indian cotton, Iron and steel, and also Chemical and Leather industries which had to depend solely upon the internal supply of raw-materials.

Direction of Trade:

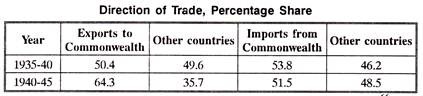

The inter-war period saw a steady change in the direction of trade also. The Commonwealth’s share in imports fell from nearly 2/3 to 54% while that of other countries rose from 35% in the period 1920-25 to 46% during 1935-40.

Among other countries, Japan steadily increased its share even during the depression. Germany made an equal gain while U.S.A., which had earlier increased its share from 5.7% to 9.3% (1923-33), later suffered a decline. Java lost heavily in sugar.

These directional changes were brought about by two factors:

(a) The United Kingdom was often at a comparative disadvantage in meeting India’s increasing demand far raw-materials and capital goods. This led to a diversion of imports from the U.K. to other countries.

(b) The effect of the second factor was conditioned by the regional distribution of India’s trade balances. Before the Depression, India was able to meet its fixed obligations to England out of its trade surplus with Europe, the Far East and America. This was no longer possible with the general restrictive trade policies of the 1930’s.

As soon as the multilateral trading system disintegrated, many countries were unable to pay for their large import surpluses from India. They therefore, tried either to increase their sales to India or turned to other alternative sources of supply in countries which were anxious to buy their goods. India was, therefore, unable to pay for her imports from the U.K. which declined very heavily in consequence.

Unlike imports, exports during the inter-war years went increasingly to the Commonwealth countries and within the Commonwealth to the U.K. Even before the Depression, exports had tended to concentrate on the Commonwealth.

Imperial Preference further strengthened this tendency. As a consequence, the share of the Commonwealth countries in India’s exports went up from 39% during 1920-25 to 50% during 1935-40 whereas the share of other countries came down from 61% to 50%.

Balance of Trade:

The inter-war period also saw significant changes in India’s balance of trade on account of considerable fluctuations in export receipts. Exports attained high levels in the middle twenties, their value being Rs. 400 crores in 1924-25. But during 1930-31 — 1932-33, the quantum index of exports heavily declined so that their value came down to Rs. 132 crores in 1932-33.

The recovery to Rs. 202 crores in 1936-37 was followed by a further heavy decline due to the recession and the separation of Burma. The size of the export surplus, therefore, kept varying but broadly from 1928-29 onwards, it started declining till it touched the rock bottom of a bare Rs. 3 crores in 1932-33 and Rs. 5 crores in 1935-36.

While India continued to have an overall favourable balance, its regional distribution underwent a great-change. In the post-war years, India’s adverse balance with the U.K. greatly increased from an average of Rs. 14.4 crores for the war years to Rs. 40.9 crores in 1928-29. On the other hand, her favourable balance with countries other than U.K. increased.

The Depression, however, brought about a sea-change. Our regional balance with the continental countries declined from an average of Rs. 39.40 crores for the ten years ending 1927-29 to Rs. 3.21 crores for the ten years ending 1937-1939. This was a matter of great significance to India because she was a debtor country with huge foreign obligations to discharge.

India could not repudiate these obligations for they were the symbol of her slavery to England. They had to be met and so our exports had to exceed imports. India adopted the only course open to her, namely, the large scale exports of distress gold in order to fulfill her obligations. According to B. R. Shenoy, during the seven years preceding April, 1938, India exported gold to the tune of Rs. 314.62 crores.

5. Essay on India’s Foreign Trade during the Second World War:

With the outbreak of the war in September, 1939 and its extension in scope and intensity, a number of factors affecting the volume, value, composition and direction of India’s foreign trade were brought into play.

Volume:

The immediate effect of the war was to bring about a decline in the volume of the trade. On account of the preoccupation of the exporting countries with the war effort, restriction of shipping space, increasing incidence of freight and war —risk insurance, and the cutting—off of the large supplies of imported goods from some of the enemy countries, the machinery of import controls, the volume of imports was reduced to the minimum.

The quantum of exports also declined due to the loss of the continental markets and an acute shortage of shipping space which hampered exports even to the U.K. Later, the loss of Burma and the Far Eastern markets and the imposition of export restrictions in India accounted for the decline.

On the whole, the quantum of exports in 1944-45 stood at 53% of that in 1938-39 while the quantum of imports was reduced to only 40% in 1943-44 but improved to 71% in 1944-45 due to very heavy imports in that year.

It is worth while nothing that during the whole period of the war, excepting 1944-45, the quantum of imports fell much more rapidly that the quantum of exports. It, in effect, meant that India was forced to maintain the war effort at the cost of great suffering to the Indian people.

Value:

The decline in the volume of India’s foreign trade was more than compensated by the rise in its value. The total value of merchandise trade rose from Rs. 385 crores to Rs. 459 crores. On the whole, the recorded value of imports and exports in 1944-45 showed an increase of 34% and 35% respectively over that of 1938 -39. This increase, in the face of a decline in quantum, was brought about by a steep rise in prices both of imports and exports.

Composition:

No less significant were the changes involved in the composition of trade. On the export side, the proportion of manufactured articles rose but that of raw-materials declined. On the other hand, the proportion of raw-materials in our imports increased while that of manufactured articles declined.

Manufactures improved their position in exports from 30% to 47% while raw-materials declined from 45% to 28%. The trend was reversed in the case of imports where the share of manufactures declined from 61% to 41% but raw-materials improved position from 22% to 48% in 1945-46.

Commodity wise, exports of tea and jute manufactures continued to increase throughout the period. Exports of raw jute and oil seeds, which were showing increase in the pre-war period, declined substantially due to the German occupation of the central European countries where India had a good market in these commodities. Exports of short staple cotton fell sharply because of stoppage of supplies to Japan.

The War, however, gave a great boost to the export of cotton cloth and Yarn on account of the withdrawal of British and Japanese supplies from Middle East countries and Africa. Exports of Indian piece goods doubled between 1938-39 and 1939-40 and quadrupled by 1941-42 when India emerged as one of the leading exporters of cotton cloth and Yarn in the world.

As a result of protection, there was a consistent decline in the imports of cotton yarn and manufactures, sugar, cement, matches and other consumer goods. On the other hand, imports of oil, especially mineral oil, chemicals, dyes and colour, long staple cotton continued to increase throughout the war period.

Prof. L.C. Jain has interpreted these trends as an indication of the extent of industrialisation during the war. This interpretation, however, is unwarranted. The increase in the percentage share of raw materials was caused by the large increase in the imports of Petroleum not for industrial requirements but for war- purposes.

Similarly, most of the increased exports of manufactures consisted of cotton and Jute goods—; products of old and well established industries. Therefore, as Dr. Lokanathan points out, “There is not much point in assuming that war-time industrialization in these goods had established the basis for permanent expansion.”

Direction:

The war as well brought about a change in the direction of trade. Several countries fell, one after another, under German occupation and were thus lost as markets to India.

Added to this was the acute shipping shortage and the insecurity of many of the sea-lanes which brought about a relative decline in long distance traffic and a corresponding improvement in our trade relation with nearby countries like Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kenya, Australia and Sri Lanka etc.

Their share in our import trade improved from 12.5% in 1938-39 to 45% in 1944-45 and in our exports, from 8% to 20%. The share of the U.S. also increased from 8.4% to 21.2% in exports and from 6.4% to 25.7% in imports.

Although England’s share both in our exports and imports declined, yet the overall share of the British Empire remained unaltered by the war-time trade and exchange restrictions. India’s exports to this area increased from 50.4% in 1935-40 to 64.3% in 1940-45 but its share in our imports fell from 53.8% to 51.5% during the same period.

A significant development during the war was that the terms of trade after an initial improvement in 1939-40, showed a continuous deterioration in the next three years on account of the greater rise in the prices of imports. It was only during the last two years of the war, when the prices of exports rose higher and faster, that the terms moved in India’s favour.

Balance of Trade:

India’s balance of trade was traditionally favourable. War only made it more so. England, engaged as it was in a life and death struggle with Germany, was no more in a position to meet India’s needs. And so were the Allied countries. Their exports to India declined.

On the other hand, the Allied powers needed almost everything that India could produce and export to help their war effort. Surplus, therefore, in our trade balance began to grow so much so that at the end of the war, India had not only liquidated her external debt amounting of £ 320 million but also accumulated a large sterling balance worth Rs. 1733 crores by April, 1946.

Be it noted that this surplus in trade was earned at a huge cost in terms of human privation and suffering. The heavy cut down of imports led to acute shortages of several essential goods. On the other hand, expanding exports, pushed sky high by government efforts, drained away most of whatever was available for civilian consumption in the country. Prices sky-rocked causing untold hardship and misery to the people.

In one respect, however, the emergence of a huge sterling balance signified one important effect. The pressure of unilateral transfer of funds on our export trade, which had been causing anxiety as a dislocating factor in the economic situation during the inter-war period, entirely disappeared. This was certainly conducive to better economic readjustment, particularly in periods of economic distress.

No account of India’s foreign trade would be complete without making a mention of new features it acquired during the war. One was that trade on govt. account assumed great proportions.

It included:

(1) Supply of goods to British forces stationed in India and the purchases made by the Govt. of India as agents of the British Govt. and

(2) Imports from the U.S.A. under the Lend-Lease scheme and exports from India under the Reverse Lend-Lease.

These transactions were excluded from the published custom’s returns.

The second was the institution of elaborate trade controls. Exports restrictions were devised with a view to preventing supplies of certain exports reaching the enemy by indirect channels and also to conserve the supplies of a number of essential articles either for internal consumption or for the use of the Allied countries.

Export controls comprised prohibition of all exports to enemy countries; prohibition of certain exports to non-enemy countries; permission for the export of certain articles to non-enemy countries only under licence and lastly, permission for the export of certain articles without licence, or under open general licence only to specified countries.

An important development in the application of export control was the institution of a scheme for the control of foreign exchange proceeds of exports to the hard currency countries. Unlike the export-control, import control in India was instituted several months after the out-break of the war when imports of certain commodities were licensed to conserve foreign exchange.

The main purpose of import control was to conserve available supplies of foreign exchange, and to ensure the economic use of shipping space and the optimum utilisation of the productive capacity of friendly nations for essential war purposes. These trade controls not merely continued with modifications after the war but entrenched themselves in the govt’s thinking as an instrument of peace-time trade policy.

6. Essay on Foreign Trade 1951-1966:

The launching of the First Five Year Plan brought, in its wake, important changes both in India’s foreign trade and trade policy which, from now onwards, was designed to promote industrialisation in particular and economic development in general.

Foreign trade was no longer a conduit pipe for ciphoning of surplus from India to Britain; rather, it served as a pipeline for the inflow of capital resources from abroad and reflected the impact of development plans on the economic structure of the country. That is why it shows important changes in regard to its volume, value, composition direction and balance.

The first significant change was with regard to the volume of trade. The quantum index of imports rose from 100 in 1950-51 to 202 in 1965-66 while that of exports increased from 100 to 118 during the same period. This increase in the volume of trade was a reflection of the tempo of economic and industrial development in the country.

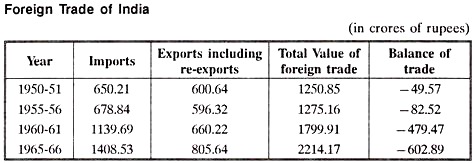

Apart from volume the value of trade also increased. In 1950-51, India’s total visible trade amounted to Rs. 1251 crores, but it rose to Rs. 2214.17 crores in 1965-66 —an increase of about 77%. This increase, though impressive in absolute terms, was, relatively speaking, insignificant. In 1951, India’s share in the world trade came to 2.2% but it declined to a mere 0.8% in 1966.

Even non-communist developing countries showed much better performance. Seen from yet another angle, the expansion in India’ trade was disappointing. In 1951-52, imports, expressed as a percent of Gross National product, stood at 13.7 but declined to 9.2 in 1965-66 while exports fell from 11 to 5.3% during the same period. This means that even the Gross National Product grew at a faster rate than trade.

Composition of Foreign Trade:

As was to be expected, the plans led to the stepping up of the total foreign trade of the country, imports increasing substantially but both imports and exports undergoing important changes in composition.

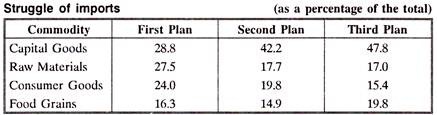

As can be seen from the table above, the import pattern during the first fifteen years of planed development changed rapidly in favour of capital goods. The share of raw-materials and consumer goods, on the other hand, declined. This changing pattern was an index of the growing industrialisation of the country.

The share of capital goods increased from 28.8% in the First Plan to 47.8% in the Third Plan while the share of consumer goods declined from 24% to 15.4% due to the tightening up of import licensing and increased production of these goods within the country.

The decline in the import of raw-materials was largely accounted for by the decline in the import of raw-jute and, to some extent, also of raw cotton where the country made determined efforts to increase production in order to rid itself of dependence on Pakistan.

This may be seen from the fact that imports of raw jute as a percentage of total agricultural imports, fell from 12.9% in 1951-52 to 1.2% in 1965-66 while those of raw-cotton came down, during the same period, from 26.3% to 9.6%. The only disquieting feature of our import trade was the continuance of food-grain import which was the consequence of the failure of agricultural production to keep pace with growing demand.

However, the imports of agricultural machinery and fertilizers increased by nearly 100% between 1956-57 to 1960-61 and by 171% between 1961-62 to 1965-66. Industrial imports included substantial quantities of petroleum products, non-Ferrous metals and intermediate products. Imports of complete machinery were increasingly replaced by spare parts and components reflecting the drive towards import substitution.

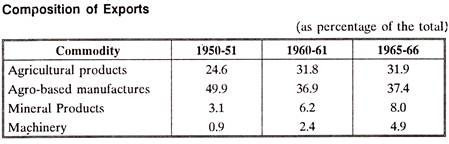

A significant aspect of the export trade was that sixteen commodities grouped in four categories accounted for 78.5% of the exports in 1950-51 and 82.2% in 1965-66. This suggests a high degree of concentration which, inter-alia, implies that decline in the demand for even a few commodities could seriously upset the balance.

Another note worthy feature was that the proportion of agricultural products and agro-based manufactures such as jute manufactures, cotton manufactures, leather goods and coir products, remained fluctuating around 70%; in 1950-51, the proportion was a little higher at 74.5% whereas in 1965-66, it was a little less at 69.3%. It does not, however, imply that the inter commodity variation in exports was negligible.

This is evident from the fact that coffee and oil-cakes did not enter the exports trade in 1950-51 in any substantial quantity but in 1965-66, they had become important articles of export. Similarly, tea, cotton and jute manufactures, which constituted 60% of the exports of India between 1948-50, declined to 44% in the Third Plan.

Likewise, the exports of Oil seeds and oil-nuts disappeared altogether. These changes notwithstanding, the relative position of the groups remained unchanged.

Yet another new feature of exports-composition was the emergence, for the first time during this period, of several new articles of export such as oil-cakes, fruits and vegetables, Iron and steel, handicrafts, and engineering goods.

Exports of fish preparations constituted only 1.9% of India’s exports in 1950-51 but 4.2% in 1965-66. The share of fruits and vegetables rose from 0.2% to 1.6%. Other manufactured goods including clothing, footwear and scientific instrument rose from 0.8% in 1950-51 to 2.7% in 1965-66.

Another group of exports consisting of Iron ore, manganese ore and Mica recorded substantial increase, their % age share rising from 4.1% in 1951-52 to 8% in 1965-66. Fluctuations in the volume of annual exports of these commodities were mainly caused by the irregular demand for manganese ore whereas the exports of Iron ore grew rapidly due to heavy demand in all countries.

The most welcome development, however, was the emergence of engineering exports. This group included metal manufactures, electrical and other machinery items, transport equipment and other engineering goods.

In fine, the structure of India’s exports, as at the end of Third Plan, did not reveal any fundamental change although there were, apart from the emergence of new exports, considerable inter-commodity variations.

Direction of Trade:

During the fifteen years of planned development, significant changes took place in the direction of trade as well. Some traditional markets declined in importance while some new ones emerged prominently. On the export side, share of the U.K. fell sharply from 26.8% in 1951-52 to 18.1% in 1965-66 while that of Australia declined from 6.6% to 1.8%.

The other side of the trade diversification was represented by the rise in the share of Japan from 2.2% to 7.2% during the same period. The U.S.S.R. emerged as the third Largest purchaser of Indian goods, her share being 1% in 1951-52 and 11.6% in 1965-66. Exports to the U.S.A. declined only marginally but to the East European countries as a group rose from 1.2% to 19.5% of the total.

These important changes apart, one unsatisfactory feature of the directional pattern was that India’s trade relations with the neighbouring countries of South East Asia, the Middle East, East Africa and other developing countries continued to be weak and neglected. Exports to the E.C.A.F.E. countries declined from 24.6% in 1951-52 to 19.8% in 1965-66 but those to Africa increased, though marginally.

There was similar change in the direction of imports as well. U.K.’s share fell from 18.5% in 1951-52 to 10.7% in 1965-66. There was a decline in the share of Middle Eastern Countries and Africa also while that of U.S.A. and East European countries went up to 37.7% and 11.3% respectively.

Apart from increase in India’s production, both industrial and agricultural, and the need to find markets for the exports and better and cheaper sources of supply for her urgent developmental requirements, large scale tying of aid with the purchase from the aid-giving country played a major role in changing the direction of India’s trade.

Exports to the East European countries, for instance, increased rapidly under the stimulus provided by the rupee-payment arrangements on a bilateral basis.

Balance of Trade:

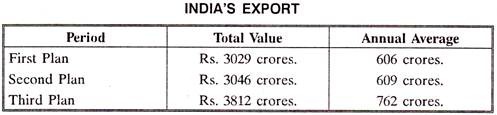

As can be seen from the table given above, India’s exports were near stagnant during the period of the first two plans, but rose by 25% in the Third. In-fact, during the first two plans, not much was expected from trade as an instrument of economic growth nor were efforts made in that direction excepting on an adhoc basis.

The First Plan significantly stated that “in period of relatively easy foreign exchange supplies, the need for export promotion will be less evident” while the Second Plan only hoped that “increased production at home will be reflected in larger export earnings.”

There was little appreciation of the co-relation which foreign trade has with other vital sectors as shipping facilities, financing and other servicing institutions nor was any thought applied to the important role which sales personnel and selling organisations play in developing exports.

In short, between 1951-61, India neglected the question of balance of trade and the Government policy hardly suggested using trade as an important weapon to fight the worsening foreign exchange situation at home. It was during the Third Plan that exports were given high priority and measures initiated to expand them.

The overall achievement, however, was meagre as can be seen from the fact that India’s share in world exports declined from 1.4% in 1955 to 0.8% in 1966. Several reasons have been advanced to explain India’s poor performance on the export front.

According to Mr. J. Patel, the main reason for the stagnation of India’s exports was that she had been trying to “sell more of the wrong things to the wrong places.” In other words, the trouble was that India had been only trying to sell more of the same things to the same people who no longer wanted more of them.

India kept on concentrating on sealing more quantities of her traditional items like tea, jute, manufactures and cotton textiles in her traditional markets but did not reorganize her economy so as to take advantage of those sectors of the world trade which were developing faster.

Automobiles, televisions, cameras, tape recorders and other consumer durables which could have been sold in advanced countries, India either did not produce or else, in terns of price and quality, her products could not compete with similar products from advanced countries.

What was true of consumer durables was equally true of capital equipment and chemicals. India could have pushed her exports to the developing countries in the immediate post-war period but the opportunity was missed.

Sir Donald Macdougal ventures the view that the most important factor causing stagnation in exports was that India depended heavily upon commodities such as tea, cotton textiles and jute whose exports in the world as a whole had been expanding only slowly if at all.

For instance, between 1948-60, the volume of world exports in tea rose by 28%, of cotton by 17.9%, of tobacco by 37.2% and castor (oil and seeds) by 20% in contrast to 117% rise in the volume of total world exports of all commodities.

This alone, however, cannot be a satisfactory explanation because while Indian exports remained almost stationary, other countries like Hong Kong, East Africa, Thailand and Pakistan increased their shares in these very traditional items.

The pervasive failure in respect of the traditional items, in Benjamin. I. Cohen’s view, was largely due to the fact that prices of Indian products tended to be higher than those of her competitors on account of a higher rate of inflation, low level of efficiency and cost un- consciousness in India.

As cairncross points out, prices of natural materials are often an important factor in determining the pace at which synthetic substitutes are introduced. The prices of our exports, traditional as well as non-traditional, were higher and there is no doubt that this played a role, even if a subordinate one, in promoting a growing use of synthetic substitutes for jute, cotton-textiles etc. in foreign markets.

According to Dr. Cohen , the situation was worsened by “policies adopted by the Indian Government to achieve goals which has a higher priority than export promotion.” Mention may be made, in this connection, of export controls, Export duties and the pressure of home demand which acted as limiting factors.

For instance, as late as 1960, commodities like tea, raw-cotton, raw wool, iron and Manganese ores, raw-hides and skins, vegetable oil seeds and oils could be exported only within quantitative ceilings as prescribed by export control authorities.

Many of the major items of exports like the manufactures, tea, cotton textiles and vegetable oils were subjected to export duties which played no insignificant part in restricting India’s exports.

To cite one example, exports of manganese ore from India were subjected to a 15% advalorem duty. The adverse effects of this duty were not immediately visible because of the Korean war boom and stock- piling programmes in the importing countries. Soon afterwards, it was found that the USSR and other exporting countries had utilised the opportunity to enlarge their share of the European market.

In the cotton textile industry, export promotion came in conflict with providing employment opportunities and the interests of the handloom sectors. Similar conflicting policy decisions encouraged the jute industry of Pakistan.

A contributory factor was the regional distribution of India’s foreign trade. Until recently, India had important commercial relations only with a small group of countries like the U.K., the U.S.A. and a few others whose rates of development were relatively low.

Had India diversified her trade relations by forging connections with the East European countries and the newly developing countries of Africa and Asia, her exports would have expanded faster than they actually did.

According to Ragnar Nurkse the expansion of external demand for the primary commodity exports of the poorer countries appears, in recent years, to have lagged behind the rate of increase in both the exports and national income of the industrial countries.

This is borne out by the fact that the share of the developing economies in the total world export declined from 31% in 1950 to 20% in 1966 while that of the developed economies went up from 60% to 68% and of the centrally-Planned economies from 8% to 11%.

It, in other words, means that the developed countries tended to trade among the themselves than with the underdeveloped ones. And the reasons for this were not economic alone but political as well. Commerce indeed was becoming less a matter of business and more of politics. The remarks made by Prof. Halstein, President of the common Market commission, are significant in this connection.

Addressing the Harvard University, he confessed, “we are not in business to promote tariff preference —or to force a large market to make us richer or a trading block to further our commercial interests. We are not in business at all; we are in politics.” It is clear, therefore, that political reasons constituted another factor hampering the export efforts of all developing countries including those of India.

Imports:

During the First Plan, the development and investment activities were still in doldrums. That is why the value of imports fell from Rs. 650 crores in 1950-51 to Rs. 610 crores in 1953- 54. The Year 1953-54- represented a nadir of India’s foreign trade. Thereafter, there was a steady rise which gathered momentum with the intensification of developmental efforts around 1955.

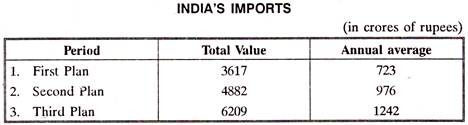

As a result, imports increased from Rs. 3617 crores in the First Plan to Rs. 4882 Crores in the Second and Rs. 6209 crores in the Third Plan. It, in effect, meant that during the second Plan, imports rose by 34% over those in the First and during the Third, by 27% over those in the Second.

The heavy imports during the Second Plan were due to:

(a) Large- scale imports of capital goods to develop heavy and basic industries;

(b) The necessity of making “minimum maintenance imports” for a developing economy; and

(c) The failure of agriculture production to rise to meet the growing demand for food and raw- materials which necessitated large imports of these articles.

One point, however, must be emphasised. It is being too readily assumed that industrialisation of the country necessarily involves high level of imports.

It certainly does within certain limits, but it does not follow, as Prof. Gian Chand argues, that we must import crores worth of mineral fuel, fruits and vegetables every year and that their consumption must keep growing even if for these and similar imports, we had “to mortgage our future and acquire in the disquieting prospect of meeting of Aid-India Club having to be convened for an indefinite period”.

The view that our imports could be considerably reduced had we really perused the aim of reducing them to an austerity level with greater zeal is a valid one. Intermediate- goods, known to be goods for maintaining production, were found of hide many non-essentials which the country could well do without.

It is also amazing to dind that although the production of some goods such as machine tool and caustic soda increased substantially, the increase did not always bring about a decline in the total amount of imports required.

Thus, we find that during the ten years covered by the Second and Third Plan, massive investment outlays resulted in more than a doubling of India’s imports, implying an annual, growth rate of 7.9%. During the same period, exports increased tardily at an annual rate of about 3.1%.

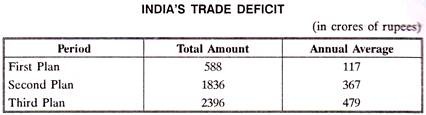

With imports running ahead of exports, the ratio of the latter to the former experienced a declining trend, On an average, exports financed 83.7% of the imports during the First Plan, 62.4% during the Second and 61.5% during the Third. As a result, India’s export deficit increased from Rs. 82.52 crores in 1955-56 to Rs. 584.50 crores in 1965- 66.

In the normal text-book situation, imports and exports are two independent variables which together determine the value of trade balance. In India, import was not an independent variable because its volume was determined more or less in advance by the authorities through the import licenses issued.

Generally, the authorities took care of ensure that the value of the import licenses issues over a certain period was roughly equal to the sum of the expected export earnings and the expected volume of utilizable external assistance. This explains why trade deficit kept on increasing up to 1965-66. One reason for this was that availability of aid was large and increasing.

Looked at from this angle, India’s trade deficits acquire a different significance. They measure the volume of inflow of real resources from the rest of the world. In other words, trade deficits measure the positive role played by the foreign trade in the economic development of India in the post- Independence period.

During the Second and the Third Plans, the import surpluses provided, on an average, resources equal to 2.6% of India’s Gross Domestic Product. Put in another way, these trade deficits were also a measure of India’s financial dependence upon other countries for her economic development.