In this essay we will discuss about banking in India. After reading this essay we will learn about:- 1. Joint Stock Banking in India 2. Exchange Banks of India 3. State Bank of India 4. Reserve Bank of India 5. Banking Regulation in India.

List of Essays on Banking in India

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Joint Stock Banking in India

- Essay on the Exchange Banks of India

- Essay on the State Bank of India

- Essay on the Reserve Bank of India

- Essay on the Banking Regulation in India

1. Essay on Joint Stock Banking in India:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There is both literary and epigraphical evidence establishing the antiquity of Indian banking. In Vedic literature, there are references to credit transactions. The Buddhist Jatakas of the 5th and 6th centuries B.C. make mention of moneylenders while Manu Samriti contains separate chapter on “Recovery of Debt” and “Deposits and Pledges.”

Kautalya’s Arthshastra generally prescribed 16-8% rate of interest except when the risk was extra-ordinarily high. There is also evidence to prove that deposit banking in some form had come into existence by the Second or Third century of the Christian era.

During the Mughal rule, the indigenous bankers did the profitable business of money-changing and most important among them were appointed mint — officers, revenue collectors, bankers, and money-changers to the Government. These bankers could not, however, develop the system of obtaining deposits regularly from the public and those, who made savings, either hoarded or lent them to friends and neighbours.

The English traders could not make much use of the indigenous bankers, firstly, because of the language difficulty and secondly, because Indian bankers lacked experience of the finance of European trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Therefore, the English Agency Houses, which were primarily commercial undertakings, began to conduct banking business also, so as to meet the needs of the company, the members of the services, and the European merchants in India.

Not all Agency Houses carried on banking business but a great many of them performed the three functions of:

(a) Receiving deposits,

(b) Paying drafts and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) Discounting bills thus paving the way for the establishment of joint-stock banks.

The earliest of these was the Bank of Hindustan set up by Messers Alexander and Co., in 1770.

Several other such banks were also established but during the crisis of 1829-32, many of the Agency Houses failed due to “gross- mismanagement, wild speculation and extravagant living “ on the part of the big merchant prices managing the Agency Houses. Between 1800-1858, more than 40 banks were established, bur hardly 12 of them survived.

A permanent institutional gain of this period was the emergence of the three Presidency banks of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras which had come into being in 1806,1840, and 1843 respectively. These Presidency Banks functioned as Government bankers enjoying even the right of note-issue till 1862, in which year this privilege was withdrawn.

The Presidency Bank Act prohibited these banks from lending for more than six months; from lending on the security of immovable property or from dealing in foreign bills and borrowing abroad. In return, most Government work was retained in their hands and the prestige so enjoyed enabled them to secure a large amount of other business also.

1860-1900:

The passing of the Act of 1860 marks a landmark in the history of joint-stock banking in India. Under this Act, for the first time, the principle of limited liability was accepted and this gave a new impetus to the development of banking. In 1865 was established the Allahabad Bank followed by the Alliance Bank of Shimla in 1875, both under British management.

The city of Bombay saw an extraordinary floatation of banks during the speculation fever of the American Civil War. As many as 25 banks with a paid-up capital of 13.6 crores of rupees and 39 financial associations came into existence in the short span of three years, 1863-65.

Unfortunately, all this financial and banking enterprise was a mere incident in the fantastic speculations in land and other forms of wealth prevalent at that time and, when the speculation itself collapsed, not a trace of many of these banks was left.

The first bank of limited liability management by Indians was the Oudh Commercial Bank, founded in 1881. Subsequently through the efforts of Lala Harkishan Lal, ‘the Napolean of Punjab Finance’, the Punjab National Bank was established in 1894.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Generally speaking, the period 1860-1900 was characterised by a very slow development of banking and banking habits. This may be seen from the fact that in the last three decades of the 19th century, the three Presidency Banks together with Indian joint stock banks added to their capital a mere rupees three crores and to their deposits only rupees 14 crores.

Prof. L.C. Jain is of the opinion that the uncertainties of exchange were mainly responsible for the slow rate of banking progress.

It is, of course, natural that instability of exchange should have caused much hesitation, additional cost, and difficulty in the financing of our foreign trade. Complaints to this effect were brought before the Herschell and the Fowler Committees. Nevertheless, it is most unlikely that exchange instability could have adversely affected the business of banks other than the highly developed exchange banks.

A more plausible explanation of the slow progress of banking may be found in the almost stationary economic conditions in the second half of the 19th century. Besides, indigenous manufactures with which the city-based banks were mostly concerned showed a continuous rise in prices during 1866—1886. This was obviously not suited to stimulate growth of deposits and banking in a backward country like India.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A third factor wast the important change in the currency system of the country brought about by the Currency Act of 1861. This Act gave the Government a monopoly of note-issue and thus put a brake on the growth of banking in the country.

The existence of competitive note-issue was the foundation on which countries like France and Germany raised their banking structure. The Act of 1861 thus closed the door on progress along the one line which promised quick results.

While the progress of banking in general was very slow till 1900, one section of the banking system, namely, the Indian joint-stock banks, passed through a remarkable phase during the last decade of the century. Indian joint-stock banks were hardly in existence in the period 1860-1880. During the next decade, they gained in size and strength.

It was, however, in the last decade that they made a substantial gain in their deposits. At the end of the century, there were only 9 banks with capital and Reserves of over Rs. 5 lakhs, their total paid-up capital and Reserves being Rs. 1.25 crores while total deposits amounted to a bare Rs. 8 crores.

1900 Onwards:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Swadeshi Movement which began in 1906 gave great stimulus to banking and, during 1900-1913, the number of banks with capital and reserves of over rupees 5 lakhs increased from 9 to 18 with paid-up capital and reserves of rupees four crores and total deposits amounting to rupees 22 crores.

The number of smaller banks, established during this period, was even greater. Some of the prosperous banks of today, the Bank of India, the Central Bank of India, the Bank of Baroda, and the Bank of Mysore were established during this period. This boom was followed, during 1913-16, by a banking crisis which was the severest and most disastrous till then.

During the years 1829-32, 1857, and 1863-66, there were indeed several bank failures and much capital was lost. In the crisis of 1913-16, 87 banks representing 34% of the total paid-up capital of all Indian joint-stock banks failed.

Majority of the banks, which failed, were small and weak but at-least half a dozen of them were large. The crisis was aggravated by the jealousy of European banks who, as Shirras point out, refused to lend a helping hand. This crisis was caused by a number of factors.

In the first instance, a large number of mushroom banks, which had rapidly expanded before the war, had conducted their business in violation of elementary principles of banking. As Keynes points out they were not content to build up their business in the usual ‘slow but sure way’ but undertook varied types of business including ‘coach-building, medical attendance’ and, of course, industrial finance.

They had an imposing authorised capital but their subscribed capital was small and the paid-up capital was smaller still. The law did not prevent this malpractice and the banks took ‘advantage of it to deceive the public’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The deficiency of capital made these banks wholly dependent upon deposits for conducting their business. They often offered much higher rates of interest than they could really afford. In order to be able to pay the high rates of interest on deposits, large sums were locked up in speculative dealing in silver, pearls, and other commodities.

Some banks advertised such advantages as ‘Special Marriage Deposits’, “50% added to principal in 5 years”

Many of the managers and directors of these banks were incapable men and had little knowledge either of the principle or the practice of banking. In the words of Shirras, “It was a case of an army going into battle without any trained officers and without any orders from the General Staff.”

Share-holders, on the other hand, were too ignorant or apathetic to exercise their rights to control either the directors or managers many of whom resorted to dishonesty, fraud or criminal mismanagement. To hide it, window-dressing was often made use of in making up the balance-sheets. In a few cases, dividends were paid out of capital and, if that had disappeared, out of deposits.

It is, therefore, not surprising that very low cash reserves, amounting to no more than 11% of the liabilities, were kept. These reserves were hopelessly inadequate to serve their purpose in a country like India where the banking habit was far from being formed.

The crisis was aggravated by a complete absence of co-operation between the Indian joint-stock banks themselves and between them and the Presidency and exchange banks. This was, as M.M. Malviya explains, because there was no central bank which could guide the general banking policy of the country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These were the causes of the failure of mostly the small banks which had rapidly sprung up after 1904. Their failure did much to weaken public confidence in Indian joint-stock banking and thus gave considerable set-back to banking development in India. However, some of the older and larger Indian banks conducted their business on sound lines and were able to withstand the crisis without adverse consequences.

The boom during the later part of First World War and immediately thereafter led to the establishment of a number of new banks, some especially for financing industries. The most important of these was the Tata Industrial Bank.

The war also saw a remarkable increase in the deposits of the commercial banks. The large profits earned by trade and industry during the war years as well as the rise in Government expenditure led to deposit-expansion from rupees 17 crores in 1914 to rupees 46 crores in 1921.

But from 1922, owing to economic depression, the number of failures increased, with as many as 373 banks having failed during 1922-36. The most important failures were the Alliance Bank of Shimla, The Tata Industrial Bank, and the People Bank of Northern India.

Banking Enquiry Committee:

Dissatisfaction with the progress of banking led to the institution of a comprehensive banking Inquiry in 1929. In the first instance, ten provincial committees, composed of persons having intimate knowledge of local conditions, dealt with agricultural and cooperative credit, mortgage banks, and credit — problems of small-scale industries.

Nineteen of the Indian states appointed similar committees for their own territories.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the second stage, an All-India Committee coordinated the work of the above committees and itself examined those aspects of banking as related to provision of credit for India’s chief industries, banking regulation, and banking education, which has been excluded from the purview of the Provincial committees.

The Provincial committees issued their reports in 1930, and the central committee in 1931. The central banking committee tackled a wide-range of problems which, in the words of Sir Purshottam Dass Thakur Dass affected “vitally not only the prosperity of the masses but even their very existence.”

With regard to the organisation of banks, the committee suggested that the banks should aim at combining the efficiency of the European system with the economy of the indigenous bankers. It recommended opening of new branches at places where there was no joint stock bank and also the opening of sub-offices or part time branches in smaller centres contiguous to places where there were regular branches of banks.

Another important recommendation was that no new branch should be opened without the approval of the Reserve Bank which should not only grant licences freely to the already established banks but should also see that the legal requirements were fully-satisfied.

With regard to the business of these banks, the committee recommended that they should extend the system of advances against precious metals and personal credit of borrowers. The committee further recommended that, with the establishment of the Reserve Bank of India, the banks should make every possible effort to provide cheap remittance facilities to the public.

With a view to arriving at a better understanding of their common problems and interests, the committee recommended that the Exchange banks, the Imperial Bank of India, and the indigenous banks should all form an All India Bankers’ Association.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As regards banking education, the committee recommended that every university should provide for the training of students at recognised institutions by courses for commercial degrees, while systematic instructions in elementary accounting, discount, cooperative principles, and elementary banking should be given in secondary schools.

As for their regulation, the committee recommended that a special Bank Act should be passed which should cover organisation, management, audit and liquidation of banks.

Besides, the Act should provide for:

(a) Prohibition of the organisation of a bank on the managing agency system;

(b) A minimum paid-up capital of Rs. 50,000. The Committee further laid down that the paid-up capital should never be less than 50% of the subscribed capital and the subscribed capital should never be less than 50% of the authorised capital of a bank;

(c) Allocation of at-least 2½% of a bank’s profits to a Reserve Fund until the fund equals paid-up capital;

(d) The grant of moratorium in times of financial difficulties on the recommendation of the Reserve Bank;

(e) Specific liabilities of Officers and directors for commission of material facts in their reports and accounts;

(f) Protection of the creditors, interests in case of compulsory liquidation.

The committee also recommended that all banking companies, incorporated under the proposed Bank Act should make provision, in the Memorandum and Articles of Association, regarding:

(a) Prohibition of activities other than banking;

(b) Grant of loan on the security of a bank’s own stock;

(c) Restrictions on the grant of loans to directors, managers, and members of the staff of a bank

(d) Qualifications for appointment, retirement and voting powers of directors and officers of banks.

These recommendations of the committee, were embodied in the Indian Companies (Amendment) Act, 1936. Meanwhile, the establishment of the Reserve Bank, in 1935, fulfilled a long standing demand and removed a major lacuna of the Indian Banking structure.

The period before the Second World War may be summed up as one of expansion and slow consolidation. In 1936, there were 42 scheduled and 71 non-scheduled banks with capital and reserves of Rs. 50,000 and above. Their capital and reserves came to Rs. 14 crores, deposits amounted to Rs. 103 crores and their cash balances came to Rs. 15.28 crores. The total number of Banking offices reached 1450.

This expansion of banking facilities was rather haphazard in as much as only 14% of the towns having population between 10 — 20 thousand had a banking office while 62% of the large towns with population of 20,000 and above, enjoyed this facility.

Area-wise, banking offices were fairly distributed in the Punjab, the U.P. and the three presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. In other parts of India, especially Bihar, Orissa, the Central Provinces, Assam and most of the Indian states, the banking facilities were in adequate.

The expansion, though impressive in absolute terms was, when compared with other countries, meagre. In 1936, population per banking office in India was 2,76,000 as compared with a mere 3900 in England and Wales and 7900 in U.S.A.

Similarly, the deposits per head in India come to a little over 10 Shillings as against 212 in Germany, 275 in Switzerland, 1164 in England and 1317 in U.S.A. There is no doubt that the smallness of the per head deposits was caused more by the lack of banking facilities than by the poverty of the country.

Joint-Stock Banking during World War II:

The immediate effect of the war was certain amount of hurried withdrawals from the banks. This, however, proved to be a temporary phase and the public soon adjusted itself to the new situation. From 1942, joint-stock banks began to take rapid strides.

The number of scheduled banks increased from 51 in June, 1939 to 93 in June, 1946 while the number of branches rose from 1959 to 5521. Deposits increased from Rs. 238 crores at the commencement of the war to Rs. 1097 crores at the end of 1946.

There were several reasons for the rapid expansion of commercial banking during 1942-46. Firstly, banking was still in the early stages of growth and, therefore, had large scope for expansion. Secondly, expansion of currency resulting from war-finance made enormous funds available for investment.

These funds could not be used for establishing industrial concerns due to the difficulty of obtaining machinery and industrial equipment. There was. however, no difficulty in establishing new banks.

In the words of T.A. Vaswani , “Any financial adventurer, who required money for speculative ventures, started a bank with numerous branches and collected substantial deposits, by offer of high rates of interest and by lavish advertising.”

The largest among the new banks, established during this period, were the United Commercial Bank and the Bharat Bank sponsored by the houses of Birla and Dalmia respectively. Thirdly, the public was not willing to convert its savings into durable assets such as gold, real estate on account of their inflated prices.

A more welcome development was that despite this growth, the Indian sector of the banking system as a whole emerged stronger than before. Between 1941-45, of the total deposits, the percentage held by the exchange banks fell from 29 to 17, that held by the Imperial Bank declined from 31 to 24 while that held by Indian joint-stock banks increased from 40 to 59.

As a result of this phenomenal expansion of deposits between 1939-45, the percentage of the paid-up capital and reserves to Bank deposits declined from 10.8 to 7 in the case of the Indian Joint-stock banks and from 12.8 to 4.5 in the case of the Imperial Bank.

This unfavorable factor was neutralized only in part by the higher percentage of liquid assets which banks were forced to keep on account of war conditions. Some banks even increased their capital with the sanction of the Government.

As easy money conditions prevailed throughout the war, only a small number of banks, not more than a dozen in any year, needed financial accommodation from the Reserve Bank. Banks earned enormous profits and some of them had even to pay Excess profits Tax.

Although the progress of banking was rapid and substantial during the war, it was not free from defects. New as well as old banks experienced considerable shortage of trained employees. Untrained and sometimes incompetent men were indiscriminately appointed to fill the highest offices requiring technical knowledge and long banking experience.

Accordingly, the management of many banks was neither strong nor independent. The most serious defect, however, was the indiscriminate opening of branches in areas already well served.

There was unhealthy and wasteful competition among too many banking offices in some parts and centres while other parts of the country remained totally neglected. Other defects were the acquisition of the control of non-banking companies, interlocking of banks and other concerns, undesirable manipulation of accounts and utilisation of profits for paying dividends instead of building reserves.

Apart from these, the advances portfolios of the banks were unsatisfactory in as much as either the advances were granted against undesirable security like immovable property and speculative shares or without any security at all and most of such advances were allowed to friends or persons connected with management.

There was a large divergence between authorised and subscribed capital on the one hand and subscribed and paid-up capital on the other.

This indiscriminate and uncontrolled expansion was bound to create trouble and, between 1939-45, as many as 482 banks with a paid-up capital of Rs. 94 lakhs failed in various parts of the country. Besides paralyzing many small depositors, these large failures adversely affected the confidence of the people in the banking system.

The Partition of the country in 1947 gave a further jolt to the banking system of the country. Bank advances declined on account of communal disturbances in several parts of the country. Banks, having their head offices and branches in West Punjab, were hit hard for they could not transfer their assets to the Indian Union.

At such a time, the Reserve Bank came to their rescue by making advances against any security which it thought proper. The Government also made rupees one crore available for rehabilitating these uprooted banks.

Progress since Independence:

The Post-Independence period marks the beginning of a new era in the history of Indian commercial banking. What could not be achieved in the first fifty years of the twentieth century, was achieved in a span of less than 20 years. Prior to the Independence, the growth and development of Indian banking was both unplanned and uncontrolled as a result of which many banks failed bringing lakhs of depositors to grief.

Besides, these recurring bank failures dealt a severe blow to public’s confidence in the banking system of the country. With a view to avoiding such recurrences in the further and to putting the banking legislation was adopted in the year 1949. The Banking Regulation Act, 1949, vested the Reserve Bank with sweeping powers to control, regulate, supervise and direct the banking system of the country.

The same year, the Reserve Bank passed into public ownership to discharge its duties more efficiently and effectively in the context of economic planning in the country. All these developments, taken together, brought about major changes in the nature, structure, and functioning of joint stock banks in the country.

The post-Independence period may be broadly described as one of consolidation and all-round progress. The number of banks came down from 566 in 1951 to 100 at the end of 1966, of which 73 were scheduled and 27 non-scheduled banks.

This change came about as part of the overall strengthening of the banking system. Through the licensing policy, the weak and sickly banks were either weeded out or amalgamated with stronger ones.

While the number of banks thus went down, the number of banking offices, by contrast, shot up from 4151 in 1951 to 6596 in 1966. Even here, the overall trend was towards a strengthening of the base of the banking industry in as much as the number of offices of scheduled banks increased from 2647 to 6383 while those of the non-scheduled banks actually declined from 1504 in 1951 to a mere 213 in 1966.

Significantly, the population covered per banking office came down from 87,000 in 1951 to little over 73,000 in 1966. What is more, banking facilities were expanded in smaller towns and villages. In 1965, 890 centres with population of less than 10,000 had banking facilities while the number of offices at places, with population ranging from 10,000 to 50,000 rose to 2010.

From the operational point of view, joint-stock banks made remarkable progress in attracting more and more deposits and advancing more loans.

Scheduled Banks deposits increased from Rs. 804 crores in 1949 to Rs. 3,123 crores in June, 1966, indicating an average annual growth rate of over 19%. Average deposits per branch of a scheduled bank rose from Rs. 32 lakhs to Rs. 56 lakhs while deposits per capital increased from Rs. 25 in 1951 to Rs. 73 in 1966.

Commensurate with the increase in deposits there was an expansion of bank credit which shot up from Rs. 439 crores in 1949 to Rs. 2286 crores in June, 1966.

A distinguishing feature of these advances was that industrial advances of scheduled banks increased appreciably from Rs. 30.4 crores in 1949 to Rs. 1471 crores in 1966, constituting 63% of the total bank credit. By contrast, advances to commerce formed only 24% of the total credit, thus indicating a clear shift in bank lending’s from ‘Profitable’ to ‘Productive’ channels.

Another new feature of the bank credit was the decline in the seasonality of bank credit. In the past, bank credit, in the busy season, used to go up by about Rs. 50 —100 crores while, in the slack season, there was a flow-back of funds to the banking system almost to the same extent. This was no longer a constant phenomenon, thanks to the diversification of the economy and general stringency of credit.

The qualitative progress of banking was all the more remarkable if we note the fact that the Indian banks took to more sophisticated forms of banking business like ‘term-finance’, foreign exchange, export finance, credit cards, inland travellers cheques, trustee work, and furnishing of guarantees.

Another healthy development was the coming together of banks to end unhealthy competition so far deposit rates were concerned. A gentlemen’s agreement, called the Inter-bank Agreement, was signed by 1958 on maximum rates of interest payable on deposits. Following the failure of the Laxami and Pilliai Bank in 1960, the scheme of ‘deposit-insurance’ was introduced with a view to giving protection to small depositors.

It was also realised that “we shall have good banks not when we have good laws but when we have good bankers.” Accordingly, greater attention began to be paid to banking education. A banker’s training college was set up by the Reserve Bank in 1954. Similar institutions were set up by several banks to train and educate their own staff.

Despite this spectacular progress in several fields, the over all growth of banking facilities was still small when compared with other countries. For instance, even though the population per banking office came down to a little over 73,000, it was disproportionately large in comparison with 4,000 in Britain, 7,000 in U.S.A. and 15,000 in Japan. What was more disturbing was that the coverage was not uniform.

States like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madras, and Andhra had fairly well-developed banking system whereas states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, U.P., and West Bengal had comparatively poorer facilities. There was also a glaring disparity between the rural and urban areas in respect of banking facilities. Out of 5,64,000 villages in the country, less than 5,000 had the facility of a commercial bank’s service.

Coming to the functional aspects of commercial banking, the growth in deposits was due, to a large extent, to the rise in public expenditure and deficit-financing.

Significantly, the percentage of deposit money to total money-supply increased only marginally from 30.5 in 1950-51 to 35.5 in 1966-67, indicating that the deposit component of money supply did not go up. This meant that there was considerable scope for developing the banking habit and the deposit potential of the country.

A far more disquieting aspect of credit expansion was that its distribution and direction were not in tune with the promotional objectives of the role of banking as a service industry in a modern welfare state. Deposits were largely used to provide credit facilities to the urban sector, much to the neglect of the backward regions.

Deposits realised from poorer and backward states were diverted to highly developed states like Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu, these three states, among themselves, accounting for as much as 55% of the total credit of the banking system.

Population-wise data regarding deposits and advances for the year 1966 indicates that while the rural centres contributed 3.6% of the total deposits of the scheduled banks, their share in the total credit amounted to only 2.1%.

Semi-urban areas, with population of 10,000-50,000 contributed 15.4% of the deposits but accounted for only 10% of the total credit. Thus, far from supplementing the resources available for lending in rural areas, the operations of commercial banks resulted in a diversion of resources mobilised in the rural areas to the urban sector.

It is most unfortunate that the share of agriculture, contributing 51% of the National Income in 1964 — 65, remained stationary around 2-3%. If the plantations are excluded, the share amounted to a more 0.5%.

On top of all this was the fact that, in the process of growth, the capital base of the banks had deteriorated. This is evident from the fact that the ratio of the paid-up capital and reserves to deposits declined from 10% in 1951 to just 3% in 1966 despite the fact that the Reserve Bank had enjoined on the commercial banks, as early as 1961, to aim at a reserve base of at least 6%.

In the face of it, it is remarkable, though not surprising, that the ratio of profits before tax to paid-up capital and resource increased from 12.2% in 1951 to nearly 34% in 1966, not withstanding a ten-fold increase in operating costs.

Another disturbing aspect of banking development in the post-Independence period was the continued and increasing role of these institutions in furthering the concentration of economic power in a few hands.

Dr. R.K. Nigam in his study of 20 big banks, found that the directors of the Five-Big banks were, through common directorships, related to 33 insurance companies, 25 investment banks, 6 financial companies, 26 trading companies, 15 non-profit associations and 584 manufacturing companies.

These facts lend powerful support to the view that the emergence of monopolies in the country owes much to the control of banks and other financial institutions by a handful of families. In addition, they furnish an irrefusable argument in favour of total bank nationalisation.

2. Essay on the Exchange Banks of India:

Exchange banks have been officially defined as those “whose had offices are outside India.” In western countries, the phrase exchange banks included those banks which were “specially concerned with financing the trade of India and China which countries, not having a gold standard, have exchanges peculiarly liable to fluctuation”

Many Indian writers, however, regard the phrase as misleading because these banks do not restrict themselves to financing India’s foreign trade only; they play a large part in financing her internal trade as well. Moreover, Indian joint-stock banks are also free to do exchange business. They, therefore, prefer to simply call them ‘foreign banks.’

These banks may be classified into two categories:

(a) Banks which were no more than agencies of large banking corporations doing business all over the world. Their Indian business amounted to no more than a small fraction of their total business. The Bank of Taiwan, The Mitsui Bank, The International Banking Corporation belonged to this category.

(b) Banks doing a considerable portion of their business in India. The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China (1853), The National Bank of India (1863) and The Mercantile Bank of India (1893) were amongst the biggest of such banks.

The main function of these banks was to finance the foreign trade of the country although they did all kind of banking business. For example, they competed with Indian joint-stock banks in receiving lock deposits and making advances.

The piece-goods trade in Delhi and Amritsar, the leather trade of Kanpur, and jute trade in Bengal were largely financed by these banks. They also encouraged tourist traffic through the issue of Travellers cheques. They also acted as Reserve Bank’s authorised dealers of foreign exchange.

The exchange banks, having established a very strong position and a great reputation for themselves, were extremely jealous of outsiders. In Keynes view, “Indian Exchange Banking is no business for speculative or enterprising outsiders.”

Realising the manifold difficulties, he opined that it would be exceedingly difficult to start a new exchange bank except with the backing of some important financial house already established in a strong position in India.

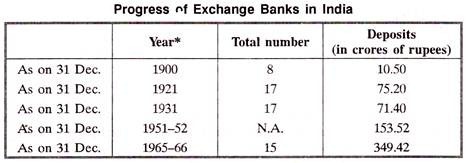

It is, therefore, not surprising that in-spite of the open-door policy maintained by the Government for 3/4 of a century, the number of exchange banks remained rather small, there being 8 banks in 1900 and 15 in 1965.

There was, however, a rapid increase in their deposits from Rs. 10.5 crores in 1900 to Rs. 349 crores in 1965-66. Since the number of banks remained constant, the average deposits per bank rose very fast. Another noteworthy aspect of the working of these banks was their low cash-reserve ratio.

As early as 1913, Lord Keynes’ had found in this practice of keeping low cash reserves by exchange banks a major threat to the Indian banking system. The position since then, if any thing, further deteriorated. Cash as a % age of deposits came to 5.59% in 1960-61 and 4.48% in 1965-66.

The working of the exchange banks invited much criticism some of which was even brought to the notice of the Central Banking Enquiry Committee. One complaint was that the exchange banks, until very recently, were not subject to any legal restriction in India, not even to the statutory obligations to which Indian joint-stock banks were subject.

They obtained a large portion of their funds from Indians in the form of deposits but these deposits were not protected, until very recently, by any regulations. The depositors had no prior claim on the assets of the exchange bank in case it got involved into serious difficulties in another country owing to a crisis, fraud, or some other reason.

As S.K. Muranjan explains, the monopolistic position of the exchange banks in the sphere of foreign trade put the Indian to a double-loss of banking as well as trading profits.

They enabled Europeans to earn extra profits in the shape of brokerage on goods sold and purchased, freight and insurance charges. It was also pointed out that, in other countries, these banks supplied their customers with reliable and valuable information regarding foreign markets and prices prevailing there, the exchange banks in India did precious little to supply any information of this kind to their customers.

The Indian exporters, having no trade connections abroad, therefore, were greatly handicapped. It was also alleged that these banks did not supply satisfactory reference in respect of Indian merchants to overseas firms.

Besides, in order to get a confirmed letter of credit opened, even first class Indian importing firms were required to make a deposit of 10-15% of the value of the goods while European houses needed to make no such deposit. Another major complaint was that these banks discouraged Indian enterprise in several directions.

They compelled Indian exporters to insure their goods with foreign insurance companies as a result of which Indian insurance companies annually lost about 2-3 crores of rupees. They also hampered the development of Indian joint-stock banks.

Being long and well established and enjoying good reputation, they attracted deposits at cheap rates and could often under-bid the Indian banks by quoting lower lending rates What is more, these banks, through their influence in the Clearing Houses of the principal Indian financial centres, kept the Indian banks out of these houses for as long as they could and this exclusion adversely affected their reputation.

The strong position of the exchange banks and their monopoly of India’s foreign trade were partly responsible for splitting up the Indian money-market into two parts, Indian and European. The gulf between the two and their ignorance of the doings and methods of each other hampered the economic progress of the country.

Another major complaint was that, until after Independence, hardly any Indians were appointed in the superior grades of services except as cashiers and clerks.

They made no arrangement for the selection of qualified Indians as apprentices for training and appointment in the officers grades; instead , they preferred importing their officers from abroad and paying them high salaries. Indian intellect was thus denied an opening to which it had every right.

The financing of India’s imports as well as exports was by means of Sterling Bills and Indian importers could do business only on Documents on Payment terms. This was peculiar to Indian trade, and, incidentally, responsible for the lack of a bill market in the country. As pointed out by the Central Banking Enquiry Committee, “for the import business of India, the natural bill market is in India and not outside India.”

Notwithstanding these complaints, it must be admitted that the exchange banks developed India’s trade at a time when no banking agencies were available. Regarding the provision of finance to foreign trade, these banks did a good job in the past and also in recent times.

Their service was efficient though not cheap as claimed by Mr. L.C. Jain. Despite the fact that these banks obtained large deposits in India at low rates and rediscounted their bills in the London Market at still lower rates, Indian importers and exporters had to pay higher rates for financial accommodation than their counterparts in western countries.

As Panandikar points out, while the discount rate in western countries is lower than the bank rate in India, the exchange banks kept it higher than the bank rate.

It was suggested to the Central Banking Enquiry Committee that the real and lasting solution of the problem of Indian foreign-trade finance lay in the establishment of ‘joint-banks’ controlled by Indians and non-Indians, belonging to the countries with which India traded as equal partners.

The committee approved of this idea as one promoting goodwill and co-operation among nations but expressed the opinion that the idea could not be enforced by means of legislation but was one primarily for the shareholders and directors of the banks to carry out.

This recommendation was impracticable because there was no chance of exchange banks ever accepting it while Indian banks could not provide the large amount of capital which was required. Realising these difficulties, the committee favoured that the Imperial Bank should be induced to develop foreign exchange business failing which the Government itself might set up an Indian exchange bank.

Six members of the committee, in a minute of dissent, argued in favour of a full-fledged ‘State Exchange Bank’ because, in their view, the situation created by the monopoly of the exchange banks was so difficult that it was essential to bring the full resources and prestige of the state to bear upon it.

However, the need for such a bank diminished with each passing year as the exchange banks, realising the changed political conditions after Independence, became more accommodating while Indian banks grew stronger.

On one point, the committee was unanimous, namely, that the policy of open-door to foreign banks in India should be abandoned. On the other hand, it recommended that these banks should be regulated through a system of licensing.

Before 1949, there were no restrictions on the activities of the exchange banks except those of a very general nature imposed under the Indian Companies (Amendment) Act, of 1936. The Act of 1949 was the first to regulate their working.

In addition to conditions regarding licensing, loans and advances, opening of branches, maintenance of cash-reserve ratio, inspection etc., which were applicable to both Indian and foreign banks, the Act imposed certain special restrictions on exchange banks, mainly with a view to safeguarding the interests of the Indian depositors.

These were:

1. That banking companies, incorporated outside India, must have a minimum paid-up capital and reserve of Rs. 15 lakhs and in case they had a place of business in Bombay and Calcutta also, of Rs. 15 lakhs.

2. That the first charge on the amount deposited with the Reserve Bank by a foreign bank would be, in case of liquidation, that of the Indian depositors and Indian creditors of the Bank.

3. That foreign banks must prepare a yearly statement of profit and loss in respect of business transacted in India.

4. That each foreign bank must have in India assets of not less than 75% of its Indian demand and time liabilities at the close of each quarter.

By 1966, these banks had become a part of the organised commercial banking system. There were few privileges left to the foreign banks and even those that continued legally were more formal than real. The objectionable features of these banks and their methods of financing had become part of history with little practical significance.

The trade was largely controlled and command over foreign exchange severely limited.

In short, banker’s role in determining preferential allocation of benefits of finance in the field of foreign trade was practically nonexistent, more so with the growth of bilateralism in trade and rupee-payment agreements for imports.

Foreign banks have a valuable part to play so long as the Indian Banks are not able to establish sufficient number of foreign branches.

Till then, there is no reason why India should not take full advantage of these banks which have large resources with widespread international connections and a network of branches all over the world, especially as, with a nationalized Reserve Bank of India, there is no difficulty in regulating their activity in national interest.

3. Essay on the State Bank of India:

The origin of the State Bank of India can be traced back to the Presidency Banks which came to be established in the 19th century. The first to be established was the Bank of Bengal in 1809 followed by the Bank of Bombay in 1840 and the Bank of Madras in 1843. One common feature of these banks was that they had a very close connection with the Government.

Of course, the bulk of their business was like that of any ordinary bank, namely, receipt of deposits and discounting of bills. But they also acted as bankers to the Government to a limited extent. They managed the temporary public debt of the Government and enjoyed the privilege of using Government’s balances up to a certain level.

When their monopoly was withdrawn in 1862, the Government, as a compensation, placed its cash balances with these banks at the Presidency towns. What is more important, up-till 1876, the Government not only contributed a part of their capital but also enjoyed the right of appointing some of their directors. A second feature of these banks was that they worked under strict control and regulations.

For example, they were prohibited from:

(a) Dealing in foreign bills and borrowing abroad,

(b) Lending for more than six months

(c) Lending on the security of immovable property.

These restrictions contributed to their strength and stability and they came to enjoy what Shirras calls the “prestige of antiquity and of official dignity.”

These Presidency Banks established branches at many important trade centres in India, the Banks of Bengal and Madres each having 26 branches while the Bank of Bombay had 18 branches in 1919. Their combined capital and reserves amounted to Rs. 7.5 crores, deposits, Government as well as public, to Rs. 83.17 crores and cash Rs. 26.74 crores.

Even though the Presidency Banks made satisfactory progress, yet they lacked mutual contact, the absence of which was strongly deplored. The banking crisis of 1913-17 forcefully brought out the defects and dangers of India’s free banking system under which there was no co-ordinated banking policy and each bank conducted its business in its own way without any control of a central institution.

There was also the danger of some non-British financial institution securing excessive influence and predominance in the monetary affairs of the country. It began to be felt that a close union of British and Indian interests could be ensured if the Presidency Banks could unite into a single bank and open a branch in London.

Public opinion was already urging the creation of a central bank. This impelled the Government and the Presidency banks to withdraw their opposition to the project and a special Act of 1920 amalgamated these banks into the Imperial Bank of India.

The Imperial Bank of India took over, from 27 January 1921, the three Presidency Banks of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras. It started with an authorised capital of Rs. 11.25 crores, of which half was paid-up and the other half formed the reserve liability of the share-holders.

The general superintendence of the affairs and business of the bank was entrusted to a Central Board of Governors which dealt with matters of general policy while the Local Boards, established at Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras, had power to deal with the ordinary day to day business in their respective territories.

A novel feature of the Scheme was that the Bank was allowed to establish a London Office which took over some, though not all, of the Government business previously conducted by the Bank of England.

This Office was allowed to borrow money in England for the purpose of the Bank’s business on the security of the bank’s assets but it was not allowed to open cash credits or receive deposits in London except from the former customer of the Presidency Banks.

Under the Act of 1920, the Imperial Bank of India acted as the sole banker to the Government, managed its public debt, and provided the machinery for the issue of Government loans. By virtue of size, resources, and wide connections, it also acted as banker’s bank and most of the leading banks in India, including exchange banks, kept a portion of their cash balances on deposit with it.

It supplied the supervisory staff to and managed the 11 Clearing Houses established in the principal cities of India. It provided remittance facilities to the public and banks at Government controlled rates.

Over and above these special functions, the Bank also performed the ordinary commercial banking functions such as receiving deposits, advancing money against accepted bills of exchange and promissory notes, or against goods or documents of title thereto deposited with or assigned to the Bank, borrowing funds in India and buying or selling gold and silver.

The Act did not permit the Imperial Bank to deal in foreign exchange or grant unsecured over-drafts in excess of Rs. one lakh. It was further prohibited from making advances for more than six months or on the security of its own stock or on the security of immovable property.

Further, the bank could not discount bills for, or lend or advance in any way to any individual or partnership firm, an amount exceeding at any one time Rs. 20 lakhs except against specified securities or goods or documents of title.

The hopes entertained of the Imperial Bank were not altogether belied. During 1921-28, the bank persued a vigorous policy of opening new branches, especially at places which had no banking office before. In 1928, it had 202 branches-more than twice the number of branches of all the exchange banks taken together and more than 1/3 of those of Indian banks.

Its reserve fund amounted to Rs. 5.40 crores while its private deposits alone came to 1/3 of the aggregate deposits of all banks taken together. The bank maintained a high degree of liquidity of its assets worthy of even a central bank. Its loans were kept within strict limits and a large proportion of its cash credits was terminable on demand.

The bank succeeded in reducing the difference between its own Hundi Rate and the Bazar Hundi Rate on the one hand and the rates of the Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras markets on the other. This imparted some elasticity to the credit system and stability to the business of the country. Moreover, the remittance facilities provided by the bank proved beneficial to the public and were extensively used.

With the establishment of the Reserve Bank of India in 1935, the Imperial Bank ceased to be a banker’s bank and banker to the Government. The Government, on its part, withdrew from the management of the bank except that it retained the right to nominate to the Central Board two non-officials.

Old restrictions on the business of the bank were withdrawn and the bank could henceforward transact foreign exchange business, open new branches, and undertake banking business of any kind including borrowing abroad.

It was allowed to buy bills of exchange payable abroad and of a usage not exceeding nine months in the case of bills relating to the financing of seasonal agricultural operations and six months in the case of other bills. The bank was permitted to acquire and hold, and generally to deal with any right, title, or interest in any property, moveable or immoveable, which might be the banks security for loans and advances.

Under an agreement reached between the Imperial Bank and the Reserve Bank, the former was to act as agent for the latter at all places where it had a branch but the Reserve Bank had none. The Bank was also to perform in those places the usual functions on behalf of Central and provincial Governments.

For these services, the Imperial Bank was to receive commission on the volume of transactions for the first ten years and the actual cost for the next five years and, if necessary, thereafter also. The agreement was subsequently revised.

In-spite of the creation of the Reserve Bank, the Imperial Bank continued to occupy a unique position in the banking and credit structure of the country. Although Government balances and certain other accounts were transferred to the Reserve Bank, its total deposits were still larger than the Indian deposits of all the exchange banks put together and not very much less than the deposits of all the Indian banks.

On account of its past position, immense resources, and great prestige, the Reserve Bank had to share control and guidance of the money- market with the Imperial Bank.

The Imperial Bank published a weekly statement of its affairs like the Reserve Bank and unlike all other banks even though the law did not require it. This statement, according to Mr. Ghosh, was as important as that of the Reserve Bank for a proper appreciation of the conditions of the money-market.

The Imperial Bank, as constituted in 1921, and its subsequent working were made the target of much adverse criticism. It was a private concern and especially open to suspicion on account of the strong representation of European interests on its management. There were allegation of racial discrimination in appointments and grant of financial accommodation.

Till 1930, all superior appointments were held by non-Indians whose high pay-scale rendered certain branches unprofitable and bank-services expensive. Indians were not only denied senior appointments but also did not get the accommodation to which their assets entitled them.

On the other hand, non-Indians were often given larger credit than that to which they were entitled on purely business principles. Although the Bank received help from the State and drew deposits of Indians, there was no provision in the Imperial Bank Act for securing due representation of Indians on its Central and Local Boards.

Again, on the basis of a close understanding between the Imperial Bank and the exchange banks, the Imperial Bank received on deposit much larger balances from the exchange banks, gave them larger overdrafts, acted as their agent in the interior for the collection of bills and cheques, and managed the clearing houses the majority of whose members were exchange banks.

On the other hand, its attitude was much less friendly towards the Indian joint-stock banks which bitterly complained of unfair competition at its hand. The Allahabad Bank, in particular, was loud in its outcry that, by being a banker to the Government, the Imperial Bank was placed in a special category and it was difficult for other commercial banks to complete with it.

It was also alleged that the bank used its branches more for collecting deposits in the interior than for financing trade. The method employed to secure the extension of banking facilities in India, viz. providing the Bank exclusively with interest-free Government balances and encouraging it to establish new branches, was also regarded by many as unduly costly.

A part of the criticism was certainly unwarranted. The complaint of unfair competition with other commercial banks itself was exaggerated. Nearly 50% of the branches of the Imperial bank were at places where no other bank had an office.

Competition arose, therefore, only at places where there were branches of the Imperial bank and other banks also. As regards interest-free Government balances, they never exceeded 12% of the private deposits of the Bank.

The Imperial Bank’s high rate of gross profits, therefore, was largely due to its ability to attract deposits at lower rates on account of the greater public confidence which it enjoyed. Similarly, complaints of discrimination in the matter of financial accommodation could not be substantiated. In 1925, 67% of individual deposits and 68% of the advances came from and went to Indians.

Of the deposits of the bank, 1/4 belonged to Indian banks, but of the advances, more than half went to Indian banks. It was, however, the supreme direction of the Bank which remained in non-Indian hands. Of the Directorate in 1936, 11 were English and only 4 Indians. Likewise, senior appointments were mostly held by Europeans while Indians were by and large, employed as clerks and cashiers.

In view of the strong and persistent criticism of the working of the Imperial Bank, the Finance Minister of the Government of India announced, in February 1948, the Government’s acceptance of the policy of nationalizing it along with the Reserve Bank. The decision, however, was not implemented.

Later, the Rural Credit Survey committee recommended the conversion of the Imperial Bank into the State Bank of India with the object of creating “a strong, integrated, state-sponsored, state-partnered commercial banking institution with an effective machinery of branches spread over the whole country which, by further expansion—can be put in a position to take over cash work from non-banking treasuries and sub-treasuries, provide vastly extended remittance facilities of cooperative and other banks — and generally — follow a policy which — will be in effective consonance with national policy as expressed through the Central Government and the Reserve Bank.”

The Government accepted the recommendation and the Parliament gave effect to it by passing the State Bank of India Act, 1955. At the time of taking over, the Imperial Bank had 474 branches and accounted for 23% of the total deposits, 20% of advances and bills discounted and 25% of the investment of all banks put together.

The State Bank of India started functioning from July 1, 1955. The shares of the Imperial Bank were transferred to Reserve Bank and the share-holders were given compensation or the option of taking up the shares of the State Bank of India in lieu of the above compensation.

Under the Act of 1955, the State Bank was empowered, with the Government’s sanction, to acquire the business of other banks, including certain state-associated banks, by paying compensation to their share-holders.

The State Bank of India (Subsidiaries) Act, 1959 enabled it to take over 8 state-associated banks as its subsidiaries. The Act of 1955 further imposed a statutory obligation on the Bank to open at-least 400 branches in the first five years of its existence.

In order to meet the losses due to the opening of unprofitable branches, the Act constituted an Integration and Development Fund into which were to be paid the dividends payable to the Reserve Bank and also such contributions as the Central Government or the Reserve Bank made from time to time.

Although essentially a commercial banking institution, an important objective set before the State Bank was “the extension of banking facilities on a large scale, more particularly in the rural and semi-urban areas.” This called for both an unrelenting drive and imaginative leadership. Against a target of 400 new branches, the bank opened 416 new offices between 1955 — June 1960.

The Second Branch expansion programme of the Bank and its subsidiaries covering the period 1960 —1965 provided for opening of 300 new offices. The bank actually opened 309. At the close of 1965, the Bank had 1267 offices in India. Of these, 53% were in semi-urban and rural areas with population of less than 25,000.

The rapid expansion of branches enabled the Bank to provide cheaper remittance facilities in these areas and thereby assist the development of co-operative credit. The boundaries of money-economy, once confined to the cities, where thus continually enlarged.

In the field of agricultural finance, the State Bank’s responsibilities were specifically restricted by the policy makers to indirect assistance through the cooperative movement.

The bank provided short-term and medium term loans to marketing and processing societies, subscribed to the share-capital of the Central Warehousing Corporation and also assisted in the development of Land Mortgage Banking by subscribing to the debentures issued by the Central Land Mortgage Banks or by granting advances on the security of these debentures.

As circumstances demanded a further involvement of the bank in agricultural development, the bank gave its first direct loan to an agriculturist in 1966. Total credit limits sanctioned by the State Bank to all types of co-operative institutions stood at Rs. 63 crores at the end of December, 1965.

With a view to assisting the small scale industry, the State Bank of India put into operation a Pilot Scheme at a few selected centres in 1956 which was subsequently extended to all braches. Under this scheme, the bank relaxed its usual procedures and terms of lending and began providing assistance to small industrialists at concessional rates.

The number of small-scale industries’ accounts rose from 25 in 1956 to 8234 at the end of December, 1965 while credit limits sanctioned to them rose from Rs. 11 lakhs in 1956 to Rs. 46 crores at the end of December, 1965. The Bank made full use of the Credit Guarantee Scheme operated by the Reserve Bank since 1 July, 1960.

The State Bank’s efforts to provide development finance were, thus, concentrated in two major areas —small scale industry and agriculture.

In addition, the bank, with its well-equipped machinery for foreign exchange business, also made efforts to facilitate exports and the country’s trade generally by providing:

(1) Information and packing service;

(2) Issue of traveller’s cheques;

(3) Financing import of capital goods on deferred payment basis.

The State Bank, over the 11 years since its establishment, grew out of all recognition. Apart from a sea-change in its attitude and approach to business and social responsibility, the sheer growth in size was phenomenal. By the number of branches, it was the biggest commercial bank in the country. Its deposits rose from Rs. 226 crores in 1955 to Rs. 735 crores at the end of 1965.

Deposits per branch increased from Rs. 45.5 lakhs in 1955 to Rs. 57.6 lakhs in 1965. The Bank gained in strength and prestige. The area of its service became much broader. Nevertheless, as Alak Ghosh points out, there was no sense of ease or fulfillment. This was perhaps because expectations and responsibilities outstripped even its enhanced resources.

4. Essay on the Reserve Bank of India:

The earliest attempt to set up in India a bank, with some of the characteristics of a Central Bank, can be traced as far back as 1773, when, on the recommendation of Mr. Warren Hastings, the then Governor of Bengal, a ‘General Bank for Bihar and Bengal’ was set up.

This bank, established as a private corporation, was expected, among other things, to facilitate the remittance of funds from the districts to the capital and to assist in stabilising inland exchange. It, however, proved to be a short-lived experiment.

Another attempt was made in 1807-08 when Mr. Robert Richards submitted a scheme for a bank, owned jointly by the Government and the public, more as a means to pay off the then large public debt than with the object of deriving the usual benefits of a Central Bank. The scheme was, however, rejected.

In 1836, a body of merchants, interested in the East Indies, approached the Court of Directors of the East India Company with the proposal for a “Great Banking Establishment” for British India which “would facilitate the employment in India of redundant capital of England, stabilise the monetary system, and be of great use for the receipt of revenue, and for the remittance to England of the money required for the Home charges.”

The proposal ended in smoke mainly on account of the opposition of the Bank of Bengal which expressed its willingness to take over the management of Government business and extend banking facilities in India.

Another mention of such an institution was made by Mr. James Wilson, the First Finance Member, in 1859 who referred to a proposal for establishing “upon a large-scale and with adequate capital, a National Banking establishment capable of gradually embracing the great banking operations in India and of extending its branches to the interior trading cities as opportunity might offer.”

In 1870, Mr. Ellis, a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, suggested the setting up of “one State Bank of India” under complete Government control, generally on the model of the Bank of France.

The proposal was rejected on the ground that it was not possible to induce really able and experienced men to come to India and manage such a bank. In 1884, a suggestion made for the setting up of a “Central Bank of Issue” was not persued on the plea that India possessed a sound banking and currency system.

During 1899-1901, proposals for the establishment of a Central Bank were again in the air and there was much correspondence between the Secretary of State and the Government of India. The question was hotly discussed by many of the witnesses who appeared before the Fowler Commission.

A few like Rothschild favoured the amalgamation of the Presidency Banks into a State Bank having privileges similar to those of the Bank of England but Mr. Hembro urged the establishment of ‘a strong Bank’ on the Model of the Bank of France.

The Government opposed the proposal on considerations of cost and lack of suitable persons to manage it while the secretary of State thought that the time was not right for it. The proposal was, therefore, laid aside.

The question of establishing a Central Bank was not specifically referred to the Chamberlain Commission (1913) on currency and finance. However, the Commission felt that it could not adequately deal with the subject referred to it unless it considered this question also.

Accordingly, two schemes for the establishment of a State Bank, one prepared by Lord Keynes and Sir Cable and the other prepared by Mr. L. Abrahms, were submitted to the Commission. The Commission itself gave no opinion either for or against such a bank but recommended the appointment of an expert committee to consider the question in detail.

The war time experience as bankers to the Government as also the fear of powerful foreign interests taking over the Indian banking convinced the Presidency Banks of the need of amalgamating. Accordingly, under the Imperial Bank of India Act, passed in 1920, the Imperial Bank came into existence in January, 1921.

Although it was a commercial bank, the Government entered with it into a ten year agreement whereby it was appointed sole banker to the Government. Besides, it also acted, though to a limited extent, as a banker’s Bank although it was not provided for in the Act. The central banking functions, notably, the regulation of note-issue and management of foreign exchange, continued to be performed by the Government.

The working of this central banking directly was far from satisfactory. The Hilton Young Commission, pointing out the inherent weakness of the system where the currency was controlled by the Govt. and credit by the Imperial Bank, strongly recommended the establishment of a Central Bank to be called the Reserve Bank of India.

In the Commission’s view, India needed not only a central bank but a great commercial bank also. They, therefore, recommended that the Imperial Bank, with its vast net work of branches, should attend to its essential task of providing facilities in the country.

On the recommendation of the Commission, the Government introduced in January, 1927 a bill to set up the Reserve Bank as a private share-holders’ bank though there were acute differences among leaders regarding the degree of Government control.

Mr. Jamuna Dass Mehta found ‘no charm’ in a State Bank unless it was under state control’ Sir Purshottam Dass Thakurdas and Sir Shanmukham Chetty, on the other hand, were emphatic that the Reserve Bank should be free from Government control and the influence of the legislature.

Lala Lajpat Rai wanted the Central Assembly to have a voice in the management of the bank while Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya favoured election of directors by and from the legislature. After prolonged and protracted negotiations, the joint Select Committee recommended the establishment of a wholly State Bank with 6 of the 15 directors elected by the Central and provincial legislatures.

The Government was willing to give up the shareholders principle so far as the supply of capital went but insisted that the bill would have to “live or die according to our success in finding a satisfactory directorate.” In view of the fierce opposition, the Government withdrew the bill. A fresh bill, with slight modifications, was introduced in 1928 but its fate was no better.

From 1930-31, the question of establishing a central bank received fresh impetus. The Federal Structure Sub-committee of the First Round Table Conference, held in London in 1930-31, described “as a fundamental condition of the success of the constitution that no room should be left for doubts as to the ability of India to maintain her financial stability and credit, both at home and abroad.”

The Central Banking Committee, endorsing this view, strongly recommended the establishment of a Reserve Bank “at the earliest possible date.” In response to these developments, the Government finally introduced the Reserve Bank of India Bill in the Assembly in September, 1933. It received assent of the Governor General in March, 1934, and the Bank started functioning from April, 1935.

Under the Reserve Bank Act, the Reserve Bank was set up as a private share-holders bank with a share capital of rupees 5 crores, divided into fully-paid shares of Rs. 100 each.

In order to prevent undue concentration of the share- capital in particular parts of India or in a few hands, the shares were assigned separately to each of the five regions, namely, Bombay, Delhi, Madras, Calcutta, and Rangoon, in which the country was divided. Each shareholder had one vote for every 5 shares purchased, subject to a maximum of 10 votes.

The Act provided for a Board of Directors consisting of 16 members —a Governor, two Deputy Governors appointed by the Government, four directors nominated by the Government, 8 directors elected by the share — holders, one Government official nominated by the Government but without the right to vote.

The local Board, in each of the five regions, was to consist of not more than 8 members of whom 5 were to be elected by the share holders of that region and 3 to be nominated by the Central Board.

Directors of the Central Board or members of the local boards could not be elected or nominated from among the members of the legislature. The Local Boards were purely advisory in nature, their function being to advice the Central Board on such matters as were referred to it.

The Reserve Bank was established with a view to “securing monetary stability in British India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage.”

With this aim in mind, the Reserve Bank has been exercising the functions which the central banks are expected to discharge. The monopoly of issuing notes of the denomination of rupees 2 and above is entrusted to the Issue Department of the Bank.

The Bank also acts as the fiscal agent of the central and state Governments; holds deposits from the Government but does not pay interest; gives them loans and advances and also manages the public debt. It also functions as a banker to banks, in which capacity it keeps their cash balances and gives them financial assistance whenever necessary.

It can buy and sell trade bills of different maturity provided these bills bear the signatures of a scheduled or a Provincial Cooperative Bank. The Bank can also buy and sell bills of exchange and promissory notes in the open market if this is necessary for the regulation of credit.

The other functions which the bank may discharge are the accepting of deposits without interest and the borrowing of money up to a certain limit. The Bank is also charged with the duty of maintaining the rupee- sterling ratio.

In addition, it had to establish an Agricultural credit Department, and was required to report, within three years of its establishment, upon methods of linking the indigenous banking system with joint-stock banking in the country.

Under the Act, the bank is not allowed to:

(a) Engage in trade or otherwise have a direct interest in any commercial, industrial, or other undertaking;

(b) Purchase its own shares or the shares of any other bank or company or grant loans upon the security of such shares;

(c) Advance money on mortgage of immovable property;

(d) Make unsecured loans or advances;

(e) Draw or accept bills payable otherwise than on demand and

(J) Allow interest on deposit or current account.

During the Second World War, the Reserve Bank was obliged to provide funds to the Government of India against sterling securities deposited by the British Government in a blocked account at the Bank of England.

Many, therefore, ridiculed it as being “for all practical purposes, a subordinate branch of the Bank of England.” There was a widely-shared feeling that the Reserve Bank had failed to develop as a national institution with concern for domestic stability or an interest in domestic economic development.

Therefore, as soon as the war ended, the demand for nationalisation gained momentum. In 1948, while announcing the Govt’s intention to nationalize the Reserve Bank, Sir Shanmukham Chetty, the Finance Minister, argued that:

(a) Government ownership of Central Bank was the fashion of the day and that it would ensure a greater co-ordination of the monetary, economic, and financial policies and help in speedy implementation of the Five-Year Plans;

(b) That Bank had already come under the effective control of the Government during the Second World War and that nationalisation world, therefore, mean only a dejure recognition of a defacto situation; that the affairs of the Bank were managed and controlled by a small group of capitalists who wanted to promote their own interest only.

This is proved by the fact that the value of shares held by the regions of Delhi, Calcutta, Madras, and Rangoon declined while the value of shares held by the Bombay area increased from the original rupees 1.40 crores to rupees 2.36 crores on 30.6.1946. What is more, the total number of share-holders also declined from a little over 92,000 on 1.4.1935 to 45,000 on 30.6.1947.

The proposal for nationalisation, however, met with opposition from many quarters. It was pointed out that the constitution of the Reserve Bank provided for both regulation by Government and ownership by the private sector and that such a combination was bound to work better than an institution owned by the Government only.

Fear was also expressed that nationalisation might hitch the chariot of the financial system to the wheel of political parties. It was also pointed out that after Independence, there was no difference of opinion or serious conflict between the Govt. and the Bank. The Bank had, in-fact, co-operated with the Government in carrying out her policies without giving up its own independent attitude.

The Bank had represented, so the argument ran, the interests of the nation whenever it felt that the policies of the Government were not conducive to the good of the country.

Mention was made of the Bank’s proposal to the British Government, in 1945, to make its payments in bullion or capital and consumer goods or foreign currencies and the warning it gave, in 1946, to the Government of India of the danger of following a too cheap money policy.

These objections notwithstanding, the Reserve Bank of India, (Transfer to Public Ownership) Bill was passed in 1948. The Act provided for the compulsory transfer of all privately-owned shares to the Government, compensation having been paid at the rate of rupees 118.10 per share in cash or Government promissory notes bearing interest at 3%.

The passing of the Banking Companies Act (1949) and the launching of the First Five-Year Plan imposed new and heavier responsibilities on the Reserve Bank. It had to secure a rapid development of banking facilities in the country, ensure availability of sufficient credit for an expanding economy and also channelize it into socially desirable channels.

In short, it had to work as, what Gupta regards, “as a regulator, controller, supervisor, inspector, or rather as a director of the money market” with a view to securing the economic development of the country in line with the targets and aims laid down in the plans. This necessitated changes in the constitution as well as the working of the Bank.

Under the Act of 1934, note-issue was based on the Proportional Reserve System under which the Reserve Bank was obliged to keep 40% of the value of notes issued in the form of gold bullion, gold coin or sterling securities, of which the value of gold coin and bullion was not to be less than rupees 40 crores valued at Rs. 21.38 per tola.

The remaining assets were to consist of rupee coin, Government of India rupee securities, bills of exchange and promissory notes.

Towards the end of the First Plan, two factors emerged which necessitated a change in the system. In the first place, the larger financial outlay envisaged under the Second Plan was expected to increase the money supply by 32% whereas the existing system permitted only an increase of rupees 189 crores in currency.

Even this was dependent on the balance of payments position. Secondly, the foreign exchange and gold, locked up as a backing, were desperately needed for financing development imports.

The Reserve Bank Act was accordingly amended in 1956 and 1957. The 1957 Amendment fixed the minimum foreign exchange and gold reserves to be maintained for purpose of note issue at rupees 200 crores. Of this, a minimum of rupees 115 crores had to be kept in the form of gold coin and bullion. Thus, the Proportional Reserve System was changed to the Minimum Reserve System.

One result of this change was that the Reserve Bank, in its capacity is banker to the Government, was able to make larger advances to the Government so as to enable her to meet her investment needs.

During the First plan, the financial assistance provided by the Reserve Bank to the Central and Provincial Governments, in any single year, did not amount to more than Rs. 1966 crores. During the Second plan, however, it rose to a maximum of Rs. 5034 crores and during 1961-64, to Rs. 5907 crores.

In the role of a bankers bank, the Reserve Bank regulates the operations of the commercial banks in accordance with the needs of the economy through instruments of credit control. The Reserve Bank’s advances to commercial banks amounted to Rs. 1279 crores in the First plan, 3735 crores in the Second, and Rupees 3113 crores during 1961-64.

Under the Reserve Bank Act of 1949 all scheduled banks were required to maintain a cash balance equal to 2% of time and 5% of their demand liabilities with the Reserve Bank. The distinction between time and demand was removed by the Act of 1962 which laid down a uniform 3% — could be increased up to 15% in special circumstances — of liabilities to be kept as reverse with the Reserve Bank.