In this article we will discuss about the income elasticity of demand for farm products.

The total incomes of population will also rise, on the average at a rate equal to the output increase. How will the people wish to consume their extra income? The relevant measure in this case is the income elasticity of demand, which measures the effect of increases in income on the demands for various goods.

If all goods have unit income elasticities of demand, then the proportion in which the various goods are demanded will not alter with income, and a 10% rise in income will lead to a 10% rise in the demand for every good.

Income elasticities vary considerably among goods, and that most goods tend to have different income elasticities at various levels of income. At the level of income achieved in advanced industrialized countries, many foodstuffs have very low income elasticities, and many manufactured goods have high income elasticities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Suppose that productivity expands more or less uniformly in all industries? The demands for goods with low income elasticities will be expanding slower than their supplies; excess supplies will develop, prices and profits will be depressed, and it will be necessary for resources to move out of these industries.

Exactly the reverse will happen for goods with high income elasticities demand will expand faster than supply, prices and profits will rise, and resources will move into the industries producing these goods.

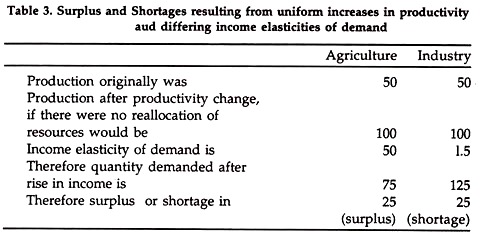

Table 3 illustrates this point.

It gives a simple numerical example of an economy dividing into an agricultural and an industrial sector. Originally, resources are divided equally between the two sectors. Productivity then doubles in both sectors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The incomes of all consumers double and the income elasticity of demand for industrial goods is higher than the income elasticity of demand for farm goods. The rise in productivity causes a surplus equal to 25% of the agricultural production, and a shortage equal to 25% of the industries production.

Thus it will be necessary for resources to move out of the agriculture and into industries. Furthermore, if the productivity increases are going on continuously, there will be a continual tendency toward excess supply of agricultural goods and excess demand for industrial goods.

In a free-market economy, this re-allocation will take place under the incentives of low prices, wages, and income in the declining sector and high prices, wages, and incomes in the expanding sector.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because there is excess supply in the agricultural sector, prices will fall and incomes of producers will fall. Because too much is being produced there will be a decline in the demand for farm labour and the other factors used in agriculture, and the earnings of these factors will be full.

At the same time, exactly the opposite tendencies will be observed in industries. Demand here is expanding faster than supply; prices will rise; incomes and profits of producers will be rising; there will be a large demand tor the factors of production used in industries, so that the price of these factors, and consequently the incomes that they earn, will be bid upward. In short industries will expand and agriculture will contract.

In a free-market society, the mechanism for a continued re-allocation of resources out of low-elasticity industries into high elasticity ones is a continued depressing tendency on prices and incomes in contracting industries, and a continued buoyant tendency on prices and incomes in expanding industries.

Now what is the effect that all this will have on the kind of govt. stabilization policy? Generally, there are two motives behind agricultural- stabilization policies: first to secure a stable level of income, and second, to provide a high level of income.

Frequently, in a wealthy community where real incomes are expanding year by year, many feel that the agricultural sector ought to share in this prosperity. Stabilization programmes often aim at providing the farmer with an income on a parity with incomes earned in the urban sector of the economy.

Our economic theory has nothing to say about the ethics of such a policy; it merely discovers its consequences. “The main problem is that a programme that succeeds in giving the rural sector a high level of income may frustrate this re-allocation mechanism and, unless some other means of reducing the size of the rural sector is found, the discrepancy between demand and supply will continue to grow until it reaches unmanageable dimensions.”

If productivity continues to increase in the rural sector while income elasticities of demand for its products are low, the excess of supply over demand will get larger and larger as time passes. If the government insists on trying to maintain agricultural prices and incomes, it will find that, as time goes by, it is necessary to purchase ever-large surpluses.

If incomes are guaranteed, there will be no monetary incentives for resources to transfer “out of the agricultural sector. Unless some other means is found to persuade resources to transfer, then a larger and larger proportion of the resources in the industry will become redundant. If, on the other hand, the government does not intervene at all, leaving the price mechanism to accomplish the resource re-allocation, it will be faced with the problem of a more or less permanently depressed sector of the community. The government may not be willing to accept all of the social consequences of leaving this sector to fend for itself.”

We should not come to the conclusion that economic proves that governments ought not to interfere with the price mechanism because the risks are too large, such a conclusion, cannot be proved; it is a judgement, which depends on a valuation of the gain and losses of such intervention.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economic Theory, “by providing some insight into the workings of the price mechanism, can be used to predict some of the consequences of such intervention and thus to point out problems that must be solved in some way or another if the intervention is to be successful. If the problem of re-allocation resources out of the rural sector is not solved, then intervention to secure high and stable levels of farm incomes will be unsuccessful over any long period of time.”