Managerial economics is the application of economic theory and methodology to decision making problems faced by public, private and not for profit institutions. Read this article to learn about the Definitions, Meaning, Concept, Scope and Theories of Managerial Economies.

The study of managerial economics offers major benefits for students and practicing managers. It enables one to learn practical applications of concepts studied in micro and macroeconomic theory.

1. Definitions of Managerial Economics:

1. “We define managerial economics as the integration of economic theory and methodology with analytical tools for applications to decision making about the allocation of scarce resource in public and private institution.” K. K. Seo & B.J. Winger

2. “Managerial economics is the application of economic theory and methodology to business administration practice. More specifically, managerial economics is the use of the tools and techniques of economic analysis to analyse and solve management problems.” J. L. Pappas & E. F. Brigham

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. “Managerial economics is the application of economic theory and methodology to decision making problems faced by public, private and not for profit institutions. In managerial economics, one attempts to extract from economic theory (particularly micro-economics) those concepts and techniques that enable the decision-maker to efficiently allocate the resources of the organization.” J. R. McGuigan & R. C. Moyer

4. “It (managerial economics) is the study of why some businesses prosper and grow, why some simply survive and why others fail at the market place and go under.” T. J. Coyne

5. “Managerial economics is concerned with the application of economic principles and methodologies to the decision making process within the firm or organisation. It seeks to establish rules and principles to facilitate the attainment of the desired economic goals of management.” Evan J. Douglas

6. “Managerial economics is the study of allocation of the limited resources available to a firm or other unit of management among the various possible activities of that unit.” W. R. Henry & W. W. Haynes

2. Meaning of Managerial Economics:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economics is concerned with the allocation of scarce resources, having alternative uses, among competing goals (or unlimited ends). Managerial economics is slightly specific in its approach. It studies the economic aspects of managerial decision making.

It provides the practicing manager with those tools and techniques which are useful in day-to-day decision making. Like traditional economics, it is concerned with choice and allocation, in a narrow sphere though, it examines how scarce resources are allocated within a firm.

Managerial economics is pragmatic. Its stress is on the real commercial world. It is concerned with those analytical tools and techniques which are useful or are likely to be so as to improve the decision making process within the firm.

Firms of different types and size arise in an economy because they have been able to organize production more efficiently than other types of institutions could. Most production takes place in business firms. In managerial economics the stress is on the process of resource allocation and decision making within the firm which is thought to be the most efficient form of organizing production.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The two terms ‘managerial’ economics and ‘business’ economics are often used interchangeably. But the scope of the former is broader than that of the latter.

While the latter deals with the decision making in profit making organizations, the former provides methods and a point of view that are also applicable in managing non-profit organizations (like hospitals) and public corporations (like the Indian Airlines Corporation).

So, in a formal sense, managerial economics is the application of economic theory and methodology to decision making problems faced by private, public and non-profit organizations. Various concepts of managerial economics can be applied to non-business or non-profit institutions.

The implementation of cost reduction programmes, the selection of more productive alternatives, the enhancement of revenues and the adoption of other measures can help to maximize the service and the social contribution of these institutions.

Governments should try to obtain the maximum benefit for tax payers in spending their revenues; government agencies can measure their efficiency through cost-benefit analysis. Hospitals often attempt to handle more patients and give better care at lower cost by applying economic techniques. Even universities can gain much by practising what they teach about managerial economics.

3. Concept of Managerial Economics:

Managerial economics is an important way of thinking about and analysing the problems that arise in both profit seeking and non-profit seeking enterprises.

Although managerial economics is an amalgam of diverse subjects, the common core is the application of the fundamental principles of economics to analyse and to help solve problems faced by organizations in a modern mixed economy.

The principles of economics and economic analysis are especially useful to managers at all levels of hierarchies in progressive business enterprises. Managerial economics emphasizes the principles of economics that underlie managerial practice. The stress is on applied economic analysis.

Immediately after the publication of Joel Dean’s first title on the subject in 1951, managerial economics has emerged as a separate discipline and been a popular subject in both under-graduate and post-graduate programmes in business administration.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Its popularity is attributable to the growing applications of economic theory in the commercial organisations as also in non-profit organizations and government companies. It seems that the subject will become more and more popular in future.

In this context one may venture to quote Joel Dean whose comment of more than four decades ago seems very important and relevant even today:

“The big gap between the problems of logic that intrigue economic theorists and the problems of policy that plague practical management needs to be bridged to give executives access to the practical contribution that economic thinking can make to top management policies.”

Before studying a particular subject two questions are likely to crop up in the minds of beginners:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. What is the subject all about?

2. Why do we study the subject at all?

These two questions have to be answered at the outset before we proceed further. We may well start with a few definitions.

4. Relation of Managerial Economics to Other Areas of Management:

It is possible to establish link of managerial economics to other areas of management. In fact, there is a relation between managerial economics and the operation of every segment in a business, and management can make use of many of the fundamental principles or theories of economics to solve everyday business problems. We normally see application of managerial economics in the following functional areas.

i. Marketing and Sales Applications:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Marketing and sales functions largely depend on an analysis of consumer demand. Marketing managers always try to evaluate the size of the market for a new or existing product.

However, the size of the market depends on a host of economic and non- economic factors which are usually incorporated in the theoretical demand function which is represented by the demand curve and the familiar ceteris paribus (other things remaining the same) assumption.

While traditional economics provides us analytical insights into concepts such as price and income elasticity of demand, managerial economics goes a step ahead in arriving at statistical estimates of elasticity’s that can be fruitfully utilized to formulate a firm’s pricing policy and to predict the size of a future market.

In fact, through the use of regression technique, managerial economics can make a positive contribution to marketing and sales functions.

The effectiveness of the marketing and sales functions is judged by a firm’s ability to charge a premium price for its product or products. The price decisions taken by marketing managers have two major aspects: consumer resistance and market competition.

In most real-life markets a firm has to reduce the price of the product to sell more. To be more specific, the marketing manager has to weigh the advantages of increased sales volume against the advantages of lower sales price (per unit). That is to say, price reduction will have two effects, of which one is favourable to the firm and the other is unfavorable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The net effect of these on total revenue depends on price elasticity of demand, a key economic concept introduced by Alfred Marshall in 1890. Managerial economics makes use of the concept of price elasticity of demand in order to numerically measure and quantify market sensitivity of demand, i.e., how sensitive consumers are to price varies among products and among markets.

Furthermore, certain fundamental principles of managerial economics can be used not only to evaluate the probable reaction of competitors to change in price, quality, service and other aspects of product, but also to quantify the effectiveness of advertising and product differentiation policies as they relate to the total demand for the product.

ii. Production and Personnel Applications:

The responsibilities of production and personnel managers differ in reality. But they have a common interest: they have the need for some reliable (though not totally perfect or accurate) estimates of the demand for the product being sold by the firm. However uncertain these sales forecasts may be, they must be translated into weekly and monthly production schedules, inventory requirements and manpower needs.

Managerial economics deals with production functions or relationships between input and output changes. Managerial economics departs from general short-term concepts of traditional economics such as law of diminishing returns and long-run concepts such as economies of scale to specific planning and budgeting issues concerning labour and material requirements.

True, a portion of this task revolves around the purely mechanical routine of estimating input-output relationships (such as the wood needed per pencil).

Another equally vital aspect of the task is to understand more subtle issues such as what happens to output and to profits per labour hour as the load factor (i.e., % utilization of existing plant capacity) increases. In the short run, the firm does not enjoy sufficient plant flexibility.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Moreover since all inputs (like labour, capital, etc.) cannot be increased proportionately in the short run, output follows the law of non-proportional return. Thus, the management has to more than double variable inputs (such as labour) in order to double output.

In some companies there is the system of productivity linked bonuses. But measurement of productivity in practice is no doubt a complex exercise, if not totally impossible. The productivity of labour and capital can be satisfactorily measured by using various techniques introduced in managerial economics. By making use of principles of managerial economics, production and personnel managers can take various decisions.

For example, they can translate average productivity, marginal productivity and production-cost functions into statistical measurement to measure efficiency of the production process and formulate wage policy and bonus plans.

Differently put, on the basis of such measurements they make resource allocation decisions. The allocation of machines and manpower among different activities or products in a multi-product firm is an obvious example of this.

The efficiency and the flexibility of the production process is perhaps the most important aspect of the performance of a firm.

For this, the managers have to understand and deal with various unknown factors such as the substitutability of capital for labour (using computers rather than part-time accountants), the tax implication of such substitution, the economic characteristics of the production process (such as diminishing return, return to scale, etc.) for pricing decisions and, of course, the cost and benefits of current inventory policies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Managerial economics can assist the practising manager in the process.

iii. Financial Applications:

Most financial decisions such as capital equipment replacement, depreciation and capital budgeting decisions have their roots in the economics of time and uncertainty.

Although traditional micro-economic theory, as presented by Marshall, is cast in rigid time frames such as the market period, short-run and long-run, in the 1970’s a separate branch of economics, viz., the economics of time was born, thanks to the pioneering work of Sir John Hicks. Business enterprises are often faced with resources allocation decisions involving very long period of time.

For example, a firm may be faced with two alternatives — whether to invest crores of rupees in new plant and equipment (with hardly any prospect of repayment for the next 5-10 years) or to spend the same amount of money on advertising. In both the cases, the economics of time becomes an important determinant of whether resources will be allocated at present or over an extended period of time.

In a like manner, the financial manager of a large corporation has to ensure that the cash flow is such that long-term financial requirements (say for a new factory) are fulfilled by long-term financial arrangements (20-year loan) and that short- term arrangements (such as a monthly line of credit) are used to meet short-term needs (such as inventory fluctuations).

If the future were known with certainty, it would be very easy to take financial decisions. However, the real life is surrounded by a penumbra of doubt. So most business decisions have to be taken under highly uncertain conditions. This requires some sort of contingency planning.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, a farmer may be required to choose between a guaranteed price achievable by selling his crop at a price fixed now in the futures market (prior to harvest) and an unknown price based on supply and demand immediately after the harvest.

Now the time value of money becomes an important factor in the decision making process. Managerial economics analyses the nature of such financial trade-offs and illustrates the relevance of the economics of time and uncertainty in various resource allocation decisions.

iv. Law-Related Applications:

Managerial economics focuses on economic institutions like the structure of markets. But legal analysis focuses on illegal actions such as collusion or restrictive trade practices such as a tie-in sales or full line forcing.

For example, to understand concentration of economic power, one must understand the Lorentz curve, to understand predatory pricing, it is necessary to understand the meaning of market power and the logic of average cost (mark up) pricing. However, these terms are not necessarily accepted by courts in the same way as they are defined in traditional economics.

In practice, the growth of a large firm, its choice of the methods of production, pricing practice and so on are all influenced by the legal environment of business. In India, there is the MRTP Act. In the USA, there are anti-trust laws. The erection of artificial barriers to entry into an industry by a large firm may be prohibited by such acts.

v. Integration of Functions:

In practice, there is often conflict among these functions. Senior management has to integrate these diverse functions so as to sub serve the overall objective of the company.

If each department or division of the company operates independently, the marketing department would most certainly choose to sell that quantity that maximized revenue, production department would choose that quantity for which cost would be minimum, the financial department would choose the least costly way of raising corporate capital and the law department would seek to minimize the degree of risk taking.

However, the pursuit of each of these objectives in isolation would not lead to the fulfilment of the overall objective of the company, i.e., profit maximization.

For example, in order to derive economies of scale (i.e., advantages of large-scale production) a firm may have to use more costly equipment’s than the ones used by its competitors. Likewise, in order to achieve production efficiency, a firm may be required to utilize more capital than would be necessary if the objective was minimizing the cost of raising capital.

Thus, whereas the managers responsible for performing each of these functions have their perception of how best to proceed in their own sphere of activity, it is necessary for senior managers, to understand these interrelationships and trade-offs. The tools of managerial economics are really useful in evaluating these issues.

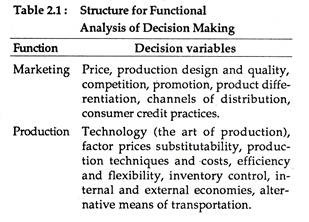

Table. 2.1 provides a broad overview of the most significant factors, internal and external, that would be taken into consideration by functional managers. Although not exhaustive, the listing does provide a convenient outline of the issues for which managerial economics can help to clarify problems facing the business organization.

5. Managerial Economics and Economic Theory (Traditional Economics):

Economics has two major branches: microeconomics and macroeconomics. The former deals with the theory of individual choice such as decisions made by a consumer or a business firm. The latter is the study of the economic system in its totality. It studies such broad aggregates as total output (GDP), national income, employment and unemployment, the general price level as also the growth of the economy.

Since managerial economics is basically concerned with economic decision making within the firm, it is more close to microeconomics than to macroeconomics. Some writers have ventured to call it applied microeconomics or price theory in the service of business executives.

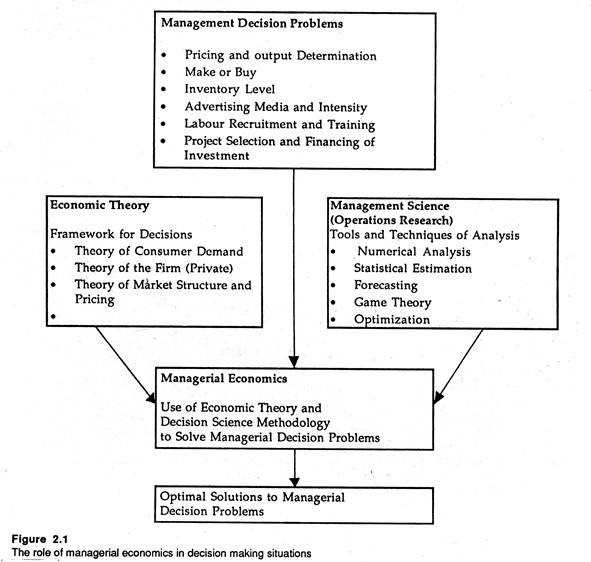

In the word of T. J. Coyne, “Managerial Economics is economics applied in decision making. It combines a broad theory with everyday practice, emphasizing the use of economic analysis in clarifying problems, in organizing and evaluating information, and in weighing alternative courses of action”. This point is illustrated in Fig. 2.1.

Managerial economics, sometimes referred to as business economics, is a relatively new area of economic analysis and has become more widespread in the past few decades. It is the application of economic theory and analysis to practices of business firms and other institutions. It deals with managerial decisions in comparing and selecting among economic alternatives.

Managerial economics is slightly broader than microeconomic theory. It also necessitates the application and integration of practices, principles, and techniques from the areas of accounting, finance, marketing, production, personnel, and other functions or disciplines associated with economics.

Because sales revenue and profits of the firm and industry are affected by the macroeconomic environment, managerial economics must relate the concept of macroeconomics to the problems of the business firm.

Because the survival, growth and prosperity of the firm are often linked to what is happening to the gross national product, the general level of employment, and the general price level, there is a need to relate the economics of the firm with the economic system.

Similarly, future sales and profits of the firm must be projected within the constraints of the growth and development of the national economy. Likewise the operations of non-profit organizations and government agencies are affected by the economic climate of a region or general business conditions of the nation.

6. Relation of Managerial Economics to Other Branches of Learning:

Managerial economics is very closely linked to microeconomic theory, macroeconomic theory, statistics, decision theory, and operations research. It draws together and relates ideas from several functional fields of business administration, including accounting, production, marketing, finance, and business policy.

i. Microeconomic Theory:

Microeconomic theory also known as the theory of firms and markets or price theory is the main source of managerial economics’ concepts and analytical tools.

Our title makes many references to such microeconomic concepts as elasticity of demand, cost, short run and long runs profits and market structures. It also makes frequent use of well- known models in price theory such as those for monopoly price, the kinked-demand theory and price discrimination.

ii. Macroeconomic Theory:

The techniques and models of forecasting are macroeconomic theory’s main contribution to managerial economics. The prospects of an individual firm often depend largely, if not entirely, on the condition of business in general. Therefore, an individual firm’s forecasts often depend heavily on general business forecasts, which make use of models derived from theory.

To actually use forecasting models in everyday business situations, close attention must be paid to details, such as inventory in the automobile industry, excess capacity in chemical manufacturing, or measurements of consumer attitudes. The manager doing the forecasting has to make a detailed demand analysis.

iii. Statistics:

Statistics is important to managerial economics in several ways:

Firstly, statistical measurements provide the basis for empirical testing of theory.

Secondly, statistical techniques provide the individual firm with methods of measuring the functional relationships vital to decision making. But statistics, vital as it is, ultimately provides only part of the input needed in decision making. Information from other sources, such as accounting and engineering, and a manager’s subjective estimates also are needed.

iv. The Theory of Decision Making:

The theory of decision making has relevance and significance to managerial economics.

Much of economic theory is based on two assumptions:

(1) Individuals and firms strive toward a single goal maximum utility for the individual and maximum profit for the firm.

(2) There is certainty or perfect knowledge in the individual’s or firm’s situation.

The decision-making theory recognizes that managers in the real world face a multiplicity of goals, and the only certainty they can count on is that each new day will bring new uncertainties.

The theoretical notion of a single optimum solution is replaced by the view that solutions must be found to balance conflicting objectives. Motivations, the relation of rewards and aspiration levels, and patterns of influence and authority all these are key factors in the theory of decision making.

The theory of decision making is concerned with how expectations are formed under conditions of uncertainty. It recognizes the costs of collecting and processing information, the problem of communication, and the need to reconcile the diverse objectives of people and organizations. It also requires that psychological and sociological influences on human behaviour be considered in the decision process.

v. Operations Research:

Operations research is closely related to managerial economics. It is concerned with model building the construction of theoretical models that aid in decision making. Economic theorists began constructing models long before the expression “model building” became fashionable. Managerial economists apply the models.

Operations research is also concerned with optimization, and economics has long dealt with the consequences of maximising profits and minimizing costs.

However, a business firm does not operate in a vacuum. It is a part of the economic system of a country. Its short-term and long-term decisions are affected by the overall (macro) environment of the country. There are certain forces such as consumer attitudes, or government policies or international competitiveness which are external to and beyond the control of an individual firm which is basically a micro-unit.

These external forces together constitute the (macro) environment of business. An individual firm can do little to affect the environment. So firms should take decisions which are consistent with the economic environment of business.

A business manager has to take both short-term and long-term decisions. In the short run he may be interested in estimating demand and cost relationships with a view to making decisions about the price to be charged for a product and the quantity of output to be produced.

Microeconomics which deals with demand theory and with the theory of cost and production is extremely helpful for making such decisions. Likewise, macroeconomics is also useful when one attempts to forecast demand for a product on the basis of the forces influencing the total economy (like GNP, aggregate consumption expenditure, aggregate investment expenditure, the rate of inflation and so on.)

A business firm has to take not only short-term decisions like production and pricing, but certain long-term decisions like investment, diversification and growth. In the long run, a business firm has to make such decisions as whether to expand production and diversification facilities, whether to develop new products and new markets, and possibly acquire other firms (mergers).

Such decisions require an act of investment or capital expenditure which will yield a return in future periods. These decisions are based on the economist’s concept of economies and diseconomies of scale and the theory of capital.

7. Normative Bias of Managerial Economics:

Traditional economics is basically descriptive in nature. But managerial economics is prescriptive. It decides whether or not a probable outcome is desirable and whether or not management should pursue courses of action leading to it.

8. Scope of Managerial Economics:

So managerial economics is concerned with the application of economic principles and methodologies to the decision-making process under uncertain conditions.

Its topics include: demand and its determinants, supply and its determinants, production functions, cost conditions, capital budgeting techniques, business and economic forecasting — short term and long-term corporate profits, and the problem of pricing in theory and practice.

Managerial economics also investigates the firm: its place in the industry, its contribution to the national economy and even its impact on international affairs.

9. Why Study Managerial Economics?

The study of managerial economics offers major benefits for students and practicing managers. It enables one to learn practical applications of concepts studied in micro and macroeconomic theory.

It is helpful in making such short term and long term decisions as: which products and services to produce? How to produce them — what inputs and production techniques to employ? How much output should there be and what prices should be charged for them? When should a capital equipment be replaced? How should limited capital be allocated? What are the best sizes and locations of new plants?

Managerial economics provides management with a strategic planning tool that can be fruitfully utilised to gain a clearer perspective of the way the world at large works, and what can be done to maintain profitability in an ever-changing environment. Much of managerial economics offers decision makers a way of thinking about changes and a framework for analysing the consequences of strategic options.

Managerial economics is primarily or largely concerned with the practical application of economic principles and theories to the following types of strategic decisions made within all types of business enterprises:

1. The selection of the product or service to be offered for sale

2. The choice of production methods and optimum combination of the substitutable resources

3. The determination of the best combination of price and quantity

4. Promotional strategy and activities (determination of optimum advertising budget)

5. The selection of plant location and distribution centres from which to sell the goods or service to consumers.

Within a business enterprise, these five types of decisions are always considered by the marketing and sales departments, the production department as also the finance and accounting department.

The major reason for studying managerial economics is that it is useful. Not only every manager but also every individual has to make economic decisions every day.

A background knowledge of the fundamental methods and principles of economic theory enables one to make wide and rational choices. Therefore, any student of managerial economics will find its study useful not only in their professional activities but also in their private lives.

Students who choose business as a career will also find economics extremely useful. It may be noted in this context that people like doctors, lawyers or other professionals are in business, too. A knowledge of economics is extremely useful in business decision making which is designed to increase the firm’s profit and enable the firm to operate more efficiently.

Moreover, economic theory is useful in helping decision makers to decide how to adopt to external changes in economic variables. For instance, increasing advertising or sales promotion expenditure or undertaking investments involve economic decisions. Therefore, a clear understanding of economic theory helps managers make the right (most profitable) decisions.

Moreover, a knowledge of economic theory is also useful to those who work for non-profit organizations like hospitals, charitable trusts, cooperative societies, etc. Certainly the goals of these organizations do not involve profit maximization, but they do involve economic efficiency.

The Ministry of Finance, for instance, may be required to allocate a fixed budget to attain the maximum benefit — in education, medical care, and so forth — permitted by the size of the budget.

Or, it may be entrusted with the responsibility of attaining a certain goal at the minimum possible cost. Managerial economics does provide the tools needed to solve these economic problems.

Economics helps not only managers of private business firms, but also managers of non-profit organizations to adapt to changes in the economic environment in the most efficient manner. So managerial economics provides efficient decision-making tools to those also who are employed in non-business operations.

i. Decision Makers’ Objectives:

In this text- we assume that executive decisions in the aggregate are directed towards achieving the organization’s primary goal. In general it is assumed that the primary goal of any organization is to maximise the benefits provided by the organisation’s operations in relation to costs. In other words, every organization attempts to make the difference between such benefits and costs as large as possible.

In non-profit organizations it is very difficult to quantify both benefits and costs. For example, we may easily count the number of graduates from a university but it is very difficult to measures the benefits they will bring to the society that subsidized the cost of their education.

In a profit-seeking organization, benefits are measured as revenue and costs expenses and money is used as the common denominator of both. Moreover, profit can be defined as the difference between benefits and costs at some given level of risk.

The difference is based on the concept of costs the economist includes opportunity cost in cost calculation and this is set against the firm’s benefits, whereas the accountant does not. But both assume that the firm attempts to maximize benefits. However, the question arises: benefits for whom? Owners or managers?

ii. Divergent Interests of Owners and Managers:

The joint stock company or the corporation is the most representative form of business organization. It is characterized by the separation of ownership from management (control).

When the ownership of a corporation is stretched over millions and millions of shareholders (who belong to diverse groups) it is unlikely that they will take an active interest in the management of the company as long as their dividends are satisfactory.

Moreover, managers may have some personal motives. Although managers enjoy discretionary power (authority) to spend the company’s funds on different projects, they are more interested in job security, large salaries, ample bonuses, stock option plans and perquisites than in maximising returns to the owners of the company.

In their path-breaking work, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (New York, Macmillan, 1932) A. Berle and G. C. Means first drew attention to the divergence of interests between owners and managers.

Later, in 1959, W.J. Baumol argued on the basis of his experience as a management consultant that maximization of sales rather than maximization of profits is a common managerial goal, and perhaps more appropriate.

Later R. M. Cyert and J. G. March argued that large corporations, or the so-called industrial giants like huge government agencies, seek to perpetuate themselves by establishing various primary and subsidiary goals that satisfy many constituents interests in the firm rather than the owners’ interest.

They identified five such goals which determine how resources are allocated within the firm, viz., sales, production, inventory, market share, and profit. With respect to the last goal, viz., profit maximization, they commented: “it makes only slightly more sense to say that the goal of a business organization is to maximize profit than to say that its goal is to maximize the salary of Sam Smith, Assistant to the Janitor.”

Whether decision-making is directed toward maximizing wealth, sales, management perquisite, or Sam Smith’s salary, there is still a need for efficient allocation of a firm’s limited resources. And this is what managerial economics is all about.

iii. Maximization of Owners’ Wealth:

There is no denying the fact that the primary goal of a business firm is profit maximization. However, this is not the same thing as maximizing owners’ wealth unless risk is taken into consideration. This explains why profit is defined as the difference between benefits and costs at some given level of risk. If risk is assumed to remain constant, profit maximization amounts to maximizing owners’ wealth.

iv. Social Constraints:

The goal of achieving maximum profit is often tempered by the social responsibilities of the firm. In general most of these are imposed by the government, but in some cases the firm’s management assumes social responsibilities on its own initiative. For instance, the Tata group spends a huge amount of money on education and research. They also provide scholarships to students intending to study abroad.

The pertinent question here is how far a firm can be expected to go ahead with more social responsibility programme whose costs far exceed the benefits which they bring. Moreover, unless all firms participate in such socially responsible programmes, those that do will bear an inordinate share of the costs. This will undoubtedly lead to a fall of earnings and shareholder wealth, at least in the short run.

It may be noted that various institutional arrangements in a free market system (which relies on supply and demand to allocate resources and commodities) affect the various functional divisions of a business (say, the marketing and production departments).

Managerial economics is basically concerned with how individual economic units behave, make decisions, and respond to changes in the external (macro) environment of business. In other words, economic theories and models focus on the individual firm, or industry, consumer or group of consumers, but they ignore social issues of the goals or society or that of the public at large.

10. Corporate Managerial Economic Decisions:

There are at least eight different types of decisions with which business economists are likely to be associated in a typical company.

These are the following:

i. Demand Forecasting:

With the advent of large economy-wide econometric forecasting, demand forecasting has become an increasingly important function of business economists. Most large and medium-sized corporations in the USA have some sort of econometric forecasting model for predicting demand for a variety of goods and raw materials whose sales are linked to some national econometric model and data base.

In some companies, it is the task of business economists to produce such forecasts. In other companies business economists may collaborate with outside consultants who generate the demand forecasts.

Alternatively, the business economist may serve as an in-house consultant to those in the company who are actually carrying out the forecasting exercise.

ii. Pricing and Competitive Strategy:

Pricing decisions are often within the purview of company economists. However, pricing problems are merely a subject of a broader class of economic problem faced by a company: competitive analysis.

Competitive analysis not only requires anticipation of the response of competitors to the company’s pricing, advertising and marketing (product market) strategies but also an evaluation of the impact of the company’s sales turnover (or market share) on alternative marketing strategies employed by competitors.

Rational pricing and competitive marketing decisions are based on considerable knowledge of specific product markets and industry behaviour on the part of the business economist.

iii. Cost Analysis:

Information on cost is required for decision making purposes. This requires thorough cost analysis. Various cost analysis exercises are carried out by the cost accountants and industrial engineers.

However, in some situations, the production process is so complex that they necessitate the assistance of a business economist whose task it is to provide an appropriate conceptual framework for defining costs. Business economists are also expected to participate in business cost-benefit analysis. Economists also assist corporate planners in formulating realistic models of production operations.

iv. Supply Forecasting:

In a world of demising resources, supply forecasting is no less important than demand forecasting. The oil price hike of the 1970s and shortage of other raw materials have increased the importance of forecasting of factor supplies and prices.

Supply forecasting is not a micro exercise, i.e., an exercise that can be carried out at the micro level. Such forecasting is to be based on national and international developments — both in economics and politics.

v. Resource Allocation:

Economics is a science of choice making. It deals with the allocation of scarce resources among competing alternatives. If there is scarcity but no alternatives, choice making is impossible and the problem is not economic in nature; if there are alternatives but no scarcity (goods or resources are free) economics is not required.

Resource allocation is important regardless of the economic and political system of a country. Products must be produced and resources must be allocated. Economics is often defined in terms of the problem: “How do we allocate scarce resources subject to a set of constraints?”

The business economist is concerned with how scarce resources are (or ought to be) allocated within an enterprise. Linear programming is a technique of ensuring optimum allocation of scarce resources within an enterprise.

vi. Government Regulation:

There are endless implications of government regulations on the business firm and at times the legal environment of business is as important as the economic environment. So, it is necessary to examine law-related applications of economic principles.

vii. Capital Investment Analysis:

Just as production decision is a short-term decision, capital investment decision is a long-term decision. Investment refers to expenditure on capital goods. Such expenditure may involve lakhs or crores of rupees.

Since resources are limited, companies have to allocate scarce resources among different activities or- branches of production. The business economist plays an important role in capital budgeting decision which is concerned with allocation of capital expenditure over time.

viii. Management of Public Sector Enterprises:

Managerial economics can also be applied to the decision making process of non-profit seeking and public sector enterprises. Economists in various government departments and public sector organizations are also concerned with project evaluation and cost-benefit analysis.

In recent years, many large firms have turned to corporate managerial economists for help in making decisions which are critical to “the running of the business”.

America’s famous magazine Business Week (Feb. 13, 1978) summed up the role of the managerial economist as follows:

“…… companies across the country are now demanding less of the old-style corporate economist who churned out sweeping economic forecasts, which often were swept into the waste basket, and are turning instead to the new-style economist who can play his skills in such fields as econometrics and industrial economics to help shape company policy. Indeed, an increasing number of them have joined the team of top-level executives who map business strategy.”

The managers of a firm are mainly responsible for making most of the economic decisions such as the type of product produced, its price, the production technology utilized, and the financing of production — which will ultimately determine the performance of the company, i.e., its profits and losses.

A study of managerial economics enables the practicing manager (or the decision maker) to learn the economic principles which are relevant to decision-making in all of the areas of firm management.

Likewise, an understanding of these principles will enable M.B.A. students or tomorrow’s managers to know which questions to ask and thus what data are needed, as well as what decision to make once the data are obtained, in order to assist the firm in maximizing profits.

Even if one does not eventually become a managerial economist, he (she) can hope that at least he will be able to communicate with economists properly and recognize when help from them can prove useful for problem solving.

In some parts of this title we shall assume that the goal of a firm is profit maximization, or making the greatest possible total profit. However, even when a firm has more complex objectives, managers benefit by knowing the difference between an efficient or profit-maximizing strategy, and one which sacrifices some efficiency or profit in order to achieve other goals.

11. The Managerial Economic Theory of the Firm:

The fundamental analytical framework for the study of managerial economics is provided by the economic theory of the firm, which consists of three basic elements.

1. Goals,

2. Information, and

3. Decisions.

i. Goals:

A business firm has to satisfy the goals of any one of the following groups of individuals:

1. Consumers

2. Employees

3. Society

4. Shareholders

5. Managers.

In general it is assumed that in most firms share holders and managers have a common goal profit-maximization. On the contrary, if the firm’s objectives are formulated by its consumers, one possible goal might be the minimization of the cost of producing a particular collection of goods and services.

Alternatively, the consumers might be interested in increasing the firm’s output of a useful commodity while holding production costs fixed.

In large corporations shareholders are interested in profit maximization but managers (being salaried people) are more interested in their own security and well-being. So there is a conflict between profit-maximization and security maximization.

In this title we shall define the problem of the firm in terms of a decision problem for the managers of the firm. We are interested in exploring how managers should make decisions (normative economics) in order to achieve particular goals.

To the extent that these normative models correspond to the behaviour of firms in the real commercial world, attempt will be made to explain how managers of firms actually make decisions (positive economics).

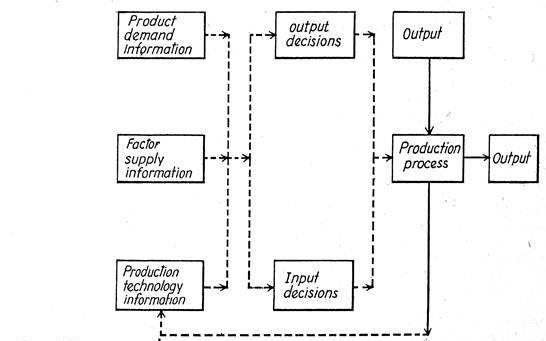

Figure 2.2

A flow chart of the decision process of a firm

For the purpose of analysis we often classify the goals of managers as:

(1) Profit,

(2) Functional, and

(3) Personal.

The profit-maximization goal (hypothesis) is based on the assumption that managers either voluntarily or of necessity behave in a manner consistent with the interests of shareholders (because the amount of dividend that can be distributed by a firm depends on the amount of profit made by it).

To the extent that professional managers are motivated to relate their behaviour to the goals of shareholders, profit maximization can be treated as the operational goal of the firm. In reality, there is not only evidence of conflict of interests of managers and shareholders, but also that functional and personal goals are more important than profit-maximization.

Functional goals, on the contrary, relate to some sub-system of the firm rather than the firm in its entirety.

Three possible functional goals are:

(1) Production,

(2) Sales and marketing and

(3) Financial.

The goals of a production manager may be:

(1) Completion of delivery schedule on time,

(2) Minimization of the sum of capital investment expenditures, operating costs and in-process inventory costs and

(3) Achievement of an even distribution of work-loads among all production facilities and a target production rate.

The objective of the sales and marketing managers may be to maximize sales revenue, not profit. This point has been made by Professor W. J. Baumol. The objective of sales maximization implies committing the firm to completely unrealistic production and time orders. Moreover, the sales manager might opt for large inventories of finished goods to ensure prompt delivery and excellent services to customers.

Likewise, giving necessary financial support to other departments is the headache of the financial manager. He (she) has always to worry about whether there is enough cash to support the company’s production and marketing activities.

Finally, the Chief Executive Officer has to do the best of a bad job of balancing the conflicting goals of production, sales and financial managers. It is because the CEO has to worry about the overall profitability of an enterprise.

The personal goals would include such things as salary, job security, status, prestige, professional excellence and job satisfaction.

Yet, at the end, the fact remains that no firm would exist for long unless it makes it makes profit. So, profit maximization is the primary goal and others are subsidiary goals.

ii. Information:

Business decision making (including forecasting) is based on three types of information: product- demand information, factor-supply information and production-technology information.

iii. Decisions:

On the basis of the above goals and information, the firm has to make two sets of decisions: output decision and input-decisions. It is because the sales plan of the business firm is followed by its purchase plan. The output decisions are concerned with which product to produce and in what quantities.

The input decisions are concerned with which factors of production to buy and hire and in what quantities. The following flow chart illustrates the major decisions of a firm. The broken lines indicate the flow (direction) of information and the solid line represents flows of factors (inputs) and final goods (end products).

Two primary tasks of managers are making decisions and processing information. In reality they are inseparable. In order to make rational decisions, managers must be able to obtain, process, and use information. It is the task of economic theory to help managers know what information should be obtained, how to process it and finally, how to use it.

The task of organizing and processing necessary information in conjunction with economic theory may assume two different forms. The first involves a specific decision that must be made by the manager. The second involves utilizing readily available information to carry out a course of action for furthering the goals o£ the organization.

One can give various examples of the first form of decisions that managers might have to make such as:

(1) Whether or not to close down a branch of the firm that has recently become unprofitable (the GKW has recently closed down one of its branches);

(2) Whether to keep a restaurant open for more hours a day;

(3) How a government agency or department can be reorganized so as to make it more efficient,

(4) How a hospital can treat more patients, without a decrease in patient care, and

(5) Whether to install an in-house computer rather than pay for outside computing services.

These and various other diverse managerial decisions require the use of the fundamental principles of economics. In fact, economic theory serves a very important purpose. It indicates that information will be useful in solving business problems and in enabling firms to operate more efficiently.

In other words, traditional economic theory enables business decision makers to know what information is necessary to make the decision, and how to process and use that information.

After gathering the necessary information from all possible sources, managers must analyse this information and use it along with theoretical statistical methods and techniques available to make the best decision possible under the circumstances.

Economic theory is useful in several general forms of managerial decision making as well. This type of decision making involves using readily available information to carry out a course of action that furthers the goals of the organization.

Business managers obtain useful information everyday from various sources such as the R.B.I. Bulletin, business magazine such as the Business Environment, Economic Scene, Business India, financial dailies like The Economic Times, The Financial Express, television, newsletters from chambers of commerce and trade associations and conversations with others.

Successful managers know how to pick out and utilize the relevant information from the vast amount of information they receive for decision making purposes. In other words, they know how to make a proper evaluation of such information and act on it to serve the purpose(s) of the organization better.

However, it is necessary for a manager to know the goals of the organization. It may be recalled that managerial economics is useful not only to managers in profit making firms but also to managers in government and in non-profit organizations. The primary goal of a manufacturing firm is to maximize its total profit.

On the contrary, the primary goal of a non-profit organization like a foundation would be to fulfil a mission or to further some cause.

For instance, the goal or the mission of a hospital would be to treat as many patients as possible, subject to the condition that its standard of performance (quality of medical care) does not fall. The goal of a university would be to educate as many students as possible subject to certain acceptable standards.

12. Purpose of Managerial Economic Theory:

Economic theory is nothing but a way of thinking about problems, a logical system for processing and utilizing information.

As S. C. Maurice and C. W. Smithson have opined, “theory is designed to apply to the real world; it allows us to gain insights into problems that would be impossible to solve without a theoretical structure. We can make predictions from theory that will hold in the real world even though the theoretical structure abstracts from many actual characteristics of the world.”

Economic theory enables us to make sense out of confusion. The real world is no doubt complicated. There are an infinite number of variables which keep on changing continuously. In fact, theory enables us to discriminate between relevant and irrelevant variables. The theoretical structure permits us to concentrate on a few important forces and ignore others.

The ability to select important factors (issues) and ignore insignificant ones enables managers to tackle the problems they are faced with. This, in its turn, helps managers to know what information is useful in making decisions and what is not.

To recall, a major role of a manager is obtaining and processing information. It is the task of economic theory to give a clear indication to a manager what information is relevant to the decision at hand and how to use that information.

i. Models and Sub-Optimization:

The real commercial world is no doubt complex. A firm’s decisions hinge on a great many technological and social factors — so many that only a few characteristics of the environment can actually be considered as part of the decision making process.

Moreover, these selected characteristics can be known only approximately. Managers, therefore, plan with models and simplifications and settle for local improvement of results, not global optimization.

Models are simply structures involving relationships among concepts. Since the concepts are of Managerial Economics ten represented as symbols, their relationships can be expressed in mathematical form. That permits quick determination of the expected results of changes in controllable variables.

Using the demand equation or model of demand, a car manufacturer, for instance, could quickly estimate the effects on sales of changes in price or advertising expenditure. Models are no doubt abstractions from reality.

But their virtue lies in the fact that they allow the analyst to understand, explain and predict the future course of events. However, the real purpose of a model is to represent characteristics of a real system in a way that is simple enough to understand and manipulate.

Any model or theory must necessarily simplify. In managerial economics, a paradox is encountered. Managerial economics often assumes a desire to optimize a given objective such as profit. However, in reality, very few managers actually seek the greatest attainment of a single goal. They settle for partial achievement of various goals.

They recognize that pursuing only one objective may mean partial sacrifice of another. Even if a manager could specify a single goal, he or she could not achieve the optimum in the true sense. Company economists must adopt a mixed attitude toward such assumptions. The assumptions are often simplified to make an allowance for failure to fully achieve the optimum.

Operations researchers use the term sub optimization for describing the process of decision making by abstraction from the total complexity of reality and from the wide variety of goals.

They construct models that partly reflect the complexity of the real world and face up to the bounds of human rationality. The results may be imperfect but superior to decisions based on crude rules of thumb or simple repetitions of past decisions.

ii. The Environment of the Firm:

One of the goals of this title is to get the reader to look at the world of microeconomics both through the looking glass of an economist and from the perspective of a business person.

While this title is largely devoted to the task of helping the reader (or the practicing manager) to master the theoretical insights that microeconomics can provide to managers of modern business firms, it is in the Tightness of things first to acclimatize on self to the business setting — that is, the reader must acquaint himself or herself with the economic realities of the business environment.

True enough, if there is a single common thereat that permeates the business person’s view of the real commercial world, it is the necessity to adapt to change. In a market economy (as opposed to a centrally managed economy), the success in business is measured by how businesses anticipate and respond to the changing nature of the market place.

Today’s business world is dynamic in nature. It is characterized by changes in tastes and preference of buyers, migration of people from rural to urban areas, technological progress and so on. In such a dynamic environment, a business firm has to take various strategic decisions and this, in turn, necessitates the integration of managerial economics into the business environment.

These factors include various factors which determine consumer demand for its product, such as consumer income; the price of the commodity under consideration; prices of competitive and complementary goods; and advertising (sales effort) of competing products; population growth; immigration of people from rural to urban areas; consumer tastes and preferences and a host of other factors.

However, what is specially relevant for the pricing decision of the firms is the type of product market in which it operates. The stress will primarily be on the number of firms in a given market and the corresponding profit maximization hypothesis will be examined first in the context of pure competition and then in the context of pure monopoly.

We shall also discuss in due course special pricing and production decisions such as those associated with the internal transfer of a product from one division of a firm to another, jointly produced products, and price discrimination (differential pricing) among different groups of buyers.

The firm’s cost of production and distribution are also affected by another environmental factor, viz., the current state of technology, which helps to determine the opportunities for economies of scale in production.

However, the firm’s costs are affected by internal factors such as fixity of some of its inputs (e.g. land or capital goods) in the short- run as also by the input market structures with which the firm must deal.

The environmental factors or environmental elements in the decision making process assume greater complexity when a firm’s management is contemplating new investments.

For example, some of the alternative capital investment projects may involve lines (methods of production) which are unknown to management. Moreover, the longer time period relevant to this type of decision brings forth the possibility that many more variables may change in a way that is unexpected in a short-run analysis of current operations.

iii. The Scope of the Text:

This book is concerned with the economic decisions of a firm as also the manager’s part in the process. This has been the traditional subject matter of microeconomics. However, the differences between managerial economics and traditional microeconomics lies primarily in the emphasis of the former on the practical application of well-known principles to economic problems of managers.

The present title is perhaps the most comprehensive of all because it examines various aspects, topics and examples of managerial economics.

Some of the new subject to be covered include various cost concepts, valuation of assets, labour and manpower planning, cost-benefit analysis, economic evaluation of projects, corporate planning and strategy, mathematical programming and operations research (management science).

Since managerial economics is goal-oriented, an attempt has been made in this title to discuss those strategies and choices which are vital to the firm’s survival and growth.

We have already noted that there is really no substantial difference between ‘traditional economic theory’ and the theories used in managerial economics. The differences lies entirely in the way the theories are applied.

The primary emphasis in microeconomics or price theory is on individual behaviour — how individual decisions of buyers and sellers lead (or often fail to lead) to efficient allocation of goods and factors among consumers and private business firms, and, in the process, maximization of society’s welfare (i.e., the maximization of the sum total of benefits to all members of society).

Similarly, microeconomic theory is applied to discover the effects of the actions of private or governmental decisions makers on the economy. There is hardly any concern with the way decisions should be made, the focus is upon the effects (cost and benefits) of the decisions on society as a whole.

On the contrary, in managerial economics, which is also called applied micro-economics (or price theory at the service of business executives), the focus is on how decisions should be made by management in order to achieve the firm’s profit maximization goals.

Whether such decisions or their results are beneficial from society’s point of view is not of any concern to managers. Although welfare consequences of managerial decisions are important, they are of secondary consideration in managerial economics.

However, in spite of the difference in emphasis, a primary concern in a course of managerial economics is with learning the fundamentals of micro- economic theory — the basic tools used by economists.

Although the theoretical methods of traditional microeconomics appear to be relatively simple, they are often made use of by ‘real-world’ decision makers. In other words, a major portion of the economic theory to be used in this text can be fruitfully utilized in a wide variety of decision-making situations.

This text is designed to help the student learn basic economic theory and to allow him to practice business using economics in order to become a competent professional decision maker and manager. By reading this text the student will learn to use the basic theoretical tools, the fundamental methods of analysis and the basic approaches to problem solving used by professional economists and business analysts.

![clip_image006[4] clip_image006[4]](https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/clip_image0064_thumb.jpg)