Get the answer of: Is there any Trade-Off between Inflation and Unemployment?

One point of contrast between demand inflation and supply or cost-push inflation is that unlike the former, the latter takes place before full employment is reached. Since cost-push inflation is largely caused by rising wages, supply inflation can be controlled by maintaining stability of wage rate.

A restrictive policy can prevent wage-inflation provided it creates enough unemployment to prevent such wage increases that are not related to increase in labour productivity. Thus the economy may be forced to pay a price in the form of unemployment for having price stability.

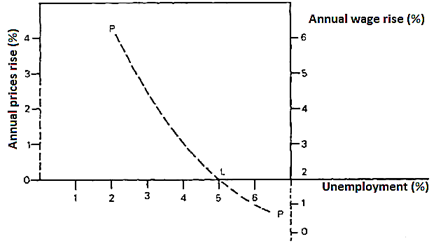

Since late ’50s some economist have paid attention on the relationship between the rate of wage increase (Δw/w) and the percentage of labour unemployed. The analysis is based upon Phillip’s curve named after A.W. Phillips. In his empirical study (1958), Phillips found an inverse relationship between the two variables. So Phillips curve has a negative slope from left to right, as Fig. 2 shows.

On the horizontal axis measures percentage of unemployment and on vertical axis, the percentage change in money wages. PP is the Philip’s curve denoting that wage rates tended to rise when unemployment rates were low and vice-versa.

As price level is closely related to the wage cost, from Phillip’s curve it is easy to draw an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment rate. If we desire to have a lower rate of inflation we must have to accept a higher rate of unemployment.

The inverse relationship between the rate of wage increase and that of unemployment can be explained by the fact that at a very low level of unemployment general excess demand will persist, and this will cause a demand-pull on wages, so that wage rates will be high.

On the other hand when unemployment increases, the role of wage increase will tend to diminish as labour union’s bargaining capacity becomes weak and at the same time, employer’s resistance becomes stronger. As Samuelson has remarked, “The softer the job market, the weaker are wage pressures.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Phillips Curve thus shows that full employment and price stability are not mutually compatible as goals of economic policy. The policy measures used by the government for creating jobs and real income tends to inflationary price rise and anti-inflation measures tend to create unemployment, putting the government on the horns of a dilemma.

The Phillip’s curve is also useful in explaining stagflation, a new kind of inflation to be found in developing economics. Generally, an economy suffering from high unemployment and unused productive capacity in different sectors with massive inflation is said to be in the midst of Stagflation. The economy simultaneously experiences the two economic evils — inflation and unemployment. And the Phillips hypothesis indicate alternative combinations of inflation and unemployment.

Limitations:

It has been argued that all rise in wages are not necessarily inflationary. If labour productivity increases along with wage rise, it need not be inflationary. It is only such increase in money wage which is not related to productivity gain that causes inflation. The horizontal line WW shows the percentage increase in labour productivity and therefore this much increase in wages is non-inflationary.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Milton Friedman has said that in every economy there is a “natural rate of unemployment” that is unaffected by and incapable of affecting wages and hence prices. This level of unemployment is, therefore, compatible with price stability.

And this level of unemployment is said to be socially desirable. If the government attempted to reduce unemployment below the “natural rate” it can do so but prices will start rising as labour market tightens. It would create a new Philips Curve. The matter may be explained graphically.

At point L the economy has a natural rate of unemployment (say 5%) with no inflation. Suppose public policies reduce unemployment below this level (e.g., 3%). Now the economy will face the problem of stagflation — co-existence of inflation and unemployment.