Read this article to learn about the linkage between employment and and output level in an economy.

It is clear that full employment has become the major objective almost in all countries. We have also seen that there exists a close link between employment level and the output level.

In other words, the trio income, output and employment (Y, O, E) move or vary more or less in the same direction and constitute the main indicators of an economy’s overall performance.

The link between real income (E) and the employment (Y) is important for economic analysis because it contains a number of simple but fundamental economic relationship.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At any time there exists for the economy as a whole a given productive capacity, that is, a potential for the production of goods and services. This productive capacity varies in the long-run as also in the short-run. In the short run, however, the variation is small and negligible (so that capacity may be taken as stable). Nevertheless, all economies have an upper limit to the amount of goods and services that can be produced and this upper limit constitutes what is called—economy’s ‘short-run’ maximum capacity to produce.

Over time, when this capacity to produce changes, we give it the name of ‘dynamic economy’, in which the capacity to produce expands continuously. The determination of the factors that determine the productive capacity is a very difficult task. It depends in simple sense on the quantity and quality of available resources in the economy, skill arid efficiency with which these resources are combined called technique or technology. Technology implies the overall level of effectiveness attained in the economy in combining resources together in the productive process.

Symbolically, it may be expressed as follows:

Q = ƒ(N: K: R: T)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

where Q—is the productive capacity of the economy; A”—the labour force; R’—stock of known and useful natural resources; K’—stock of capital or man-made means of production; T— the level of technology prevailing in the economy. This equation shows that the productive capacity of the economy is a function of the basic factors mentioned in this equation like quantity of labour, stock of capital, natural resources and level of technology.

This equation does not denote the exact proportions in which these determinants of capacity are combined; it merely shows that productive capacity is a function of or depends on these factors. Let us note that technology in the above equation is not a stock—as are labour, capital and natural resources—that is why, it is separated from other variables by a semicolon (technically, it is a ‘shift parameter’ which when combined with other quantities of the determinants determines the final capacity).

Again, just as the economy’s productive capacity (Q) depends upon the quantity of available resources; the actual level of output (O) is determined by the extent to which these resources are being used or the proportion in which these resources are being combined. In other words, output is the result of the utilization of the productive capacity.

In economics the physical relationship that exists between the input of resources and the output of goods and services in any given period of time is called the ‘production function’. In other words, a production function shows a functional relationship between the quantity of input and the quantity of output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Symbolically it is shown as below:

Y = ƒ(N’, R’ K’ T)

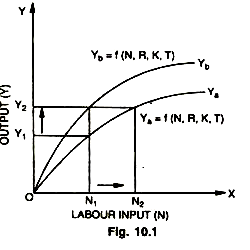

It means that given the stock of natural resources, capital and the level of technology—output (Y) is determined by labour input (N), which shows the level of employment. This production function is as shown in Fig. 10.1.

In this figure labour input is measured along OX and output along OY. The output curve will finally level off because of diminishing marginal productivity. Curve Ya shows that an increase in income from Y1 to Y2 results when employment increases from N1 to N2. But the income may increase with no change in employment if the production curve itself shifts Ya to Yb. This may happen due to change in capital stock, natural resources, change in technology or a change in the combination of these determinants.

Although we are trying to understand and analyse the salient features of the classical theory of employment yet it might be interesting to know that it is a misnomer to say that there is anything like classical theory of employment because none of the writing of leading classical economists contains an explicit account of the determinants of such a theory of employment.

Nevertheless, there exists in the literature of classical economics certain basic ideas relating to employment, which, when put together, constitute a logical and coherent explanation of how employment is determined. Since the major objective of Keynes’ ‘General Theory’ was to refute the classical theory, as such, it became necessary to have a clear conception of the classical theory of employment. In brief, such a classical theory of employment consists of three basic propositions.

First, there is a theory of demand for and supply of labour derived from the economies of individual firm and generalized’ to apply to the economy as a whole. Second, there is a level of aggregate demand for the economy as a whole and it is never deficient (on account of Say’s Law). Third, there is a theory of general level of prices, in which the general price level changes in proportion to the quantity of money and money has no role to play or influence relative prices. A detailed analysis of the classical theory of employment must depend upon a detailed analysis of these three ‘building blocks’ of the classical system.