Read this article to learn about the eight major grounds of classical employment theory.

1. Money Wages No Way to Reduce Real Wages:

According to Keynes we cannot reduce real wages by reducing money wages, however hard we may try, as this would lead to a reduction in aggregate demand, prices and profits.

Moreover, workers are under what Keynes calls “Money Illusion”, i.e. they are very sensitive to changes in money wages and are more concerned with given money wages than with given real wages.

As Keynes himself says, “Whilst workers will usually resist a reduction of money wages, it is not their practice to withdraw their labour whenever there is a rise in the price of wage goods. Keynes believed labour to be subject to money illusion. He felt workers were far more conscious of changes in money wage rates than changes in price level and that they would regard an increase in money wages as an increase in real wages, even if prices rose in proportion to wage increase.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This implies that if money wages remained unchanged, an increase in the price level would not be noticed by workers, who would, wages therefore, offer the same supply of labour even though real wages had fallen. It is no doubt true that wage bargains are made in terms of money and that the real wages acceptable to labour are not altogether independent of what the corresponding money-wage happen to be. Nevertheless, it is money-wage thus arrived at which is held to determine the real wage.

The classical theory assumes that it is always open to labour to reduce its real wage by accepting a reduction in its money wage. But this is not so. The traditional theory maintains that the wage bargains between the entrepreneurs and the workers determine the real wage, but it may be noted that only money wages are so determined and not the real wages.

Thus, Keynes rejected the classical theory of unemployment, which, in his view, asserted that:

(1) Wage bargains between workers and employers determine real wages, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(2) The level of (real) wages thus arrived at determines the amount of employment.

He agreed—basically on the assumption of diminishing returns—that an increase in employment can only occur to the accompaniment of a decline in the rate of real wages. His basic difference with the classical theory lay rather in his argument that there was no expedient which later as a whole can reduce its real wage to a given Fig. 10.7 by making revised money bargains with the entrepreneurs.

2. No Full Employment (Under-Employment Equilibrium):

According to Keynes, the tacit assumption of full employment by the classicals is not wholly warranted by actual facts, as there always exists some unemployment in the economy based upon the philosophy of laissez-faire capitalism. Booms and depressions are common features of capitalist economies and investments are not only inadequate but also often fluctuate. In such economies less than full employment is the rule, and full employment equilibrium only an exception.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, Keynes felt that under-employment equilibrium (equilibrium at less than full employment) is the normal situation in such economies. Keynes, thus, gave a rude shock to the classicals by challenging their most important assumption regarding the existence of lull employment. Having presumed the full employment of resources, the only problem with the classicals was how to allocate the given quantity of resources in an optimum manner between firms and industries; to them, there was no wastage of the resources as these were assumed to be fully employed.

Keynes, however, denounced this assumption on the plea that there is a colossal waste of resources in a free enterprise economy on account of the frequent fluctuations in output and employment in the economy as a whole. Besides, unemployment results in the wastage of time, money and energy. According to S.E. Harris, “To Keynes the waste of economic resources through unemployment seemed non-sensical and suicidal. He concentrated more of his energies on the solution of this problem than any other, and he had considerable success.”

In the ‘General Theory’, Keynes explained the manner in which underemployment equilibrium was reached and stressed its importance. This is his major contribution and at the same times the target of innumerable criticisms. The classical assumption of full employment in the economy is based on Say’s Law of Markets, according to which whatever is produced is automatically consumed. Keynes, however, held that level of employment at a time is determined by effective demand. Effective demand is that point where the ADF curve is cut by the ASF curve.

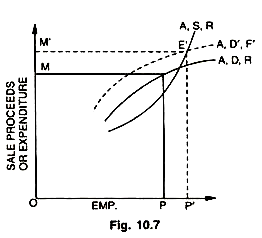

In the Fig. 10.7, E is such a point. At this point, the economy is in equilibrium because- Y = C = I, i.e., aggregate demand is equal to aggregate supply. At this point, OP level of employment is generated. According to Keynes, this is by no means a full employment equilibrium because out of the total labour force of OP’, only OP men are employed and PP’ are unemployed. In order to employ these men aggregate demand must rise as indicated by ADT’ curve which is interested by the ASF curve at E’ which is the point of employment equilibrium.

Thus, we can easily see that the effective demand in the economy (expenditure) may or may not be enough to generate a situation of full employment ; for example, in the above diagram unless the monetary expenditures rise from OM to OM’, the point of lull employment equilibrium (E) cannot be attained. It is, therefore, clear that the unique value of effective demand (equilibrium value, i.e., Y = C + I) is established at the point of intersection of the aggregate demand schedule and the aggregate supply schedule.

There is, however, no reason to believe that the point of effective demand thus attained will necessarily correspond to full employment. It may or may not be a point of full employment equilibrium as the equilibrium in the economic system may be attained at less than full employment level. Full employment equilibrium in the economy will be established only when investment demand happens to fill the gap between the aggregate supply price corresponding to full employment and the amount which the people as consumers choose to spend on consumption out of the income at full employment.

3. Say’s Law Ineffective:

Say’s Law of Markets, which was the core of classical theory became the subject matter of special attack from Keynes. Keynes particularly condemned Say’s Law for its exhortation that ‘supply’ creates its own demand and that there is no general over-production and unemployment. According to Keynes, income is not automatically spent at a rate which will keep all the factors of production employed.

Unemployment, according to Keynes, is on account of the failure to spend current income on consumption and investment goods. In a free enterprise economy, supply does not automatically create enough demand within the economy. Classical theory based on Say’s Law is no good and is not warranted by facts.

The actual state in a free enterprise economy is a fluctuating level of income, output and employment which depends upon effective demand, the deficiency of which causes unemployment and the excess of which causes inflation. Keynes never felt convinced by the Pigovian formulation of Say’s Law that wage cuts can cure unemployment. Prof. Pigou argued that wages should be cut to increase employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to him this was possible because under thorough going competition in the labour market, workers will bid wages down till they are all employed. Keynes, however, did not agree with his thesis. Wage reductions, according to Keynes, were no remedy to reduce unemployment as this will also reduce the general purchasing power of the workers thereby leading to a decline in the effective demand. Keynes also felt that under modern conditions it is not at all easy to resort to wage cuts on account of the strong growth of trade unions resulting in more collective bargaining.

4. Neglecting Role of Money:

Keynes linked the theory of money to general theory. Money, in Keynesian system is the link between the present and the future. Denouncing the classical theory of value and distribution as partial theory. Keynes remarked that treatises with little or no attention paid to money are not likely to be popular unless they deal with income formation also. Keynes integrated the theory of employment and money with the theory of income.

He took strong exception to the veil attitude of classical and denied that money is an illusion. He brought forth the importance of precautionary and speculative motive for money. Money is no more merely an accounting device. Suggesting that inflation (increase in money supply) in the ordinary sense was no longer heinous affair that conservative mood made it out to be, he insisted that a rise in prices could be a pleasant and respectable experience. In other words, the influence of money on income, output and employment was duly recognized.

Keynes was basically a monetary economist and when he moved from the narrower field of monetary theory to the broader field of general theory, he took money along with him and gave it utmost importance in the determination of employment. Out of the medium of exchange, unit of account and store of value functions of money, the last one is most important as money is the simplest form in which to store wealth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Prof. D. Dillard, “Owners of money have a type security which owners of other kinds of wealth do not enjoy.” In a dynamic and uncertain world, people prefer to own money to owning income-yielding wealth (like bonds, securities, etc.). The rate of interest is the reward for parting with control over money in its liquid form, on which depends the investment, which in turn effects employment.

It is in this way that money comes to occupy a central position in income theory and further, it is because of this reason that we call it a theory of monetary economy. Monetary analysis has led to the denial of ‘money illusion’, rather money occupies the pivotal position. A labourer works for money wages; a capitalist seeks money profits ; and our society has developed money institutions in which the art of making more money has become basic. Money has become the driving force of the economy. The realisation that money is significant enabled economists to reduce a complex image of the economic system to a few social aggregates—income, saving, investment and consumption.

5. Interest—Not Equilibrating Mechanism:

We have already seen that-according to classicals rate of interest brings automatic adjustment between saving and investment at full employment level. This is because they believed that savings depend upon the rate of interest and rise and fall with a rise and fall in the rate of interest (in other words, to them savings are highly interest-elastic and flow automatically to equal investment at full employment level). Keynes, however, challenged the assumptions of the classicals and pointed out that the functional equality between saving and investment is brought about by changes in income (rather than by the rate of interest).

He, therefore, concluded that the equilibrium between S and I is reached considerably below the full employment level, called the under-employment equilibrium. According to Keynes, as long as the shapes of investment schedule, saving schedule and liquidity (demand for money) schedule are as shown further, savings will not automatically flow to equal investment at full employment level; however, flexible wages, prices and costs may be. Therefore, what we have in the economy is the under-employment equilibrium and not the full employment equilibrium.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

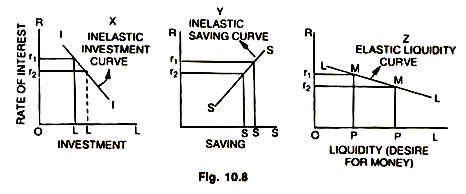

Keynes explains the existence of under-employment equilibrium with the help of the following assumptions:

1. The investment is insensitive (inelastic) to the changes in the rate of interest, i.e., even though there is considerable change in the rate of interest, it has little or no effect on investment.

2. Similarly, savings are also insensitive (inelastic) to the changes in the rate of interest, i.e., even if there is a considerable rise or fall in the rate of interest, it will not lead to any significant rise or fall in saving.

3. Another presumption relates to people’s desire to hold cash (popularly called liquidity function). This liquidity function, according to Keynes, is highly sensitive (elastic) to the changes in the rate of interest, i.e., with a rise in the rate of interest people’s desire to hold cash (liquidity) will go down because people would like to invest money to take advantage of the rise in the rate of interest (rather than keeping it idle). With a fall in the rate of interest people would like to hold more money because it is no more profitable to invest it in bonds and securities.

The shapes of saving, investment and liquidity (desire to hold money) as described above are shown in the diagrams below:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In figure (X), a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 does not lead to any significant rise in investment. Similarly, in figure (Y) a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 leads to insignificant fall in savings. In figure (Z), a fall in the rate of interest from r1 to r2 leads to a considerable increase in people’s desire to hold money (liquidity).

Thus, with these more realistic assumptions about the shapes of the basic functions like savings, investment and liquidity of Keynesian system, it is easy to see that under-employment equilibrium may be the rule in the economy rather than the exception. If the behaviour of the functions is as described above under-employment equilibrium is difficult to avoid as savings do not tend to flow automatically to equalize investment at full employment level, no matter how flexible the wage-price- cost structure may be.

6. State Intervention:

Keynes also denounced the free enterprise economy and its automatic and self-adjusting nature through the invisible hand and price mechanism. Actually Keynes made a strong plea for state intervention in economic matters. As a result of the depression of the ‘1930s’, Keynes started doubting the basic principle of ‘enlightened self-interest’, on which capitalism was supposed to function. Whatever served the interest of businessmen did not serve the interest of the community. Keynes was in favour of giving relief to the unemployed people to boost up effective demand, besides advocating deficit financing and large-scale public expenditure on public works to increase employment.

According to Keynes, the policy of laissez-faire capitalism might have held sway in good old days, but its weaknesses were thoroughly exposed in recent times, specially during the depression when it failed to deliver the goods and services. Keynes, therefore, favoured governmental intervention and viewed government spending, taxing and borrowing as the most important weapon against unemployment.

7. Wages and Propensity to Consume:

Classical economists laid stress on the stimulating effects of wage-cuts on the propensity to consume. Their argument was that a general reduction in wages will result in a general reduction in prices (because marginal costs fall on account of the pressure of lower wage rates). The lower prices will increase consumption. But such an approach represents a vague attempt to apply certain principles relating to the price and demand for a particular product to the problem of total consumption. Actually, the effects of wage-cuts are likely to be more unfavourable on the propensity to consume.

It has been found that wage-cuts may result in more unequal distribution of income as it may be shifted from high consuming groups (the poor) to the high saving groups (the rich) and thus, may lower rather than rise the consumption function. When the wages are cut while the incomes of other groups, like rentiers businessmen remain the same, the wage- profit relationship will be upset. While wages fall, profits and rent continue to increase.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As a result, the propensity to consume of the workers is adversely affected because their purchasing power is reduced as a result of wage-cuts. Further, if the general cut in money-wages is expected to be repeated over and over again, consumers will tend to withhold their demand in anticipation of a further fall in prices, thereby shifting the saving function upwards and depressing the consumption function. It is, therefore, clear that wage-cuts, by redistributing the income in favour of the groups, with lower marginal propensity to consume (and high MPS), will cause income and output, as also the employment, to decline.

8. Liquid Assets and Pigou Effect:

Liquid assets (currency, bank deposits, government bonds and so on) and changes therein also affect the propensity to consume. It has been seen that when people have large amounts of liquid assets (e.g., cash balances, saving accounts, government bonds, share and securities), they show a tendency to spend more on consumption. This is specially true where these assets are more evenly distributed over the various income groups.

Increased liquidity, as a result of the method of financing World War II, undoubtedly had a strong and a stimulating effect on consumption during the years following the war. It is clear, therefore, that more liquid people are, the greater will be the rate of consumption out of any given income.

Prof. Pigou argued that a general fall in prices induced by the general wage-cut will increase the real value of cash balances and other forms of saving thereby leading to a higher rate of consumption. This later relationship (between the real value of liquid assets and consumption) has come to be known as the ‘Pigou Effect.’ ‘Pigou Effect’ in brief, means that the real value of money assets rises as a result of general wage-cut and prices.

The rise in the real value of money assets shifts the consumption function upwards. It is also called ‘Real Value of Money Assets Effect’. But the validity of the ‘Pigou Effect’ has been questioned by modern economists, partly on the ground that a large number of persons do not possess money assets and partly on the ground that those who possess such assets want to possess still more. Under such circumstances, it is highly doubtful whether propensity to consume will be raided through ‘Pigou Effect’. Hence, justification of Keynes criticism of classicals.