Determination of Market Price:

Market price is determined by the equilibrium between demand and supply in a market period or very short run.

The market period is a period in which the maximum that can be supplied is limited by the existing stock.

The market period is so short that more cannot be produced in response to increased demand. The firms can sell only what they have already produced.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This market period may be an hour, a day or a few days or even a few weeks depending upon the nature of the product. For example, in the case of perishable commodities like fish, this market period may be a day, and for cotton textile industry it may be a few weeks. What will be the nature of supply curve in a market period? Two cases are prominent—one is that of perishable goods and the other is that of non- perishable durable goods which are reproducible.

Market Price of a Perishable Commodity:

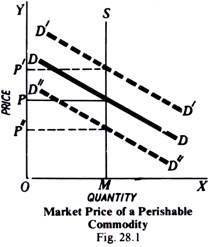

In the case of perishable commodity like fish, the supply is limited by the available quantity on that day, and it cannot be kept back for the next period and, therefore, the whole of it must be sold away on the same day, whatever the price may be. Fig. 28.1 shows the supply curve of fish. Which will be a vertical straight line MS, when OM is the quantity of fish available on that day?

DD is the market demand curve. With perfect competition between buyers and sellers, an equilibrium price OP will be determined at which the quantity demanded is equal to the available supply. That is, equilibrium price will be established at the point where downward sloping demand curve DD intersects the vertical supply curve MS.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now suppose that there is a sudden increase in demand from DD to D’D’. With the supply of fish remaining unchanged, the larger demand will raise the market price sharply from OP to OP’. On the contrary, if there is a decrease in demand from DD to D’-‘D”, the price will fall and the quantity sold will remain the same.

Market Price of Non-Perishable and Reproducible Goods:

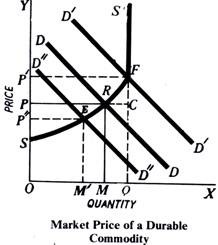

In case of non-perishable but reproducible goods, supply curve cannot be a vertical straight line throughout its length, because some of the goods can be preserved or kept back from the market and carried over to the next market period. There will then be two critical price levels.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The first, if price is very high the seller will be prepared to sell the whole stock. The second level is set by a low price at which the seller would not sell any amount in the present market period, but will hold back the whole stock for some better time. The price below which the seller will refuse to sell is called the Reserve Price.

Given the two price levels, one at which the seller is prepared to sell the whole stock and the other at which he will refuse to sell at all, the amount which he will offer for sale will vary with price. Given his anticipations of future price and intensity of his need for cash, etc., he will be prepared to supply more at a higher price than at a lower one. The supply curve of a seller will, therefore, slope upward to the right. Beyond a price at which he is prepared to sell the whole stock, the supply curve will be a vertical straight line whatever the price.

In Fig. 28.2, SRFS’ is the supply curve of the durable goods while OQ is the total amount of the stock of the goods. Up to price OP’, the quantity supplier varies with price so that at a higher price more is supplied than at a lower one. At the price OS, nothing is sold, the whole stock being held back. Therefore, SF portion of the supply curve slopes upwards from left to right.

At price OP’, the whole of the stock is offered for sale, and beyond the price OP’, the quantity supplied remains the same whatever the price. Therefore, beyond the price OP’, the market supply curve will be vertical straight line (FS’). DD is the demand curve which slopes downwards from left to right. Market price comes to settle at OP, because at this price the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. At this equilibrium price OP, OM amount from the stock is sold, while the rest of the stock, i.e., MQ (= RC) is held back from the market.

Suppose now the demand increases from DD to D’D’, the price will rise to OP’, and the whole stock OQ will be sold. If now the demand, further increases from D’D’ to some higher level, the quantity supplied or sold will remain the same, i.e., equal to OQ, and only the price will rise so that, at the new equilibrium level, the quantity demanded is equal to the available supply. If the demand decreases from DD to D”D”, the price will fall to OP”, and the amount sold will decrease to OM’.

Since, in a perfectly competitive market, the product is homogeneous and no buyer has any preference for a particular seller, therefore, a single uniform market price will be established in the market. Once the market price is determined, an individual seller in the market will take the price as given and constant. Thus, the demand curve which is downward sloping for all sellers is for a single seller a horizontal straight line, i.e., perfectly elastic at the level of the ruling market price.

One important conclusion that follows from the above analysis of price determination in the market period is that costs of production do not enter into the calculation of the sellers, and, therefore, have little influence on the market price.

Determination of Short-Run Price:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have already explained that, in the short run, a firm is in equilibrium at the output at which price equals marginal cost. It must be noted that, during the short run, fixed costs are disregarded in making a decision whether to produce or not. This is because fixed costs have to be borne whether there is any production or not.

Therefore, it is the average variable cost rather than the average total cost which is of determining importance whether to produce or not. If the price falls below the minimum average variable cost, then even in the short run firms will shut down to minimize losses. Thus, the minimum average variable cost sets the minimum limit to the price in the short run, since at prices below it no amount of output will be produced.

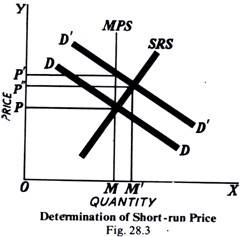

The determination of the short-run price can be explained with the help of Fig. 28.3. Here DD is the demand curve facing the industry. The demand curve as usual slopes downwards from left to right. In the figure, MPS is the market period supply curve and SRS is the short-run supply curve of the industry.

If there is a given increase in demand from DD to D’D’ the market price will rise sharply from OP to OP’, supply of output remaining unchanged. Under the stimulus of this increased demand, the firm will increase production by making intensive use of the existing fixed capital equipment and by increasing the amount of variable factors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It must be recalled that, in the short period, no change in fixed capital equipment can be made, nor can new firms enter the industry. The supply of the commodity will increase as a result of the expansion of output by the existing firms in response to an increase in demand.

Therefore, in the short run, price will fall to OP” at which new demand curve D’D’ intersects the short-run supply curve SRS. Thus OP” is the short-run price, which is higher than the original market price OP, but not as high as the second market price of OP’. The quantity supplied has also increased from OM to OM’. Thus, in the short run, larger quantity of the commodity is sold and price is not quite so high as it was in the market period.

Determination of Normal Price:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Market price may fluctuate due to a sudden change either on the side of supply or on that of demand. A big arrival of fish, for instance, may depress its price in a particular market. A sudden heat wave may raise the price of ice. These are, however, temporary influences and cause temporary disturbances in the market value.

In the absence of such disturbing causes, the price tends to come back to a certain level. This level itself may not be a fixed point for all times. But if the techniques and scale of production remain on the whole constant, this level may be taken as a fixed anchor around which, in its day-to-day movements, the market price oscillates. Marshall has called this level “normal” price.

In the words of Marshall, “‘Normal’ or ‘Natural’ value of a commodity is that which economic forces would tend to bring about in the long run.” It may be pointed out that “‘normal’ prices are not the same thing as ‘average’ prices, unless prices are constant.”Normal prices are those prices to which one may expect prices to tend: average prices will be an arithmetical average of all actual prices. They will not only be influenced by fortuitous fluctuations and oscillations, but will also take account of the general trend towards the ‘normal’ prices”

In order to describe how long-run equilibrium is brought about and thus normal price is determined it is useful ‘ refer to the market period and short-run period also. As we have stated above, the market period is so short that no adjustment in the output can be made. There is a given amount of the stock of the good on hand, and, in case of a perishable good, it must be sold at whatever price the market will bring. Thus, in the market period or very short run, costs of production have no influence on price.

The short-run period, on the other hand, is sufficient to allow the firms to make limited output adjustment. If there is an increase in demand, the firms will expand output using existing equipment to the point where new price equals marginal cost. As shown already, the new short-run price will be higher than the price before the increase in demand but not as high as the market price, and the output will be larger.

In the long period, however, supply conditions are fully adapted to meet the new demand conditions.” If there is a sudden and once-for-all increase in demand, the firms in the long run will expand output by increasing the services of variable as well as of the fixed factors of production. They may enlarge their old plants or build new plants. Moreover, in the long run, new firms can also enter the industry and thus add to the supplies of the product.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

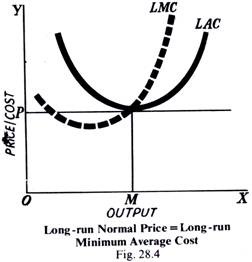

In the long period, average variable cost is of no particular relevance, since in the long-run all factors are variable and none is fixed. In this period, all costs ever incurred by the firm must be covered and hence all are price-determining. Price in the long-run or normal price, under perfect competition, therefore, must be equal to the minimum long-run average cost (see Fig. 28.4). Here Price OP= LAC = LMC.

We explained that a firm under perfect competition is in long-run equilibrium at the output where Price = MC = AC. If the price is above the minimum long-run average cost, the firms will be making abnormal profits and, in the long run, new firms will enter the industry to compete away these profits and the price will fall to the level where it is equal to the minimum long-run average cost.

Nor can the price fall below the minimum average cost, since in that situation the firms will be incurring losses and, in the long-run, if these losses persist, some of them will leave the industry, and thereby the price will rise to the level of minimum average cost so that in the long run firms are earning only normal profits.

Thus, we see that if the price is above or below the minimum long-run average cost, adjustment takes place in the output largely by the entry or exit of firms so that new price once again equals the minimum average cost. But whether this long-run minimum average cost is equal to or is higher or lower than the previous one depends on whether the industry in question is constant cost, increasing cost or decreasing cost industry. How the normal price is determined under conditions of diminishing returns, constant returns and increasing returns is explained below.

Influence of Laws of Returns on Normal Price:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The influence of the laws of returns on the normal price brings out clearly the importance of the time element in the theory of value. The scale on which a commodity is produced affects its cost of production. But, during a very short period, the scale cannot be changed and hence cost of production remains unaffected. Thus cost of production, in the very short period, can have no influence on market price. The laws of returns can exert influence only in the long run, and can, therefore, affect only the normal price.

Let us suppose that the demand for a commodity increases. The market price, i.e., the price at the moment, must rise. The producer will try to increase the supply with the existing equipment to take advantage of the rise. Although supply will increase in the short period to some extent, yet it will not be enough to bring the price down to the old level. Hence, price will remain high somewhat. But we cannot be sure about the normal price, i.e., the price in the long run. In order to find out what will happen to the price in the long run, we must know the particular law of return to which the industry is subject.

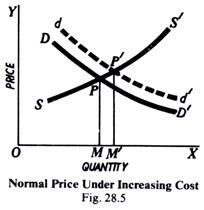

Normal Price in Increasing Cost Industry:

Suppose the industry which produces the commodity is subject to the law of diminishing returns (or increasing cost industry), e.g., coal. Now, when demand has increased, the market price of coal will rise. The producer will increase the supply to take advantage of this rise. The scale of production will increase. But, because the law of diminishing returns prevails in the industry, the large the output, the higher will be its cost of production.

Thus, the additional supplies are obtained at a higher cost. This means that the price in the long run will be higher. The normal price will rise. This will be the case with all agricultural products like wheat, rice, sugar-cane, and the products of other extractive industries, e.g., mining and fishing.

Let us illustrate it diagrammatically. The supply curve SS’ in Fig. 28.5 shows diminishing returns (or increasing costs) when more coal is produced. The rise m demand is shown by the new (dotted) curve dd’ in place of the old DD’.

The old equilibrium price PM shifts to a new one M’P’ as a result of increased demand. If demand for coal increases the price will immediately rise. Ultimately the price will rise still more, for the increased production will be obtained at a higher cost. This is due to the law of diminishing returns, for the more you produce the more is the cost, and the less you produce, the less is the cost.

In the above diagram, the old price was PM for quantity OM and it rises to P’M’ when OM” is demanded and produced. In the same manner, it can be easily shown that a decrease in demand for coal will reduce the price much more. This is so because reduced production will be obtained at a lower cost when the law of diminishing returns operates.

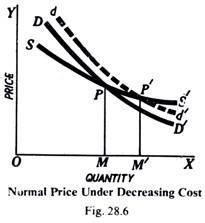

Normal Price in Decreasing Cost Industry:

But suppose the industry is subject to the law of increasing returns to decreasing cost industry), e.g., cloth. Suppose the demand for cloth increases due to a rise in the standard of living or increase in population. The increase in demand means higher market price; the higher price leads to production on a larger scale.

The larger the scale, the lower the cost on account of the operation of the law of increasing returns in cloth. When, therefore, demand has increased permanently, the normal price will fall. This will happen in the case of all manufactured and machine-made goods like cars, cycles, soap, biscuits, fountain pens, radio-sets, etc.

This change can be illustrated with the help of a diagram (Fig. 28.6). Here, the supply curves SS’ shows that cloth is manufactured under the law of decreasing cost or of increasing returns. The cost falls with increased production. The rise in demand is shown by the new (dotted) curve dd’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The old equilibrium price was PM but with the rise in demand to dd’, the price falls to P’M’, the new equilibrium price. In the same manner, a little thinking will snow that if the demand for a commodity the production of which is subject to the law of increasing returns falls, normal price will rise, as reduced production will be obtained at a higher cost per unit.

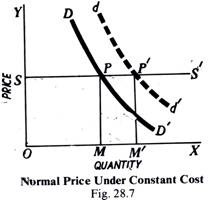

Normal Price in Constant Cost Industry:

In case, the industry is subject to the law of constant returns, the cost of production remains the same whatever be the scale of production. The change indemand will no doubt lead to a change in supply. The scale of production will be altered, but the cost per unit will remain the same. Such a condition does not persist for any length of time and occurs only when the laws of increasing and decreasing returns are equally balanced. In such cases, therefore, for a period of time the normal price remains unchanged.

To illustrate diagram metrically let us suppose the supply curve SS’ (in Fig. 28.7) represents the production of a commodity like wheat under the law of constant returns for a period when the tendency towards diminishing returns is checked by improved methods. DD’ is the old demand curve, while the rise in demand is shown by the dotted curve dd’.

The rise in demand does not affect the price. The old price PM is equal to the new price P’M.

Conclusion:

We may thus conclude that if demand increases, price will immediately rise but ultimately it will rise, fall or remain constant, according as the industry is subject to the law of diminishing returns, increasing returns or constant returns, respectively. In case of decrease in demand, the effect on normal price will be the opposite. This is how the laws of returns influence price. We repeat that they cannot influence market price, i.e., price at any given moment. They can only affect normal price, i.e., price in the long run.