In this essay we will discuss about the industrial labour in India. After reading this essay you will learn about:- 1. Essay on Industrial Labour 2. Essay on the Trade Union Movement 3. Essay on the Industrial Disputes in India 4. Essay on the Machinery for the Settlement of Industrial Disputes.

List of Essays on Industrial Labour in India

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Industrial Labour

- Essay on the Trade Union Movement

- Essay on the Industrial Disputes in India

- Essay on the Machinery for the Settlement of Industrial Disputes

1.

Essay on Industrial Labour:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The development of modern factories, mines, transport and plantations resulted in the erh^rgence, during the second half of the 19th century, of an entirely new class of Indian society, namely, the industrial working class. This class, comprising the Indian men, women and children working in modern industries, was subjected to as ruthless and revolting an exploitation as is known to modern man.

On its sweat and toil, suffering and privations, was raised the structure of India’s industrial development. A study of the living and working conditions of this class is but appropriate.

Wages and Standard of Living of Industrial Labourers during Different Periods:

The task of measuring the changes in the working class levels of living in India is not easy. The data is scanty, especially in regard to the 19th century. Besides, it is faulty and also capable of different interpretations. Despite these limitations, a study of the workers’ standard of living in India can be conveniently divided into certain broad well-defined periods.

1861-1905:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This period was marked by two main features: extremely low wages and a rising price level. In Bombay, the daily wages paid by the P.W.D. were 37 paise, 25 paise and 18 paise in 1867 68 but they came down, in 1871 — 72 to 30 paise, 18 paise 13 paise to a male, female and child labourer respectively.

In Punjab, the highest rate in 1867 — 68 was 30 paise per day chiefly in parts where public works were going on and the lowest rate was 12 paise only. In Bengal, the average daily rate paid by P.W.D. ranged from 7 paise to 13 paise. In C.P., it was only 18 paise in 1870.

These ‘pittance’ wages coupled with a rising price level kept the workers close to starvation. It was this miserable condition of the workers which prompted Ramsay Macdonald to observe that “the poverty of India is not an opinion, it is a fact.”

From about 1873, money wages began to rise both in the town and countryside. The greatest rise was recorded in Bombay, Bengal and Punjab, the rates of increase for agricultural labourers being 39% in Bengal and 49% in the Punjab and for artisans, 48% in Bengal and 50% in Punjab during the period 1873-1903.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the Bombay Presidency, the increasing demand for labour in the cotton Textile industry pushed the wages higher with the result that it created conditions of scarcity in some of the agricultural districts. Labourers from U.P., C.P., Bihar and Madras migrated in large number to the Punjab, Bengal or Bombay thereby raising wages in the districts from which they came.

This led the government to claim that the standard of comfort of workers had improved. As evidence, were cited the increased consumption of salt, large development of excise revenue, and the large increase in the post-office Saving’s Bank deposits.

True picture, however, is revealed when we compare the money wages with the cost of living. As Dr. Kuczynski has pointed out, between 1880—1905, money wages rose from 82 to 107 (1900 = 100), a rise of only 30%. On the other hand, the index of the cost of living increased from 77 to 91-an increase of 18%. Real wages, therefore, recorded only a nominal rise of 11% from 106 in 1880 to 118 in 1905.

It is evident that there was only a marginal increase in the real wages of the workers. However, labourers in certain urban centres as well as skilled artisans like blacksmiths and carpenters appear to have improved their position due to the spread of railways, rise of new industries like cotton, jute, mining and the emergence of new trading centres.

1905-1914:

This period saw “the existence of famine prices without famine.” The prices of hides and skins, food grains, building-materials and oilseeds rose more than 40% above those of 1890; cotton and jute rose about 33% and 31% respectively. Consequently, the general weighted prices index rose from 135 in 1905 to 187 in 1914.

The cost of living went up without a corresponding increase in wages, making it more and more difficult for workers. According to Kuczynski, worker’s money wages rose by 19% between 1905 —14, but cost of living by 43%. Consequently, real wages declined by 17%. No wonder, there was a general labour unrest in the country, especially among the industrial workers.

There were strikes in Bombay mills, East Bengal State Railway, and in the government press at Calcutta. The highest point was reached with the six day political strike in Bombay in 1908. A number of trade unions also came up during this period- notably, the Printers’ Union, Calcutta, (1905), The Bombay Postal Union, (1907) and the Indian Telegraph Association, 1908.

The First World War saw a further steep rise in the price- level. Consequently, cost of living in January, 1919 was higher by 83% when compared with the average of July, 1914. A war allowance was sanctioned but it was insufficient.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Between 1914—19 , increase in wages was 54% in spinning and weaving industry, 19% in Kanpur Woolen Industry, 16% in coal mining, 19% in tea, 28% in the engineering workshops —the overall average increase in money wages being only 21½%.

In view of the much greater rise in the cost of living, there was great discontentment and restlessness which found expression in a series of strikes in 1920. It is only in the inter-war period that there was some improvement in the real earnings of workers.

The reason was that prices in this period were continuously falling, especially after the great depression, while workers were sufficiently awakened and better organised to make wage reduction extremely difficult. That is why this period, between the two world wars, recorded a 45% rise in the real wages of the workers.

This increase in real wages, welcome though, does not reflect the reality because it excludes the losses through unemployment and underemployment during the depression. Furthermore, it also overlooks the fact that the employers often raised the prices of food articles sold at the factory shop with a view to depress the wages of workers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It also ignores the system of factory punishment which enabled the management to make wage deductions, quite arbitrarily. It can, therefore, be safely concluded that although the real wages rose in the inter-war period, yet the rise was not as high as is generally supposed.

The Second World War was a period of inflationary rise in prices. Although wages were somewhat increased; an additional dearness allowance was also sanctioned, yet the ever-soaring prices raised the cost of living and reduced the real wages.

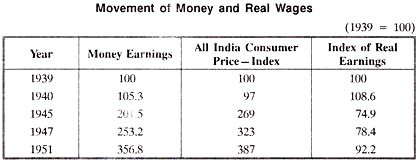

According to a U.N. Survey, average annual money earnings in rupees in British India rose from Rs. 287.5 in 1939 to Rs. 595.5 in 1945-an increase of 107%. But even this spectacular increase in money wages did not compensate the workers for the steady rise in the cost of living, the index having risen to 277 in 1945. Real wages, consequently, registered a sharp decline.

Prices continued to rise even after the war was over. The cost of living index rose from 100 in 1945 to 138 in 1949; money earnings from 100.3 in 1945 to 168.5 in 1949 but the index of real earnings rose from 100.3 in 1945 to 122.1 in 1949 (1944 = 100).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although the real earnings of factory employees, thus, increased by 22% between 1944 — 49 but they were still 7% below the pre-war level. Industry wise, the highest increase was recorded by chemicals and dyes and the lowest in the ordinance factories. Province-wise, workers gained the most in Orissa and the least in the Punjab.

The broad picture which emerges of the war and post-war period is that real earnings started declining from the year 1940, reaching rock bottom in 1943 when they were 33% below the 1939 level.

By 1945, they picked up a little but steady recovery took place after Independence only on account of the upward revision of wages granted by Industrial Tribunals. However, the loss in real earnings that had taken place during the war had not been recouped by 1951, real earnings being still 7.8% below the 1939 level.

Five-Year Plans and Wages:

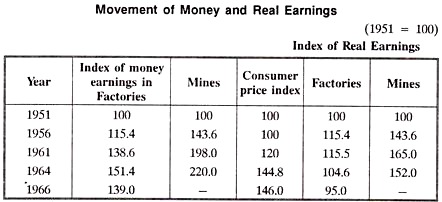

The per capita average annual money-earnings of workers earning less than Rs. 200/- per month rose almost continuously over the entire period 1951-64 —the level in 1964 being roughly 1.5 times that in 1951. Within this period, there was a rise of nearly 13% during 1951-55, 19% in the next five years (1955-60) but, during the next four years, 1960-64 average money earnings rose by a little less than 13%.

Since the cost of living declined by 8.6% during 1951-55, there was an improvement of the order of 24% in the real earnings per worker. During 1955-60, the rise in the cost of living was about 29% and the real earnings showed a decline of about 8% when compared with 1955 although the level of real earnings in 1960 was still about 14% above the 1951 level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In 1961-62, the level of real earnings again picked up, but 1963 and 1964 witnessed a significant decline bringing the 1964 real wage level nearer to 1951. Thus, during 1951-64, real wages showed little improvement while in 1964, there was a substantial decline.

Province-wise, there was wide variation. Maharashtra with Rs. 1684/- and Andhra with Rs. 950/- formed the two extremes between which the average annual earnings of workers getting less than Rs. 200 a month lay. Industry-wise, the earnings were the lowest in Jute textiles and highest in products of Petroleum and coal.

The money wages of mine workers had almost doubled by 1961 though the increase in real wages was only 65%. In fact, but for the year 1953, real wages of mine workers were continuously rising and they reached the peak in 1963. Although the great rise in prices during 1964 led to their decline, yet they were 52.5% higher in 1964 as compared with 1951.

The great rise in the earnings of mine workers can be explained by the fact that money wages in the base period (1939) were extremely low-much lower than in factories-and their upward revision from 1956 led to a great rise in the real earnings of workers.

In plantations, the situation appeared to be somewhat better than in factory establishments. In ports and docks and in some sections of white collar employments also, workers secured some gains.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the whole, between 1952-65 while per capita money income improved the real wages of workers had, with few exceptions “at best not fallen.” The condition deteriorated in 1965-66 when there was a further rise in the cost of living.

Family Budgets:

The average income of the workers being very small, a very high proportion of it was spent on food and other basic necessities of life. The 1921-22 enquiry into family budgets, conducted by the Labour Office of the Bombay Government, revealed that the expenditure on food varied from 60.5% in the case of income below Rs. 30/- per month to 52.6% in the case of incomes between Rs. 80-90 per month.

And yet, the average adult male worker consumed less of almost every commodity than was prescribed by the Bombay Famine Code or for the prisoner in the Bombay jails. As a jail diet is considered to be on the borders of a subsistence minimum, it is evident that the factory worker in India lived below the margin of subsistence and his food condition as a free labourer was worse than that of convicts.

During the war, the calorie-intake of industrial workers was severely reduced due to general food shortage and the consequent introduction of rationing.

The Health Survey and Development Committee (1943) reported that the staple diet of workers in Madras and Bengal was particularly of a low quality while milk consumption was unsatisfactory in all parts of the country. The situation showed no improvement even after the war was over.

The enquiry into the cost and standard of living of Plantation labour in South India (1948) showed that 95.7% of workers were getting less than 3,000 calories a day; 100% were getting less protein, 89.6% were getting less calcium and 47.8% were getting less iron than the required dose.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

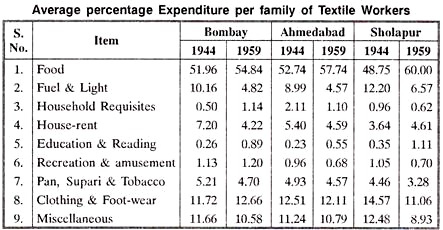

The Economic Times, while comparing the position of textile workers in 1944 with that in 1959, found that percentage expenditure on food, demand for which is inelastic, increased in all centres in view of the rising prices in the country.

There was no qualitative improvement either since at all centres, % age expenditure on milk products, vegetables, sugar, sweets, tea and refreshments declined. Likewise;, such conventional necessaries as pan and supari also showed a decline. Expenditure on recreation and amusement also fell. The only redeeming feature was a marginal increase in expenditure on education.

Indebtedness:

A very noticeable feature of the economic life of the industrial workers in India was that they were generally in debt. This fact was referred to by various labour committees and commissions which were set up from time to time.

For instance, the enquiry made into the working class budgets in Bombay city in 1921-22 revealed that 47% of the families were in debt and the average indebtedness amounted to 2½ month’s earnings and the usual rate of interest was 75% which was frequently exceeded.

The Royal Commission on labour estimated that, in most industrial centres, the proportion of families or individuals in debt was not less than two-third of whole and that, in the great majority of cases, the amount of debt exceeded three months’ wages.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Commission was impressed by the number of cases in which an industrial worker was obliged to curtail his expenditure on necessities to meet interest charges “without the faintest prospect of being able to reduce the principal.”

The Family Budget Enquiries undertaken by the Government of India (1943-45) revealed that 64.1% of the families in Bombay, 85.7% in Sholapur, 62.2% in Jamshedpur and 72.3% in Madras were in debt. Average debt per family ranged from Rs. 79 in Madras to Rs. 234.69 in the comparatively better-off centre of Jamshedpur.

Recent enquiries (1959) show that in Bombay, 42.62% of the families were in debt ranging from Rs. 500-1000 while at Ahmedabad, the %age was 32.72 and 20.37% of these were in debt ranging from Rs. 1000-2000.

Speaking of the causes of indebtedness, the Royal Commission on Labour found that “many are born in debt” and expressed admiration for the son who “assumes responsibility for his father’s debt, an obligation which rests on religious and social but seldom on legal sanction.” The Rege Committee (1946) agreed that, in some cases, indebtedness was, no doubt, due to extravagance, vice and improvidence.

But, according to the committee, “the root cause of the evil is the want of any margin left for meeting the expenditure of an unforeseen character. It is true that one of the main causes of indebtedness is the expenditure incurred on marriage, funeral, etc. — The worker is a part of a social organisation, and has perforce to conform to certain customary social standards even when he is not in a position to do so.”

The 1959-committee found that, among the causes, deficit on current account came first, accounting for 44.78% of the loans at Madras, 34.65% at Calcutta, 29.39% at Bombay. Sickness came second, accounting for 22.04% at Calcutta, 21.96% at Bombay, 14.37% at Madras.

Other causes were festivals, marriage, (7-29%) child-birth and unemployment. In view of the serious cut in the worker’s income which the debt imposes, it is misleading to assume that money wages are in any sense a measure of their standard of living.

Housing:

The poignancy of the utter poverty of the Indian worker can be best realised from the way he is housed. In some of the new townships like Bhillai, Durgapur, Rourkela and Bhopal, where several public sector industries were set up, the problem of housing factory workers had been satisfactorily solved.

In some older centres of Mumbai, Kolkata, Madras, Kanpur, and Ahmedabad also, some enlightened entrepreneurs found it advisable to supply housing accommodation to the employees in the hope of commanding the best labour force in the market.

However, in practically every industrial centre, the problem of over crowding was allowed to grow, no control having been exercised over industrial housing. This naturally led to a deplorable state of affairs.

In the words of the Royal Commission on Labour, “in the busiest centres, the houses are built close together, cave touching cave, frequently back to back, in order to make use of all available space. Indeed, the place is so valuable that, in place of streets and roads, narrow, winding lanes provide the only approach to the houses. Neglect of sanitation is often evidenced by heaps of rotting garbage and pools of sewage, while the absence of latrines enhances the general pollution of air and soil. Houses, many without plinths, windows and adequate ventilation, usually consist of a single small room, the only opening being a doorway, often too low to enter without stooping. In order to secure some privacy, old kerosene tins and gunny bags are used to form screens which further restrict the entrance of light and air. In dwellings such as these, human beings are born, eat and sleep, live and die.”

Thus was summed up the general picture of the Busties of Kolkata, Chawls of Mumbai, the Cheries of Chennai and the Ahatas of Kanpur and the Dowrahs of Coalfields.

The effects on ill-health arising from insanitary conditions were aggravated by overcrowding. The Rege Committee (1944-46) found the worst-ever crowding in the jute mills where a room including a verandah, 80 square feet in size, provided accommodation for 9 persons on an average.

In the Ahatas of Kanpur, a single room of 8′ X 10′ was found shared by 2 or 3 or even 4 families and the doorways were so low that the workers had “to crawl” to enter their dwellings.

In Mumbai, the committee found that a tenement in each chawl provided, on an average, only 26.86 feet per person. That industrial housing did not show much improvement even in the post-independence period is well brought out by the Family Living Survey among industrial workers, 1958-59.

The survey found that 91% of the workers’ families in Mumbai, 80% in Calcutta and 63% in Kanpur lived in Chawls/busties. Of these 42% in Mumbai 47% in Kanpur, 56% in Kolkata had no satisfactory sewage arrangements. The Survey further found that 90% of the dwellings in Ahmedabad, 90% in Chennai, 96% in Mumbai and 89% in Kolkata were one-roomed.

Such was the condition of those who were lucky enough to get some accommodation. But there were many-roughly 45% in 1963 who, having no shelter of any kind, lived and died on the roads. Their plight can be better imagined then described.

Not that the government was unaware of the situation. As early as 1918, the Indian Industrial Commission presented a faithful picture of the filth and squalor of chawl life of the ill-ventilated rooms, the damp ground floors, the narrow courtyards dumped with rubbish, the insufficient water arrangements and the bad sanitary condition.

Thirteen years later, the Royal Commission on labour, repeating the story of neglect and indifference to the question of workers’ health and housing, emphasised that the time for inaction and delay was past and that “a beginning should be immediately made.”

The Rege Committee pointed out that “no attempt at raising the standard of living of the industrial worker could be successful without an early solution of the housing problem.”

And yet, not much was achieved despite various housing schemes launched by the government, on the words of the National Commission on Labour “the total picture which emerges in this regard (housing) is still not very different from those described by the Whitley Commission or the Rege Committee, although there is a larger proportion of new houses to relieve monotony.”

The absence of adequate housing accommodation brought with it serious moral, social and health problems. The overcrowding of people in dark ill-ventilated quarters was one important cause of high infant mortality and tuberculosis But more serious was the moral degradation it involved.

Adjacent to the busties and sometimes even in their midst, were brothels and liquor shops offering an easy and cheap temptation to workers for ‘decreation’.

To sum up the standard of living of the Indian worker was appallingly low. Living on a diet which invited diseases of all kinds, sunk in indebtedness and housed in hovels of a most insanitary character, the Indian industrial worker lived in an environment “which, in other countries, would be favourable to a revolutionary outburst.”

2. Essay on the Trade Union Movement:

The foundations of modern industry in India were laid in the middle of the 19th century. Plantation of tea, cotton and jute manufacturing, coal mining, all started between 1850 — 60. These newly-started mills enjoyed unrestricted freedom in regard to the employment of labour and this understandably resulted in deplorable working conditions as well as the association of women and children with factory work.

A striking feature of the labour scene was the total absence of effective public opinion against the exploitation of factory workers. There was no Robert Owen or Shaftsbury to advocate their cause. The great religious, or social revival in 1870’s failed to awaken the social conscience in favour of the working class.

The Government was dominated by the Laissez-Faire principle so much so that it appeared to be more keen “to protect the social system from the workmen rather than to protect the workers from the social system.” Workers themselves did make some isolated attempts to voice their demand for lessening the hardships of industrial life.

For example, there was a ten days’ sweepers’ strike in Bombay in 1866; in 1867, the butchers of Bombay struck work Industry- wise, the plantation industry was the first to witness “assaults and riots.” In the cotton textile industry, there was a ‘Protest’ strike in 1877 over wages in the Empress Mills, Nagpur.

According to R.K. Das, there were 25 important strikes recorded between 1882-90 in different factories of Bombay and Madras. These strikes, which were more in the nature of ‘elemental revolts’ generally ended in defeat for the workers because employers were very powerful and workers were not yet united and organised.

It was at this juncture that Sorabji Shahpurji Bengali, a social worker, started an agitation for factory legislation. He won the sympathy of the Lancashire industry and the public opinion in India and as a result of his ceaseless efforts, the first Factory Act was passed in 1881. Bengali and his friends were, however, not satisfied and they continued their agitation for further improving the working conditions of factory hands.

In September, 1884, two public meetings of textile workers were organised in Bombay to protest against the wretched conditions of work in factories. A petition was adopted at the meeting demanding a weekly holiday, half an hour’s mid-day rest, regular payment of monthly wages and compensation in case of accidents.

The petition signed by 5,500 workers was presented to the president of the commission which was appointed to make recommendations regarding the improvement of the Factories Act. This can legitimately be regarded as the beginning of the labour movement in India.

A number of a sort of unions soon emerged. The first was the Bombay Mill hands Association formed in 1890 by Shri Lokhanday followed by the Mohammedan Association set up in 1895. The amalgamated Society of Railway Servants of India and Burma was formed in 1897.

The Printers’ Union, Calcutta and the Bombay Postal Union, after a few months’ existence, became defunct. The Kamgar Hitvardhak Sabha, started in 1909, was not a trade union but a welfare centre “to mitigate, in some measure, the evils of the industrial system such as monetary difficulties, agricultural and industrial indebtedness, overcrowding, insanitary condition……. “ and such other problems.

These early unions were of a sporadic or ad hoc nature. Most of them had no regular constitution, no funds, no regular membership and no programme of action. They bore little resemblance to the fighting unions of today and were more in the nature of ancient guilds or friendly societies.

A few like the Amalgamated society of railway servants had, as one of its aims, “the avoidance of strikes upon the part of its members by every possible means.”

Naturally, their agitations were irregular and isolated and not organised as part of a movement. What is more, many of these unions were sectarian in character. For instances, the officials of both the Bombay Millhands Association and the Kamagar Hitvardhak Sabha belonged to the backward Maratha communities.

Likewise, the membership of the Amalgamated society came from Europeans and Anglo-Indians only while the Mohammedan Association enrolled Muslims only. Besides, these unions were, as Ornatidescribes, “for the worker rather than by the worker.”

They were not led by workers themselves but by social reformers. That is why the conferences and agitations of this period were sponsored with a view to making appeals to the government rather than to force it to give the workers their due rights.

It was really the First World War which pushed the Indian working class into a new phase of organisation. The ferment of war brought about a radical change in the outlook of the industrial workers as a class and this change, as the Royal Commission on Labour observed, was related “to the realisation of the potentialities of strike.”

A strike epidemic swept through the country during 1918-22 and the formation of the unions either immediately preceded a strike or was the result of its successful termination. Apart from this, there were four other factors which especially favoured the growth of the movement. In the first place, Mahatma Gandhi had come on the political horizon with his programme of achieving independence for the country.

The political movement, launched by him, not only brought political awakening to the working class but also provided the services of educated intelligential to lead it. Further more, the treatment meted out to Indian labour in South Africa created a stir in the country and led to greater solidarity with the working class. Secondly, the Russian Revolution had created a world-wide revolutionary fervour.

New ideas came to be preached and new aspirations began to be cherished. The Indian working class was also electrified; restlessness and a spirit of defiance on its part became soon manifest. A third factor was the establishment of the International Labour Office which lent a new dignity to the working class.

The provision of electing labour delegates on the recommendation of the most representative labour organisation brought about the creation, in 1920, of the All India Trade Union Congress. However, the fourth and most important factor was economic.

When the war broke out and prices rose high and shortage of food and other consumer goods developed, the whole burden of the economic crisis fell upon the shoulders of workers. They silently bore the burden for a time, but when it became unbearable, dissatisfaction and resentment developed in their ranks; a protest began to take shape and out of that protest was born the trade union movement in India.

The first trade union formed on modern lines, was the Madras Labour Union set up by B.P. Wadia in 1918. Soon the movement spread to other centres and by 1920, there were 125 unions with a membership of 2.5 lakhs.

The movement however, received an unexpected blow when the Madras High Court, giving judgement in a suit field by Biny and Company against the office-bearers of the Madras Labour Union, declared trade union activity as an illegal conspiracy and restrained Wadia and his followers from further interference in the working of the mill.

The judgement came as a rude shock to the workers who realised for the first time that they could be prosecuted also for genuine trade union activity. Thereafter, the workers’ whole effort was directed towards securing legal recognition for the movement.

N.M. Joshi, the veteran trade union leader and a nominated M.L.A, brought the question before the Assembly in March 1921. His persistent efforts in this connection finally bore fruit when the Trade Union Act was passed in March 1926.

Under the Act, any seven persons could form a union and have it registered with the government. Registration, however, was not compulsory although certain privileges were conferred on registered unions. The Act required a registered union to define its name and the objects for which it was established. It was further required to keep a list of members and provide for regular audit of its funds.

The Act provided that not less than half the office-bearers must be employed in the factory/industry covered by the Union. Against these restrictions, the Act granted protection to trade union workers against civil and criminal action for genuine trade union activity.

A registered trade union was permitted to create a fund, purely on voluntary basis, for the promotion of civil and political interests of its members. The passing of the Act was great landmark in the history of the trade union movement. The fear of prosecution being over, unions began to be formed in large numbers. By 1927-28, the number of registered unions had reached 29 with a membership of 101,000.

It was in 1920 that India’s first central organisation of labour, namely, The All India Trade Union Congress, was formed with a view “to coordinate the activities of all labour organisations in all trades and in all the provinces of India, and generally to further the interest of Indian labour in matters, economic, social and political.

In its early years, the A.I.T.U.C. was only a top organisation with no commendable record of real organisation, service or achievement except that it used to meet once a year to discuss important matters, pass resolutions and recommend candidates for the International Labour Conference.

Even so, differences regarding the basic character of the trade union movement soon emerged. While one section desired to develop it as a constitutional movement for the protection and advancement of the economic interests of workers, the other, led by the communists, was bent upon transforming it into a revolutionary movement for the establishment of a new order of society.

The differences were soon to come to a head and lead to a parting of ways.

Meanwhile, the year 1928 was one of great industrial unrest and trouble. The number of trade disputes was only 203 but 316,47,407 man-days were lost. In Bombay, where the communists had entrenched themselves, the textile workers went on a six months’ long general strike directed against measures of rationalisation and wage-cut.

The government felt alarmed and took a series of measures such as the appointment of the Royal Commission on Labour. The Trade Disputes Act, 1929 and the appointment of the Bombay Riot Enquiry Committee. To cap it all, the government launched the famous Meerut Conspiracy case in March in 1929 in which 31 trade Union leaders were arrested in half a dozen cities on charges of conspiracy against the government.

The trial became a ’cause celebre’ all over the world and created a whirlwind of public opinion in its favour. Although the removal of these leaders from the field led to improvement in the industrial situation for sometimes, but ‘far from damning communism, the case encouraged it.’

The history of the movement from 1929-38 is the story of splits and unity. The All India Trade Union Congress, which was already riven with dissension over basic policy matters, was split in 1929 when communists gained control of the organisation and the moderates left to form the Indian Trade Union Federation.

The movement was further split in 1931 when the extremists led by Ranadive and Despande left to form the All India Red Trade Union Congress.

This was most unfortunate and costly just at the time when the lengthening shadows of the Depression had prompted wage-cuts and rationalisation. In 1933, more than 50,000 workers in Bombay city were thrown out of employment and by 1934, almost every mill in Bombay had brought the wages down.

The workers’ strike in Calcutta, The Tata colliery worker’s strike and the Textile workers’ strike in Bombay all ended in failure.

The communists launched the general strike in 1934 against rationalisation in Bombay, Nagpur and Sholapur. The government came down with the Emergency powers Ordinance under which the communist party was banned and more than a dozen registered trade unions declared illegal. Some strike leaders were detained and others prosecuted under the Trade Disputes Act.

Thus, the labour movement was shattered in sprits, its leaders removed and its ranks divided. This made the climate favourable for complete unity in its ranks. In 1935, the Red Trade Union Congress merged with the All India Trade Union Congress.

A new political party, called the Congress Socialist Party, also jointed the A.I.T.U.C. Final unity was achieved with the merger of the National Trade Union Federation with the A.I.T.U.C in 1938.

The Government of India Act, 1935, allotted 10 seats in the Federal and 38 in the Provincial Assemblies to labour representatives to be elected by registered unions. This encouraged the unions to register themselves. The installation of popular Congress ministries in 1937 gave a further boost to the movement.

The greater freedom enjoyed by the workers and the sympathies obtained by them from the Congress ministries in the assertion of their right to organise led to a remarkable growth of the movement. By 1938-1939, the number of registered unions rose to 562 and their member ship to 3,99,159.

The onset of the Second world war in 1939 created fresh opportunities for the movement to grow. In the first place, there was a large increase in the number of employed workers. Organisation was needed to put forward their demands and to agitate for them.

Secondly, on account of the rapidly rising prices, demand for increase in wages and dearness allowance was inevitable and demands such as these could only be put forward through trade unions.

Unions, therefore, grew in all parts of the country, in all trades, and all industries. This may be seen from the number of registered unions which grew from 562 in 1939 to 865 in 1945 while the membership of unions submitting returns increased during the period from 3,99,159 to 8,89,388.

Their financial position also improved. They became more stable organisations with members who paid their fees regularly. They also began to have their own regular offices with some paid staff of their own. Some of them even began to take interest in educational and cultural activities.

Another noticeable war-time development was the association of white-collar workers with trade union activity. In some cases, they formed their separate unions; in others, they joined hands with manual and industrial workers to form common unions. Trade unionism thus grew in banks and insurance companies, in commercial and industrial organisations and even in government offices.

While individual unions made rapid progress in numbers as well as membership, the trade union movement, as a whole, got weakened. This was due to its inability to take a firm and clear attitude towards the war. One group led by M.N. Roy regarded the war as an antifascist struggle and advocated whole-hearted and un-conditional cooperation in the war efforts.

At the other extreme were the communists who, till Russia was attacked in December 1941, regarded the war as imperialist and stood for active efforts to sabatage it. All attempts to reach agreement having failed, the Roy group left to form the Indian Federation of Labour. The working class unity, built so laboriously, thus broke down and the movement was split once again.

The war years were years of high prices and acute sacrifices. But the years which followed were far more difficult as the prices rose higher and food grains and other essential commodities became more and more unavailable. Index of real wages, therefore, declined to 73.2 in 1946 as against 100 in 1936.

The real distress was, however, greater on account of the prevailing profiteering, black- marketing and hoarding in the country. Under the circumstances, there was bound to be widespread discontentment which manifested itself in growing trade unionism. The number of unions rose to 1225 and their membership to 13,31,962.

A notable development in the immediate post-war period was the formation of Indian National Trade Union Congress on 4, May 1947. Soon afterwards, in 1948, the Congress socialists also left the A.I.I.U.C. to merge with the National Federation of Labour and formed the Hind Mazdoor Sabha.

The establishment of these Unions led to the final parting of ways between diverse political groups which had so far worked together. Mention may also be made of the Trade Union (Amendment) Act, 1947.

The Act contained a provision for compulsory recognition of representative unions by the employers. Another redeeming feature was the appointment of Labour courts to decide disputes arising out of the refusal of employers to recognise a union. The act was, however, never enforced.

The Five Year Plans gave, both in theory and practice, a new direction to the movement. According to the Planning Commission, “the attitude to trade unions should not be just a matter of toleration. They should be welcomed and helped to function as part and parcel of the industrial system.”

It was in this social and economic atmosphere that trade unions operated since independence. And helped by such factors as “the changed outlook towards labour organisations, the new spirit of awakening in the country and the economic distress that followed the war years —as well as the desire of political parties to help labour as much as to seek help from it”, the trade union movement took rapid strides.

The total number of registered unions stood at 13,023 in 1964-65 and membership at 4.14 million.

Even with this rapid growth, the movement covered only a small fraction of the industrial working force. According to one estimate, the proportion of union members to the total number of workers in 1962-63 was about 24% in sectors other than agriculture. In other words, the majority of the Indian working class lay outside the influence of the movement. There were several factors responsible for the slow growth of the movement.

Causes of Slow Growth:

The first and foremost was the slow growth of industries. Unless industries developed and prospered, no trade union could have secured gains for its members and without security gains, unions could not develop and get strong.

Another difficulty was the absence of a stable working force. The industrial worker came from a close and well knit rural environment. Born and bred amidst the affections of his parents, brothers and sisters, he often felt lost in the fast but impersonal city life. It took him a long time to get used to city environment. Working class developed only after a long time and hence the slow progress made by the movement.

Helpless, backward and ignorant as the industrial worker was, he was not in a position to build up, by himself, an organisation. His helplessness was further increased by the fact that he was ignorant of the English language through which alone all official business was transacted.

He had to rely on outsiders who could show him how to organise as well as how to carry on the work of organisation and negotiation with employers. Thus arose in the movement the phenomenon of outsiders. Most of these outsiders came from political parties.

In the worlds of Srivastava, “becoming leaders of trade unions —became a fashion among the politicians of the country. Persons with little knowledge of the back-ground of labour problems — became the self-appointed custodians of the welfare of the workers.”

No wonder, they devoted more time and attention to political work as well as to the building up of their own leadership than to the problems of labour.

These outsiders also brought along with them the politics of their parties and this led to the division of unions on political lines. Each political party tried to have its own union and its own central organisation.

Accordingly, there were Congress unions, communist unions and socialist unions in each trade and industry and, at times, even in the individual plants. Employers often took advantage of this division in labour ranks and played off one union against another.

Another cause was the financial weakness of the unions. In 1953-54, average annual income of a union amounted to Rs. 1906 only. The reason was that their membership fee was small. Even that was not regularly collected.

A large number of members usually remained in arrears for long periods and paid only when a struggle was impending or when there was an individual grievance to be redressed. This defect was sought to be rectified by the amendment passed in 1960 under which a minimum subscription fee of Re. 0.25 per month per member was prescribed.

Due to financial difficulties, many unions could not appoint full time cadre of workers or maintain an office, much less undertake any welfare work.

It is interesting, in this connection, to note that, in 1949-50, a single union, namely the Ahmedabad Textile Labour Association, accounted for 80% of the total expenditure incurred by all unions on welfare work. On an average, a union spent only 6.2% of its income on educational and welfare activities.

The biggest difficulty, especially in the early period, in the growth of the unions was the opposition of employers. Many employers regarded the formation of union as an act of disloyalty and treachery which was rewarded with assaults on workers, victimisation and blacklisting.

Often bribery and intimidation were used to crush the movement. The attitude changed after independence but there were still many employers who believed in “starving the workers into submission.”

Yet another impediment was the attitude of the government. In earlier years, workers’ attempt to hold meetings or organise demonstrations or strikes was regarded as act of treason and, therefore, suppressed with great force. Policy did change after independence but even so, employers often managed to secure state help in order to crush the labour.

The practice of referring industrial disputes to adjudication developed during the war and continued even since, discouraged negotiation and collective bargaining with the employers. This not only deprived the unions of their main work but also encouraged the tendency towards seeking relief through courts.

Unions became lawyer’s offices and both workers and employers began to seek outside help to settle disputes. This naturally affected the growth and influence of trade unions adversely.

These are some of the problems that the movement had to face. It developed and grew despite the difficulties posed by these problems. By dint of a hard and long struggle, the movement succeeded at last in securing an assured place in the society, employers and the government both having realised that it was impossible to stop its growth and further that it can be of value in the economic development of the country.

3. Essay on the Industrial Disputes in India:

Before the First World War, industrial disputes were not very common in India although strikes, rather loosely organised, did occur during the early phase of industrialisation. As early as 1859-60, a notable scuffe took place between the European railway contractors and their Indian workers.

There is record of a strike over wages at Empress Mills, Nagpur in 1877. According to R.K. Dass, between 1882-90, as many as 25 strikes took place in the Bombay and Madras mills.

The frequency of strikes, however, increased after 1905 firstly because of the introduction of electricity which made it possible for mills to work longer hours and, secondly, because of the growing nationalism which created a new political awakening among workers. There was a wave of strikes —in the Bombay mills, on the railways, in the railway workshops and in the government press at Calcutta.

The highest point was reached with the six-day political mass strike in Bombay against the sentence of 6 years’ imprisonment on Tilak in 1908. These strikes notwithstanding, the period before the war was relatively free from strikes as the workers lacked organisation and leadership, had an entirely passive outlook on life and regarded return to their village as the only remedy against the hardships of industrial life.

The war of 1914-18 greatly changed the position and since the end of it, the relations between the workers and their employers became much more strained. The war had raised the cost of living; capitalists had reaped a rich harvest of profits and the workers wanted their share.

The Jallianwala Bagh incident, the repressive measures of the government like the Rowlatt Act and Martial Law, the non-cooperation movement, all created mass awakening among the working class.

The result was a strike-wave of overwhelming intensity. The end of 1918 saw the first great strike affecting the entire cotton industry in Bombay. By January 1919, 1,25,000 workers covering practically all the mills were out. In 1920, nearly 200 strikes occurred up and down the country, not a few being protracted involving the general public in considerable inconvenience.

After 1922, the economic causes began to subside. Prices settled down and wages had been revised in accordance with the cost of living. At the same time, while political agitation lost in strength, the trade depression put the employers in a stronger bargaining position as they no longer had the same fear of temporary stoppage of work.

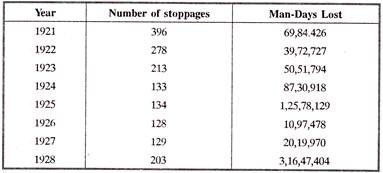

The strike fever, therefore, declined for some years and the number of stoppages came down from 396 in 1921 to 129 in 1927.

Of the strikes which occurred since 1918, one of the most serious was in the cotton mill industry in Bombay city in 1924; it involved over 1,60,000 workers and caused a loss of 7.75 million working days. The immediate cause of the trouble was the decision of the Mill owners’ Association to with-hold the annual bonus which had been granted for 5 years and which had become part of the wages.

A further strike against the reduction of dearness allowance broke out in September, 1925. The mill owners restored the cut but not before the strike had caused as loss of about 12 million working days. The year 1928 saw the greatest tide of working class activity in the post-war years, the number of disputes having jumped to 203.

A strike broke out in Bombay initially against measures of rationalisation and a 7 ½ % wage cut but later extended to a wide series of demands. This strike, involving 1,50,000 workers, lasted for six months. After every attempt to break the strike had failed, the government appointed the Fawcett Committee which recommended the withdrawal of the wage-cut and also conceded certain other demands of the workers.

In 1929, though the overall situation had become less acute, another general strike of Bombay textile workers broke out under the leadership of the Girni Kamgar Union. While the strike of 1928 was directed against rationalisation, that of 1929 was against victimisation of workers connected with the earlier industrial disputes.

This strike is of interest for two reasons. First, it was in this strike that the communist group made its influence fell. Second, this strike paved the way to the enactment of the Trade Disputes Act, 1929. The strike lasted for 6-7 months and workers in all the cotton mills of the city participated.

A similar general strike, which occurred in 1929 in the Bengal jute mills, was directed against the employer’s decision to increase the working hours from 55 to 60 per week. The strike lasted for 11 weeks, involved 2,72,000 workers and was withdrawn only after most of the demands were accepted by the employers.

The period 1929-36 was one of, comparatively speaking, industrial peace. The number of disputes came down from 203 in 1928 to 118 in 1932 and 161 in 1936. The reason was that the Depression had increased the bargaining position of the employers. Moreover, the Meerut conspiracy had dealt a severe blow to labour leadership and also terrified the workers. The movement had also been weakened by the split in its ranks.

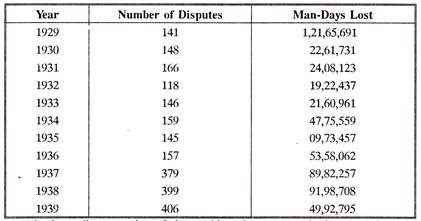

The number of disputes suddenly rose to 379 in 1937 and these involved a loss of 9 million man-days. This sudden spurt in work stoppages may be explained by the advent, in 1937of popular Congress ministries in the provinces which aroused the expectations of the workers. Genuine economic difficulties of the workers and the intransigence of the employers were the other two contributory factors.

The immediate reaction of the working class towards the Second World War was in the form of an anti-war strike in October, 1939 in which 90,000 workers struck work. In March 1940, with the sharp increase in the cost of living, 1,75,000 textile workers in Bombay resorted to a strike in support of their demand for dearness allowance.

In the trail of the Bombay strike came a wave of strikes of textile workers of Kanpur, municipal workers in Calcutta, jute workers of Bengal and Bihar, oil workers of Digboi, coal miners of Dhanbad and Jharia, Iron and steel workers of Jamshedpur —all demanding an increase in dearness allowance.

The government met the situation by promulgating the Defence of India Rules which made strikes illegal in many essential industries while, in others fourteen days’ notice was required before a strike or lock-out could be declared.

There was, therefore, a decline in the number of disputes from 406 in 1939 to 322 in 1940. The workers of public utility services like Railways and Posts and Telegraph, where strikes were totally prohibited, suffered. There was no increase in wages except a small D.A. but they could not protest.

As the war came to a close and restrictions placed on the workers were withdrawn, the fire that was smouldering in their hearts burst forth. The situation was worsened due to demobilization of a large number of soldiers, sailors and civilian employees of the Defence Department. Further, a number of establishments, which had been set up during the war years, closed down as war orders terminated.

The trial of the I.N.A. soldiers and the Mutiny of the Indian sailors gave moral support to the aspirations of the workers. The result was an epidemic of strikes all over the country. This may be seen from the fact that in 1946 and 1947, there were 1629 and 1811 industrial disputes involving a loss of 12.7 million and 16.8 million man-days in 1945.

The Government intervened to secure an Industrial Truce Agreement in December, 1947, an upward revision of wages including dearness allowance and a share in profits.

At the same time, the machinery for the settlement of disputes was made more effective and, through conciliation and compulsory arbitration, many a dispute was settled. This led to decline in the number of disputes to 920 involving a loss of 6.6 million working days in 1949.

Stoppages further came down to 814 in 1950 although, due to the protracted strike in the cotton mill industry, the number of man-days lost was very high.

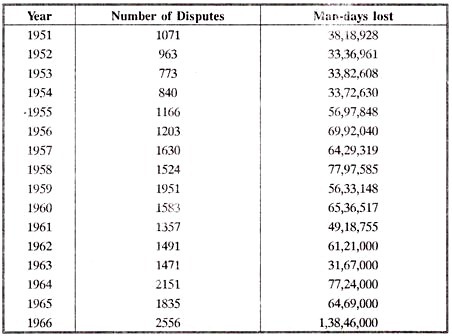

The situation again deteriorated towards the last year of the first plan. The year 1955 is particularly significant because of the textile general strike at Kanpur over the issue of rationalisation in which all trade unions participated and which resulted in a loss 16,93,747 man-days.

In 1956, there were strikes in Bombay, Ahmedabad and Calcutta against the reorganization of states over and above the strikes in collieries and certain defence establishments.

The overall picture of earnings of factory hands at the end of the first plan was not very hopeful to warrant any change in the attitude of the working class towards economic development. No doubt, average earnings had slightly increased but it was much too small to compensate for the rise in the cost of living. There was, therefore, a country wide demand for wage increase.

A new high was reached in 1957 when a record number of 1630 disputes took place. Alarmed at the situation, the government enforced an 8-point code of discipline and conduct, which brought down the man-days lost perceptibly down in 1961.

The situation was further improved by the Industrial Truce Resolution adopted immediately after the declaration of emergency in October 1962, appointment of Wage Boards and increased reliance on tripartite discussion and consultations to settle disputes.

The number of disputes remained stable in 1962 and 1963 but the situation deteriorated in 1964 and became worse in 1966. The fervour caused by the Chinese aggression had cooled down while the decision taken, in its wake, to carry on both defence and development implied heavy deficit financing.

Similar resort to deficit-financing followed the conflict with Pakistan in 1965. The inevitable inflationary rise in prices was accentuated by drought in 1965-66, suspension of foreign aid and devaluation. No wonder, the number of disputes reached the record level of 2556 involving a loss of 13.8 million man-days in 1966.

Industry-wise, manufacturing accounted for the largest number of disputes. R.K. Mukerjee has estimated that of all the disputes that took place between 1921-41, 52% were accounted for by manufacturing industries, 2.6% by railways including railway workshops, 5.2% by engineering workshops and over 37% of the disputes occurred in miscellaneous establishments.

The picture was not different in 1966 when 66.1% of the disputes took place in manufacturing, 17% in fishing and forestry, 4.8% in Transport and communications and only 3.2% in mining and quarrying.

Causes of Disputes:

Factors responsible for industrial disputes were many. Some were just trivial. For instance, during 1920 — 22, strikes were called in a dozen collieries because “the simple Asansol miners were persuaded to believe that the elephants of a travelling show were the vanguard of Mr. Gandhi’s army.”

Broadly, however, the factors responsible for industrial disputes can be classified into four:

Economic:

The Royal Commission on labour was emphatic on one point that, “causes unconnected with industry play a smaller part in strikes than is frequently supposed—although workers may have been influenced by persons with nationalist, communist or commercial ends to serve, there has rarely been a strike of any importance which has not been entirely or largely due to economic reasons.”

These economic reasons may be summed up as those relating to wages, payment of bonus, dearness allowance, conditions of work and employment, working hours, unjust dismissals, leave, holidays with pay and delay implementing the awards of Tribunals. Rationalisation was another important issue on which labour feeling often ran high.

According to Joshi and Memoria, 49.7% of all industrial disputes between 1921 — 50 were caused by economic factors. In 1966, wages and allowances alone accounted for 35.8% all disputes. Victimisation was another cause industrial between 1921 — 50 were related to personnel i.e., reinstatement or dismissal of one or more individuals. Again in 1966, matters pertaining to personnel account for 21% of the disputes.

Political:

Among the non-economic causes, the most important was political. As early as 1908, there was a strike in Bombay against the sentence of 6 year’s imprisonment on Tilak. A number of such political strikes were conducted during the Khilafat, non-cooperation and civil Disobedience Movements.

Even in the post-independence period, political parties, particularly of the left, used the weapon of strike, especially in Bengal and Kerala, to pressurize the authorities. At time, trouble arose when employers refused to recognise a particular union on political grounds and, instead, preferred one belonging to a shade of opinion acceptable to them.

A typical instance is the big general strike in Kanpur in 1937, brought about by the non-recognition of the labour union — The Mazdoor Sabha. Similarly, 5000 workers of the premier automobiles, Bombay went on a 101 day strike in 1958, on account of the withdrawal of recognition of the union.

Moral:

Apart from a few who carried out certain welfare and amenity schemes for their employees, employers, by and large, failed to recognise the value of the human element in industry and their responsibility to provide proper working and living conditions. In the slums where workers were housed, “man was brutalized, womanhood dishonored and childhood poisoned at its very source.”

These appalling living conditions and the dark, dingy, poorly ventilated factories, in which they worked, were hardly conducive to good relation between the worker and the employer. True, under the Act of 1948, labour welfare officers were appointed in all factories employing 500 or more persons, but, as Charles Mayers explains, these officers were expected “to legalize the illegal actions or get out.”

Psychological:

A fundamental cause was psychological. During the course of his long struggle, the worker had acquired a new self-confidence; he was aware of his role and status in society and was jealous of his dignity. The employers, on the other hand, did not grasp the change and were, therefore, not prepared to change their attitudes.

They continued to be authoritarian in their approach and harsh-nay-inhuman, in their treatment of workers. They regarded trade union activity as an invasion of managerial rights.

This led the worker to believe that the strike was the only method to forcefully draw the attention of the employer to the justice of his demand. However risky to himself and harmful to the national good this course of action was, the worker appeared to be intellectually and emotionally conditioned to follow it.

4. Essay on the Machinery for the Settlement of Industrial Disputes:

The earliest legislation relating to the settlement of trade disputes was the Employers and workmen (Disputes) Act of 1860 which was applicable to the construction of railways, canals and other public works and provided for summary disposal of disputes by Magistrates.

Besides being limited in its application, the Act contained the undesirable feature of regarding any breach of contract on the part of the workers as criminal offence.

It was only after the I world war that labour movement gathered strength and eventually the government came to hold the view that “the growth of trade unions in the country is likely to render legislative measures for the investigation and settlement of trade disputes at once more necessary and more easy of applications.”

This realisation as also the increase in the number of industrial disputes ultimately led to the passing of the Trade Disputes Act, 1929.

The Act provided for the setting up of courts of Enquiry or Boards of conciliation. The Court of Enquiry was to enquire into the specific matters referred to and submit a report while the Board of conciliation was to endeavour to bring about a settlement within a reasonable period of time.

In case of failure, the board was to send a full report along with findings and recommendations to the appointing authority. Sympathetic strikes were declared illegal and provision was made for at least fourteen days notice for strike or lock out in public utility services.

The Act suffered from many limitations. For example, it did not provide for any machinery for the prevention of industrial disputes. The courts of enquiry or the boards of conciliation were not permanent bodies.

Appointed on ad hoc basis, they could neither keep in touch with day to day developments in the industry nor take a long term view of the problem. What is more, the act was seldom used for relating with industrial unrest.

For example, between 1929 —1933, there were more than 500 disputes but only two courts of enquiry and two boards of conciliation were appointed. It is only after the formation of congress ministers in the provinces that increasing use began to be made of these bodies with remarkable results.

The Act of 1929 was amended in 1932,1934 and 1938. The last amendment provided for the appointment of conciliation officers who were charged with the duly of mediating in or promoting the settlement of disputes.

In 1938 was also passed the Bombay Industrial Disputes Act which, apart from classifying the union into registered, qualified, and representative, also provided for three distinct steps before a strike or lock-out could be declared. First was the serving of a notice followed by negotiations. The agreement reached, the contending party had to submit a full statement of its case.

The dispute was recorded and the chief conciliator submitted a report to the government. Finally, in case of failure, the government could refer the dispute to a board of conciliation. During the period of conciliation, strikes and lock-outs were declared illegal. So far, conciliation was not obligatory but now it was made compulsory.

The Bombay Industrial Disputes Act of 1938 was a pioneer legislation radically different from the previous legislation on the subject. It marked the beginning of a labour judiciary with its provisions for the creation of a permanent machinery in the shape of an industrial court.

It was criticised on the ground of introducing heavy penalties for illegal strike, compulsory conciliation, and also for the official character of the conciliation machinery. Subsequent experience, however, showed that most of the objections were political.

War-time exigencies carried the country further along the road to compulsory arbitration and greater intervention of the state in the shaping of industrial relations.

Under rule 81A of the Defence of India Rules, Government assumed power to:

(a) Prohibit strikes and lock-outs;

(b) To refer a trade dispute for conciliation or adjudication and

(c) To enforce the decision of the adjudication authority. This, in effect, meant compulsory arbitration.

In practice, however, these rules were not strictly enforced. The government chose neither to punish the labour leaders nor to prescribe fair wage and fair conditions of work and employment for which it had assumed powers. Strikes, therefore, continued to be declared with impunity.

Official attitude had changed in the direction of a more active role for the govt. even before independence. Independence hastened the process and so radically altered the tone and content of govt. policy as to usher in a new phase in development of industrial relations in India. Conditions on the labour front were extremely unsatisfactory.

Real earnings of industrial workers had declined and labour organisations were very militant. The total number of workers involved in industrial disputes reached a new high while industrial production declined substantially from its war-time peak. Additional problem were created by inflationary pressures, bottlenecks in transportation, foreign exchange and in the critical area of food supplies.

The partition of the country imposed another serious strain on its economy. It was under such circumstances that the govt. announced, early in 1947, the five-year labour programme in which it promised improvement of the conditions of recruitment and tenure of workers, added benefits of social security and a better wage structure including promotion of ‘fair-wage’ agreements.

Rule 81-A was also replaced by the industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

The Act provided for the setting up of works committees, the appointment of conciliation officers, conciliation boards, courts of enquiry and also for permanent industrial tribunals. The works committees, comprising equal representatives both of employers and workers, were expected to remove day to day differences by mutual discussions.

Conciliation officers and conciliation boards were designed to promote settlement between contending parties. If such efforts failed and both parties applied, the dispute could be referred to an industrial tribunal. The govt. assumed powers to enforce the decision of such tribunals, either wholly or partly, for such periods as it deemed necessary.

A difficulty soon arose because, in the absence of well defined principles, several tribunals expressed divergent views on various issues referred to them. This created anomalies which led to discontentment both among employers and employees. The Industrial Disputes (Appellate Tribunal) Act, passed in 1950, sought to rectify this situation.

This Act provided for the setting up of a labour Appellate Tribunal to hear appeals against any award or decision of an adjudicating authority in matters pertaining to finance, wages bonus, retrenchment of staff and questions of law.

With the introduction of planning in the country, there was a perceptible change in the attitude of the govt. Speaking at the Tripat labour conference held in 1952 at Nainital Mr. V.V. Giri then the Labour Minister, declared that direct negotiations and collective bargaining were preferable to compulsory arbitration.

In his own words, compulsory arbitration. In his own words, compulsory arbitration “stands……. as a police man looking out for signs of discontent and at the earliest provocation takes the parties to the court for a dose of costly and not wholly satisfactory justice.”

All major unions, though opposed to the ‘Giri Approach’ were also highly critical of the inordinate delays which accompanied the adjudication process. The Appellate Tribunal, which had reversed or modified many of the decisions of the lower tribunals, was the special target of attack. In sympathy with this demand, the govt. passed the Industrial Disputes (Amendment and Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1956.

The new Act provided for a three-tier system consisting of:

(a) Labour courts to hear cases relating to standing orders, discharge or dismissal of employees and other disciplinary action;

(b) Industrial Tribunals to hear disputes over wages, allowances, hours, leave, bonus and rationalisation;

(c) National Tribunal to decide disputes likely to affect establishments situated in more than one State.

The Act enlarged the definition of workman, abolished the system of appeals and enhanced penalties for failure to implement awards. More liberal provision was also made for lay-offs and for retrenchment. The Act, as amended in 1957 did not satisfy labour.

The worst feature of the Act was the power it gave to govt. to modify an industrial award. This hindered early settlement because the parties, realising the ultimate power of the govt. to alter the award, never placed all their cards on the table. Furthermore, the Act did not give effect to the scheme of collective bargaining as envisaged by Mr. Giri.

In view of a fresh wave of labour unrest and the paramount need of maintaining the tempo of industrial production under the second plan, the govt. made yet another effort to secure space.

In 1957, the standing labour committee of the Indian Labour Conference adopted a “code of industrial Discipline” which bound the employers and employees to settle all their disputes by mutual negotiations, conciliation and voluntary arbitration.

The aim was to eliminate all forms of coercions, intimidation and violence in industrial relations. This code is important in so far as it symbolizes govt’s policy to promote, on a voluntary basis, industrial peace with the help and cooperation of employers and workers.

The ‘Industrial Truce’, accepted in the wake of the Chinese aggression, further bound the parties to eliminate work stoppages, improve production and reduce costs.

Broadly speaking, the industrial relations policy of the govt. might have fulfilled the purpose of settling disputes and, to an extent, in avoiding work stoppages, but it did not quite succeed in achieving the positive task of creating the necessary atmosphere, institutions and procedures for good and harmonious labour — management relations.

This failure was largely due to the undue emphasis on compulsory adjudication and the comparative neglect of collective bargaining.

Labour Legislation:

The development of modern factories, transport, and plantations, during the second half of the 19th century, led to a ruthless exploitation of the working class. The worst features were the long how put in by the mill-hands a day, or 80½ hours a week in the cold weather and 14 hours a day or 98 hours a week in the hot weather.

With the introduction of electricity in 1887, the daily working hours were further extended and ranged from 12½ to 16 in different localities; the worst sufferers being the weavers in Calcutta jute mills who work 1 for 15-16 hours.

There was no regular system of rest period to mitigate the harshness of such long periods of work. Some factory owners did provide a rest interval but it was wholly inadequate as it lasted only for 15-30 minutes; others “made no stops but expected their hands to eat while tending their machines.”

Nor was such hard toil relieved by regular days of rest or holidays. The Bombay Factory Labour Commission (1885) found that, on an average, Indian factories gave 15 holidays a year as against 88 holidays that an English factory hand enjoyed.

The result was the complete physical exhaustion of the workers who sometimes fell fast asleep on the mill floor directly after their work was over and even before some of their fellow workers were able to get out of the mill doors.

A feature of this ruthless exploitation was that women and children also were made to work the same long hours as men.

The Bombay Factory Labour Commission (1885) found that in the cotton ginning factories employing mostly female and child labour, the usual working hours were from 4 or 5 A.M. to 8 or 9 P.M. and, when working at high pressure, they worked sometimes day and night for eight days consecutively until the hands were tired out and lost their health.

Surprisingly enough, the first impulse towards legislative action to mitigate the harshness of these evils of capitalist industrialism in India came, not from India, but from England whose philanthropists and textile manufacturers joined hands to demand statutory protection for the health of the women and children employed in factories.

The clamour in Britain for factory legislation in India found support among Indian philanthropists also, the most prominent being Sorabji Shahpurji Bangali. Simultaneously, there were faint stirrings within the working class.

In December 1879, Rughaba Succaram, who was himself a worker, submitted a memorial to the Govt., signed by 578 workers and requesting for a working day of 9 hours and a weekly holiday. It was in consequence of this agitation, both in India and England, that the govt. passed the Indian Factory Act, 1881.

The Act of 1881:

The Indian Factories Act, 1881, fixed the minimum age of employment for children at 7 years, maximum hours of work at 9 per day with a rest interval of one hour and four holidays in a month. The Act also provided for proper fencing of dangerous machinery and prompt reporting of accidents.

It was, however, applicable only to factories utilizing mechanical power, employing 100 or more persons, and working for more than four months in a year. What is more, it specifically excluded Indigo factories, tea and coffee plantations from its operations.

Significantly, the hours of work of men and women were also left unregulated. The Indian Factories Act, 1881 was quite elementary and, for all practical purposes, quite ‘innocuous’.

The inadequacy of the Act gave rise to further agitation for its amendment. The Lancashire manufacturers, in particular, demanded the application of the more stringent English factory legislation in India. The question was repeatedly raised both inside and outside the British Parliament.

A new element was that the workers themselves held meetings demanding restricted hours of work with suitable rest interval, weekly holiday and timely payment of wages.

A memorial signed by 5,500 mill workers was presented to the Bombay Government. The decisions of the International Labour Conference, held at Berlin in March 1890, gave an added fillip to their agitation. Torn between pressures and counter- pressures, the government finally passed the Indian Factories (Amendment) Act, 1891.

The Act of 1891:

The Act of 1891 applied to factories using power, employing 50 or more persons and working for 120 days or more in a year. It provided for a weekly holiday and a mid —day break of half an hour for all workers. Working hours for women were fixed at 11 per day including 1½ hours break for rest.

They were not to work at night except in factories of Bengal working on a shift basis. The minimum age for children was raised to 9 years and their hours of work were restricted to 7 per day.

Once again, the smaller and seasonal factories, in which prevailed some of the worst abuses of the factory system, escaped the reach of legislation. Nor were the demands of Indian philanthropists and workers for a uniform 11 hours- day, compensation for accidents, and medical aid in case of sickness accepted.

The system of factory inspection also continued to be defective with the result that the provisions of the Factory Act were systematically evaded. Understandably, the powerful Lancashire interests remained dissatisfied and they continued a vigorous agitation for a more comprehensive legislation.

The Act of 1911:

The result was the passing of the Indian Factories Act of 1911. Under this act, daily hours of work of women and children in non-textile factories were kept unaltered at 11 and 7 respectively, but in textile factories, Children’s workload was reduced to six per day and that of adults, male or female, was fixed at not more than 12 hours per day.

The Act totally prohibited night work for all women except those working in ginning mills. It also provided for ½ hour’s rest interval after every six hours of continuous work; obliged children to produce certificates of age and fitness before employment; and also imposed stricter regulations with regard to ventilation, lighting, drinking water and dancing of machinery etc.

No further change in factory law was introduced until 1922 when the factory Act was amended to incorporate the draft conventions passed by the Inter-national Labour Conference held at Washington.

The Act of 1922:

The Act of 1922 extended the definition of ‘Factory’ to include all power-using establishments employing regularly not less than 20 workers. Local governments were, however, empowered to extend it to establishments employing not less than 10 persons irrespective of whether power was used or not.

The Act of 1922 raised the age of employment to 12 years; restricted the work-load of children between 12—15 years of age not more than six hours; restricted the work-load of all adults to 11 hours per day or 60 per week, with a rest-interval of 1/2 hot after every six hours of work and a regular weekly holiday.

The Act further provided that no woman was to work in a factory between 7 P.M. to 5.30 A.M. The Act of 1922 was amended in 1923 —1926, and 1931 to remove certain administrative difficulties and to make certain minor improvements.

In 1923, a small defect relating to weekly holidays was removed while the amendment, made in 1931, repealed the Act of 1860 under which workers were liable to criminal liabilities for breach of contract.

The Act of 1934:

On the recommendations of the Royal Commission on labour, appointed in 1928, was passed the Factories Act, 1934. The Act classified the factories into two, seasonal and non-seasonal.

The hours of work in non-seasonal factory were fixed at 10 per day or 54 per week and at 11 per day or 60 per week in seasonal factories. The hours of work for children in the age-group of 12-15 years were fixed at 5 per day in both seasonal and non-seasonal factories.

Overtime was required to be paid at the rate of 1½ times the ordinary wages. All persons between 15—17 years were called “adolescents.” They were to be treated as children unless medically certified lit for adult work.

A number of provisions about welfare activities, fencing of machinery, safety devices, humidification were also made. The administration of the Act was made the responsibility of the provincial governments who appointed inspectors for the purpose.

The Act of 1934 was amended several times. The amendment made in 1946 was an important one in so far as it introduced the principle of 48 hours a week. Experience of the working of the 1934 Act revealed a number of defects which hampered its effective administration.

Further, the provisions for safety, health and welfare of the workers were found to be inadequate and such protection as the Act provided did not extend to a large mass of workers employed in small work places. The need was, therefore, felt for a thorough overhaul of the existing legislation. Accordingly, the Indian Factories Act was passed in September, 1948.

The Act of 1948:

The Indian Factories Act, 1948, was a comprehensive piece of legislation which applied to establishments employing 10 or more workers where power was used and 20 or more workers where power was not used.