Many years ago economists pondered over the implication of varying the proportion in which the factors were combined and came up with a principle which has become famous as the Law of Diminishing Returns. They applied this law to agriculture but it holds true for all kinds of production. The operation of the law may be explained by means of a simple arithmetical example.

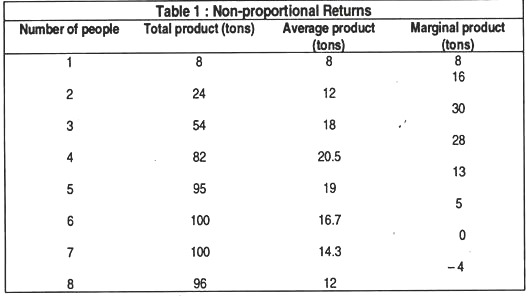

Let us assume that some particular crop is to be grown on a fixed areas of land, say 20 acres. We also assume that the amount of capital to be used is also fixed in supply. Labour is the only variable factor. Table 1 sets out some hypothetical results obtained by varying the amount of labour employed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The above table is based on the following assumptions:

1. Labour is the only variable factor.

2. All units of the variable factor are equally efficient.

3. There are no changes in the techniques of production.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the basis of these assumptions, we can conclude that any changes in productivity arising from variations in the number of people employed are due entirely to changes in the proportions in which labour is combined with the other factors.

Illustration:

Table 1 illustrates the Law of Diminishing Returns (or the Law of Variable Proportions) which states that as we add successive units of one factor to fixed amounts of other factors the increments in total output will at first rise and then decline.

Columns 1 and 2 of Table 1:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They show the total products at different levels of employment. Average product (or output per worker) is shown in column 3 and is obtained by using the formula.

Total product/Number of workers = Average product

Marginal product, shown in column 4, describes the changes in total output brought about by varying employment by one person. The addition of a third person adds 30 tons to total output while the employment of a fourth person increases total output by 28 tons.

Returns to the variable factor:

Since labour is the only variable factor, changes in output are related directly to changes in its employment. So, we can speak of changes in the productivity of labour or changes in the returns to labour. As the number of people increases from 1 to 6, total output continues to increase, but this is not true of average product (AP) and the marginal product (MP).

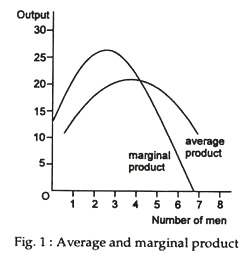

As more people are employed, both the AP and the MP begin to rise, reach a maximum and start to fall. These movements are clearly seen in Fig. 1. As the number of people increases from 1 to 3 the marginal product of labour is increasing. Up to this point the fixed factors are being under utilised.

When the number of people employed exceeds 3, the marginal product of labour begins to fall — an indication that the proportions between the fixed and variable factors are becoming less favourable. Marginal product begins to fall before average product and we get the maximum average product of labour when 4 people are employed.

If we now wish to increase output and maintain the same productivity of labour, it is obvious that an increase in the fixed factors must accompany the increase in the variable factors. This would require a change of scale of production or an increase of the size of the firm and is possible only in the long run.

It is this feature of increasing production and falling productivity which is highlighted by the Law of Diminishing Returns. In Table 1 we see that diminishing marginal returns set in after the employment of the third person and diminishing average returns after the employment of the fourth person. Here, the marginal productivity of the seventh person is zero — his employment does not change total output.

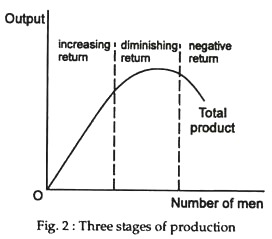

Fig. 2 makes use of the total product curve and provides another view of the relationship between employment and output where some of the factors are fixed in supply.

The law of diminishing returns states that as more and more resources are allocated to a fixed asset, then eventually output will diminish.

We can summarise the possible effects of increasing the quantity of a variable factor as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Increasing returns — total product increases at an increasing rate (MP is increasing).

2. Diminishing returns — total product is increasing at a decreasing rate (MP is falling).

3. Negative returns — total product is falling (MP is negative).

Causes of diminishing returns:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the short run diminishing returns appear whenever a firm operate above capacity. The average cost curve is U-shaped. The bottom of the U is the point of least cost. When a firm produces more than the least cost output it is on the rising part of the U and is operating under diminishing returns.

In the long run, diminishing returns may appear for any of the following reasons:

1. Scarcity of productive resources:

If increased supply of a particular article, essential to production, cannot be obtained, long-run reorganisations of a firm will have to be based on a limited supply of that resource. Agriculture is based on land, the supply of which is more or less fixed. Expansion of agricultural production involves the use of more capital and labour with relatively less land.

Marginal returns therefore diminish. The principle applies to manufacturing industries when the supply of an essential item (e.g., a particular raw material or a particular machine) is scarce. Scarcity of productive resources may be due to shortage of supply or to high costs of transfer from one use to another.

2. Operation of the principle of variable proportions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the quantities or the proportions of the factors are altered, output and the technological costs of production will change. The Law of Variable Proportions gives us a simple rule about how the costs will vary.

The rule is that if all the factors are increased simultaneously and in suitable proportions, the total output will generally increase more than proportionately and the cost of production will fall. But, if one of the factors is kept constant while the others are increased, then output will not increase in proportion and hence the cost of production will increase.

3. The cost of entry:

Starting a new production Unit is not always easy. When new entry is difficult, increase in output must come from the existing firms who will be forced to go beyond the optimum size. This will cause both average costs and marginal costs to rise.

Proof of the Law:

The law is simply a generalisation based on experience. If the law were not true, a cultivator could have doubled or trebled his output level by just doubling or trebling the amount of labour and capital on the same plot of land. Had it been so, one plot of cultivated land could have produced food for millions of people; but this is absurd.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Past experiences of the farmers prove conclusively that the law must operate in the long run. For this reason, Paul Samuelson observes, “The law of diminishing returns is an important, often-observed economic and technical regularity”.

Assumptions of the Law:

The law of diminishing marginal returns, though ‘a fundamental law of economics and technology’, is based on the following important assumptions:

(a) Application of more labour and capital on a fixed plot of land,

(b) Optimum utilisation of the land with the required number of labour and capital, and

(c) No improvement in the farm technology.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Limitation of the Law:

The law of diminishing marginal returns is “not universally valid”.

It does not operate in the following circumstances:

1. Under-utilisation of land:

The application of more labour and capital on a particular plot of land may cause the marginal product to rise if the land is not utilised fully. Beyond the point of full utilisation any increase in labour and capital usage would cause the marginal product to fall.

2. Improvement in the method of farming:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The law would not operate for the time being if there is an improvement in the farming methods due to an invention of a new type of farm equipment.

It is to be noted that the law may not operate in the short run because of the reasons stated above, but experience has demonstrated that the law must operate ultimately. For this reason, the law is known as the Law of Eventually Diminishing Marginal Returns.

Where does the Law apply?

It is important to note that, the law of variable proportions (or diminishing returns) is equally applicable to land and capital and, no doubt, to entrepreneurship. The marginal and average productivity of capital will, at some point, start to decline as more and more capital is applied to a fixed supply of land and labour. The same will apply to the productivity of land when more and more land is combined with a fixed amount of labour and capital.

The law of diminishing returns applies in all cases where the supply of a factor of production is kept constant while the other factors increase. In agriculture, since the supply of land is more or less fixed, the law applies.

In mining the law applies in particular cases. A mine is worked only so long as the deposits last. When these are exhausted the return falls to zero. The yield of different mines vary so much that we cannot lay down a general law regarding any mining industry as a whole. The same considerations apply to fisheries.

In the case of building sites, it is generally agreed that the law applies. The returns from the upper stories of a house gradually decrease with the height, while the costs of construction increase.

In manufacturing industries, the law usually applies in the short period, i.e., when output is increased without increasing the fixed capital equipment.

Conclusion:

The law of diminishing returns only applies when other things remain equal. The efficiency of the other factors and the techniques of production are assumed to remain constant. Now, we know that these other things do not remain constant and improvements in technical knowledge have tended to offset the effects of the law of diminishing returns. Improved methods of production increase the productivity of the factors of production and move the AP and MP curves upwards.

But, this does not mean that the law no longer applies. It is still true that in the short period (when other things can change very little) increments in the variable factors will at some point yield increments in output which are less than proportionate. In some developing countries like India, where there is little or no change in the technique of production and population is increasing, we can see the law of diminishing returns operating only too clearly.