Samuelson’s Multiplier Accelerator Interaction Model!

The principle of acceleration working by itself is perhaps not much forceful but recently it has attained more importance in the trade cycle theory by its alliance with the multiplier principle. Professor Samuelson has built a model of multiplier- accelerator interaction. He could show that the interaction of the accelerator with the multiplier is capable, under certain circumstances, of generating continuous cyclical fluctuations.

After P. A. Samuelson, J. R. Hicks, R. F. Harrod and A. Hansen have made fairly successful attempts to integrate the two concepts and thus introduced remarkable improvements in the theory of economic growth. It is, therefore, quite interesting and useful to analyse the combined (leverage) effects of multiplier and accelerator on national income propagation. The combined effects of autonomous and induced investment are expressed in what Hansen called the Super-Multiplier.

Paul Samuelson has derived the super multiplier as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Yt = Ct + It ….(1)

Income in period t equals the consumption in period t – 1 plus investment in period t

Yt = bYt-1+ lt ….(2)

where b is the MPC in period t – 1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Investment in period t is partly autonomous (Ia) and partly induced (Id). The induced investment depends upon changes in consumption which in turn depend upon changes in income. Therefore, we can express as

It =la+Id

= Ia+V(Ct-Ct–1)

= Ia +V{bYt-1-bYt-2}

ADVERTISEMENTS:

=Ia + V.b(Yt-1-Yt-2)….(3)

The expression in equation (3) tells us that changes in net investment and hence income for period t can be estimated as a weighted sum, the weights being the values of b (MFC) and V(the output-capital ratio). Professor J.R. Hicks has called the joint action of b and V as the super multiplier and used it to build up his theory of the trade cycle.

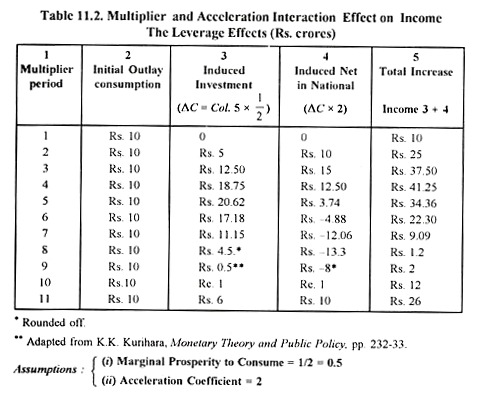

That is, the speed with which income increases as a result of accelerator- multiplier interaction depends inversely on the marginal propensity to save and directly on the value of the acceleration coefficient. The lower is the MPS and the higher is the value of the accelerator, the greater the speed with which changes in net investment are multiplied into changes in income. We show the working of the super-multiplier through the Table 11.2 given hereunder.

The Interaction:

In the Table 11.2 given below, we can easily see the process of income propagation through the multiplier and acceleration interaction. We assume that

(i) MPC = ½

(ii) Acceleration Coefficient = 2.

In the first period there is an initial outlay of Rs. 10 crores, which does not lead to any induced investment. Hence, the total rise in national income in the first period is Rs. 10 crores (being equal to the initial outlay of Rs. 10 crores).

Since the MPC =1/2, induced consumption in the second period is Rs. 5 crores (shown in the column 3) and the acceleration coefficient being 2, the induced investment in the second period is Rs. 10 crores, (shown in column 4) and the total leverage effect (total increase in national income) is Rs. 25 crores (shown in column 5).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, in the third period we get increased consumption of Rs. 12.50 crores and induced net investment of Rs. 15 crores (being the difference between 12.50 crores and 5 crores in column 3). Thus, total income in the fourth period has reached the peak level of Rs. 41.25 crores, as a result of the combined multiplier and acceleration effects i.e. through their interaction also called Super Multiplier. Then, in the fifth period, the marginal income increase starts falling off. It falls to rock bottom level of 1.2 crores in the 8th period and then again starts rising in the 9th period from 2 crores to 12 crores.

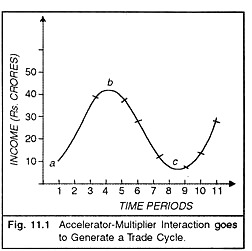

It goes up to 26 crores in the 11th period, thereby completing a cycle. If we go on calculating the multiplier-acceleration effects in the various columns we will find that the result is quite a moderate type of recurring cycle which repeats itself indefinitely. If we show the values of income and the time periods on a graph, we get a regular trade cycle m n shown in the figure given below.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This shows that an MPC of less than unity gives an answer to the crucial question: Why does the cumulative process come to an end before a complete collapse or before full employment? Hansen says that the rise in income progressively slows down on account of the fact that a large part of the increase in income in each successive period is not spent on consumption. This results in a decline in the volume of induced investment and when such a decline exceeds the increase in induced consumption, a decline in income sets in. “Thus, it is the marginal propensity to save which calls a halt to the expansion on top of the multiplier process.”

We have in our table above assumed constant values of multiplier and acceleration coefficients but in a dynamic economy they also vary cyclically. Thus, when we study the results of leverage effects or interaction of multiplier and acceleration coefficients as they vary cyclically, we find that the levels of income will be subject to various types of fluctuations depending on the values of the acceleration and the multiplier.

Professor Paul A. Samuelson attempted to combine different values of the multiplier and accelerator to analyse the nature of income streams generated by them. He found that four different types of fluctuations are obtained when the super multiplier with different values works.

The Different Types of Income Fluctuations:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

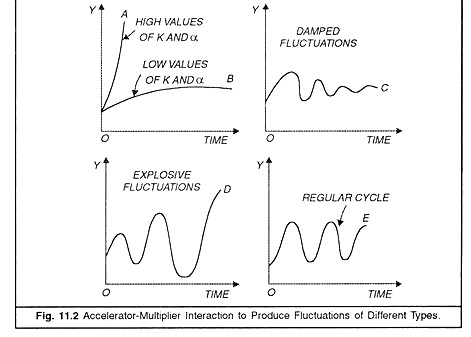

In the analysis of the process of multiplier accelerator working together, the values which we assume are of great importance. If the values of K and a are high, income would rise continuously at an ever-increasing rate, and there would be no downturn and therefore no cycle.

The path would be similar to curve A in Figure 11.2. At the opposite extreme, low values of the accelerator will also fail to generate a cycle; income will merely converge to the new equilibrium level which would have been achieved by the operation of the Multiplier alone, and will stay there; the accelerator will work to make income grow faster during the initial stage of expansion, but it will not be strong enough to alter the eventual outcome. Such a path of income is exemplified by curve B in Figure 11.2. If trade cycles are to be generated, it is necessary that the values of multiplier and accelerator lie between certain upper and lower extremes.

Three other distinct types of cycles may be generated according to the relative values of accelerator and multiplier. If accelerator is small relatively to Multiplier the oscillations would be ‘damped’—that is, they would become weaker and weaker and eventually die away altogether leaving income constant at its central value. Curve C in Figure 11.2 illustrates this kind of fluctuation. High values of Accelerator give rise to explosive fluctuations (Curve D), the cycles becoming stronger and stronger. The third type of cycle is a perfectly regular one exemplified by curve E where the cycle is regular as it is having equal periodicity and amplitude.

Samuelson’s Classification of the Regions of Different Cycles:

We have seen that multiplier and accelerator working together shape the process of income generation. But Professor P. A. Samuelson went farther and showed that with different combinations of the values of the multiplier and accelerator, it is possible to get income fluctuations (cycles) of various types.

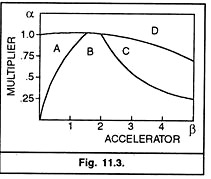

In a much-quoted article, Interaction Between the Multiplier Analysis and the Principle of Acceleration, (Reprinted in Readings in Business Cycle Theory, 1994), he showed that with different values of the Marginal Propensity to Consume on the one hand and the Accelerator on the other, it is possible from a continued injection of public investment, to get 5 different types of cycles or fluctuations. If we express MPC as a (Alpha) and acceleration coefficient as β (Beta), the five types of cyclical fluctuations which we can obtain are as follows.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Combination 1, α = 0.5 and β = 0. This gives us purely multiplier effects with income approaching the peak. Here the acceleration coefficient is zero (Region A in the Figure 11.3 below). This is the case of fluctuations having multiplier effects only, where income approaches asymptotic level.

Combination 2, α = 0.5, β=1. This gives us damped oscillations falling in value as they fluctuate about the multiplier level, gradually subsiding to that level. (Region B in the figure 11.3).

Combination 3, 0.5, (i= 2. This gives us regular or continuous cycles about the multiplier levelled more or less unchanged values repeating themselves indefinitely. (Region C).

Combination 4, α= 0.6 and/3 = 2. This gives us explosive cycles with variations about the multiplier level becoming larger and larger. (Region D in the diagram).

We summarise the above results. In Figure 11.3 above region A shows the multiplier effect only where the value of b (accelerator) is zero. In this case, with a constant level of public expenditure, the national income would reach its peak through multiplier only (i.e., 1/1-s) or 1/1-1/2 = 2.

Region B shows damped oscillations in value as they fluctuate about the multiplier level. Region C shows explosive cycles with variations about the multiplier level becoming larger and larger and region D shows the ever increasing national income approaching a compound rate of growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The essence of the argument is that multiplier-accelerator interaction is capable of generating various types of cycles and fluctuations: mild, damped and explosive. These cycles of fluctuations are of varying periodicity and amplitude. If we are able to find out the interacting values of the multiplier and accelerator in practice, we can ascertain for ourselves the nature of income fluctuations we are likely to experience in the absence of exogenous restraints. Professor JR. Hicks has used this mechanism for building up a theory of the trade cycle that explains the behaviour of business cycle around a rising trend of income.

Importance:

Thus, we find that the Super-Multiplier (interaction of multiplier and accelerator) assumes great importance in as much as it tends to speed up the rate at which the national income raises through the multiplier effects. In the first place, study of interaction of the two principles has paved the way for a more accurate analysis of the nature of the cyclical processes.

Further, an analysis of the interaction shows that it is possible to explain turning points in business cycle without resorting to special explanations. These factors are: a marginal propensity to consume of less than one plus the acceleration effect, the former being perhaps more important. The acceleration principle, before Keynes, was based on Say’s Law wherein increase in investment and a decrease in the rate of consumption would lead to a similar decline in investment—i.e., a cumulative expansion or contraction without limit.

Thus, the pre-Keynesian theory of acceleration gave an exaggerated picture of instability in the economy. But with the introduction of the concept of multiplier and consumption function, the long-sought-for limits to the fluctuations short of zero were at last found. Keynes’s concept of consumption function has brought forward the true significance of acceleration principle for business cycle analysis. According to Prof. K. Kurihara, “it is in conjunction with the multiplier analysis based on the concept of the marginal propensity to consume (being less than one) that the acceleration principle serves as a useful tool for business cycle analysis and as a helpful guide to business cycle policy.

Thirdly, it shows that it is a combination of the multiplier and the accelerator which seems to be capable of producing cyclical fluctuations. The multiplier alone produces no cycles from any given impulse. It only gradually increases income to a constant level as determined by the propensity to consume. But if the principle of Acceleration is also introduced, the result is a series of oscillations about what might be called the multiplier level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The accelerator at first carries total income above this level, but as the rate of increase of income diminishes; the accelerator induces a downturn which carries total income below the multiplier level, then up again, and so on. Professor J R. Hicks has used the accelerator multiplier interaction for building up a new theory of the trade cycle in this context.

Limitations:

A casual student of the super-multiplier (multiplier-acceleration principle) might feel that it is very easy to raise the economy out of the depths of depression simply by having a small increase in autonomous investment. This would stimulate consumption via the multiplier effects, which would then induce further investment and national income would continue to grow like a Topsy. Such a belief is a great illusion, however.

In actual practice, the interaction of multiplier and acceleration does not work for growth; at best, it is responsible for fluctuations on the path of movement of national income to higher and higher levels; that is, it does not work for growth; at best, it is responsible for fluctuations on the path of movement of national income from one level to another. The interaction, no doubt, shows significant cyclical effects but it has overlooked the other factors which work in the actual determination of the total income effect of the multiplier and acceleration principles.