Macro-Economic Effects and General Price Level!

1. The Wealth Effect:

Individuals and businesses hold money, bonds and other financial assets in their portfolio. In a world in which prices keep on changing the market value of these assets is one of the determinants of spending. It is a well known proposition of macro-economics that when the general price level rises, the value of money (or the purchasing power of money) falls.

This fall in the market value of assets leads to a decline in household and business spending. This is known as the wealth effect of a change in price, a phenomenon first discovered by A. C. Pigou, one of the followers of J. M. Keynes. The wealth effect may simply be stated as follows: a change in the general price level will cause a change in spending by changing the real value of wealth.

Don Patinkin has refined the concept and has given it a different name: the real-balance effect. Real values are those that have been adjusted for price level changes. Here real values indicates ‘purchasing power’ or, command over goods and services.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When the price level changes, there is an automatic change in the purchasing power of financial assets. To be more specific, when the general price level rises, there is an immediate rise in the real value of financial assets and stock of wealth. And this stimulates aggregate expenditure—consumption spending of households and investment spending of businesses.

2. The Interest Rate Effect:

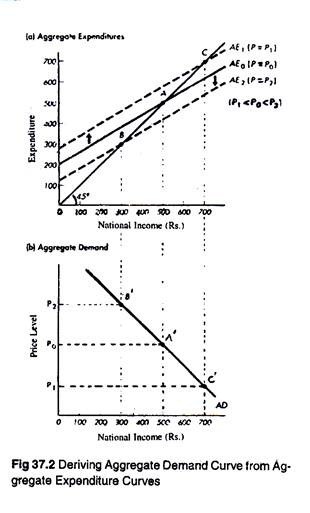

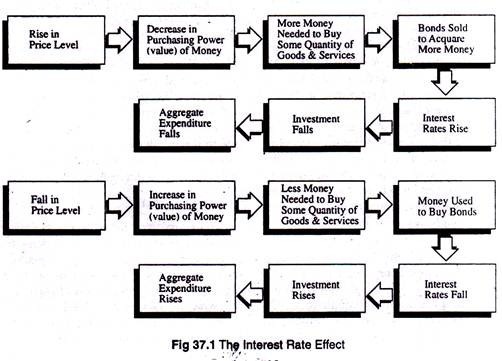

When the general price level rises, (i.e., when there is inflation in the economy), the value of money, i.e., the purchasing power of each rupee falls. This simply means that more money is now required to buy a fixed basket of goods and services. This point is illustrated in Fig. 37.1.

The converse is also true. When the general price level is halved, the household requires half the money to be able to buy the same fixed quantity of good because the purchasing power of each rupee has doubled.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When prices rise, people need money more to be able to buy the same amount of goods and services. How do people get this extra money? By selling other assets like bonds, or stocks and shares. This means that excess demand of money is equivalent to excess supply of bonds.

This excess of bonds depresses bond prices. And this implies a rise in the market rate of interest. The rise in the rate of interest is necessary to encourage people to buy more bonds. But a rise in the interest rate will have an undesirable consequence: it will lead to a fall in investment expenditure.

When the general price level tends to fall, people will require less money (or real balance) to be able to purchase the same quantity of goods and services.

The money saved in the process will now appear to be surplus. This money is no longer required to buy goods and services. It will be held in the form of liquid balance. What will people do with this surplus money? In fact, excess supply of money implies excess demand for bonds.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, people will use their money holdings to buy bonds and other income-earning assets. The excess demand for bonds increases bond prices. This is equivalent to a fall in the rate of interest. This, in its turn, will encourage increased investment expenditures, pushing aggregate expenditures up.

Fig. 37.1 shows the interest rate effect, the relationship among three crucial macro-variables, viz., the general price level, interest rates, and aggregate expenditure. When the price level rises, interest rates also rise, but aggregate expenditure falls. The converse is also true—when the price level falls, interest rates also fall and aggregate expenditure is pushed up.

3. The International Trade Effect:

Net export, like consumption, investment, and government spending is an important component of aggregate expenditure in an open economy. In our discussion of national income accounting we have noted that net export is a function of domestic income. Net export is also likely to be affected by the domestic price level.

If prices of domestically produced goods rise while prices of foreign goods as also the foreign exchange rate remain constant, domestic goods become more expensive relative to foreign goods.

When the price of domestic goods increases in relation to prices of foreign goods, export falls and import rises. This means that net export falls. The end result will be a fall in aggregate expenditure. The converse is also true.

This is known as the international trade effect of a change in the domestic price level. This causes aggregate expenditure to change in the opposite direction. This means that a rise in the domestic price level will cause net expenditure on foreign goods to fall.

4. The Sum of the Price Level Effect:

A lower price level increases autonomous consumption (the wealth effect), autonomous investment (the interest rate effect) and autonomous net exports (the international trade effect). When the price level falls, aggregate expenditure rises.

This is reflected in the upward shift of the aggregate expenditure line from AE0 to AE1 in Fig. 37.2. A higher price level generates an exactly opposite effect. In this case the aggregate expenditure schedule shifts downward from AE0 to AE1. The expression within bracket shows the price level corresponding to each level of aggregate expenditure.