Here is a compilation of term papers on ‘Consumer Surplus’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on ‘Consumer Surplus’ especially written for commerce students.

Term Paper on Consumer Surplus

Term Paper Contents:

- Term Paper on the Meaning of Consumer Surplus

- Term Paper on Marshall’s Measure of Consumer Surplus

- Term Paper on the Measurement of Consumer Surplus as an Area under the Demand Curve

- Term Paper on Consumer Surplus and Gain from a Change in Price

- Term Paper on the Measurement of Consumer’s Surplus through Indifference Curve Analysis

- Term Paper on the Critical Evaluation of the Concept of Consumer’s Surplus

Term Paper # 1. Meaning of Consumer Surplus:

The concept of consumer surplus was first formulated by Dupuit in 1844 to measure social benefits of public goods such as canals, bridges, national highways. Marshall further refined and popularised this in his ‘Principles of Economics’ published in 1890. The concept of consumer surplus became the basis of old welfare economics. Marshall’s concept of consumer’s surplus was based on the cardinal measurability and interpersonal comparisons of utility.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to him, every increase in the consumer’s surplus is an indicator of the increase in social welfare. Consumer’s surplus is simply the difference between the price that ‘one is willing to pay’ and ‘the price one actually pays’ for a particular product.

Concept of consumer’s surplus is a very important concept in economic theory, especially in theory of demand and welfare economics. This concept is important not only in economic theory but also in economic policies such as taxation by the Government and price policy pursued by the monopolistic seller of a product. The essence of the concept of consumer’s surplus is that a consumer derives extra satisfaction from the purchases he daily makes over the price he actually pays for them.

In other words, people generally get more utility from the consumption of goods than the price they actually pay for them. It has been found that people are prepared to pay more price for the goods than they actually pay for them. This extra satisfaction which the consumers obtain from buying a good has been called consumer surplus.

Thus, Marshall defines the consumer’s surplus in the following words:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“Excess of the price which a consumer would be willing to pay rather than go without a thing over that which he actually does pay, is the economic measure of this surplus satisfaction….it may be called consumer’s surplus.”

The amount of money which a person is willing to pay for a good indicates the amount of utility he derives from that good; the greater the amount of money he is willing to pay, the greater the utility he will obtain from it. Therefore, the marginal utility of a unit of a good determines the price a consumer will be prepared to pay for that unit.

The total utility which a person will get from a good will be given by the sum of marginal utilities (SMI) of the units of a good purchased and the total price which he actually pays is equal to the price per unit of the good multiplied by the number of units it purchased.

Thus,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Consumer’s surplus = what a consumer is willing to pay minus what he actually pays.

= Σ Marginal utility – (Price × Number of units of a commodity purchased)

The concept of consumer surplus is derived from the law of diminishing margin utility. As we purchase more units of a good, its marginal utility goes on diminishing. It is because of the diminishing marginal utility that consumer’s willingness to pay for additional units of a commodity declines as he has more units of the commodity. The consumer is in equilibrium when marginal utility from a commodity becomes equal to its given price.

In the other words, consumer purchases the number of units of a commodity at which marginal utility is equal to price. This means that at the margin what a consumer will be willing to pay (i.e., marginal utility) is equal to the price he actually pays. But for the previous units which he purchases, his willingness to pay (or the marginal utility he derives from the commodity) is greater than the price he actually pays for them. This is because the price of the commodity is given and constant for him and therefore price of all the units is the same.

Term Paper # 2. Marshall’s Measure of Consumer Surplus:

Consumer surplus measures extra utility or satisfaction which a consumer obtains from the consumption of a certain amount of commodity over and above the utility of its market value. Thus the total utility obtained from consuming water is immense while its market value is negligible. It is due to the occurrence of diminishing marginal utility that a consumer gets total utility from the consumption of a commodity greater than the utility of its market value.

Marshall tried to obtain the monetary measure of this surplus, that is, how many rupees this surplus of utility is worth to the consumer. It is the monetary value of this surplus that Marshall called consumer surplus.

To determine this monetary measure of consumer surplus we are required to measure two things. First the total utility in terms of money that a consumer expects to get from the consumption of a certain amount of a commodity. Second the total market value of the amount of commodity consumed by him. It is quite easy to measure the total market value as it is equal to market price of a commodity multiplied by its quantity purchased (i.e., P.Q.).

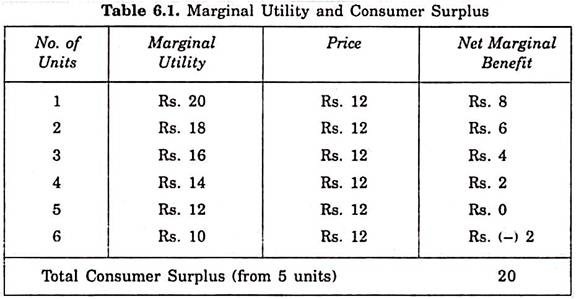

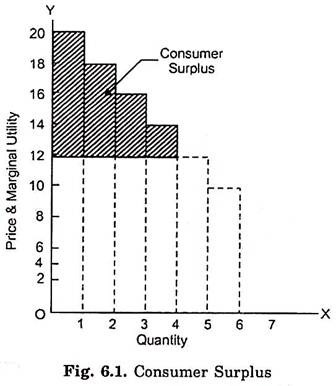

An important contribution of Marshall has been the way he devised to determine the monetary measure of the total utility a consumer obtained from the commodity. Consider Table 6.1 which has been graphically shown in Fig. 6.1.

Suppose the price of a commodity is Rs. 20 per unit. At price of Rs. 20, the consumer is willing to buy only one unit of the commodity. This implies that utility which the consumer gets from this first unit is at least worth Rs. 20 to him otherwise he would not have purchased it at this price. When the price falls to Rs. 18, he is prepared to buy the second unit also.

This again implies that the second unit of the commodity is at least worth Rs. 18 to him. Further, he is prepared to buy third unit at price Rs. 16 which means that it is at least worth Rs. 16 to him. Likewise, the fourth and fifth units of the commodity are at least worth Rs. 14 and Rs. 12 as he is prepared to pay these prices for the fourth and fifth units respectively, otherwise he would not have demanded them at these prices.

Now, we can interpret the demand prices of these units in a slightly different way. The prices that the consumer is prepared to pay for various units of the commodity means the marginal utility which he gets from these units of the commodity demanded by him. This marginal utility of a unit of a commodity for an individual shows how much he will be willing to pay for it.

However, actually he has not to pay the sum of money equal to the marginal utility or marginal valuation he places on them. For all the units of the commodity he has to pay the current market price. Suppose the current market price of the commodity is Rs. 12. It will be seen from the Table 6.1 and Fig. 6.1 that the consumer will buy 5 units of the commodity at the price because his marginal utility of the fifth unit just equals the market price of Rs. 12.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This shows that his marginal utility of the first four units is greater than the market price which he actually pays for them. He will therefore obtain surplus or, net marginal benefit of Rs. 8 (Rs. 20 – 12) from the first unit, Rs. 6 ( Rs. 18 – 12) from the second unit, Rs. 4 on the third unit and Rs. 2 from the fourth unit and zero on the fifth unit. He thus obtains total consumer surplus or total net benefit equal to Rs. 20.

Term Paper # 3. Measurement of Consumer Surplus as an Area Under the Demand Curve:

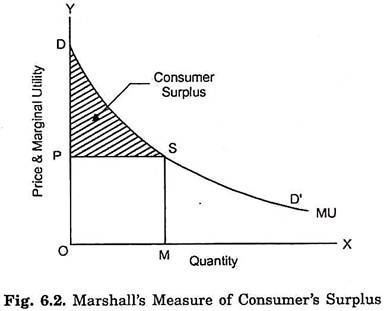

The analysis of consumer surplus is based on discrete units of the commodity. If we assume that the commodity is perfectly divisible, which is usually made in economic theory, the consumer surplus can be represented by an area under the demand curve.

The measurement of consumer surplus from a commodity is illustrated in Fig. 6.2 in which along the X-axis the amount of the commodity has been measured and on the Y-axis the marginal utility (or willingness to pay for the commodity) and the price of the commodity are measured. DD’ is the demand or marginal utility curve which is sloping downward, indicating that as the consumer buys more units of the commodity, his willingness to pay for the additional units of the commodity or in other words marginal utility which he gets from the commodity falls.

Marginal utility shows the price which a person will be willing to pay for the different units rather than go without them. If OP is the price that prevails in the market, then the consumer will be in equilibrium when he buys OM units of the commodity, since at OM units, marginal utility is equal to the given price OP.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Mth unit of the commodity does not yield any consumer’s surplus to the consumer since this is the last unit purchased and for this price paid is equal to the marginal utility which indicates the price he is prepared to pay rather than go without it. But for the intra-marginal units i.e., units before Mth unit, marginal utility is greater than the price and, therefore, these units yield consumer’s surplus to the consumer. The total utility of a certain quantity of a commodity to a consumer can be known by summing up the marginal utilities of the various units purchased.

In Fig. 6.2, the total utility derived by the consumer from OM units of the commodity will be equal to the area under the demand or marginal utility curve up to point M. That is, the total utility of OM units in Fig. 6.2 is equal to ODSM. In other words, for OM units of the good the consumer will be prepared to pay the sum equal to Rs. ODSM. But given the price OP, the consumer will actually pay for OM units of the good the sum equal to Rs. OPSM.

It is thus clear that the consumer derives extra utility equal to ODSM minus OPSM = DPS, which has been shaded in Fig. 6.2. To conclude when we draw a demand curve, the monetary measure of consumer surplus can be obtained by the area under the demand curve over and above the rectangular area representing the total market value (i.e., P.Q. or the area OPSM) of the amount of the commodity purchased.

If the market price of the commodity rises above OP, the consumer will buy fewer units of the commodity than OM. As a result, consumer’s surplus obtained by him from his purchase will decline. On the other hand, if the price falls below OP, the consumer will be in equilibrium when he is purchasing more units of the commodity than OM. As a result of this, the consumer’s surplus will increase. Thus given the marginal utility curve of the consumer, the higher the price, the smaller the consumer’s surplus and the lower the price, the greater the consumer’s surplus.

It is worth noting here that in our analysis of consumer’s surplus, we have assumed that perfect competition prevails in the market so that the consumer faces a given price, whatever the amount of the commodity he purchases. But if the seller of a commodity discriminates the prices and charges different prices for the different units of the good, some units at a higher price and some at a lower price, then in this case consumer’s surplus will be smaller.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, when the seller makes price discrimination and sells different units of a good at different prices, the consumer will obtain smaller amount of consumer’s surplus than under perfect competition. If the seller indulges in perfect price discrimination, that is, if he charges price for each unit of the commodity equal to what any consumer will be prepared to pay for it, then in that case no consumer’s surplus will accrue to the consumer.

Term Paper # 4. Consumer Surplus and Gain from a Change in Price:

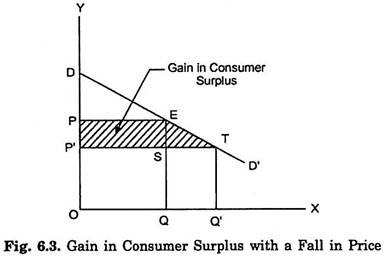

In our above analysis consumer’s surplus has been explained by considering the surplus of utility or its money value which a consumer obtains from a given quantity of the commodity rather than nothing at all. However, viewing consumer surplus derived by the consumer from the consumption of a commodity by considering it in all or none situation has rather limited uses. In a more useful way, consumer’s surplus can be considered as net benefit or extra utility which a consumer obtains from the changes in price of a good or in the levels of its consumption.

Consider Fig. 6.3 where DD shows the demand curve for food. At a market price OP of the food, the consumer buys OQ quantity of the food. The total market value which he pays for OQ food equals to the area OPEQ, that is, price OP multiplied by quantity OQ. The total benefit, utility or use-value of OQ quantity of food is the area ODEQ. Thus, consumer’s surplus obtained by the consumer would be equal to the area PED.

Now, if the price of food falls to OP, the consumer will buy OQ’ quantity of food and the consumer surplus will increase to P’TD. The net increase in the consumer’s surplus as a result of fall in price is the shaded area PETP’, (P’TD – PED = PETP’). This measures the net benefit or extra utility obtained by the consumer from the fall in price of food. This net benefit can be decomposed into two parts. First, the increase in consumer surplus arising on consuming previous OQ quantity of food due to fall in price.

Second, the increase in consumer surplus equal to the small triangle EST arising due to the increase in consumption of the food following the lowering of its price (PETP’ = PESP’ + EST’).

Term Paper # 5. Measurement of Consumer’s Surplus through Indifference Curve Analysis:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We have explained above the Marshallian method of measuring consumer’s surplus. Marshallian method has been criticised by the advocates of ordinary utility analysis.

Two basic assumptions made by Marshall in his measurement of consumer’s surplus are:

(1) Utility can be quantitatively or cardinally measured, and

(2) When a person spends more money on a commodity, the marginal utility of money does not change or when the price of a commodity falls and as a result consumer becomes better off and his real income increases, the marginal utility of money remains constant.

Economists like Hicks and Allen have expressed the view that utility is a subjective and psychic entity and, therefore, it cannot be cardinally measured. They further point out that marginal utility of money does not remain constant with the rise and fall in real income of the consumer following the changes in price of a commodity.

The implication of Marshallian assumption of constant marginal utility of money is that he neglects the income effect of the price change. But in some cases income effect of the price change is very significant and cannot be ignored. Marshall defended his assumption of constancy of marginal utility of money on the ground that an individual spends a negligible part of his income on an individual commodity and, therefore, a change in its price does not make any significant change in the marginal utility of money. But this heed not be so in case of all commodities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Prof. J.R. Hicks rehabilitated the concept of consumer’s surplus by measuring it with indifference curve technique of his ordinal utility analysis. Indifference curve technique does not make the assumption of cardinal measurability of utility, nor does it assume that marginal utility of money remains constant.

However, without these invalid assumptions, Hicks was able to measure the consumer’s surplus with his indifference curve technique. The concept of consumer’s surplus was criticised mainly on the ground that it was difficult to measure it in cardinal utility terms. Therefore, Hicksian measurement of consumer’s surplus in terms of ordinal utility went a long way in establishing the validity of the concept of consumer’s surplus.

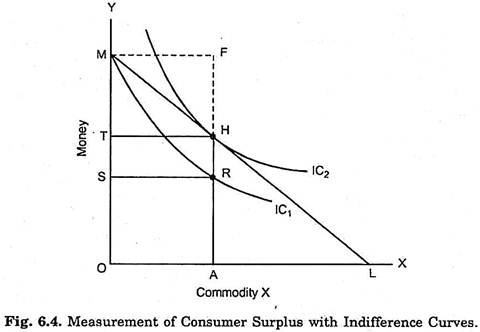

How consumer’s surplus is measured with the aid of Hicksian indifference curve technique is illustrated in Fig. 6.4. In Fig. 6.4, we have measured the quantity of commodity X along the X-axis, and money along the Y-axis. It is worth noting that money represents other goods except the commodity X. We have also shown some indifference curves between the given commodity X and money for the consumer, the scale of his preference being given.

Note that the assumption of constant marginal utility of money requires that indifference curves are vertically parallel to each other. We know that consumer’s scale of preferences depends on his tastes and is quite independent of his income and market prices of the good. This will help us in understanding the concept of consumer’s surplus with the aid of indifference curves.

Suppose, a consumer has OM amount of money which he can spend on the commodity X and the remaining amount on other goods. The indifference curve IC, touches the point M indicating thereby that all combinations of money and commodity X represented on IC, give the same satisfaction to the consumer as OM amount of money. For example, take combination R on an indifference curve IC1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It follows that OA amount of commodity X and OS amount of money will give the same satisfaction to the consumer as OM amount of money because both M and R combinations lie on the same indifference curve IC1. In other words, it means that the consumer is willing to pay MS amount of money for OA amount of the commodity X. It is thus clear that, given the scale of preferences of the consumer, he derives the same satisfaction from OA amount of the commodity X as from MS amount of money. In other words, he is prepared to give up MS (or FR) for OA amount of commodity X.

Now, suppose that the price of commodity X in the market is such that we get the budget line ML (price of X is equal to OM/OL). We know from our analysis of consumer’s equilibrium that consumer would be in equilibrium where the given budget line is tangent to an indifference curve.

It will be seen from Fig. 6.4 that the budget line ML is tangent to the indifference curve IC2 at point H, where the consumer is having OA amount of commodity X and OT amount of money. Thus, given the market price of the commodity X, the consumer has actually spent MT amount of money for acquiring OA amount of commodity X. But, he was prepared to forgo MS (or FR) amount of money for having OA amount of X. Therefore, the consumer pays TS or HR less amount of money than he is prepared to pay for OA amount of the commodity X rather than go without it.

Thus, TS or HR is the amount of consumer’s surplus which the consumer derives from purchasing OA amount of the commodity. In this way, Hicks explained consumer’s surplus with his indifference curves technique without assuming cardinal measurability of utility and without assuming constancy of the marginal utility of money.

Since Marshall made these dubious assumptions for measuring consumer surplus, his method of measurement is regarded as invalid and Hicksian method of measurement with the technique of indifference curves is regarded as superior to the Marshallian method.

Term Paper # 6. Critical Evaluation of the Concept of Consumer’s Surplus:

The concept of consumer’s surplus has been severely criticised ever since Marshall propounded and developed it in his Principles of Economics. Critics have described it as quite imaginary, unreal and useless. Most of the criticism of the concept has been levelled against the Marshallian method of measuring it as an area under the demand curve.

However, some critics have challenged the validity of the concept itself. Marshallian concept of consumer’s surplus has also been criticised on the ground of its being based upon unrealistic and questionable assumptions.

We shall explain below the various criticisms levelled against this concept and will critically appraise them:

1. It has been pointed out by several economists that the concept of consumer’s surplus is quite hypothetical, imaginary and illusory. They say that a consumer cannot afford to pay for a commodity more than his income. The maximum amount which a person can pay for a commodity or for a number of commodities is limited by the amount of his money income. And, as is well-known, a consumer has a number of wants on which he has to spend his money.

Total sum of money actually spent by him on the goods cannot be greater than his total money income. Thus what a person can be prepared to pay for a number of goods he purchases cannot be greater than the amount of his money income. Viewed in this light, there can be no question of consumer getting any consumer’s surplus for his total purchases of the goods.

But, in our view, the above criticism misses the real point involved in the concept of consumer’s surplus. The essence of the concept of consumer’s surplus is that consumer gets excess psychic satisfaction from his purchases of the goods. It is true that with his limited money income, consumer cannot pay more for his total purchases than that he actually pays. But nothing prevents him from feeling and thinking that he derives more satisfaction from the goods than the price he pays for them and if he had the means he would have been prepared to pay much more for the goods than he actually pays for them.

2. Another criticism against consumer’s surplus is that it is based upon the invalid assumption that different units of the goods give different amount of satisfaction to the consumer. We have explained above how Marshall calculated consumer’s surplus derived by the consumer from a good.

Consumer purchases the amount of a good at which marginal utility is equal to its price. It is assumed that marginal utility of a good diminishes as the consumer has more units of it. This means that while at the margin of the purchase, marginal utility of the good is equal to its price, for the previous intra-marginal units, marginal utility is higher than the price and, on these intra-marginal units, consumer obtains consumer’s surplus.

Now, the critics point out that when a consumer takes more units of a commodity it is not only the utility of the marginal unit that declines but also all previous units of the commodity he has taken. Thus, as all units of a commodity are assumed alike, all would have the same utility. And when, at the margin, price is equal to the marginal utility of the last unit purchased, the price will also be equal to the utility of the previous units and consumer would, therefore, not get any consumer’s surplus.

But this criticism is also not acceptable, because even though all units of a commodity may be alike, they do not give same satisfaction to the consumer; as consumer takes the first unit, he derives more satisfaction from it and when he takes up the second unit, it does not give him as much satisfaction as the first one, because while taking the second unit, a part of his want has already been satisfied.

Similarly, when he takes the third unit, it will not give him as much satisfaction as the previous two units, because now a part of his want has been satisfied. Similarly, when he takes the third unit, it will not give him as much satisfaction as the previous two units. If we accept the above criticism, we then deny the law of diminishing marginal utility.

But diminishing marginal utility from a good describes the fundamental human tendency and has also been confirmed by observation of actual consumer’s behaviour. The concept of consumer’s surplus is derived from the law of diminishing marginal utility. If law of diminishing marginal utility is valid, the validity of the Marshallian concept of consumer’s surplus cannot be challenged.

3. The concept of consumer’s surplus has also been criticised on the ground that it ignores the interdependence between the goods, that is, the relations of substitute and complementary goods. Thus, it is pointed out that if only tea were available and no other substitute drinks such as milk, coffee, etc., were there, and then the consumer would have been prepared to pay much more price for tea than that in the presence of substitute drinks.

Thus, the magnitude of consumer’s surplus derived from a commodity depends upon the availability of substitutes. This is because if only tea were available, consumer will have no choice and would be afraid that if he does not get tea, he cannot satisfy his given want from any other commodity.

Therefore, he will be willing to pay more for a cup of tea rather than go without it. But if substitutes of tea are available, he would not be prepared to pay as much price since he will think that if he is deprived of tea, he will take other substitute drinks like milk and coffee. Thus, it is said that consumer’s surplus is not a definite, precise and unambiguous concept; it depends upon the availability of substitutes.

The degree of substitutability between different goods is different for different consumers, and this makes the concept of consumer’s surplus a little vague and ambiguous. Marshall was aware of this difficulty and, to overcome this, he suggested that, for the purpose of measuring consumer’s surplus, substitute products like tea and coffee is clubbed together and considered as one single commodity.

4. Prof. Nicholson described the concept of consumer’s surplus as hypothetical and imaginary. He writes, “Of what avail is it to say that the utility of an income of (say) £ 100 a year is worth (say) £ 1000 a year”. According to Prof. Nicholson and other critics, it is difficult to say how much price a consumer would be willing to pay for a good rather than go without it.

This is because consumer does not face this question in the market when he buys goods; he has to pay and accept the price that prevails in the market. It is very difficult for him to say how much he would be prepared to pay rather than go without it. However, in our view, this criticism only indicates that it is difficult to measure consumer’s surplus precisely. That a consumer gets extra psychic satisfaction from a good than the price he pays for it is undeniable.

Moreover, as J.R. Hicks has pointed out “the best way of looking at consumer’s surplus is to regard it as a means of expressing it in terms of money income gain which accrues to the consumer as a result of a fall in price.” When the price of a commodity falls, the money income of the consumer being given, the price line will switch to the right and the consumer will be in equilibrium at a higher indifference curve and as a result his satisfaction will increase.

Thus, consumer derives more satisfaction at the lower price than that at the higher original price of the good. This implies that fall in the price of a commodity, and, therefore, the availability of the commodity at a cheaper price adds to the satisfaction of the consumer and this is in fact the change in consumer’s surplus brought about by change in the price of the good.

Prof. J.R. Hicks has further extended the concept of consumer’s surplus considering it from the viewpoint of gain which a consumer gets from a fall in price of a good. Moreover, the concept of consumer’s surplus is useful and meaningful and not unreal because it indicates that he gets certain extra satisfaction and advantages from the use of amenities available in civilised towns and cities.

5. The concept of consumer’s surplus has also been criticised on the ground that it is based upon questionable assumptions of cardinal measurability of utility and constancy of the marginal utility of money. Critics point out that utility is a psychic entity and cannot be measured in quantitative cardinal terms.

In view of this, they point out that consumer’s surplus cannot be measured by the area under the demand curve, as Marshall did it. This is because Marshallian demand curve is based on the marginal utility curve in drawing which it is assumed that utility is cardinally measurable.

Further, by assuming constant marginal utility of money, Marshall ignored income effect of the price change. Of course, income effect of the price change in case of most of the commodities is negligible and can be validly ignored. But in case of some important commodities such as food-grains, income effect of the price change is quite significant and cannot be validly ignored.

Therefore, the Marshallian method of measurement of consumer surplus as area under the demand curve, ignoring the income effect, is not perfectly correct. However, this does not invalidate the concept of consumer’s surplus. J.R. Hicks has been able to provide a money measure of consumer’s surplus with his indifference curve technique of ordinal utility analysis which does not assume cardinal measurement of utility and constant marginal utility of money. Hicks has not only rehabilitated the concept of consumer’s surplus but also extended and developed it further.

Despite some of the shortcomings of the concept of consumer surplus, some of which are based on wrong interpretation of the concept of consumer surplus, it is of great significance not only in economic theory but also in the formulation of economic policies by the Government. The concept of consumer’s surplus has a great practical importance in the formulation of economic policies by the Government.