In this article we will discuss about the law of variable proportions.

In the short run we study the behaviour of output as more and more units of a variable factor (labour) are applied to a given quantity of a fixed factor. So, output becomes a function of labour input alone. If this is SO the short-run production function may be expressed as: Q = f (L), where Q is output and L is labour input.

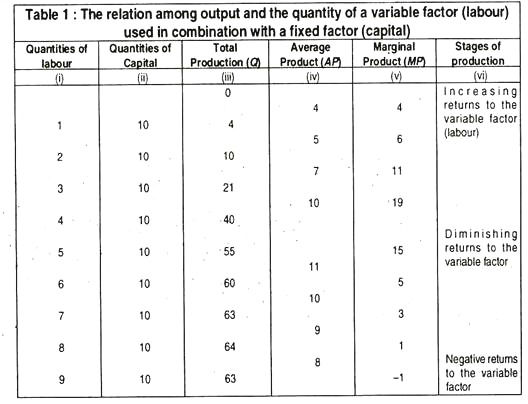

Table 1 illustrates the relationship between input changes and output changes in the short run. Three concepts bear relevance in this context viz., total product (TP), average product (AP), and marginal product (MP). Here Q is total product. It refers to the total amount produced by all the factors employed in a fixed time period. AP is output per unit of input.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is calculated by dividing TP by the amount of the variable factor, e.g., labour (L). So, AP = TP/L = Q/L. This is output per unit of labour or per worker. The marginal product is defined as the change in total product associated with a small change in the usage of the variable factor. It may be expressed as MP = ∆Q/∆L where ‘∆’ denotes any change. Thus, MP is the ratio of the change in Q and change in L.

The data presented in Table 1 are shown graphically in Fig 1 In Table 1 we show the total product that results from employing 1 to 9 units of labour [Column (i)] in combination with a fixed quantity (10 units) of capital [Column (ii)]. Column (iv) shows the corresponding AP figures. Each figure of column (iv) is arrived at by dividing each element of Column (iii) by the corresponding element of Column (i). Column (v) gives the MP figures.

Each element in this column shows the contribution (addition) made to the total product (TP) by the one additional unit of labour. In other words MP is the change in total product which results from a change in the usage of the variable factor (i.e., labour) by one unit. For example, when one unit of labour is employed, TP is 4. When two units are employed, TP is 10 Therefore, the contribution of the second unit is 10 – 4 = 6 units. This is the MP of labour.

The Law of Variable Proportions:

If we look at Table 1 carefully we can identify three stages of the production process in the short run:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) In the first stage, when additional units of labour are employed, TP increases more than proportionately and MP also increases. This is the stage of increasing return to the variable factor (labour)

(2) In the second stage TP increases, no doubt, but not proportionately In other words, the rate of increase of TP falls. This means that MP diminishes This is the stage of diminishing return to the variable factor (labour) This is perhaps the most important stage of the production process in the short run.

(3) In the third stage, TP itself diminishes and the MP is negative. This is the stage of negative return to the variable factor (labour).

The three stages together constitute the Law of Variable Proportions. Since the second stage is the most important one from the practical point of view, we often ignore the other two stages in most discussions. This is why the Law of Variable Proportions is also known as the Law of Diminishing Returns, which is universally applicable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The law simply states that “when increasing quantities of a variable factor are used in combination with a fixed factor, the marginal and average product of the variable factor will eventually decrease.” In our example, AP increases until 5 men are employed. It declines thereafter. But, MP declines earlier. It rises until 4 men are employed and declines when 5 and more men are employed.

No doubt, the data presented in Table 1 are hypothetical. But, the relationship shown among TP, MP and AP is widely applicable. From Table 1 we may also discover the relationship between MP and AP.

Three points may be noted in this context:

1. So long as MP exceeds AP, the AP must be rising.

2. Thus, it follows as a corollary that only when MP falls below the level of AP, AP falls.

3. Since MP rises when MP is exceeding AP, while AP falls where MP is less than AP, it follows that where AP is at a maximum, it is equal to MP. This is why the MP curve intersects the AP curve at the latter’s maximum point. (This relation between the margin and the average is mathematical).

In this context, we may note that MP can be zero or negative, but AP can never be so. AP may be very small but is always positive as long as TP is positive. However, such a situation does not carry any significance. In our example, where 9 men are employed, TP falls. So, no profit-maximising producer would consider employing so many workers.

The Basis of the ‘Law’:

Why does the law hold? The answer to this question is that the application of varying quantities of one factor to a fixed quantity of another changes the proportions in which the two factors are combined. In practice, it is observed that some factor combinations are more efficient than others.

As the producer moves towards the best combination, MP and AP both tend to rise. As, in subsequent stages of the production process, he moves beyond it, MP and AP both fall (because diminishing returns set in). The basic point is that the best combination of factors is the one which gives the optimum scope for division of labour and specialisation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the short run it is not possible to install a new machine or increase the size of an agricultural farm. So, more men are usually employed in conjunction with a fixed amount of capital or land. Thus, if in the short run it is not possible to increase the usage of all factors, there will be a change in the factor proportion.

Suppose, 10 workers can cultivate a plot of land in the best possible way. If more men are employed the opportunities for specialisation will gradually diminish (because each may get into other way) and diminishing returns set in. The Law of Diminishing Returns is also known as the Lazy of Non-proportional Returns.

The law may be stated as follows: If, in the short run, it is not possible to change the usage of all factors or change them strictly in proportion, output will follow the Law of Non-Proportional Returns (because every extra unit of variable factor will gradually make less and less contribution to the total product).

The proximate reason for diminishing returns is the presence of a fixed factor which is used with variable factors. Thus, the Law operates in agriculture due to fixity of land as a factor. If too many workers are employed on land, TP will fall. It is so because there were too many workers that go into each other’s way.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, the law would not operate if the farmer brought more land under the plough, along with more hired workers. In this case, however, we would no longer be considering the application of varying quantities of one factor together with a fixed factor (land). Thus, if both the factors, viz., land and labour were varied the law would not operate. Thus, in short, the Law of Diminishing Returns refers only to the effect of varying factor proportions.

Consequences of the ‘Law’:

If the law did not operate, i.e., if MP were constant, it would be simply possible to increase food production of a country by employing more and more workers on a fixed plot of land. In that case there would be no food problem due to population growth. It would be possible to feed the entire world by employing more and more workers on the fixed amount of land in the world.

However, this does not happen in reality. Instead, a rise in the proportion of labour to land would be found, eventually, to lead to diminishing returns — a continuous decline in marginal product as more and more workers are employed on a fixed plot of land. The land area of the earth is fixed. So, the only way to avert the operation of the Law of Diminishing Returns is to introduce technological progress in agriculture.

An example of this is Green Revolution which has succeeded in most developing countries of Asia. There is no denying the fact that in the absence of rapid technological progress in agriculture, population growth will ultimately lead to a steady decline in the living standards of the people in most parts of the world.

Application of the Law:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In our illustration above, we have concentrated on labour as the variable factor. But, the law is equally applicable to other factors such as labour, capital and entrepreneurship. As more and more capital is applied to a fixed supply of land and labour both the marginal product and the average product of capital will, at some point, start falling. The same thing will happen to the productivity of land as more and more land is combined with a fixed amount of labour and capital.

The Validity of the Assumptions:

However, it may be noted that the Law of Diminishing Returns applies when other things remain the same. This means that the law is based on two implicit assumptions. The first assumption is that the efficiency of the other factors remain unchanged. The second assumption is that there is no improvement in the techniques of production.

But in reality we observe that the efficiency of other factors does not remain constant. Moreover, improvements in technical knowledge or the art of cultivation often tend to offset the effects of the Law of Diminishing Returns. It may be noted that any improvement in the methods of production is likely to increase the productivity of the factors of production and shift both the AP and the MP curves upwards. But, this does not mean that the Law does not hold.

As Stanlake has rightly commented, “It is still true that in the short period (when other things can change very little) increments in the variable factors will at some point yield increments in output which are less than proportionate. In some less developed regions where there is little or no technical change and population is increasing, we can, unfortunately, see the Law of Diminishing Returns operating only too clearly”.

Importance of the Law:

The Law of Variable Proportions carries economic significance. In fact, cost of production and productivity of factors are closely interrelated. More specifically, cost and productivity are the reciprocal of each other. If MP increases, a business firm’s marginal cost of production will fall. Similarly, if AP increases, average variable cost will fall.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The converse is also true. This is why the Law of Diminishing Returns is also known as the Law of Increasing Marginal Cost. In fact, a firm’s short-run marginal and average cost curves are U-shaped due to the operation of the Law of Diminishing Returns.