Read this article to learn about Industrial Policy and Competition Policy:- 1. Competition Policy 2. Industrial Policy 3. Research and Development (R&D) 4. Strategic International Competition Policy 5. Sunrise and Sunset Industries 6. Economic Geography 7. Social Cost of Monopoly 8. Price Discrimination Monopoly 9. Distribution of Monopoly Profits and other things.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 1. Competition Policy:

Competition policy enhances efficiency by promoting or safeguarding competition.

Competition policy entails rules about conduct of firms or the structure of industries.

The former aims to prevent abuse of a monopoly and the later seeks to prevent monopolies arising. Some industries are natural monopolies. Economies of scale are so large that breaking them up makes no sense, and competition from other firms provides no discipline. They are natural monopolies and have been nationalized in many European countries to use them for the interest of the society.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After 1980s, the UK government pioneered the privatisation of those industries. Other countries have followed suit. Since scale economies do not vanish with privatisation, continuous regulation has been necessary. First, we deal with cases where scale economies are less significant. Competition policy has become an important form of government intervention.

Other motives for intervention are to increase production efficiency. If inefficiency arises not from scale economies and market power, from the environmental externalities, what other market failure can we think about? Essentially all the other externalities are associated with production.

Industrial policy aims to offset externalities affecting production decisions by firms. We discuss four such production externalities or market failures privacy of intervention and knowledge creation; spill-overs across borders that lead to policy competition between governments; capital market failures that explain why new businesses are so difficult to start; and locational externalities.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 2. Industrial Policy:

Inventions and the patent system — Information is a very special economic commodity. It is very hard to trade information the buyers need to see it but, having seen it has no incentive to pay for it. One example is invention. The problem is that the inventor finds it difficult to privately appropriate the benefits since imitators cannot be excluded.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The solution to this market failure is a patent system. A temporary provision for the inventors who can appropriate profit from investment during this period. A patent is a temporary legal monopoly awarded to an inventor who registers the invention.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 3. Research and Development (R&D):

Research is the process of invention. Development makes research commercially viable.

Most countries subsidies R&D, which account for about 2% of GDP in advance countries. What are the market failures in R & D that patent system cannot offset?

This is because the large projects are risky for individual company. For example, Boeing describes a project as betting the company failure of one new project could threat its existence as a company. Private individuals and business executives are normally more risk-averse.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Private firms may undertake less R&D than socially desirable because the social return exceeds the private return to those making the decisions.

Society needs a lower rate of return, or use a lower discount rate to evaluate the future benefits of the project, for two reasons first, the government can pool the risk across many projects in its portfolio; second, even if a project goes wrong, the government can spread burden thinly across the entire population.

Thus society needs a smaller risk premium than that required by private individual. This is one reason to subsidies R&D. Thus the private benefit to the investor becomes a social benefit. This is the second reason to subsidies R&D.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 4. Strategic International Competition Policy:

Consider the commercial airline industry again. Effectively there are two large firms left in the world market. Boeing and McDonnell-Douglas have merged in 1996 and became one company. The other major player is the European Consortium Airbus Industry.

Suppose Airbus asks the governments of its member producers (Germany, France, the UK and Spain) for launch aid, a grant or loan on favourable terms to help with R & D on new aircraft. In addition to the standard arguments for R & D support, what extra issues does international competition raise?

First, Airbus may survive and succeed even without government support. If so, public subsidies are simply a transfer payment to Airbus shareholders, a poor idea. Second, launch aid may be necessary for the success of the Airbus company. If Airbus pulls out, Boeing-McDonnell- Douglas will be the sole producer without fear of competition.

In that it would be surely easy for Boeing to raise the price of commercial aircraft. Consumers of air-travellers would be the loser because they will have to pay higher prices, and Boeing would be the sole beneficiary as they will earn monopoly profits. It may be worth preventing this.

Financial support is a commitment by European governments not to let Airbus to be bullied out of the industry. Boeing may conclude that there is no point attempting a price war to force Airbus to exit. A European commitment may prevent a price war that would otherwise occur. Strategic international competition can provide a rationale for strategic industrial policy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Industrial and Competition Policy # 5. Sunrise and Sunset Industries:

The next aspect of industrial policy concerns dynamic change, the rise and fall of industries and firms within them. Sunrise industries are the emerging new industries of the future. Sunset industries are those of the past, now in long-term decline. For example, sunrise industries are computer and genetic.

Sunset industries in developed economies of the West are old heavy industries, such as steel and shipbuilding, now suffering from huge excess capacity, undercut by more efficient producers in the Pacific basin.

Why not leave such changes to market forces? What market failures might justify government intervention through industrial policy? We begin with Sunrise industries. In these industries, two types of market failure are normally put forward to justify the-case for government intervention. First, there may be imperfection in the market for lending to new companies and new industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Banks and other traditional lenders may be too risk-averse, or too unfamiliar with the new business, to lend money needed through the early loss-making years. Second, the market may be too slow to provide the relevant training and skills catch 22 situation.

These arguments may justify industrial policy to subsidies Sunrise industries. But two questions need answering. First, why are markets short sighted and uninformed? Second, even if markets get it wrong, can the government do better? The strategy of trying to outguess the market by ‘picking winners’ is highly discredited.

Civil servants and politicians are unlikely beat analysts in industry and finance. If industrial policy is to be pursued, it is better to diagnose the cause of market failure and provide incentive that market decision makers than take into account when undertaking their professional analysis.

Sunset industries present different problems. It may be desirable to spend what could otherwise be dole money on temporarily subsidizing the lame ducks to ease the transition. Sometimes, a sharp shock is needed to signal the extent of adjustment eventually required and the government’s commitment to seeing the adjustment take place. Strategic considerations are important here too.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 6. Economic Geography:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economic geography popularized by Paul Krugman means that firm’s location affects its production costs. A beneficial locational externality occurs if a firm’s costs are reduced by locating near similar firms. A firm’s costs of production depend on its proximity to other firms because of three reasons: the interaction of scale economies and risk, transport and transaction costs, and technological spill-overs.

Suppose a worker invests in very special skills, such as designing racing cars. With only one firm in the local market, the worker is dependent on one employer. Having this specific skill is really risky. With a cluster of similar employers, risks of workers fall. They no longer require such a large ‘risk premium’ or ‘compensating differential’ in their wage.

Labour is cheaper for firms. Where did scale economies come into argument? Without them, each locality could have a thinly smattering of every firm. It is the presence of scale economies that forces firms into all or nothing choices between different locations.

A second reason is transport costs. Shops may cluster because of transport costs for consumers but large producers cluster because of features of production. Closeness to raw material is an obvious example. Discovering a coal seam or iron ore leads to a profusion of heavy industrial business in the locality.

Most significant of all is the spill-over in technology itself. Important example Silicon Valley in California, clusters of computer-based producers who find it advantageous to be in proximity. Although in competition with one another, they also feed off each other’s ideas just as the most competent Professors attend each other’s seminars.

The same hold good in businesses from software design to satellite technology. In such examples, we can see that one firm’s cost curve depends on how many other similar firms are situated nearby. This idea of a locational externality clarifies a concept that politicians have discussed for years but which previously economists have had trouble providing with a coherent interpretation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The industrial base of a country or region is a measure of the stock of existing producers available to provide such locational externalities. This emphasis on industrial base carries the presumption that the externalities are more significant for producers than for consumers, because of the specificity of investment required and minimum size that scale economies imposed.

In contrast, if the minimum efficient scale of specific investment is large, countries or regions may find there are two equilibria — one in which nobody enters and one in which many firms enter, each benefit from the presence of the other.

Yet achieving the second outcome efficiently requires coordination of the entry decision of different producers to internalise the externality facing each firm it neglects the benefits that its own entry creates for other firms.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 7. Social Cost of Monopoly:

Competitive equilibrium is efficient, in the absence of market failure. Each industry expands output to the point at which P – MC = SMB = SMC. Resource re-allocation cannot make everyone better off. When an industry is imperfectly competitive, each firm has some monopoly power.

Since demand curve slope downward, Price is > MR = MC. The excess price over MC is a firm’s monopoly power. The price and SMB of the last unit of output then exceed the PMC and SMC of producing that last unit.

From society’s point of view, industry output is too small. Expanding output adds more to social benefit than to social cost. How do we measure the social cost of monopoly power and inefficient resource allocation?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Imperfect competition needs some scale economies to limit the number of firms an industry can support. None the less, to introduce the idea of the social cost of monopoly power it is convenient to ignore the economies of scale altogether.

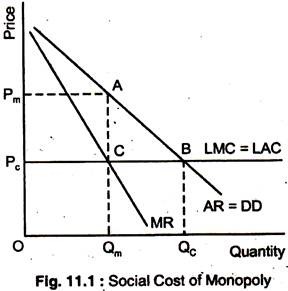

What happens if a competitive industry is taken over by a single firm that then operates as a multi-plant monopolist? In Fig. 11.1, under perfect competition LMC = SC. With constant return to scale, LMC = LAC of the industry. Given the demand curve DD, competitive equilibrium is at B.

The competitive industry produces an output QC at a price Pc. Now the industry has become monopolist, producing output QM at a price Pm where MC = MR. The area PMPCCA = monopoly profits from selling QM output at a price > MC = AC. The area ABC is the social cost of monopoly power.

At QM the SMB of another unit of output is PM but the SMC = PC. Society would try to raise output up to point 3 at which SMB = SMC. The area ABC is the social gain of extending output.

The industry has horizontal LMC = LAC. A Perfectly competitive industry produce at B, but a monopoly sets MC = MR to produce QM at price PM. Thus the monopoly profit is PMPCCA, but is a social cost or deadweight loss = ACB. Between QM and QC SMB > SMC and society will gain by expanding output by QC. ABC is the social gain by expansion.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The demand curve measures the MB to consumers of each unit of output and the MCC measures the extra resources used to make each unit of output. Hence the area between DD and IMC up to that output measures the total surplus to be divided between consumers and producers. Producers’ surplus (or profit) is the excess of revenue over TC. TC are the area under the LMCC up to this output.

Consumers’ surplus is the excess of consumer benefits over spending. It is the area under the demand curve at this output minus the spending.

In Fig. 11. 1, at the output QM is PMPCCA and consumer surplus is DAPM. This output is inefficient because it does not maximise the sum of producers’ and consumers’ surpluses. That is maximised at QC at which the area between the demand curve and the LMC is maximised.

The social cost of monopoly is the failure to maximise social surplus. This is found by adding together the deadweight burden such as the area ABC for all industries in which MC and MR are less than P and SMB. At an output below the efficient level, the deadweight burden area shows the loss of social surplus.

Is the social cost of monopoly really large? Some economists, such as Stigler believe it is small. Other economists, such as Professor F. M. Scherer, argued that it is as large as 7% of US GDP.

Why such disagreement? First, the area of the deadweight burden in Fig. 11.1 depends on the elasticity of demand curve. In calculating the deadweight burden under monopoly, different economists use different estimates of the demand elasticity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Second, the welfare cost of monopoly is not just the deadweight loss. Since monopoly may yield high profits to the firm, firms spend a lot to secure and acquire monopoly positions. We have also seen that existing oligopolists have an incentive to advertise too much in order to raise the fixed cost of being in the industry, an entry barrier to new firms.

Similarly, firms may devote large quantities of resources trying to influence the government in ways that enhance or preserve the monopoly power. They may also deliberately maintain extra production capacity to create a credible threat to flood the market if an entrance come in. Society may have to devote a large quantity of resources to lobbying the government or maintaining overcapacity are really waste.

Modern economic analysis also stressed the role of information. Those running a monopoly have inside information about the firm’s true cost opportunities. They know more than shareholders or a regulator. Perhaps the monopolist could have lower costs if its managers put in extra efforts.

Economists call this ‘managerial slack’ or X-inefficiency. Lack of competition gives the firm an ‘information monopoly’ on its own cost possibilities. Outsiders cannot find out. If a competitive firm gets lazy, it loses market share and goes out of market. If a monopolist gets lazy, it simply makes a bit of less profit. From the social point of view, its costs curve are unnecessarily high and spend extra resources to make this output.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 8. Price Discrimination Monopoly:

The social cost of monopoly arises because the monopolist cannot always price discriminate. Perfect price discrimination makes the demand curve and the MR curve coincide. Then P = MR = MC. The monopolist produces the socially efficient output.

Price discrimination is possible only in special circumstances. Consumers must not be able to set-up a second-hand market; and producer is unable to establish separate sub-markets. Price discrimination in services is easier since resale is impossible. For example, doctor operating a patient who cannot resale it to anybody else.

Price discrimination by large monopolists is precluded when an universal service requirement legally forcing the monopolist to supply to all part of the country at a uniform price, even though the price of rural delivery are much higher.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 9. Distribution of Monopoly Profits:

Society does not care just about the inefficiency of imperfect competition. It may also care about two other aspects of monopoly power the political power that large companies exert, and the distributional issue of the fairness of the large profit’s a monopolist can earn. Monopoly profits are a private tax.

The ultimate recipients of monopoly profits are the monopolist’s shareholders. Much of to stock market is held by the pension funds and insurance companies that eventually make payments to workers. Some monopoly profits go to the less well-off. But most do not.

Suppose the government imposes a profit tax how does this affect the monopolists output decision? It does not. For a given tax rate, higher pre-tax profits must raise post-tax profits. Hence the monopolist produces exactly the same output as in the absence of a profit tax and, facing the same demand curve, and will charge the same price as before.

A monopolist cannot shift the tax on to anybody else. Society can tax as much of the monopolist’s profits as it wants, without affecting the monopolist’s behaviour, at least in the short-run. An occasional windfall tax may remove monopoly profits without adversely affecting the incentive on efficiency.

However, the expectation of regular resort to such taxes will undermine incentives to invest. Cost would then become higher than they might have been.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 10. Must Liberalization Help:

We know that more competition is always better. Beginning from a distorted position, elimination of all market failures would always increase efficiency. But partial elimination or reduction can make things worse rather than better sometimes two distortions may offset each other. Removing just one makes the other worse.

Suppose there are large economies of scale and a falling ACC. A monopolist is bad for the reason outlined above, but it does at least produce on a large scale and let society benefit from scale economies. Suppose the government insists on more competition, say entry of a second firm.

Dividing the market would make both firms unable to reap scale economies. More competition may reduce profit and drive price close to MC; it may also reduce information monopolies, forcing more expenditure on cost reduction to shift cost curve down.

But if the scale economies are big enough, both producers have large costs than the original monopolist. Society may be worse off because it would have to spend more resources on production. With this brief discussion of market power, we can understand the role of competition policy.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 11. Competition Policy and the Society:

Society would definitely gain more from greater competition, if only it could be secured, then it would not lose from giving up economies of large scale by allowing fresh entry. Promotion of competition in certain industries is likely to be beneficial. This can be achieved by setting rules for conduct or by taking steps to ensure a market structure in which competition can prevail.

In the USA, competition policy has been based on breaking up big companies to achieve a market structure favourable to competition. UK competition policy, on the other hand, more pragmatic, a case-by-case assessment without a prior presumption that the existence of the monopoly power is bad.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 12. UK Competition Law:

Monopoly policy has been reassessed in the 1973 Fair Trading Act and amended in the Competition Act of 1980 and 1998. The 1973 Act introduced a Director-General of Fair Trading to supervise many aspects of competition and consumer law, including regulation of quantity and standards.

The Director-General is responsible for monitoring company behaviour and, subject to a ministerial veto, can refer individual cases to the competition commission for a thorough investigation.

A company can be referred to if it supplies more than 25% of the total market. The commission can also be given cases where two more distinct firms by implicit collusion operate to restrict competition. The commission investigates whether a monopoly, or potential monopoly, acts against the public interest.

There is no presumption that monopoly is bad. The commission is charged to investigate whether or not monopoly acts against the interest of the public, a wide brief that in recent years has stressed ‘maintenance and promotion of effective competition’.

The Restrictive Practices Court examines agreements between UK firms, such as collusive pricing behaviour. All agreements must be notified to the Director General of Fair Trading, who refers them to the court unless they are voluntarily abandoned or judged of trivial significance.

The court will find against these agreements unless they satisfy one of eight ‘gateways’ or justifications, for example, their removal would cause serious unemployment in the area.

For restrictive practices, the burden of proof lies on companies to show that they are acting in public interest. In contrast, the legislation of monopolies is more open-minded. The commission has to show companies are acting against the public interest.

The UK is also subject to the monopoly legislation of the European Union. Article 85 of the Treaty of Rome is similar to UK legislation on restrictive practices. Agreements have to be notified and are likely to be outlawed. Article 86 bans the abuse of a ‘dominant position’ as a monopolist.

The 1998 competition Act brought UK policy more inline with European Law. The term of reference of the competition commission were supplemented by two new prohibitions. Essentially, there is a ban on agreements that prevent, restrict or distort competition in the UK, and a ban on conduct that amounts to abuse of a dominant position within the UK.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 13. UK Competition Policy in Practice:

The competition commission has wide power to make recommendations, and the minister normally act on its recommendations. Yet only a few companies have so far been penalized as a result of investigations. More frequently, the commission has relied on informal assurances that criticised behaviour will be suspended.

It has investigated a wide range of cases, from beer to breakfast cereals, from contraception to cross-channel ferries. Since it has looked at each case with an open mind, its judgements have stressed different aspects of behaviour in different cases. A large market share has not always attracted an un-favourable judgement. For example, the ice-cream wars by Birds Eye Walls was a case in point.

The commission ruled that there was no evidence that BEW had refused to supply other wholesalers. It concluded that BEW had restricted and distorted competition, found no offsetting benefits to the public interest, and recommended that BEW be required to supply wholesalers on the same terms as to others.

It also has the power to investigate regulated industries such as utilities. In 1999 it reported on claims that charges by Vodafone, BT, etc. for calls from fixed phones to mobile phones were too high.

It concluded that emerging competition in telecommunication was not yet sufficient to discipline these monopoly suppliers, and that at the end of 1998 charges made by Cellnet and Vodafone were 22% higher than the public interest benchmark — calculated from a hypothetical suppliers, with the scale economies corresponding to a 25% above a public interest benchmark.

Therefore, the commission recommended that the licences of Cellnet, Vodafone and BT be modified to impose price ceilings on the charges.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 14. Restrictive Trade Practices (RP):

Since restricted practices legislation was first introduced in 1956, over 5,000 agreements have been registered. Most were abandoned before they went to the court. The result looks impressive as most explicit price-fixing has gone.

First, they may simply have forced collusive agreement underground. Recent legislation and policy has tightened up ‘information agreements’ that could be the basis of secret collusion. Second, the various ‘gateways’ have let some doubtful agreements be ratified.

Finally, tighter control of restrictive practices agreements between firms has been an incentive for merger. By formally merging, companies can continue old practices within the merged company.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 15. Mergers:

Merger means two firms can unite in two different ways to form one company.

A firm makes a takeover bid for another firm by offering to buy out the shareholders of the second firm. Managers of the victim firm will try to resist since they are likely to lose jobs, but the shareholders may accept the offer if it is attractive.

A merger is the voluntary union of two firms that they think they will do better together.

Are mergers in the public interest, or do they just create private monopoly?

The production process has several stages. The first stage might be iron ore extraction, the second stage is to manufacture steel from ore, and the third stage is the production of cars from steel.

A horizontal merger is the union of two firms at the same production stage in the same industry. A vertical merger is the union of two firms at different production stages in the same industry. In a conglomerate merger, the production activities of the two unrelated firms are joined together.

A horizontal merger may allow more economies of scale. One big car company may be better than two small ones if each firm was previously producing below minimum efficient scale. In vertical merger there may be gains in coordination and planning.

It may be easier to make long-term decisions about the best size and type of steel mill if a simultaneous decision is taken on the level of car production to which steel output forms an important input. The conglomerate mergers have very little opportunity for a direct reduction of production costs.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 16. Benefits of Mergers:

First, if the company has an inspired management team, it may be more productive to allow this team to manage both businesses. Second, by pooling their financial resources, the merged firms may enjoy access to cheaper borrowing, letting them take more risks and undertake larger research projects.

There may also be economies of scale in marketing. These gains could explain why merger make sense even for companies producing completely different product.

If companies achieve any of these benefits, they will be in a position to increase productivity and lower costs. These private gains are also social gains. If these were the only considerations, private and social calculations would coincide. However, in some situations private and social assessment may diverge.

First, the merger of two big firms gives the merged company a monopoly power from a large market share, which would enable them to restrict output and increase prices, a bigger deadweight loss for the society as a whole. Second, the merged company can also use its financial power. This danger is especially apparent in conglomerate mergers.

A tobacco producer and a food manufacturer can easily use their joint financial power to start price war in one of these industries. With large financial resources, they are not the first to go burst. By forcing out existing competitors, or holding their threat over potential entrants, they can easily increase their market share, deter entry, and charge higher prices.

Merger policy must thus compare the social gain with social costs.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 17. Mergers in Practice in the UK:

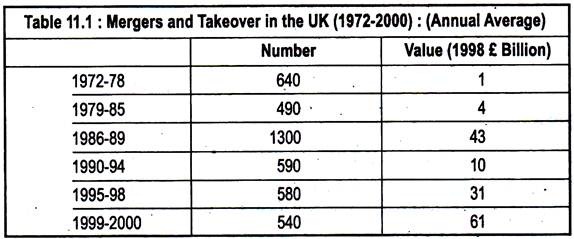

Table 11.1 shows annual average of takeovers and mergers involving only UK firms. It shows merger booms in the late 1980s and again after 1995. What was the reasons? The two merger booms coincided with high values of the stock market, which raised the value of both firms involved in the merger. Table 11.1 also shows the key aspect of the merger booms was the value of the mergers, more than the number of them.

Second, mergers are often associated with opportunities to rationalise industrial structure.

Two major developments in European markets were the periods preceding the creation of the single European market in 1992 and the launch of the euro (single currency) in 1999. A large market raises scope for scale economies and increase competition.

Third, the combination of new technology and deregulation has been changing market structure both in the UK and in its main trading partners. Segmentation of national markets has been breaking down in many industries including telecommunication, financial services and so on. Cross-border mergers have allowed leading players to respond to larger markets.

The increase in market size in the last 15 years has also influenced the type of mergers taking place. Conglomerate mergers had grown steadily in the 1960s and 1970s, and also in 1980s. However, financial deregulation has made it easier to raise finance.

Industrial and Competition Policy # 18. Merger Policy:

There had been no anti-merger policy to reduce the development of large companies.

There are currently two reasons for referring a proposed merger to an investigation by the competition commission:

(1) That the merger will promote a new monopoly as defined by 25% market share used in deciding references for existing monopoly positions, or

(2) That the merger involves the transfer of at least £70 million worth of company assets.

Since the merger legislation was introduced in 1965, only 4% of all merger proposals have been referred to the competition commission. For much of the period government policy has been to consent to, or actively encourage mergers.

Merger Policy in the UK reflected two assumptions:

(1) The cost savings from economies of scale and more intensive use of scarce management talent could be quite large; and

(2) The UK was part of an increasingly competitive world market so that the monopoly power of the merged firms, and the corresponding social cost of the deadweight burden, would be quite small. Large as they were, the merged firms were small in relation to European or world markets, and would face relatively elastic demand curves, giving little scope to raised price above MC.

Never the less, nearly half of the proposed mergers actually referred to the competition commission were found to be against the public interest. However, investigation was a lengthy process, a delay during which company share prices could change, upsetting the original negotiations about the terms on which the relative shares of the companies should be valued.

In practice, even the threat that a merger might be referred was often sufficient for the companies to abandon the merger.