Here is an essay on ‘Human Development’ for class 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Human Development’ especially written for school and college students.

Human development is an area in which much international attention has been directed. Human development includes many concepts; initially four such concepts were seen as ‘essential components’ of human development programme (HDP) (UNDP 1995).

These were:

(i) Productivity,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Equity,

(iii) Sustainability,

(iv) Empowerment.

Later the concepts of:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(v) Cooperation and

(vi) Security were also included in the HDP.

Productivity implies the enhancement of people’s capacity to produce and their full, better and enabled participation in the process of income generation and remunerative employment. Equity is providing accessible equal opportunities by effectively eliminating all barriers to economic and political participation; sustainability ensures that all forms of capital—physical, human and environmental—should be replenished. Empowerment means that development for the people is brought about by the people, i.e., participatory development.

Cooperation demonstrates the concerns with people as individuals and their interaction within the community. The idea of co-operation also includes the idea of ‘social capital’; security encompasses freedom from threats, repression, hurtful disruption in daily life, unemployment, food security, and also economic security.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The concept of human development is defined as enhancement of people’s capabilities, choices and contributions. The term ‘enhancement’ implies that human development is a dynamic, evolutionary and continuous process. By ‘contribution’ we mean the necessary participatory harmonic relation between the individual and the community—be it local, national—or humanity at large.

Human development is also largely dependent on the freedom to make choices—be it economic, political, associational, residential or habitual in nature, freedom from hunger, fear, unemployment, exclusion, discrimination and persecution. The term ‘capability’ comprises all aspects of human, physical, intellectual and social endowments.

It includes a variety of needs which need to be fulfilled in order to enhance a person’s capacities and abilities such as good health, nutritious food, functional (purposive) education, convenient housing, clean environment, safe neighbourhood, etc.

HDP addresses the functional relations between its three components — capabilities, choices, and contribution. Enhancement should take place on all three planes simultaneously; the first two capabilities and choices are centred largely around the individual, whereas ‘contribution’ is the bond between the individual and the society.

Each of these three components of the HDP has both intrinsic and instrumental values. Between them the three accommodate the most—if not all—important concepts of human development. Capabilities and choices would very well suggest empowerment, productivity, security and equity, and contribution indicates cooperation, participation and sustainability.

The ‘capability approach’ introduced by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen describes welfare in terms of capability to function. It states that whether a person or community is poor or non- poor depends on his capability to function in the community.

The HDP is also based on ideas of co-operation and participation of individuals in community life, and the freedom to make choices. Sen explains that the nature of development can be assessed by the degree of freedom of choice that people enjoy in a community.

Amartya Sen states in his theory of entitlements that poverty is not just a matter of being poor but of lacking certain minimum capabilities. Sen has also maintained that the deficiency of traditional economics is that it concentrates on the national product, aggregate income and total supply of goods, rather than the entitlements of the people and the capabilities that these generate.

Entitlement refers to the set of alternative commodities that a person can command in a society using all the rights and obligations that he faces. For example, an illiterate person might feel happy if he possesses a book, but the book is of little use to him. The concept of human well-being in general and poverty in particular revolves around not the availability of commodities, but ‘functioning’, that is, what a person does with the commodities he possesses.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Sen identifies five sources of disparity between real incomes and actual advantages:

(i) Personal heterogametic, such as those connected with disability, illness, age or gender.

(ii) Environmental diversities e.g. impact of pollution.

(iii) Variations in social climate and social capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Differences in relational perspectives.

(v) Distribution within the family.

Sen makes it clear that the feeling of goodness does not change the objective reality of deprivation. Thus we see that Sen’s capability approach is an inaugural part of the HDP, and it goes a long way in explaining why growth without development is harmful for societies.

The UNDP defines human development as ‘a process of enlarging people’s choices’. This depends not only on income but also on other social indicators such as life expectancy, education and health provision. The UNDP introduced Human Development Index (HDI) in 1990 in its first annual Human Development Report.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The HDI does not depend solely upon per capita GNP as an indicator of human development. It combines a measure of PCI with life expectancy and literacy rate. The HDI is not the first index that has tried to put various socioeconomic indicators. A forerunner is Morris’ ‘Physical Quality of life Index’ which came in 1979.

It was a composite of three indicators of development:

(i) Infant mortality,

(ii) Literacy, and

(iii) Life expectancy conditional on reaching the age of one.

A country’s performance in term, if income per capita might be significantly different from that measured in terms of these basic indicators. Some countries, comfortably placed in the ‘middle income’ bracket, nevertheless display literacy rates that barely exceed 50%, infant mortality rates close to 100 death per 1000 babies, and undernourishment among a significant proportion of the population. On the contrary, there are instances of countries with low and modestly growing incomes that have shown dramatic improvements in these basic indicators.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

HDI is the weighted average of three indicators of development:

(i) Life expectancy at birth, which also indirectly reflects infant and child mortality rates;

(ii) Educational attainment of the society, measured by a combination of adult literacy [(2/30) rd weight] and enrolment rates at primary, secondary and tertiary education [(1/3) rd weight]; and

(iii) Per capita income at real GDP per capita.

To construct the index, first a deprivation index is constructed for each of the three indicators. It is constructed by taking the difference between the maximum value of index, minus the actual value of the index, divided by the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the index

Life Expectancy:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The welfare of a nation is not dependent solely on the per capita income of the country, but the general well-being of the people of the country. Life expectancy at birth is an estimate, at the time of birth, of the average age a person will attain. The higher the life expectancy of a nation, higher is its degree of well-being.

Life expectancy is calculated according to the formula:

According to UNDP, the minimum and maximum values for life expectancy are 25 years and 85 years, respectively. Therefore the life expectancy for a country will be 0.833, when its actual life expectancy is 75 years: 75-25/85-25 = 0.833.

Educational Attainment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Educational attainment is a major indicator of the degree of progress made by a country.

It is comprise of two parts:

(i) Adult literacy rate; and

(ii) Enrolment rate for primary, secondary and tertiary education.

Hence, educational attainment

= 2/3(adult literacy index) + 1/3 (gross enrolment index)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Income Index:

Per capita income alone is not a perfect measure of development and has not one but many shortcomings, but in a combined measure (such as HDI) it has an important role to play. In the HDI, income serves as a surrogate for all dimensions of human development not reflected in a long and healthy life and in knowledge. Income is adjusted because achieving a respectable level of human development does not require unlimited income.

According to UNDP, the minimum and maximum possible per capita incomes are taken to be $100 and $40 000 at purchasing power parity (PPP), respectively. Per capita income at real GDP is adjusted’ after a certain upper limit ($5,000 in PPP, 1992) is crossed.

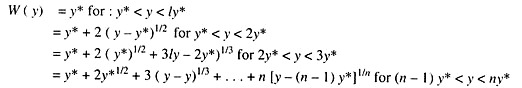

Less weight is given to higher incomes after this point on the grounds that there is diminishing marginal utility to higher incomes The world average income is taken as the threshold level (y*) and any income level above this level is discounted using Atkinson’s formulae for the utility of income

The main problem with this formula was that it discounted the income above the threshold level very heavily, penalizing countries in which income exceeds the threshold level. Hence, in many cases, income loses its relevance as a proxy for all dimensions of human development other than a long life and knowledge.

Thus attempts were made to rectify this problem, and a new method of calculation was adopted. By this method, Income Index is calculated by subtracting the natural log of 100 from the natural log of current income, and dividing it by (log 40,000 – log 100).

The advantages of this formula are that, firstly, it does not discount income as severely as the previous formula. Secondly, it discounts all income above a certain level. Lastly, the middle income countries are not penalised unduly. Moreover, as income rises in these countries, they continue to receive recognition for their increasing income as a potential means for further human development.

The final index then stands as

HDI = 1/3(income index) + 1/3 (education index) + 1/3 (life expectancy).

Using these three measures of development and processing data for 175 countries, the HDI ranks all three countries into three groups:

1. Low Human Development [0.000 – 0.499]

2. Medium Human Development [5.000 – 0.799]

3. High Human Development [0.800 – 1.000]

The creation of composites from such fundamentally different indicators—such as life expectancy and literacy—is like adding apples and oranges together. It is arguable that rather than create composites, we can view the different indicators and then judge the overall situation ourselves.

The advantage of a composite index is its simplicity—it is far easier and appears more ‘scientific’ to say that a country X has an index of 8 out of 10 than to laboriously detail that country’s achievements in five different spheres of development.

The HDI might look scientific but that is no reason to accept the implicit weighting scheme that it uses because it is just as ad hoc as any other. It cannot be otherwise. Nevertheless, the HDI is one way to combine important development indicators and for this reason it merits our attention. Why do you think that HDI needs to be modified to accommodate gender issues? We examine, in this context, the construction of gender related human development index.

The Human Development Index (HDI) measures the average achievement of a country in basic human capabilities. The HDI indicates whether people enjoy a long and healthy life, are educated and knowledgeable, and enjoy a decent standard of living.

HDI is the weighted average of three indicators of development, namely:

(1) Life expectancy at birth—which also indirectly reflects child and infant mortality rate,

(2) Educational attainment of the society—measured by a combination of adult literacy [(2/3)rd weight] and enrolment rates at primary, secondary and tertiary education [(1/3)rd weight], and

(3) Per capita income— at real GDP per capita.

However, the HDI does not take into account the inequality present between men and women in a society.

Attempts have been made to construct a gender disparity adjusted HDI. First, each of the three components of the HDI was expressed in terms of the female value as a percentage of the male value. Then the overall HDI was multiplied by this simple average female-male ratio to obtain the gender-disparity-adjusted HDI.

There were two problems with this exercise — first they did not relate the female to male ratio to the overall level of achievement in a society. It makes considerable difference whether gender equality exists at a lower or a higher level of achievement.

Secondly, each society can choose its level of ‘aversion to gender inequality’ (e), depending on where it starts and what goals it wants to achieve over what period of time. A country can let e to be zero (no policy preference for gender equality adopted) or infinity (only achievements of women get a positive weight and the relative achievements of men are ignored).

The Gender Development Index (GDI) consists of some indicators comprising the HDI, but it also takes note of the inequality in achievement between men and women. The methodology used imposes a penalty for inequality, such that the GDI falls when the level of achievement increases. The greater the gender disparity in basic capabilities the lower a country’s GDI is compared with its HDI.

The GDI is simply the HDI discounted for gender inequality. Another index to be considered is the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). The GEM examines whether women and men are able to participate actively in economic and political life and take part in decision-making. While the GDI focuses on expansion of capabilities, the GEM is concerned with the use of those capabilities to take advantage of the opportunities of life.

In order to construct the GDI, once data have been collected for gender disparities in life expectancy, adult literacy, combined enrolment and income, next, the explicit trade-off between greater gender equality and higher average achievement is calculated. For example, Mexico has an average combined enrolment ratio of 4-5% for females and 66% for males.

Iran’s average combined enrolment ratio is higher at 68%, but it shows greater gender inequality, with a female enrolment ratio of 61% and male ratio of 74%. The judgment of which is the better social outcome depends on the weight given to the objective of achieving equity. In the calculations, this is represented by an adjustable parameter e, which measures the ‘penalty’ for inequality.

The higher the ‘aversion to inequality’, the larger the value of e for the weighing procedure. If e = 0 (no aversion to inequality), then Iran’s performance is better than Mexico’s because its average enrolment ratio is higher. That is the principle used in calculating HDI.

But if the equity preference is sufficiently high, reflecting a strong social objective of achieving equality, then Mexico’s performance is better than Iran’s. The GDI calculations are usually based on e = 2, the harmonic mean of female and male achievements.

When calculating life expectancy, allowance is made for the biological edge that women enjoy in living longer than men. The calculation of life expectancy allows for this factor in its choice of fixed goal posts, by taking a range of 27.5 years to 87.5 years as the minimum and maximum values for female life expectancy and a range of 22.5 years to 82.5 years for male life expectancy.

In adjusting this component for gender differences in the new GDI calculations, women’s and men’s actual life expectations relative to their maximum values are separately calculated and then combined in an equity sensitive way. For educational attainment, the GDI gives 2/3rd weight to adult literacy and 1/3rd weight to combined primary, secondary and tertiary enrolment, as in the HDI.

GDI’s third component, income, raises more serious issues of estimation. In most countries there is substantial disparity between men and women in earned income, but data on such disparity are sorely lacking. GDI estimates that fail to include an estimate of gender disparities in earned income would be deficient. The shares of earned income would be deficient.

The shares of earned income for men and women are derived by calculating their wages as a ratio to the average national wage and multiplying this ratio by their shares of the labour force. Their shares of earned income are then divided by their population shares. If there is gender disparity between these two proportional shares of earned income, average real GDP per capita is adjusted downwards accordingly. The size of the downward adjustment depends on the value of ϵ.

The value of GDI is always lower than the value of the HDI, since gender inequality exists in every country. The four top-ranking countries in the GDI are Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark. These countries have adopted gender equality and women’s empowerment as a conscious national policy.

The bottom five places in ascending order are occupied by Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Several conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of GDI rankings first, no society treats its women as well as its men. As many as 45 countries have a GDI value below 0.5, showing that women suffer the double deprivation of gender disparity and low achievement.

Second, gender inequality does not depend on the income level of a society. China has ten GDI ranks above Saudi Arabia, though its real per capita income (PPP adjusted) is only a fifth of Saudi Arabia’s. Lastly, significant progress has been made since the 1980s in removing gender inequality, though much still needs to be done.

The Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) concentrates on participation — economic, political and professional. It differs from the GDI which is concerned primarily with the basic capabilities and living standards. Like the HDI and GDI, the GEM focuses on a few selected variables even though participation can take many forms.

It concentrates on three broad classes of variables:

1. For power over economic resources based on earned income, the variable is per capita income in PPP dollars (unadjusted).

2. For access to professional opportunities and participation in economic decision making, the variable is the share of jobs classified as professional, technical, administrative and managerial.

3. For access to political opportunities and participation in political decision making, the GDI and GEM treat the income variable differently. In the GEM, income is evaluated not for its contribution to basic human development, but as a source of economic power that frees the income earner to choose from a wider set of possibilities and exercise a broader range of options.

For access to professional opportunities and participation in economic decision making, the variable chosen is women’s share of jobs classified as administrative or managerial and professional or technical. In most developing countries, the proportion of women in administrative jobs and managerial posts is less than 10%.

The third variable is access to political opportunities and participation in political decision making. The variable chosen for the GEM is representation in the parliament, in both upper and lower houses. The average representation of women in parliament worldwide is 10%. The three dimensions are valued equally in constructing the GEM. In computing the index, the value of ԑ is 2, same as that of GDI.

The GEM examines outcomes in economic and political participation. These outcomes could be caused by structural barriers to women’s access to these arenas, or they could be the result of choices by both women and men on their desired roles in the society.

In most countries, industrial or developing, women are not yet allowed equality in terms of professional or political opportunities. Thus, much progress needs to be made in removing gender inequality in almost every country of the world.