The below mentioned article provides an overview on capital formation in a country.

Meaning:

Capital accumulation refers to the process of adding to the country’s stock of capital over time which permits roundabout methods of production and, hence, greater productivity.

This then enhances future income streams to society and consequently raises future consumption.

It is “the process of adding to our stock of machinery, tools, buildings, and so on, over time. If our stock of capital at the end of the year is larger than it was at the beginning, the difference represents the amount of capital we have accumulated during the year.” It also goes by the name investment. Annual net investment is the addition to society’s capital stock in an accounting year.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In a fundamental sense, capital formation is possible when a society produces a surplus of consumer goods sufficient to satisfy the wants of the workers engaged in producing capital, i.e., producing goods which are not themselves consumed during the period. That is to say, capital formation is the difference between production and consumption.

The problem of capital formation is concerned with how to get savings out of current production to form capital. Since production is a continuous process, same amount of capital always depreciates in the process of use, the worn out capital must be replaced if the existing stock of capital is to be maintained. So capital formation necessitates production of new capital goods in excess of the amount required to replace worn out capital. In brief, gross fixed capital formation includes depreciation while net capital formation excludes it.

In the words of Todaro: “Capital accumulation results when some proportions of present income are saved and invested in order to augment future outputs and incomes.” New factories, machinery, plant and equipment’s and materials increase the physical capital stock of a nation and these vast array of capital make it possible to expand the level of output of a country. These directly productive investments are supplemented by “investments in what is often known as social and economic infrastructure (roads, electricity, water and sanitation, communications, and the like) which facilitate and integrate economic activities.”

For example, investment by an Indian farmer in a new technology (tractor) may increase total output of wheat or rice which he can produce, but without adequate transport facilities to bring surplus product in local markets his investment may not add any value to actual food output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, capital in a country is formed by foregoing present consumption and diverting these resources to the production of future wealth. Thus, during the process of capital accumulation, one has to make a choice between present output and future output: the less a country produces for current consumption, the larger of its resources are utilised for capital formation. And, ultimately, capital formation triggers future consumption.

But LDCs are so poor that they stay at the subsistence level of consumption. It is absolutely impossible on the part of the poor people who form the majority to curtail consumption. Thus, while in developed industrial countries 20 p.c. to 30 p.c. of income are channelled into capital formation through the saving-investment process, many of the LDCs struggle hard to save and invest even 10-15 p.c. of their national income. The urgency of fulfilling immediate consumption competes for scarce resources, leaving little scope for capital formation.

In this connection, it may be noted that some countries like India have been experiencing capital accumulation to the tune of more than 30 p.c. of GDP. Thus, shortage of capital is not to be considered as an obstacle to development. In other words, development economists no longer subscribe to the logic of the vicious circle argument.

Underdevelopment is not to be attributed to poor capital formation. They argue that other factors like poor quality of institutions and governance are the prime causes of failure to develop many developing countries. Even then, the importance of capital accumulation is undeniable.

Importance of Capital Formation:

Capital accumulation plays a very important role in the process of economic development of a poor country. According to Nurkse, the vicious circle of poverty in poor LDCs can be broken through capital formation. The importance of capital formation for increasing production and productivity can be traced to the writings of early history of economic thought.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In rich countries the amount of capital per head is large while in poor countries it is small. Capital accumulation sets off rich from poor countries in the modem age and the industrial era in general from the past history of the world.

The importance of capital formation as a kingpin of economic development is clear from the following facts:

First, capital formation is required to provide a growing population with more necessary facilities of tools and machinery of production. All these tools and implements contribute directly to productive process. These facilities may take the form of tangible physical capital like factories, machinery, equipment’s in both industry and irrigation for agricultural production. It also takes the form of social overheads: investments in roads, transport and communication, health and education, etc. Economic development is impossible in the absence of these crucial elements.

Secondly, capital accumulation itself serves as an important vehicle of technical progress—the improvement in the art of production. The British industrial revolution was the product of improved technology. Technology provides the benefits of specialisation, shorter working hours, and the creation of skilled jobs, large scale production. Capital accumulation is similarly the handmaiden of technological progress. A. K. Cairn-cross adds: “Development as an on-going process rests on the constant injection of new technology and on the capacity to generate and absorb technical change.”

Thirdly, as the facilities per head of the working population rise, it increases human skills and capabilities which are examples of human capital. Both education and measures to improve health care are two important forms of human capital formation. Education improves the quality of labour as well as the quality of physical capital. The capacity to absorb physical capital is indeed limited by investment in human capital that improves the future growth performance of an economy.

Finally, a rapid rate of capital accumulation leads to an increase in the supply of tools and machinery per worker. Output per worker can be increased if we devote more time and labour to the production of more capital goods.

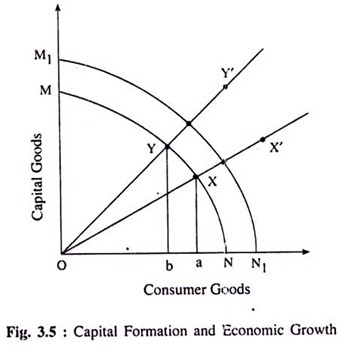

In Fig. 3.5 the possible effects of capital formation on economic growth have been explained. On the horizontal axis, consumer goods is measured while capital goods is measured on the vertical axis. MN is the production possibility boundary that an economy can produce various combinations of both the goods with the given inputs. Lines OXX’ and OYY’ represent growth paths. Obviously, OYY’ line describes a higher growth rate compared to OXX’ line. Suppose the country is initially producing at point X on the MN curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The rate of annual consumption of consumer goods is now assumed to be OA. If productive capacity of the economy grows at 2 p.c. p.a., the production possibility frontier then shifts outwards by the same percentage to M1N1. If the country decides to employ its resources to the production of capital goods by the same proportion its growth path will be represented by OXX’.

But for capital formation what is required is the sacrifice of current consumption. Let consumption decline by the amount ab. This means an increase in capital formation. This then shifts production point to Y. Faced with more capital goods the growth rate of the country increases. After a lapse of some years, the economy’s growth path will be represented by OYY’ line.

Thus, a lower volume of current consumption causes a rapid economic growth rate—the production possibility frontier would then shift to point Y’ indicating more production of both capital goods and consumption goods. This combination, however, is unobtainable for the economy on the path OXX’. It is thus obvious that capital accumulation plays an important role in promoting economic development.

However, an important question relating to the policy decision may be raised here. Is restriction on current consumption necessary or sufficient to promote economic development? The notion of trade-off between current consumption and future consumption is an important element that influences development policy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, capital accumulation has certain costs and benefits. By investing or adding to its existing capital stock, a society can outperform others by producing higher output in future years. But it involves a cost—the sacrifice of current consumption in order to have a higher future output or consumption. In the words of Richard T. Gill: “The process of capital accumulation therefore typically involves a choice between today’s consumption and tomorrow’s output, between today’s comfort and tomorrow’s economic growth.”

The Processes or the Stages of Capital Formation:

Capital accumulation involves the mobilisation of an economic surplus to increase the stock of future output and consumption. The question then arises: how is such capital to be created or increased, or in other words, how is capital formation accelerated? As capital formation is the result of savings, it, therefore, depends on savings out of current income. It is better to indicate the three essential stages or process of capital formation. How much capital will, in fact, be accumulated depends in the first instance on how much is saved.

These stages of capital formation are:

(i) Creation of savings,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Mobilisation of savings through a wide range of different sources, and

(iii) The act of investment itself, by which resources are used for increasing the capital stock.

(i) Creation of Savings:

Capital formation depends first on saving—both private and government. The volume of saving or propensity to save depends on: (i) will to save, and (ii) power to save.

The desire to save or the will to save depends on a variety of motives. People want to remain prepared for unforeseen emergencies. They want to make provision for education and health. Many people save because they want to improve their position and status in life. Savings take place through the financial intermediaries.

Anyway, the other motives behind the willingness to save are:

(i) Social and political conditions of the country,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Availability of financial infrastructures,

(iii) The level of literacy of people while making financial transactions through financial intermediaries,

(iv) The rate of interest on savings, etc.

However, the existence of the willingness to save is not sufficient to induce savings. There must also be the ability to save. Income is commonly regarded as the most important determinant of (private) saving. Governments also save out of receipts from taxation or from profit of nationalised enterprises. It also depends on the state of income distribution of a society— marginal propensity to save (MPS) is higher for the high income group while the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is higher for the low income group. A society composed of a large number of poor people has the less potentiality in raising the aggregate savings.

It may be noted here that the volume of investment is handicapped by saving. Thus, the shortage of capital cannot be solved merely by increasing the supply of finance. The two important internal sources of saving are voluntary and involuntary. The volume of saving depends on how much an individual is willing to forego consumption.

Such cut in consumption is not possible when the average income is low. In view of this, government may resort to forced saving through tax payments, inflationary policy, etc. But through taxes very little amount is collected when the community’s income is low. Ability to pay taxes depends on the volume of income. Inflationary financing has dangers too.

(ii) Mobilisation or Canalisation of Savings:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mere creation of savings is not enough. The second stage involves mobilisation of savings for investment purposes. It depends on the existence of a well-organised banking and other financial institutions and capital market as well to serve as a conduit between savers and investors. As savers and investors are two different persons in the community, institutions like banks, postal savings bank, insurance companies, etc. help to mobilise savings of them and pass them on to investors.

(iii) Conversion of Savings into Capital Assets:

The third and the final stage of capital formation consists of actual investment of monetary savings or conversion of monetary savings into capital goods. The volume of investment depends on a variety of factors, like the size of the market (both domestic and external) for the outlet of goods and machinery produced, machinery, entrepreneurial skill, availability of critical infrastructures of power, road and transport, and, most importantly, government policies.

The role of government in the realm of capital accumulation should not be underestimated. In an LDC, the responsibility of the government in this area can never be minimised. In these countries, the rate of capital accumulation is low because of low level of income. Private businesses also exhibit their apathy towards larger investment, particularly in .social overhead projects. In such situations, the government has to play a dominant role in increasing capital stock.

Sources of Capital Formation:

Now we will concentrate on the various sources from which necessary savings can be mobilised for the purposes of investment. The sources of capital formation are primarily two— internal and external sources. The internal or domestic sources are voluntary reduction in consumption by households and enterprises, and involuntary cut in consumption through taxation, compulsory lending to the government, or inflation, absorption of underemployed labour into productive work, profits of government enterprises, etc.

External sources of capital formation may come from the investment of foreign capital, restriction of consumption imports, or improvements in the country’s terms of trade or good commercial policy.

These sources of capital formation are:

Domestic Sources:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(A) Voluntary Savings:

It has been stated that saving is necessary to fund investment. Savings in an economy comes from three sources: the household sector, the business sector, and the government. The nature of savings consists of three types—voluntary, involuntary, and forced.

Voluntary savings are the savings that come through self-imposed reductions in current consumption out of disposable income of both the household and the business sectors. Since income is the most important determinant of saving (or consumption) the voluntary reductions in consumption may not fructify if the average income is very low.

It can, however, be reasonably expected that with the rise in income the marginal propensity to save will exceed the average propensity to save. Thus, in a poor country, voluntary household savings and business savings contribute little towards capital accumulation.

But, at the same time, it may be mentioned that inability to save consequent upon poor income is not a big constraint in developing countries. Voluntary reduction in consumption or an increase in saving may be made if efforts are made to attract more savings in a more productive way.

For instance, various saving promotion schemes may be introduced so that people can be persuaded to save against bad days. Further, people may be induced to divert their savings made in speculative and unproductive investments like gifts of jewellery to gods into more productive as well as non- speculative activities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, in many poor economies, household saving is not too insignificant as it has been assumed here. For instance, gross domestic saving as a percent of GDP in India in 2008-09 stood at 32.5 p.c. of which household saving alone contributed 22.6 p.c. of GDP.

A. W. Lewis and R. Nurkse postulated that disguised unemployment is an important source of saving in LDCs. An underdeveloped economy is often characterised as a labour-surplus economy. Labour surplus or disguised unemployment means the existence of large population in the agricultural sector whose marginal product falls to zero.

If these labour resources are transferred to the modem industrial sector, it then creates industrial surplus or profit that may be used for further growth and development. Lewis and Nurkse have suggested the use of unemployed or disguised unemployed workers in the industrial sector as well as various consumption projects like road-irrigation works. In this way, additional permanent capital is formed. To quote Nurkse: “The state of disguised unemployment implies, at least, to some extent a disguised saving potential as well.”

As things stand, the ‘unproductive’ surplus labourers on land are sustained or maintained by the ‘productive’ labourer engaged in the industrial sector or new capital projects. This then assumes that the transfer of labour from the rural sector is supported by productive members who do not increase their consumption.

The productive labourers are thus making ‘virtual’ saving; they produce more than they consume. The scheme is apparently attractive as no one is required to curtail his consumption, but capital accumulation takes place via reallocation of labour. If productive peasants left behind on agriculture were to send their ‘unproductive’ colleagues to work on capital projects and if they continued to feed them there, then their virtual saving would become effective saving.

Thus the use of disguised unemployment for the accumulation of capital could be financed from within the system itself .This method has the obvious advantage that it makes use, at small cost, of resources that would otherwise be idle. Anyway, the potential is there, but it is difficult to apply.

(B) Involuntary Savings—Taxation:

There is another method of financing development from domestic sources is the taxation. Fiscal policy and taxation play two major roles in the financing of development. First, it helps in maintaining an economy at full employment so that the saving capacity of the economy rises with the rise in per capita income. The second needs the designing of the tax policy in such a way that it raises the marginal propensity to save (MPS). It then appears that an appropriate taxation policy offers incentives to save and to work more.

The generation of additional saving through tax policy can take two main approaches—creation of tax incentives to encourage increased private saving and the use of tax instruments to reallocate investible resources to the public sector. If it is assumed that growth is impaired due to the lack of adequate incentives then the tax policy is to be designed in such a way that adequate concessions are granted so that incentives to work and save get boosted.

But, if resources are inadequate then the poor LDCs should make effort to raise resources required for investment through taxation. Saving brought about by taxation is called involuntary or forced saving. This then forces people to consume less. Thus, taxes provide the most appropriate instrument for increasing savings for capital formation.

However, the issue of raising revenue through taxation depends on a country’s taxation potential. Potential of taxes in generating revenue resources depends mainly on people’s income, the degree of inequality in the distribution of income, etc. For the most obvious reason, the actual ratio of tax revenue to national income’ is low in developing countries.

Imposition of taxes in these countries results in the reduction of disposable income of taxpayers that adversely affects ability to work and save. As progressive tax rates penalise economic success it depletes potential sources of saving. Above all, if political leadership in a country is given by the rich, imposition of high tax rates on them will be well high a difficult proposition. That is why agriculture in developing countries is under-taxed compared to the manufacturing and services sectors. In practice, land taxes contribute insignificant revenue.

But taxation as a method of development finance has its limits and difficulties. While involuntary savings may increase following a cut in consumption, voluntary savings may decline if people try to maintain their old consumption standards. This then reduces the volume of private savings. Moreover, all kind of taxes adversely affect the willingness and ability to work and save. Thus, while there is a great deal of necessity for raising revenues more by means of taxation, the obstacles to its effective realisation cannot be underestimated.

(C) Inflationary Finance:

If voluntary and involuntary savings are inadequate, inflationary finance then becomes the mechanism for capital accumulation. A government finances its expenditures by money creation as its revenue falls short of expenditure. When financing of expenditures by money creation is made their occurs an increase in aggregate spending. When idle productive capacity exists or if the country’s resources are underemployed, increased spending may stimulate aggregate output till the full employment is reached. This kind of inflationary finance mechanism works in two ways:

First, investment can generate its saving by raising the income level when the economy operates below the state of full employment. Secondly, this method allows redistribution of income from poor fixed income-earners having a low MPS to rich persons with a high MPS when the economy reaches the full employment stage. As a result, aggregate savings of the community become large which can be used for capital formation to accelerate the level of development.

Most importantly, as soon as the state of full capacity is reached, deficit financing causes inflation to flare up. Inflation is now considered as the means through which resources are redistributed between consumption and investment. Deficit financing thus imposes ‘forced’ savings as deficit-led inflation tends to reduce consumption propensities of the community whose level of income rises less than proportionately to the increases in prices. This forced saving can be utilised for the production of capital goods. This then triggers economic development.

But deficit financing is self-defeating in nature as it tends to generate inflationary forces in the economy. The trouble lies with the ‘dose’ of inflation—a ‘little’ or a ‘big’ one. It is said that a mild inflation has an encouraging effect on national output. A high rate or an erratic rate of inflation distorts all economic calculations. It may distort the pattern of capital formation. It may encourage the flight of capital to abroad (tax-free havens) where people perk their money to have an assured profitable return on invested money.

Further, in a situation of high rate of inflation, investment in plants and equipment’s by people becomes unattractive. On the contrary, investment tends to get channelized in diverse speculative activities. Thus funds collected through deficit financing ultimately become fewer than projected at the time of preparing deficit budget.

Finally, the consequences of inflation for international trade and balance of payments also impose heavy economic costs. Because of inflation, imports rise and exports fall. Thus, a country not only looses foreign market following a fall in export but also the ability to import industrial products and capital goods suffers badly.

In view of these problems, it is argued that this kind of financing is an ‘evil’, but a ‘necessary evil.’ However, in the end, we like to add that there is conclusive evidence that inflation speeds or hampers development: growth is positively related to inflation up to a certain rate of inflation and then negatively related.

To have a favourable impact of deficit financing on economic development, the magnitude of deficit financing and its phasing over the time horizon of development plan, it has to be kept within the ‘safe’ limits so that inflationary forces do not distort economic calculations. But it is difficult to set a ‘safe’ limit. Much of the success of deficit financing can be reaped if anti-inflationary policies are employed in a just and right manner.

External Sources:

Most of the developing countries have to supplement domestic savings as investment in these countries exceed saving capacity. It is the foreign borrowing that supplements domestic saving to bridge the savings- investment gap and the foreign-exchange gap. In filling the saving gap or domestic resource gap, foreign capital provides the necessary capital stock. But usually developing countries import more than what they export. To finance import, foreign-exchange gap needs to be bridged.

This can be done by drawing foreign exchange reserves. Since developing countries fail to build up large foreign exchange reserves because of excess of imports over exports, they then rely greatly on external financing—the capital assistance provided by government-to-government economic aid, the private investment of foreign capital, and the loans from the international agencies like the IMF, the World Bank, etc.

This ‘dual gap analysis’, on the one hand, shows that foreign assistance helps in promoting domestic savings, and, on the other, many of the (capital) goods required for growth is required to be imported with the help of foreign assistance. Such inflow of foreign capital thus adds additional capital but also allows domestic capital to be utilised in production.

In this way, it increases a country’s potential for greater investment required for higher growth. Foreign investments are usually made in capital-intensive projects. It then provides direct employment to many workers and stimulates the economy by raising incomes in the process. Further, multinational corporations or companies (MNCs) not only import capital but also act as the vehicle for the transfer of advanced technology to developing countries.

But the cost of external financing may often outstrip the benefits received by the recipient countries. It is argued by many that aid is unnecessary for development. It is inimical to development by fostering foreign dependence.

It weakens development effort and creates distorted consumption and production structures. Historical experience shows both successes and failures of foreign assistance in garnering resources for development. Finally, economic policy is considered as an important determinant of such external financing.

Economic policy does not operate in a vacuum; however, political issues often cloud the economic logic. For instance, India’s surplus generated in the pre-independent period was drained out through the channels of foreign aid and investment. National sovereignty often comes under threat from MNCs.

What emerges is that foreign aid is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for a country’s economic development. After 1980s, we heard about ‘aid fatigue’. Emphasis has now shifted from quantity to quality of such foreign development assistance.