The role of agriculture in economic development in India has been exhaustively studied from different viewpoints. It has often been approached from the point of view of the intersectoral transfer of resources, mainly agricultural surplus. Even more commonly, it has been viewed within the dualistic models, based on surplus labour but supplemented by a set of dynamic laws leading to the break-out point and to the disappearance of dualism.

For a long time, economists have debated on the relative importance of agriculture and industry in economic development of a country. Accordingly, different priorities have been assigned to these two key sectors of the economy in developmental planning. But the real issue is now whether agriculture should be accorded maximum priority in planning or, industrial development.

The truth is that agricultural development is possible without industry but the converse is not true, as industrial development is impossible without agriculture. History amply demonstrates that industrial revolution was preceded by agricultural revolution.

In 1953, Ragnar Nurkse first highlighted the importance of agriculture-industry interdependence in his balanced growth thesis. He argued that the two sectors of the economy should develop simultaneously by assisting one another on a reciprocal basis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

And any plan for industrialisation in particular and economic development in general must recognise this agriculture-industry interdependence.

Facts of Economic Life:

This point becomes very clear from the following facts of economic life:

1. Agriculture not only supplies food to a country’s growing population, it also supplies raw materials to a large number of industries. In truth, most of India’s traditional industries such as sugar, tea, jute, textiles, etc. are agro-based in nature. So a setback on the agricultural front adversely affects the growth of such industries. This is known as the supply linkage of agriculture with industry.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Agriculture has also demand linkage with industry. Agriculture creates demand for basic inputs such as chemical fertilizers, pesticides, etc., but also for capital goods, like tractors, pump sets, etc., and for light consumer goods such as two wheelers, radios, mobiles, TV sets etc., more so after the recent trend towards rural electrification.

With transformation of traditional agriculture, there is specialisation which leads to production for exports. If, at the same time, industry develops under the impact of agricultural growth, the two sectors become highly interdependent.

The industrial sector adds to demand for agricultural goods, and absorbs surplus labour which may raise yield per hectare. In turn, the agricultural sector provides a market for industrial goods out of rising real income, and makes a further contribution to development, through the release of resources—if productivity rises faster than the demand for commodities.

Thus, agricultural development is so much important for reducing urban unemployment and income inequality. Moreover, understanding the interactions between agriculture and the other sectors of the economy is crucial for shaping appropriate developmental policies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although agriculture is the dominant sector of the economy, it is characterised by low productivity and low supply elasticity. The low productivity per worker implies that the major proportion of the output is absorbed within agriculture itself, i.e., self-consumption is high. So, little surplus is left for use in industry and other sectors.

Thus, the larger the proportion of agricultural output absorbed by the industrial sector, the greater is the market for industrial goods. Agricultural growth—along with growth in exports and public investment—could lead to an external increase in demand for industrial goods.

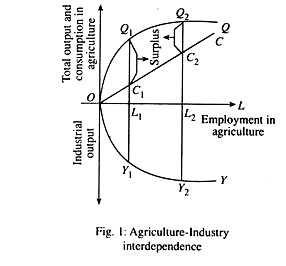

In Fig. 1, OL represents the level of employment in agricultural sector. At any level of employment, levels of total agricultural output and consumption within the agricultural sector are OQ and OC, respectively. When the level of employment is OL1, output is L1Q1, consumption is L1C1. So there is a surplus of C1Q1, for use outside agriculture. This surplus- can be utilised to maintain a level of employment in the industrial sector, which, in turn, results in an output level of L2Q2.

The slope of the curve OQ is positive but decreasing, implying the operation of the law of diminishing return in traditional agriculture. This arises due to fixity of land (as a factor of production) and other natural resources, yielding diminishing returns as there is an increase in the usage of other (complementary) inputs.

Technological progress, however, could avert the operation of the law, at least temporarily, by shifting the output (OQ) curve upward. In that case, for any given level of employment, output would be higher. This, in its turn, would result in large surplus, enabling a larger level of employment to be maintained in the industrial (and other) sectors.

The interactions between agriculture and non-agriculture change significantly over time in the process of economic development. In the early stages, agriculture is of crucial importance as the employer of 50% to 75% of the labour force and also as the source of more than half of the GDP. As development gains momentum, however, the relative importance of agriculture declines sharply while that of industry increases.

The secular decline in the relative importance of agriculture and the secular increase in the relative importance of industry can be explained by a number of factors:

1. Changes in the Pattern of Demand:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

First and foremost is the role of changes in the composition of demand. According to Engel’s law, the income elasticity of demand for food is generally less than one and it declines as income grows, while the income elasticity of demand for industrial product is considerably larger than one.

2. Input and Output Substitutions:

Secondly, various types of input and output substitution take place in the problem of development. Specifically, certain farm outputs are substituted by manufacturing outputs while others undergo increasing degrees of processing in the non-agricultural sectors. Industrial inputs, on the other hand, substitute for farm inputs to an increasing degree as income rises. For example, chemical fertilizers substitute for manure and capital goods for human labour and animal power.

3. Monetisation and Market Expansion:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, while the size of the market in a country expands as a result of population growth, rising PCI and monetisation, changes in factor cost tip the balance in favour of manufacturing.

4. Growth Stage Models and Dual Economy Models:

Attempts to systematize the discussion of the changing role of agriculture in the process of development have led to the formulation of a number of growth stage models and of dual economy models. These dual economy models treat the contribution of agriculture in terms of supply of surplus labour or provision of investable capital as if there strictly one-way transfers.

These models failed to appreciate the full extent of the complementarities between agriculture and industry. In order to comprehend better the interactions between the two sectors, we have to capture both the intersectoral transfer of surplus and the sectoral market contributions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The latter refers to the linkages that connect agriculture and industry by providing outlet for each other’s products and factors. In this essay, we analyse the roles of agriculture and industry in economic development through the interaction of the two sectors.

First, we discuss the investable agricultural surplus that may be transferred and utilised in the development of the industrial sector. This transfer can take place through the outflow of capital from agriculture, the outflow of labours agricultural taxation and the terms of trade. Next, we focus on the interdependence between agriculture and industry.

This approach emphasises the production function relationship and the output flows between the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. More specifically the development of agriculture may increase that sector’s demand for the intermediate inputs, such as insecticides, and machinery, provided by industry. It may also increase the supply of agricultural raw materials to the industrial sector.

These two aspects will be studied through the backward and the forward inter-industry linkage effect. The development of agriculture also provides employment for agricultural workers and, as their incomes rise, an increased demand for consumer goods produced in the industrial sector.

The availability of such goods often acts as an incentive to greater work effort, savings and productivity in the agricultural sector. These factors will be studied through the employment and income-generation linkage effect. This process of increasing interdependence of the sectors is called “sectoral articulation”.

Sectoral Capital Flows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to the Marxian thesis, the burden of providing surplus funds and surplus resources for the purpose of industrial capital formation in the early stages of development falls upon agriculture. Modern economists have challenged this orthodox view on the grounds that modern, chemical-biological agriculture requires heavy investments on irrigation, and water control. It,’ therefore, becomes necessary to stem or even reverse the resource outflow from agriculture if agricultural production is to keep up with the explosive population growth in many parts of the world.

Double Developmental Squeeze of Agriculture:

The logic of extracting the agricultural surplus can be described in terms of the double developmental squeeze of agriculture. This has two aspects, viz —the production squeeze, and the expenditure squeeze.

(i) The Production Squeeze:

The production squeeze can assume different forms. In the Marxist-Leninist approach, output can be extracted directly through compulsory delivery at low prices to the non-agricultural sector. Alternatively, it can be extracted through a combination of high farm prices and high farm taxes.

The production squeeze can also assume an indirect form and operate through the market mechanism. Within a market-oriented and relatively perfectly competitive set up the commercial family farmer operates like a capitalist. Farmers use new technologies to keep cost down. This enables the industrial sector to get more and more supplies of food at lower and lower prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) The Expenditure Squeeze:

The deterioration of the terms of trade is one reason for the relative decline of the agricultural sector. The pressure of a competitive system and a rapidly advancing technology is the other. Farmers who do not adopt and exploit new methods or technologies will either have to drift to the city to join the ranks of the urban employed and the slum-dwellers or become the people who were left behind and descend into the lost world of non-commercial (subsistence) farming. This constitutes the basis of what W.F. Owen calls “the expenditure squeeze”.

The drift to the city is not costless for the agricultural sector. Indeed, the cost of rearing and educating that part of the nonfarm labour supply which originates in the farm sector represents a ‘capital’ transfer from agriculture to industry.

This can amount to a substantial outflow of capital. Second, in serving as the residual employer, the agricultural sector maintains at its own expense redundant quantities of labour until they are able to get alternative employment opportunities in the industrial sector.

This is especially true for countries where the extended family system is a prevalent as an institutional arrangement. In such countries, the agricultural sector operates as an informal unemployment insurance and social welfare system.

Thus there are three aspects to the double developmental squeeze on agriculture. First, the sector is squeezed for the direct flow of capital, represented by the net balance of purchases and sales of the agricultural sector.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The capital flow from agriculture is measured by the difference between the total sales of agricultural products and total purchases of industrial products. Second, it is squeezed by the deteriorating domestic terms of trade. Third, it is squeezed by the transfer of human capital through migration. So the total contribution of agriculture to capital formation in industry includes the invisible as well as visible real capital flows.

Sectoral Articulation:

The supply of purchased inputs and the demand for agricultural output shows the linkages between agriculture and industry and thus show the interactions between the two broad sectors of the economy.

The sectoral articulation, that is, the interdependence between agriculture and industry, gets reflected in three linkage effects:

(1) The inter-industry linkage effect which refers to the effect of a one-unit increase in autonomous portion of final demand on the level of production in each sector;

(2) The employment linkage effect, which, as one part of the more general concept of the primary factor linkage effect, measures the total use of labour in any one sector as a result of a one-unit change in the autonomous portion of final demand and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(3) The income generation linkage effect, defined as an effect on income of the exogenous change in final demand.

An autonomous increase in one unit of final demand increases the level of production within each sector through the inter-industry linkage effect and the level of employment through the employment linkage effect. The increase in output and employment arising from these labour incomes, which through the income generation linkage, lead to increased demand for consumer goods, including more output and employment.

Inter-Industry Employment and Income-Generation Linkage Effect:

The inter-industry linkage has three components: the backward linkage effect, the forward linkage effect and the total linkage effect. The two former describe the direct effect (backward to the sectors providing inputs for the sectors and forward to the sectors utilizing the output of the sector) that result from a one-unit increase in final demand in one sector.

The direct linkages, backward and forward, capture only part of the interactions between industries. They measure only the first round of effects of the interrelationships. The total inter-industry linkage effects are those which combine both the direct and indirect repercussions of an increase in final demand. The inter-industry linkage effect of agriculture is relatively low compared to that in industry.

Besides final demand, another element reflected in the market contribution of the sectoral articulation approach, is the interaction through the market for intermediate products. In this regard, one should consider the demands of agricultural sector for intermediate capital goods, for manufactured inputs and for raw materials. The sectoral articulation approach is especially relevant when the employment and income distribution aspects of economic development are emphasised.

No doubt the policy implication from computing linkages effect and linkage potentials would vary, depending on the circumstances of the country to which the analysis is applied. If employment creation is important, agriculture should command special interest in development planning.

A high-income-generation potential is consistent with policies that promote income distribution. On the other hand, high-income generation linkage depends on high marginal propensities to consume, which may result in low rates of growth.

Finally, since linkage potential does not account for possible supply constraints and, since supply shortages may be more chronic than deficiencies of demand in LDCs, high-income-generation potential may lead to excess demand and inflation—an increases in prices instead of increases in real output.

No doubt today’s developing countries have access to foreign capital. In spite of this, they have to rely heavily on extracting the surplus from agriculture to finance industrialisation. If farmers are unable to save much to make adequate funds available for financing industrialisation it becomes necessary for a government to extract savings compulsorily from the agricultural sector by taxation, without impairing the incentive to produce or slowing down productivity growth upon which a growing agricultural surplus depends.

In the Lewis model, anything which raises the productivity of the subsistence sector (average product per person) will raise real wages in the capitalist sector, and will, therefore, reduce the capitalist surplus and the rate of capital accumulation, unless it, at the same time, more than correspondingly moves the terms of trade against the subsistence sector.

Lewis holds the view that the expansion of the capitalist sector is held in check by a shortage of capital. This means that an increase in prices and purchasing power is not stimulus to industrialisation but an obstacle to the expansion of the capitalist sector.

It is not possible to reconcile this view with the common sense view that the agricultural sector provides a market for industrial goods as also the expert view of the World Bank (the World Bank Development Report 1979) that a stagnant rural economy with low purchasing power holds back industrial growth in many developing countries.

Even in 1961, Johnson and Mellor recognised this worrying feature of the Lewis model when they perceptively remarked that “there is clearly a conflict between emphasis on agriculture’s essential contribution to the capital requirement for overall development and emphasis on increased farm purchasing power as a stimulus to industrialisation.”

One possible way of resolving the conflict is to recognise the complementarity between the two sectors from the outset. In addition, there has to be an equilibrium terms of trade that balances supply and demand in both sectors.

Agriculture provides the potential for capital accumulation in industry by providing a marketable surplus. The greater the surplus, the cheaper can industry obtain food and higher the rate of saving and capital formation. This is the supply side. But industry also needs a market for its product, which, in the early stages of development, has to come largely from agriculture.

This is the demand side, and the higher the price of agricultural goods, the larger will be agricultural purchasing power. Given this conflict between low food prices being good for industrial supply and high food prices being good for industrial demand, what is required is a general equilibrium framework, where the terms of trade between agriculture and industry provide the balancing mechanism ensuring that supply and demand grow at the same rate in each sector.

Need for a General Equilibrium Approach:

There is the need to approach development within an integrated and general equilibrium framework, rather than in terms of partial analysis. General equilibrium approach shows that the increase in the price of output, for example, leads to an increase in output supplied and labour demanded at the household level. An increase in the price of output leads to a decrease in the equilibrium level of both output and employment.

Limitation of Our Approach:

Our analysis of the interdependence between agriculture and industry is, however, not without its shortcomings. Most notably, the analysis has been overly static, and the treatment of the industrial sector has been cursory.