Disinflation and the Sacrifice Ratio!

Most people do not like inflation.

Inflation has adverse political implications also. In the past, many governments have lost power due to their inability to keep inflation under control.

This is why it is the objective of any government policy to keep inflation under control so that the voters can breathe more freely.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, at times, the cure is worse than the disease! And the neglect of indirect effects is the common source of all fallacies.

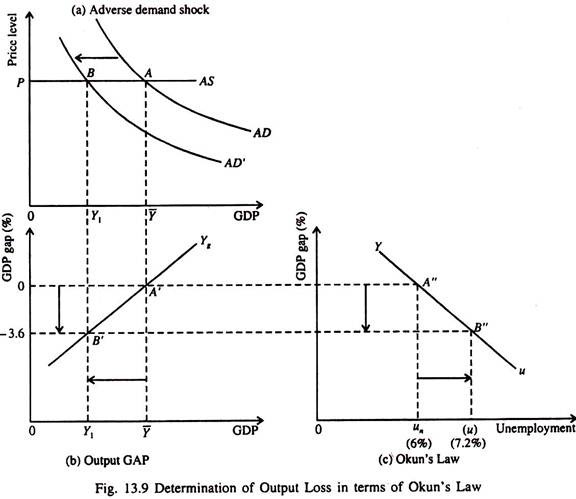

Let us suppose a government reduces the money supply to bring the inflation rate down. The Phillips curve shows that in the absence of a beneficial supply shock, such a policy will increase the unemployment rate. Consequently output will continue to fall during the transitional period.

The magnitude of output loss during the transition to lower inflation is measured by the sacrifice ratio, which is the percentage of a year’s real GDP that has to be given up to reduce inflation by 1%. In terms of Okun’s law, reducing inflation by 1% requires about 2% of cyclical unemployment.

If reducing inflation this year by 1% requires a sacrifice of 4% of current year’s GDP, reducing inflation by 3% requires a sacrifice of 12% of a year’s GDP. And this requires tolerating 8% more of cyclical unemployment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A rapid disinflation would lower output by 6% in 2 years. A moderate disinflation would lower output by 3% in 4 years. And a very gradual disinflation would depress output by 1.2% in a decade.

Rational Expectations and the Possibility of Painless Disinflation:

An alternative approach to adaptive expectations has been suggested, viz., rational expectations. The rational expectations hypothesis was popularised by Muth and Lucas. The basic idea is simple enough. Lucas assumes that people make optimal use of all the available information — including information about current government policies — to forecast the future.

Since the current rate of inflation is largely influenced by monetary and fiscal policies, expected inflation should also depend on the effectiveness of current demand-management policies. The theory of rational expectations suggests that a change in monetary or fiscal policy will change people’s expectations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So an evaluation of any policy change has to be based on the effect of such change on people’s expectations. And, therefore, any policy change has to be evaluated by taking into account the effect of policy change on expectations. If people do form their expectations rationally, then the inflation inertia will be less intense than it appeared initially.

The supporters of rational expectations argue that the short-run Phillips curve fails to represent clearly and accurately the options open to the policymakers. If people see that the policymakers always keep their commitments, then they will reduce their expectations of inflation as soon as the policymakers are credibly committed to keep the inflation rate down.

If the policymakers have the reputation of keeping their commitments, the inflation rate may drop without a rise in unemployment or a fall in output. Thus the short-run philips curve trade off does not hold under the expectation hypothesis. Under a credible policy, the sacrifice ratio will be very small.

The problem of maintaining price stability in the face of price shocks is inseparably linked up with an alternative type of price stabilisation problem, viz., bringing down the rate of inflation when it has become too high and has become incorporated in people’s expectations and firms’ price-setting behaviour.

This is known as the problem of disinflation, that is, bringing down the rate of inflation. Developing a disinflation policy requires close attention to the role of expectations in the Phillips curve.

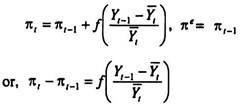

The Phillips curve equation can be alternatively expressed as

The most challenging problem of disinflation occurs when the expected rate of inflation equals the last year’s inflation rate, πe = πt-1. With this inflationary expectation, the only way that inflation can be reduced is by permitting actual output Y to fall below its potential level Y̅t.

This is termed painful disinflation. The above equation states that the change in the rate of inflation over its previous level (πt-1) depends on the percentage deviation of actual GDP from its potential level. Here

The Phillips curve tells us that, if the policymakers consider the inflation rate as too high and has to be reduced, then some sort of a recession is inevitable.

The basic policy question related to disinflation is:

How deep and prolonged the recession should be? So, the pertinent question here is: How strongly should the policymakers use the policy instruments to bring about such a path for real GDP which is consistent with the ciesired reduction in inflation rate?

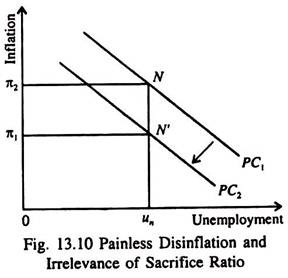

There are two requirements of painless disinflation. First, the policymakers should announce their plan(s) to bring inflation rate, down before workers and business firms, who set wages and prices, have formed their expectations. Secondly, the workers and firms have to take the announcement at face value. (Reputation is a big factor here.)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Otherwise, they are unlikely to revise their inflationary Expectations downward. If both requirements are fulfilled, there the short-run Phillips curve will shift downward. This implies that the inflation (Un) rate will fall from π1 to π2 even at the same rate of unemployment as Fig. 13.10 shows.

Since expectations of inflation influence the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment, the credibility of monetary or fiscal policy to reduce inflation largely affects the social cost of the policy change. However, in reality most people do not view the announcement of a new policy as credible.

Hysteresis and the Challenge to the Natural Rate Hypothesis:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The modern theory of business cycles (or short-run economic fluctuations; is based on the natural rate hypothesis which simply states that fluctuations in AD affect employment and output and employment only in the short run. In the long run, the economy returns to the full employment level of output as in the classical model where the AS curve is vertical due to automatic full employment.

The natural rate hypothesis — which separates short-term and long-term developments in the economy — is an extension of the classicists’ view — the dichotomy between real sector and the monetary (financial) sector.

Some modern economists have argued that even in the long run there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment because AD may affect output and employment. They explain this by referring to hysteresis, which describes the permanent effect of history on the natural rate of unemployment. This may have long-term effects on the economy by altering the natural rate of unemployment.

There are two reasons for this:

Firstly, a frictional unemployment recession may permanently demoralise workers and discourage them to search out new jobs even when the recession is over. It is because they lose their valuable skills during the transition from recession to recovery.

So a recession may increase the magnitude of frictional unemployment. This may also happen if a recession makes a worker indifferent between working and remaining idle and thus reduce his desire to work.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Secondly, during recessions, because the unemployed may lose their status as members of trade Unions, some insiders become outsiders. Since insiders care less about high unemployment, the magnitude of structural unemployment raises.

If the minority (the insiders) care more about high real wages and less about the majority (who are jobless) then the recession may permanently push the real wage above the market clearing level.

Hysteresis increases the cost of recessions by raising the sacrifice ratio. The reason is quite obvious. Output is lost even when the disinflation is over.