Link between Fiscal Policy and Crowding Out in Trade Cycle!

Whenever a government runs a budget deficit and borrows to pay for the excess of their spending over the tax revenue it receives, the talk turns to crowding out. Crowding out takes place when expansionary fiscal policy causes interest rates to rise, thereby reducing private spending, particularly investment. This section shows how changes in fiscal policy shift the IS curve, the curve that describes goods market equilibrium.

We know that the IS curve slopes downward because a decrease in the interest rate increases the demand for investment, thereby increasing aggregate demand and the level of output at which the goods market is in equilibrium. We also know that changes in fiscal policy shift the IS curve.

The equation of the IS curve is:

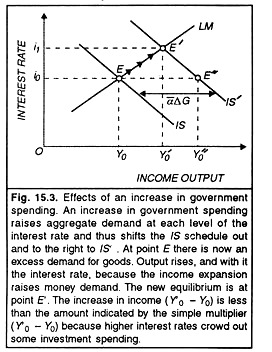

Note that G, the level of government spending, is a component of autonomous spending in relation (1). The income tax rate t is part of the multiplier. Thus both government spending and the multiplier affect the IS schedule. We now show in Figure 15.3 how fiscal expansion raises equilibrium income and the interest rate.

An Increase in Government Spending:

At unchanged interest rates, higher levels of government spending will increase the level of aggregate demand. To meet the increased demand for goods, output must rise. In fig. 15.3, we show the effect of a shift of the IS schedule.

At each level of the interest rate, equilibrium income must rise by α times the government spending. For example, if government spending rises by 100 and the multiplier is 2, then equilibrium income must increase at each level of the interest rate by 200. Thus, the IS schedule shifts to the right by 200 points.

If the economy is initially in equilibrium at point E and now government spending rises by 100, we would move to point E’ if the interest rate stayed constant. At E” the goods market is in equilibrium in that planned spending equals output. But the assets market is no longer in equilibrium. Income has increased, and therefore the quantity of money demanded is higher.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At interest rate i0, the demand for real balances now exceeds the given real money supply. Because there is an excess demand for real balances, the interest rate rises. But as interest rates rise private spending is cut back. Firms’ planned investment spending declines at higher interest rates, and thus aggregate demand falls off.

What is the complete adjustment, taking into account the expansionary effect of higher government spending and the dampening effects of higher interest rates on private spending. Figure 15.3 shows that only at point E’ do both the goods and assets markets clear. Only at point E’ is planned spending equal to income and at the same time, the quantity of real balances demanded is equal to the given real money stock. Point E’ is therefore the new equilibrium point.

The Dynamics of Adjustment:

We continue to assume that the money market clears fast and continuously, while output adjusts only slowly. This implies that as government spending increases, we stay initially at point E, since there is no disturbance in the money market. The excess demand for goods, however, leads firms to increase output, and that increase in output and income raises the demand for money. The resulting excess demand for money, in turn, causes interest rates to be bid up and we proceed up along the LM curve with rising output and rising interest rates, until the new equilibrium is reached at point E’

The Extent of Crowding Out:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Comparing E’ to the initial equilibrium at E, we have seen that increased government spending raises both income and the interest rate. But another important comparison is between points E’ and E”, the equilibrium in the goods market at unchanged interest rates. Point E” corresponds to the equilibrium where we neglect the impact of interest rates on the economy. In comparing E” and E’ it becomes clear that the adjustment of interest rates and their impact on aggregate demand dampen the expansionary effect of increased government spending.

Income, instead of increasing to the level Y”, rises only to Y’0. This leads us to the following questions. What factors determine the extent to which interest rate adjustments dampen the output expansion induced by increased government spending?

The extent to which a fiscal expansion raises income and the interest rate depends on the slopes of the IS and LAI schedules and on the size of the multiplier.

By drawing for ourselves different IS and LM schedules we are able to show the following:

1. Income increases more, and interest rates increase less, the flatter the LM schedule.

2. Income increases less, and interest rates increase less, the flatter the IS schedule.

3. Income and interest rates increase more the larger the multiplier a and thus the larger the horizontal shift of the IS schedule.

To illustrate these conclusions, we turn to the two extreme cases: one, where there is the liquidity trap and two, the classical ease where the LM curve is a vertical line.

The Liquidity Trap:

If the economy is in the liquidity trap so that the LM curve is horizontal, then an increase in government spending has its full multiplier effect on the equilibrium level of income. There is no change in the interest rate associated with the change in government spending, and thus no investment spending is cut off. There is therefore no dampening of the effects of increased government spending on income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We can easily show through the IS-LM diagrams that if the LM curve is horizontal, monetary policy has no impact on the equilibrium of the economy and fiscal policy has a maximal effect on the economy. Less dramatically, if the demand for money is very sensitive to the interest rate, so that the LM curve is almost horizontal, fiscal policy changes have a relatively large effect on output, while monetary policy changes have little effect on the equilibrium level of output.

So far, we have taken the money supply to be constant at the level M It is possible that the central bank might instead manipulate the money supply so as to keep the interest rate constant. In that case the money supply is responsive to the interest rate; the central bank increases the money supply whenever there are signs of an increase in the interest rate, and reduces the money supply whenever the interest rate seems about to fall. The more responsive the money supply with respect to the interest rate, the flatter will be the LM curve, and fiscal policy will again have large impacts on the level of output.

The Classical Case and Crowding Out:

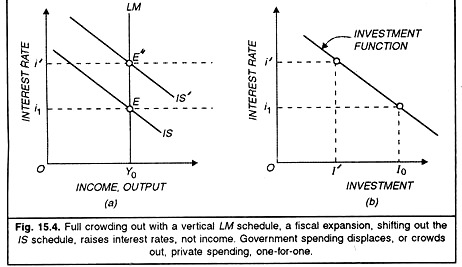

If the LM curve is vertical, then an increase in government spending has no effect on the equilibrium level of income. It only increases the interest rate. This case is shown in fig. 15 .4a, where an increase in government spending shifts the IS curve to IS’ but has no effect on income.

If the demand for money is not related to the interest rate, as a vertical LM curve implies, then there is a unique level of income at which the money market is in equilibrium. Thus with a vertical IM curve, an increase in government spending cannot change the equilibrium level of income, but only raises the equilibrium interest rate. But if government spending is higher and output is unchanged, there must be an offsetting reduction in private spending.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The increase in interest rates crowds out private investment spending. Crowding out, as defined earlier, is the reduction in private spending (and particularly investment) associated with the increase in interest rates caused by fiscal expansion. There will be full crowding out if the LM curve is vertical.

In fig. 15.4 we show the crowding out in panel (b), where the investment schedule of fig. 15.4 is drawn. The fiscal expansion raises the equilibrium interest rate from i0 to i’ in panel (a). In panel (b), as a consequence, investment spending declines from the level I0 to I’. Now it is easy to verify that if the LM schedule were positively sloped rather than vertical, interest rates would rise less with a fiscal expansion and as a result investment spending would decline less.

The extent of crowding out thus depends on the slope of the LM curve and therefore on the interest responsiveness of money demand. The less interest-responsive is money demand, the more a fiscal expansion crowds out investment rather than raising output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The view that increased government spending crowds out private spending, largely or even completely, is held by most monetarists. They believe money determines income or, as we saw above, that money demand does not depend on the interest rate, implying a vertical LM schedule. However, there is also another case where crowding out can be complete.

If the economy is at full employment so that output cannot expand, then, of course, increased purchases of goods and by the government must mean that some other sector uses less goods and services. Interest rates increase to crowd out private spending by an amount exactly equal to the higher level of government spending.

Is Crowding Out Likely?

How seriously must we take the possibility of crowding out? There three points must be made. First, in an economy with unemployed resources there will not be full crowding out because the LM schedule is not, in fact, vertical. A fiscal expansion will raise interest rates, but income will also rise.

Crowding out thus, rather than being full, is a matter of degree. The increase in aggregate demand raises income, and with the rise in income, it raises the level of saving. This expansion in saving, in turn, makes it possible to finance a larger budget deficit without completely displacing private borrowing or investment.

We can look at this proposition with the help of equation (2), which states the equilibrium condition in the goods market.

S = I + (G + TR – TA)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here the term G+TR-TA is the budget deficit. Now from relation (2) an increase in the deficit, given saving, must lower investment. In simple terms, when the deficit rises, the government has to borrow to pay for its excess spending. That borrowing “uses up” part of saving, leaving less saving available for firms to borrow to finance their investment plans.

But it is equally apparent that if saving rises with a government spending increase, because income rises, then there need not be a one- for-one decline in investment. In an economy with unemployment, crowding out is incomplete because increased demand for goods raises real income and output; saving rises and interest rates do not rise enough (because of interest-responsive money demand) to choke off investment.

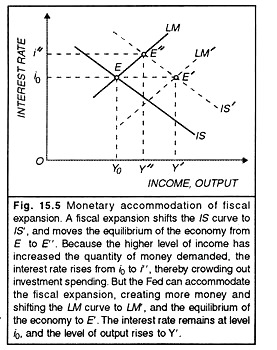

The second point is that, with unemployment and thus a possibility for output to expand, interest rates need not rise at all when government spending rises, and there need not be any crowding out. This is because the monetary authorities can accommodate the fiscal expansion by an increase in the money supply. Monetary policy is accommodating when, in the course of a fiscal expansion, the money supply is increased so as to prevent interest rates from increasing.

Monetary accommodation is also referred to as monetizing budget deficit, meaning that the Central Bank prints money to buy the bonds with which the government pays for its deficit. When the central bank accommodates a fiscal expansion, both the IS and the LM schedule shift to the right as in fig. 15.5. Output will clearly increase, but interest rates need not rise. Accordingly, there need not be any adverse effects on investment.

The third comment on crowding out is an important warning. So far we are assuming an economy with given prices. When we talk about fully employed economies, crowding out becomes a much more realistic possibility, and accommodating monetary policy may turn into an engine of inflation.