In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Cost-Benefit Analysis 2. Use of Cost-Benefit Analysis 3. Cost-Benefit 4. General Steps 5. Internal Rate of Return Approach 6. Shadow Prices and Project Evaluation 7. Importance.

Meaning of Cost-Benefit Analysis:

While taking business decisions the private firms being driven mainly by profit motive take into account only the internal direct effects (that is, cash flows accruing to them and the costs they have to incur) and do not take the longer and wider view of their activities from the social point of view. But public enterprises and non-profit institutions have to take a broader social repercussion of their resource allocation and investment decisions. That is, they take into account both internal (direct) and external (indirect) effects of their business decisions.

An analytical model called cost-benefit analysis is used to analyse the wider impact of resource allocation and investment decisions. Properly understood, it is Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of investment projects though the word’ social’ is often omitted. Thus in social cost-benefit analysis, we estimate both the direct and indirect costs of a project to the society and both the direct and indirect benefits to it. These indirect costs and indirect benefits are often called externalities. Thus social cost and benefit analysis in addition to the direct costs and benefits take into account the externalities of an investment project.

Therefore, cost-benefit analysis is especially used for analysing the desirability of public sector investment projects and programmes and is a counterpart of capital budgeting technique which is used to evaluate an investment project by a private enterprise. Explaining the essence of cost- benefit analysis Prest and Turvey who are the pioneers of the technique of cost-benefit analysis write, “Cost-benefit analysis is a practical way of assessing the desirability of projects where it is important to take a long view (in the sense of looking at repercussions in the distant future as well as the nearer future) and a wider view (in the sense of allowing for side-effects of many kinds and many persons, industries, regions, etc.), i.e., it implies the enumeration and evaluation of all relevant costs and benefits.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is important to note that in estimating social costs of a project market prices of resources are not used as they are generally distorted; they are distorted due to the imposition of taxes by the Government or due to the market imperfections or monopoly power of the resource owners. Instead, in social cost-benefit analysis shadow prices which reflect the opportunity costs or true scarcity values of the resources are used.

It is worth noting that public sector enterprises and non-profit institutions face the same problem of resource allocation and investment as the private sector. But in deciding about them while the public sector enterprises take a wider view and consider both internal and external effects (i.e., externalities) of their decisions, the private sector, guided by profit considerations alone, adopts a narrow view and takes into account only internal effects of their business decisions, disregarding the external effects which may be harmful or beneficial. Thus in cost-benefit analysis we are not concerned only with internal benefits and internal costs of an investment project to be undertaken.

Instead the cost-benefit analysis enumerates and evaluates all social benefits and all social costs of a project or expenditure programme in contrast to the capital budgeting technique used by private firms which take into account only their private costs and private benefits to judge the desirability of an investment project. Thus, to quote Todaro and Smith, “The need for social cost-benefit analysis arises because the normal yardstick of commercial profitability that guides the investment decisions of private investors may not be appropriate guide for public investment decisions. Private enterprises are interested in maximising private profits and therefore normally take into account only the variables that affect net profit receipts and expenditure. Both receipts and benefits are valued at prevailing market prices for inputs and outputs.”

According to the social cost-benefit analysis, the actual revenue or receipts from a project do not truly reflect the social benefits from a project nor the expenditure incurred on the inputs valued at market prices used as the true social costs. Besides, in calculation of social costs and benefits, the Government or planner takes into account the external effects (both external economies and diseconomies) of the public investment projects whereas private enterprise will ignore them in its evaluation of a project.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It follows from above that divergence of social costs and benefits from private costs and benefits, the investment decisions based on private costs and benefits would lead to inappropriate decisions which will therefore not maximise social welfare. Further, the approach of social cost-benefit analysis thinks that social costs and benefits can be arrived at by making suitable adjustments in market prices.

Besides, since benefits from an investment project accrue mostly in the future years and costs are also incurred for a long period in future; it is discounted social benefits and discounted social costs that are compared to decide about the desirability of a project. However, for discounting social costs and benefits of an investment project, it is social discount rate that is used to obtain the net present value rather than market rate of interest.

The Use of Cost-Benefit Analysis:

The technique of cost-benefit analysis is particularly used when a long and wider view of the effects of a particular project or expenditure programme is needed. As in case of capital budgeting by private firms cost-benefit analysis is generally used in case when the economic effects of a project or investment expenditure programme or policy change accrue in future years. However, unlike the capital budgeting by private firms, the cost-benefit analysis attempts to estimate all direct economic effects as well as indirect spill-over effects.

Cost-benefit analysis is used to assess whether a particular project or specific public expenditure programme should be accepted or rejected. In order to do so, benefits, both direct and indirect, of the project or specific public expenditure programme and similarly the costs to be incurred on the project over the years are estimated. Then the present value of both the benefits and costs over the future years are estimated using an appropriate discount rate from social points of view.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It follows from above that cost-benefit analysis is a method of evaluating public projects and investment programmes for making decisions regarding the desirability of the projects to be undertaken. Accordingly, it is used to assess big public investment schemes such as building dams and airports, controlling diseases (for example, malaria control programme), planning for defence and safety, and spending for health, education and research.

Criterion of Cost-Benefit:

Having calculated the present values of both benefits and costs at a given social discount rate, then the two are compared. If using the given social discount rate present value of benefits from a project (or other investment programme) exceeds the present value of costs, the said project or investment programme is accepted for being undertaken. On the other hand, if present value of benefits is less than the present value of costs, the proposed project or investment programme is economically inefficient and should be rejected.

Besides being used to evaluate the economic justification of the entire investment project, the cost-benefit analysis is used to determine whether the size of project under implementation be increased and if so to what extent. Such decision is usually made by using traditional marginal analysis is estimating additional benefits from the proposed increase in size and additional costs to be made.

Thus the objective of public sector decisions-making whether it is building of an airport or regulating a public utility (such as electricity generation and distribution) is wider than maximising private profits which guide private sector decision. In making a decision the Government or public enterprise has not only to consider benefits that accrue as revenue to the enterprise but also the external benefits (beneficial externalities) that accrue to other members of the society. Likewise, the cost-benefit analysis considers not only the costs that are paid by the enterprise but also the costs (including environment pollution) it inflicts on others by its activity.

General Steps in Making Cost-Benefit Analysis:

There are no simple rules or steps which government or any public authority should follow to undertake cost-benefit analysis. Through cost-benefit analysis we seek to find social profitability of a project. In the calculation of social profitability we need to measure both social benefits and social costs taking into account both direct social costs and benefits (that is, the real costs of inputs used directly in the project, and real benefits in the form of real value of outputs obtained directly from it) and indirect costs (e.g. external diseconomies) and indirect benefits (e.g. the creation of employment opportunities).

The social profitability is judged by the difference between social benefits (both direct and indirect) and social costs (both direct and indirect).

The whole process of calculating social profitability or social costs and benefits can be divided into the following four steps:

1. Specifying Social Objective Function:

The first step in making cost-benefit analysis is to specify the social objective function that has to be maximised. In this objective function the weights are to be assigned to different benefits (e.g. increase in per capita consumption, increase, in employment, desired income distribution). These weights will reflect the importance given to the various benefits of the project.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Identifying Various Benefits and Costs:

The second step in cost-benefit analysis is to identify and enumerate all benefits and costs, both direct and indirect, of investment projects. The direct benefits of a project can be measured by the extra quantity of goods and services produced if the project is undertaken compared to the conditions without it.

Thus, the direct benefits of an irrigation project is the quantity of extra crop produced net of extra costs in the form of more labour, seeds and equipment used as compared to the non-irrigated land. On the other hand, direct costs include capital costs incurred on capital equipment, machines installed, land acquired to undertake and implement the project and the operating and maintenance costs incurred over the life span of the project.

In addition to the direct effects of an investment project, there are invariably indirect or external effects. These indirect or external beneficial effects are classified into two types – (1) real or technological and (2) the pecuniary effects. The real external benefits may include reduction in costs to be incurred on other Government programmes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, the construction of an irrigation dam may lead to reduction in flooding and soil erosion which would reduce the Government outlay on flood control and anti-soil erosion programmes. Such real indirect benefits are counted in cost-benefit studies.

On the other hand, indirect (external) pecuniary benefits are not generally included in the enumeration of benefits and costs in a cost-benefit study. These external pecuniary benefits accrue in the form of increased volume of business or increase in land values as a consequence of undertaking a project.

Thus the areas in Delhi which fall near Metro railway routes have caused increase in land values in these areas. Besides, the shops and restaurants which exist in the areas surrounding the metro lines have found increase in the volume of their business. These indirect or external pecuniary benefits are distributional and not counted in cost benefit studies of Metro-railways.

Similarly, indirect multiplier effects and induced investment effects which result from Government investment projects are also generally not counted (except in some special circumstances) since they would occur whether investment made is by the public sector or private sector.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, if the objective of Government investment programme is regional development, undertaking a local investment project may induce local investment; create multiplier effect on generation of income and employment resulting in reduction of regional unemployment. Since regional development forms a part of the social objective function to be maximised, some include them in their cost-benefit studies of regional investment programme.

3. Evaluation of Social Benefits and Costs:

The third step in the social cost-benefit analysis is to measure social values of benefits, that is, outputs (both goods and services) produced by the project and social costs of inputs used in the project.

For evaluation of outputs of goods and services their shadow prices (also called accounting prices) are used instead of their market prices. Shadow prices are used to measure social values of outputs since there is divergence of market prices from their true social values. In fact, the greater the divergence between the shadow prices and market prices, the greater the need for social cost-benefit analysis for deciding about public investment.

Similarly, in cost-benefit analysis costs are also measured using shadow prices of inputs or factors used in the project. It is noteworthy that shadow prices of inputs or factors are their opportunity costs or the values foregone by the factors and resources used for the initial capital investment and production during the life period of the project. This is because resources have to be withdrawn from other activities to the implementation of the proposed project. For example, if for undertaking an irrigation project, 50 per cent of required labour is withdrawn from the ranks of unemployed labour force.

The social opportunity cost of such labour is zero and ought to be calculated as such in cost-benefit analysis though the workers employed will be paid market wages. The same holds in case of idle land used for a project. With no alternative use, the opportunity cost of idle land is zero. This is so despite the fact that Government has actually to pay compensation to the landowners for acquiring this idle land. This compensation will affect only the distribution of benefits from the project for use of land and not the social cost of the project.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

All the benefits and costs (both internal and external) over the life span of the project have to discount to obtain their present values. In this connection a difficult decision has also to be made about appropriate social discount rate with which future benefits and costs are discounted to find their present values.

Another important issue in the calculation of social benefits and costs is in what common unit of account (also called numeraire) social benefits and social costs are measured and expressed, especially when a country has trade relations with other countries of the world and, therefore, needs to sell and buy abroad. This common unit is required to make domestic and foreign goods comparable. There are two main approaches to find the common unit of account. The first approach is UNIDO approach and the second is Little-Mirrlees approach.

In the UNIDO approach benefits and costs are measured at domestic market prices using consumption as numeraire. Besides, in this approach adjustments are made for the divergence of market prices from social values by using shadow prices of goods and factors. Furthermore, to make the domestic and foreign resources comparable, shadow exchange rate is used.

In the Little-Mirrlees approach benefits and costs of projects are measured at world prices so that they should depict the opportunity costs of outputs and inputs. The use of world prices for measuring benefits and costs helps in avoiding the use of shadow exchange rate. Further, in Little-Mirrlees approach, instead of consumption public saving in foreign exchange is used as numeraire.

That is, benefits and costs in this approach are evaluated in terms of foreign exchange equivalent. However, this does not mean that project accounts are kept in foreign currency but only that in the project appraisal report values are recorded in terms of foreign exchange equivalent so as to estimate how much foreign exchange is earned by the project.

It may be noted that in both UNIDO and Mirrlees approaches some problems of measurement are faced.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Finding Social Discount Rate:

In the cost-benefit analysis the next step is to choose an appropriate social discount rate. Since benefits from an investment project are reaped mostly in the future years and costs are also incurred for a long period in future, it is discounted social benefits and discounted social costs that are compared to decide about the social desirability of a project.

For this a social discount rate is required. The private enterprises in their calculation of commercial profitability market rate of interest are used to discount the future benefits and costs. However, for social profitability of the public sector investment, market rate of interest is not appropriate for discounting future social benefits and costs.

Now why social rate of discount differs from market rate of interest? The private individuals hope to live only a certain number of years and therefore discount the future at a higher rate which is reflected in the market rate of interest. On the other hand, since the planners or the government in developing countries would like to take a longer view and give greater importance to the consumption and welfare of the future generations, they will use a lower discount rate for discounting a stream of future social benefits and costs, both evaluated using shadow prices. Thus, Todaro and Smith write, “Social discount rate may differ from market rates of interest depending on subjective evaluation placed on future net benefits; the higher the future benefits and costs are valued in the government’s planning scheme-for example, if government also represents future unborn citizens, the lower the social discount rate will be”.

5. Decision Criteria to Choose a Project:

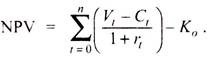

Finally, it has to be decided whether an investment project should be accepted for investment by the government or rejected. For this a decision criterion is required. The most commonly used criterion is net present value (NPV) criterion. To use this criterion we have to find the net present value of the proposed project by using the following formula-

Where, Vt is the stream of social benefits measured by using shadow prices of goods produced, Ct is the social cost of inputs measured by their shadow prices (i.e., opportunity costs), rt is the social rate of discount and Ko is the social cost of investment in the project.

Now, an investment project is economically profitable from the viewpoint of the society if the net present value (NPV) of the project using social rate of discount is positive (i.e., exceeds zero). In other words, the proposed investment project should be accepted for investment if the present value (PV) of the project exceeds the social cost of initial capital investment (K0) of the present.

Internal Rate of Return Approach:

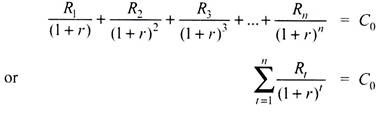

It is noteworthy that net present value (NPV) is highly sensitive to social rate of discount chosen to find the net present value. Therefore, an alternative criterion of internal rate of return is used to accept or reject a project. The internal rate of return method is also based on present value of net cash flows generated by a project over its life period. Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the rate of discount that equates the present value of net cash flows equal to the initial investment cost of the project. If R1, R2,R3, …, Rn represent the net cash flows associated with a project which have an initial investment cost equal to C0, Internal rate of return (IRR) is calculated by setting.

Solving for r, we get the internal rate of return.

It may however be noted that for social cost-benefit analysis, the initial cost of the project and return in the form of value added by the production of goods and services by the project over a number of years are calculated using shadow prices of goods and resources.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Decision Rule:

According to internal rate of return (IRR) method, if the internal rate of return (r) of a capital project is greater than the cost of capital, investment in the project should be made. If the internal rate of return (r) is less than the cost of capital, the project should be rejected. When the internal rate of return from a project exceeds the cost of capital, it will increase the value of the firm and is, therefore, worthwhile to make investment in the project. For instance, if the use of funds costs 12 per cent per annum (that is, cost of capital is 12 per cent per annum) to a society and if internal rate of return from the project is 15 per cent, the project should be accepted for investment.

It may however be noted that it is not easy to calculate internal rate of return when the life of a project exceeds one year. Fortunately, these days electronic calculators are available with which we can easily calculate internal rate of return from the data. Further, calculations of present values and internal rate of return can be done using personal computers through simple computer programmes such as Lotus 1-2-3 or Microsoft Excel.

Choice among Several Investment Projects:

The method of internal rate of return can also be used to make a choice among several projects. This issue is faced when a firm has limited funds for making investment. To decide about choosing among alternative investment projects on the basis of the criterion of internal rate of return, internal rates of return (IRR) are calculated from the cash flows of various available projects. Then, in terms of the magnitudes of internal rate of return of the various projects can be given rank-ordering from the highest rate of return to the lowest rate of return. Then investment funds should be employed to those projects which yield highest possible rates of return from the given limited available funds.

Shadow Prices and Project Evaluation:

In free market economies allocation of resources among different projects is made through market mechanism and is based on market prices of goods produced by the projects and market prices of factors used in them. However, in developing countries there are many imperfections in the markets for goods and factors and therefore market prices of goods and factors do not reflect their true social benefits and social costs of various investment projects. It is the distortions in goods and factor markets that cause divergence of market prices of goods and resources from their real social values and costs.

Therefore, for proper evaluation of various investment projects require their social cost- benefits analysis. Thus, for optimum allocation of investible resources among competing projects require adjustment or correction of market prices of goods and factors so that they should reflect their true social costs and benefits. Therefore, in evaluation of investment projects, economists use shadow prices of factors or resources and goods.

Little and Mirrlees who have made significant contribution to social cost-benefit analysis of projects write, “The whole point of shadow prices is indeed that it shall correspond more closely to the realities of economic scarcity and strength of economic needs than will guess as to what future prices will actually be.” E.J. Mishan in his theory of ‘social costs and benefits’ gives a simple and general definition of shadow prices. He writes, “A shadow or accounting price is the price the economists’ attribute to a good or a factor that is more appropriate rate for the purpose of economic calculation than its existing price, if any.”

But what are more aspirates for economic appraisal of investment projects is a subject of severe controversy. Many economists define shadow prices in terms of opportunity cost of a factor or good. Thus, G. Meier writes- “Shadow prices are determined by the interaction of the fundamental policy objectives and the basic resource availabilities. If a particular resource is very scarce (that is, many alternative uses are competing for that resource), then its shadow price or opportunity cost (the foregone benefit in the next best alternative that must be sacrificed) will tend to be high. If the supply of this resource were greater, its opportunity cost (or shadow price) will be lower in less developed countries, imperfect markets may cause a divergence between market and shadow prices. Such divergences are thought to be particularly severe in the markets for three important resources- labour, capital, and foreign exchange.”

A private firm while evaluating the projects for investment will attempt to maximise possible future profits from its given resources. Its appraisal of various projects is based on market prices of goods and resources and therefore evaluation of projects for the purpose of investment in it is called ‘Commercial Project Appraisal’.

On the other hand, the government or planner in a developing economy is concerned with maximising its social objective function and is therefore concerned with social costs and benefits and therefore its appraisal of projects is based on shadow prices (or opportunity costs) which truly reflect the social costs and benefits of the projects.

Therefore, the project appraisal by the government or planner based on shadow prices reflecting real social costs and benefits is called ‘Economic Appraisal of the Projects’. Project appraisal through opportunity costs or shadow prices is an important tool to allocate investment resources optimally in developing countries.

Opportunity Costs as Shadow Prices:

Let us explain the relevance of the concept of opportunity cost in economic appraisal of the projects. When any project uses goods and resources, it deprives them to others. For examples, a project to construct a dam, it will use saving that could otherwise be invested in textile industry or in building rural roads. Similarly, as decision to invest in the expansion of cotton textile industry will need more cotton for its production and this cotton could have been exported to earn foreign exchange.

Likewise, labour used for the construction of a dawn might have been employed in the textile industry. It is thus obvious that goods and resources used in one project can be used in alternative projects in the economy.

The concept of opportunity cost implies the value of net benefits of these resources in alternative projects that have to be sacrificed for their use in a particular project. The shadow prices reflect the opportunity costs of factors or resources used in any investment, project. Three important resources whose shadow prices need to be explained in detail are- labour, capital and foreign exchange.

Opportunity Cost of Labour:

In a developing economy with a dual economic structure, there exists surplus labour in agriculture. For an industrial project if labour is withdrawn from agriculture, the opportunity cost of labour is the loss of output in agriculture as a result of withdrawing an additional worker from it and employing him in the industrial, project. Since it is assumed by many economists that there prevails underemployment and disguised unemployment in agriculture, marginal product of a worker in agriculture, is very low or even zero.

On the other hand, when a worker withdrawn from agriculture, is employed in the industry, he will get a market wage rate equal to his marginal productivity in the industry which is much higher than the loss of output in agriculture caused by his withdrawal from it. Thus the opportunity cost of labour or its shadow wage rate employed in the industrial project in a labour-surplus developing economy is very low if not zero. This implies that social cost of labour in the industrial project will be much lower than the market wage rate. This will result in greater net social benefits over cost and will go in favour of the project being selected for investment.

Shadow Exchange Rate:

The other important example of shadow price relates to the foreign exchange rate. In general, in the developing countries the shadow exchange rate tends to be higher than the official exchange rate of domestic currency. This is the result of imposition of high tariffs and quotas on the imports of goods in the developing countries and the avoidance by them to devalue their currencies despite the rise in domestic prices of goods in them due to rapid inflation.

This overvaluation of domestic currency discriminates against the export sector that earns more foreign exchange and favours the import substituting industrial projects. To put it in general terms, the higher shadow exchange rate of a domestic currency will tend to raise the net cash flows of projects that earn more foreign exchange than they use and those import-substituting projects that save more foreign exchange than they use. In terms of net discounted cash flows from projects, the use of lower shadow exchange rate for evaluation of the projects will yield a higher net present value of the project and therefore will be preferred for investment.

Social Discount Rate:

The social discount rate, according to one view, should be to take the marginal rate of return on private capital as a measure of opportunity cost considering that investment in a public sector project must earn at least the rate of return earned by the private sector which is to be replaced by the public sector investment projects. This gives the social discount rate of 10 to 15 per cent for most of developing countries.

In view of the present author, though this approach considers capital as a scarce factor, it yields a higher discount rate and is advocated on the ground that public and private sectors compete for funds and therefore public investment must yield benefits at least equal to the rate of return earned by the private investor which is replaced by the public sector in a planned mixed economy, However, this is not good as the public sector should not aim at maximising rate of return but should pursue maximisation of social welfare.

The second approach to measure social discount rate at which the government or planner wishes to discount the future benefits is determined by the rate at which the marginal utility of public saving declines. This shadow or accounting rate of interest should equal the rate of return on public money. This gives a lower discount rate but involves a higher shadow price or social cost of investment in a project. However, in actual practice, the social discount rate is determined by trial and error method so that its value is such that it does approve more projects that are beyond the investment budget of the government or the planning authority.

It follows from above that finding an appropriate social discount rate is a very ticklish and difficult task. One thing is certain that social rate of discount should measure social time preference for current and future consumption and therefore depends on the subjective evaluation placed on future net benefits by the government or the planner. Thus Todaro and Smith write, “Social discount rates may differ from market rates of interest (normally used by private investors to calculate the profitability of investments) depending on the subjective evaluation placed on future net benefits. The higher the future benefits and costs are valued in the government planning scheme for example, if government also represents future unborn citizens, the lower the social discount rate will be.”

Decision Rule Regarding Project Selection:

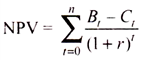

To decide whether a public project should be selected or rejected- the net present value (NPV) of stream of future benefits and costs of the project is calculated using the shadow prices of resources and social discount rate as given by the following formula-

Where Bt is the future estimated benefits and Ct is the estimated future costs both using shadow prices, r is the social discount rate and n is the number of years representing the life of the project. (Note that Ct above includes the cost of initial investment in the project.) If the net present value (NPV) of the project is positive, it should be accepted for public investment and if its net present value is zero or negative, it should be rejected.

Implementation of Shadow Price in the Real Economy:

Now, an important issue is how to implement the shadow prices in the real economy where both the public and private enterprises work. The evaluation of projects on the basis of shadow prices and undertaking those projects that pass the net present value criterion poses a difficult problem for its actual implementation. This is because shadow prices exist only on paper and are used only for evaluating the social desirability of projects.

In the real economy, a public or private enterprise which actually undertakes a project has to pay market prices for the resources used by it. Therefore, to be financially viable, it must earn profit at market prices. This makes the implementation of shadow prices difficult in actual practice. For example, if the government or a planning authority in a labour- surplus developing country has found a cotton textile industrial project as a desirable one on the basis of cost-benefits analysis using low shadow wage rate.

However, whether a public or private enterprise which executes the project will have to pay higher market wage rate to the workers rather than low shadow wages which were merely used to judge the economic desirability of the project for maximum absorption of labour in the industry.

But the payment of higher market wage rate to the workers may cause the enterprise to suffer losses. Of course, a private enterprise will never undertake such a project however economically desirable it may be on the basis of social cost-benefit analysis. However, if the government wants the project to be undertaken as it generates more employment for labour, it will have to compensate the enterprise. The effective way of compensating the enterprise will be to give a wage subsidy equal to the difference between the shadow wage rate and market wage rate that the enterprise actually pays. The payment of wage subsidy to the enterprise will make the project commercially sound and will therefore provide incentive to the enterprise to undertake it.

It follows from above that the projects that are approved on the basis of social cost-benefit analysis using shadow prices require payment of subsidies by the government. It is this reasoning that lies behind the payment of subsidies on the fertilizers, petroleum products by the government in India as they are sold to the people at prices cheaper than the market prices.

Importance of Cost-Benefit Analysis:

Social cost-benefit analysis is highly significant for development planning in developing countries. The significant benefit of cost-benefit analysis is that it can guide investment decisions, especially for the public sector. Given the constraint of resources, on the basis of cost-benefit analysis, the Government can choose the most beneficial among them. The Government can use the social cost-benefit analysis even for evaluating the effects of private investment projects. This helps the Government for formulating its policies to either support or discourage private investment.

The Government can support private investment projects by providing subsidies or provide financial support through financial institutions. The Government can discourage them by imposing taxes if the social costs exceed social benefits of the private investment.

The significance of cost-benefit analysis can be better recognized when we consider that alternative method of resource allocation-is market mechanism which uses market prices of goods and services which do not reflect true social benefits and costs of investment projects. As social cost-benefit analysis takes into account wider and broader social benefits and costs incorporating both the direct and indirect effects of an investment.

To quote Thirlwall, “The technique of cost-benefit analysis is recommended for the appraisal of publicly financed projects in order to allocate resources in a way that is most profitable to the society, recognising that the market prices of goods and factors of production do not necessarily reflect their social values and costs respectively and given that the society is concerned with the future level of consumption as well as the present, the level of current saving may be suboptimal.”

Ensuring Optimal Use of Scare Resources:

Planning in developing countries requires a lot of investment in infrastructure and heavy projects such as building of highways, airports, irrigation dams and canals, steel plants and communication network. These projects have indirect beneficial effects which are crucial for acceleration of economic growth and generation of employment opportunities. However, these investment projects require not only financial resources which are scarce in developing countries but also foreign exchange, skilled or technically trained manpower, a lot of energy resources (such as coal, petroleum oil).

The desirability of the investment of these investment projects relating to infrastructure and basic heavy industries cannot be analysed on the basis of market prices of goods and factors. Hence cost-benefit analysis which uses shadow prices reflecting opportunities costs or true scarcity values of resources used in investment projects is essential for optimum use of scarce resources in development planning.

Importance for Planning:

Cost-benefit analysis is of vital importance in economic planning for growth and employment generation in developing countries. It is on the basis of cost-benefit analysis that those investment projects are chosen in a five year plan which help in achieving the objectives of the plan. Since through cost-benefit analysis different investment projects are ranked in accordance with their contribution to the plan objectives relating to GDP growth and employment generation, priorities can be assigned which projects be undertaken in a plan period. Little and Mirrlees consider the appraisal of various investment projects on the basis of cost-benefit analysis as a sine quo non-economic planning for development.

Besides, cost-benefit analysis helps in promoting social interest rather than any sectional or group interest. If the projects are selected on the basis of social cost-benefit analysis, it becomes difficult for any vested interests or groups of the people to oppose them if they do not suit their narrow interests.