In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Keynes Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest 2. Demand for Money 3. Supply of Money 4. Determination of Rate of Interest 5. Changes in Demand for and Supply of Money 6. Significance of Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest 7. Criticisms 8. Conclusion.

Introduction to Keynes Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest:

Keynes, in his book, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, has developed a monetary theory of interest as opposed to the classical real theory of interest.

It is referred to as a monetary theory because of the following reasons:

(a) According to Keynes, interest, which is a payment for the use of money, is a monetary phenomenon,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Rate of interest is calculated in terms of money,

(c) In this theory, rate of interest is determined by the demand and supply of money,

(d) According to this theory, the rate of interest can be controlled by the monetary authority.

Keynes’ theory of interest is known as liquidity preference theory of interest. Interest has been defined as the reward for parting with liquidity for a specified period. Money is the most liquid asset and people generally have liquidity preference, i. e., a preference for holding their wealth in the form of cash rather than in the form of interest or other income yielding assets.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They can be persuaded to give up some part of their cash if adequate reward is offered. This reward is paid in the form of interest. Thus, interest is the reward for inducing people to part with liquidity. The stronger the desire for liquidity, the higher the rate of interest and weaker the desire for liquidity, the lower the rate of interest.

The reason for liquidity preference or holding wealth in cash is that future is uncertain and full of risks and cash provides protection against future risk and uncertainties. The desire to hold cash measures the extent of our distrust of our own calculations concerning future.

As Keynes writes, “The possession of actual money lulls our disquietude; and the premium which we require to make us part with money is a measure of the degree of our disquietude.” Thus Keynes, in his analysis, lays greater emphasis on the store-of-value function of money as against the exclusive emphasis of the classical economists on the medium-of-exchange function of money.

Rate of interest, like the price of any other commodity, is determined by the demand and supply of money. On the demand side, the rate of interest is governed by the liquidity preference of the community and on the supply side, it is controlled by the total stock of money as fixed by the monetary authority.

Demand for Money:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Demand for money means the desire of the people to hold their wealth in liquid form (i.e., to hold cash). People have desire for liquidity (i.e., the liquidity preference or to desire to hoard money) and interest is reward for parting with liquidity. The emphasis in Keynes’ theory is on the desire for liquidity and not on the actual liquidity.

Keynes identified three motives for the demand for money or the liquidity preference:

(a) The transactions motive,

(b) The precautionary motive and

(c) The speculative motive.

For Keynes, the total demand for money implies total cash balances and total cash balances maybe classified into two categories:

(a) Active cash balance-consisting of transactions demand for money and precautionary demand for money; and

(b) Idle cash balances – consisting of speculative demand for money.

1. Transactions Motive:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Money being a medium of exchange, the primary demand for money arises for making day-to- day transactions. In daily life, the individual or business income and expenditures are not perfectly synchronised. People receive income in periods that do not correspond to the times they want to spend it. Thus, certain amount of money is needed by the people in order to carry out their frequent transactions smoothly.

The demand for money for transactions motive mainly depends on the size of money income; the higher the level of money income, the greater the demand for transactions motive and vice versa. The transactions demand for money is not influenced by the rate of interest; it is interest-inelastic.

Symbolically, the transactions demand for money can be stated to be function of money income:

Lt = kt (Y)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

where, Lt represents the transactions demand for money, kt represents the fraction of money income society desires to hold in cash, and Y represents money income.

2. Precautionary Motive:

Apart from transactions motive, people hold additional amount of cash in order to meet emergencies and unexpected contingencies, such as, sickness, accidents, unemployment, etc. For the households, unexpected economic circumstances affect their decision to keep money for precautionary motive. For businessmen, the expectations regarding the future prosperity and depression influence the precautionary demand for money. The precautionary demand for money depends upon the uncertainty of the future.

According to Keynes, the precautionary demand for money (Lp), like the transactions demand (Lt), is also a constant (kp) function of the level of money income (Y), and is insensitive to the changes in the rate of interest-

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Lp = kp (Y)

Keynes lumps the transactions and the precautionary demands for money together on the ground that both are fairly stable functions of income and both are interest-inelastic. Thus, the demand for active balances (L1 = Lt + Lp) is a constant (k = kt + kp) function of income (Y) and can be symbolically written as-

L1 = Lt + Lp = kt (Y) + kp (Y) = k (Y)

3. Speculative Motive:

Speculative demand for money refers to the demand for holding certain amount of cash in reserve to make speculative gains out of the purchase and sale of bonds and securities through future changes in the rate of interest. Demand for speculative motive is essentially related with the rate of interest and bond prices.

There is an inverse relationship between the rate of interest and the bond prices. For example, a bond with the price of Rs. 100 yields a fixed amount of Rs. 3 at 3% rate of interest. If the rate of interest rises to 4% the price of the bond must fall to Rs. 75 to yield the same fixed income of Rs. 3.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

People desire to have money in order to take advantage from knowing better than others about the future changes in the rate of interest (or bond prices). If people feel that the current rate of interest is low (or bond prices are high) and it is expected to rise in future (or bond prices will fall in future), then they will borrow money at a lower rate of interest (or sell their already purchased bonds), and keep cash in hand with a view to lend it in future at a higher rate of interest (or to purchase the bonds at cheaper rates in future).

Thus, the demand for money for speculative motive will rise. Similarly, if people feel that in future the rate of interest is going to fall (or bond prices going to rise), they will reduce the demand for money meant for speculative purpose.

The demand for money for speculative motive (L2) is highly sensitive to and is a negative function of the rate of interest (i); as the current rate of interest rises, the demand for money for speculative motive decreases and vice versa.

Symbolically, the speculative demand for money is expressed as:

L2 = f(i)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The community’s total demand for money (L) consists of – (a) the demand for active balances, i.e., the transactions demand for money, plus the precautionary demand for money (Lt = Lt + Lp), (b) the idle balances, i.e., the speculative demand for money (L2). Thus, all the three motives together give the total demand for money Thus,

L = L1 + L2

The demand for transactions and precautionary motives, which is more or less stable, depend upon the level of income and is interest-inelastic (L1 = k(Y)). The demand for speculative motive is a function of rate of interest and an inverse relationship exists between the two (L2 = f(i)).

Thus, the community’s total demand for money depends upon the level of income and the rate of interest:

L = L1 + L2 = k (Y) + f (i)

Liquidity Preference Schedule:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

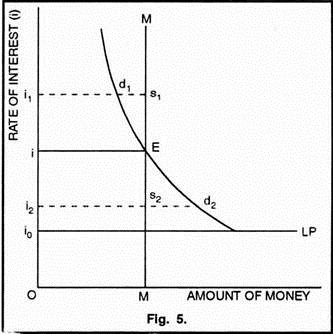

The liquidity preference schedule or demand for money curve expresses the functional relationship between the amount of money demanded for all the three motives and the rate of interest. Given the level of income, the demand for money and the current rate of interest are inversely related; as the rate of interest falls, the demand for money increases. This relationship is shown by the downward sloping LP schedule in Figure 5.

An important feature of the LP schedule is that if the rate of interest falls to a very low level (say i0). the LP schedule becomes perfectly elastic. It means that at this extremely low rate of interest, people have no desire to lend money and will keep the whole money with them. It further implies that the rate of interest cannot be lowered any more. This feature of the liquidity preference schedule has been called the ‘liquidity trap’.

Supply of Money:

Supply of money refers to the total quantity of money in the country for all purposes at a particular time. The supply of money is different from the supply of commodities; while the supply of commodities is a flow, the supply of money is a stock. Unlike the demand for money, the supply of money is determined and controlled by the government or the monetary authority of the country and is interest-inelastic (as shown by the vertical line MM in Figure 5). It is influenced by political and not by economic factors.

Determination of Rate of Interest:

The equilibrium rate of interest is determined by the intersection of the demand for money function and the supply of money function. In Figure 5, LP curve represents demand for money and MM curve represents supply of money. Both the curves intersect at point E which indicates that Oi is the equilibrium rate of interest. Any deviation from this equilibrium rate of interest will be unstable. For example, at a higher rate of interest Oi1, demand for money will be less than the supply of money (i1d1 < i1 s1).

This will cause the rate of interest to fall back to its equilibrium level (Oi). Similarly, at a lower rate of interest Oi2, the demand for money will be more than the supply of money (i2 d2 > i2 s2). This will cause the rate of interest to rise and reach its equilibrium position. Thus, the equilibrium rate of interest is determined at the level where demand for and supply of money are equal to each other.

Changes in Demand for and Supply of Money:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

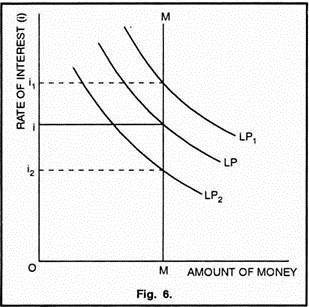

Changes in the demand for money and the supply of money lead to corresponding changes in the rate of interest. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the influence of changes in demand for and supply of money on the rate of interest.

Changes in Demand for Money:

Figure 6 shows that given the supply of money (MM curve), as the demand for money increases (shift from LP to LP1), the rate of interest rises (from Oi to Oi1) and as the demand for money decreases (shift from LP to LP2), the rate of interest falls (from Oi to Oi2). Shifts in the demand for money function (LP curve) are caused by the changes in the level of income. With an increase in the level of income, the demand for money curve shifts upwards (e.g. LP to LP1 in Figure 6) and with a decrease in the income level the demand for money curve shifts downward (e.g. LP to LP2 in Figure 6).

Changes in Supply of Money:

Figure 7 shows that given the demand for money (LP curve), as the supply of money decreases (shift from MM to M1M1), the rate of interest rises (from Oi to Oi1) and as the supply of money increases (shift from MM to M2M2), the rate of interest falls (from Oi to Oi2). But further increase in money supply (e.g. from M2M2 to M3M3) will not reduce the rate of interest anymore because of liquidity trap.

This fact has a great practical significance. By increasing money supply, the monetary authorities can reduce the rate of interest and thus encourage investment. But there is always a limit (set by the liquidity trap) to this cheap money policy.

To sum up Keynes’s theory of interest:

(a) Interest is a monetary phenomenon and the rate of interest is determined by the intersection of demand for money and supply of money;

(b) Given the supply of money, the rate of interest rises as the demand for money increases and falls as the demand for money decreases,

(c) Given the demand for money, the rate of interest falls as the supply of money increases and rises as the supply of money decreases,

(d) The rate of interest cannot be reduced beyond the lower limit set by the liquidity trap.

Significance of Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest:

Keynes’ liquidity preference theory not only provides explanation for the determination of and changes in the rate of interest, but also is of great significance in Keynes’ general theory of income and employment.

The important implications of the liquidity preference theory are given on the next column:

1. Importance of Money:

Keynes’ liquidity preference theory of interest highlights the importance of money in the determination of the rate of interest. According to this theory, interest is a monetary phenomenon and the rate of interest is determined by the demand for and supply of money.

2. Importance of Liquidity Preference:

Liquidity preference or the demand for money is of special significance in Keynes’ theory of interest. The demand for money refers to the desire-of the people to hold their wealth in liquid form (i.e., to hold cash). Keynes gives three reasons for holding cash, i.e., the transactions motive, the precautionary motive, and the speculative motive. Interest has been considered as the reward for parting with liquidity. Thus, as against the classical economists, Keynes puts greater emphasis on the store of value function of money.

3. Importance of Speculative Demand:

Speculative demand for money or demand for idle balances is the unique Keynesian contribution. It refers to the demand for holding certain amount of cash in reserve to make speculative gains out of the purchase and sale of bonds through future changes in the rate of interest.

According to the classical economists, the rate of interest is determined by the decision as to how much should be saved and consumed out of a given income level. According to Keynes, the rate of interest is determined by the decision as to how much saving should be held in money and how much allocated to bond purchase.

4. Rate of Interest and Bond Prices:

Liquidity preference theory signifies the inverse relationship between the rate of interest and the bond prices. In the security market, changes in the prices of bonds reflect themselves in the changes in the liquidity preference of the people.

An increase in the liquidity preference implies an increased desire of the people to sell bonds to get more cash, as a result of which bond prices will fall and interest rates will rise. On the contrary, a fall in the liquidity preference means an increased desire of the people to buy bonds at current prices, thus raising the bond prices and lowering the interest rates.

5. Importance of Liquidity Trap:

Liquidity trap is an important feature of the speculative demand for money function. It refers to the extremely low level of interest rate at which people have no desire to lend money and will keep the whole money with them.

At this minimum level, the rate of interest becomes sticky and the liquidity preference schedule becomes perfectly elastic. The policy implication of the liquidity trap is that the rate of interest cannot be lowered any more and the monetary policy becomes ineffective in the liquidity trap region of the liquidity preference schedule.

6. Rate of Interest-A Link between Monetary and Real Sector:

Keynes integrates the theory of money and the theory of prices and the rate of interest is the link between the monetary sphere and the real sphere.

The impact of a change in the supply of money on prices is seen via its impact on the rate of interest, the level of investment, output, employment and income. An increase in the money supply (given the LP function) reduces the rate of interest, which (given the marginal efficiency of capital function) increases investment, which, in turn, leads to an increase in output, employment and income. The prices rise because of a number of factors like the rise in labour costs, bottlenecks in production process, etc.

7. Ineffective Monetary Policy:

Keynes considers monetary policy to be ineffective during recession.

This is because of two reasons:

(a) In a recession, interest rates are already very low and the demand for holding money for speculative motive has become almost infinite (perfectly elastic LP curve). Thus, changes in money supply may cause negligible changes in the interest rates,

(b) In recession, investment plans are greatly curtailed and the demand for business loans is very low because of depressed profit expectations. This means that changes in the interest rate have very little effect on investment.

8. More General Theory:

Keynes theory of interest is more general than the classical theory. While the classical theory operates only in a full employment situation, Keynes’ theory is applicable to both full employment as well as less-than-full employment conditions.

9. Equilibrating Force:

Keynes is of the view that income and not the rate of interest is the equilibrating force between saving and investment. Rate of interest, being a monetary phenomenon, establishes equilibrium in the monetary sector, i.e., between demand and supply of money.

Criticisms of Liquidity Preference Theory:

Keynes’ liquidity preference theory has been widely criticised by economists like Hut, Hazlitt, Hansen, etc.

Main points of criticism are discussed below:

1. Real Factors Ignored:

Hazlitt attacked the liquidity preference theory of interest on the ground that it considered interest as a purely monetary phenomenon and ignored the influence of the real factors on the determination of the rate of interest. Keynes refused to believe that the real factors like productivity, time preference, etc. had any influence on the rate of interest. In this sense, the liquidity preference theory of interest is one-sided.

2. Contrary to Facts:

The liquidity preference theory goes directly contrary to the facts that it presumes to explain. According to this theory, the rate of interest should be the highest at the bottom of depression when, due to falling prices, people have great liquidity preference. But, in reality, rate of interest is the lowest at the bottom of a depression.

On the other side, according to the liquidity preference theory, the rate of interest should be the lowest at the peak of a boom when, due to general rise in incomes and prices, the liquidity preference of the people is the lowest. But, in fact, the interest rate is the highest at the peak of a boom.

3. Less Effective from Supply Side:

According to the critics, the liquidity preference theory is of limited value from supply side.

It is not always possible to reduce the rate of interest by increasing the money supply:

(a) If demand for money also increases in the same proportion in which the supply of money is increased, the rate of interest will remain unaffected,

(b) In the region of liquidity trap (i.e. perfectly elastic portion of the liquidity preference curve), the increase in the supply of money will not reduce the rate of interest any more.

4. Two – Asset Model:

The liquidity preference theory recognises only two types of assets:

(a) Money – which yields nothing exclusively;

(b) Bonds – which pay an explicit rate of interest.

All other non-monetary assets (such as, equities, physical commodities, etc.) have been assumed to be perfect substitutes with bonds. This implies that the wealth owner holds either all bonds or all money depending upon the current or expected rate of interest. Such a kind of portfolio behaviour is not observed in reality.

5. Effect of Inflation Ignored:

The liquidity preference theory ignored the effect of inflation and is based on the assumption of actual or expected price stability.

This assumption involves two problems:

(i) The assumption of price stability has two implications:

(a) Money has the absolutely certain yields of zero per cent; its opportunity cost can be measured by the money interest rate; and changes in the money rate indicate relative excess or scarcity of money supply,

(b) There is no need to distinguish between money and real rates because every change in the money rate of interest is regarded as an equivalent change in the real rate of interest.

These implications have disastrous policy consequences. For example, during inflation, high money interest rates may be mistaken as an effect of a decrease in money supply, whereas in reality they may- indicate low real rates of interest due to inflation.

(ii) The theory admits two assets (money and bonds) whose nominal value is fixed. The price inflation will then have no effect on the asset selection because the real value of each asset changes in exactly the same manner. This completely ignores the influence of inflation on portfolio decisions.

6. Limited Analysis of Monetary Impulses:

An important implication of Keynes’ theory of interest is that the monetary impulses can be transmitted to the non-monetary sector only through changes in the rate of interest, it will have no impact on the economy.

Thus, Keynes denied the fact that changes in money supply may influence the economy through direct mechanism. Moreover, the net increase in financial assets in the government budget may directly influence consumption and investment without necessarily changing the interest rate.

7. Unstable LP Function not Valid:

The Liquidity preference theory implies that monetary expansion or contraction by the authorities will have an uncertain effect on the economy because the demand for money function has been assumed unstable due to the uncertain nature of the speculative demand for money. But empirical studies have shown doubts about the validity of the assumption of unstable liquidity preference function.

8. Other Liquidity Preference Motives Ignored:

Keynes’ analysis of the liquidity preference is narrow in scope. According to him, the desire for liquidity arises only due to three main motives, i.e., the transactions motive, the precautionary motive and the speculative motive. But, the critics point out that the liquidity preference arises not only from these three motives, but also from several other factors.

Some such motives are given below:

(i) Deflationary Motive:

When prices decline, both consumers and producers have a tendency to postpone their purchases and keep large amounts of money with them.

(ii) Business Expansion Motive:

Most business companies have a tendency to accumulate and hold money balances in order to finance their plans for business expansion.

(iii) Convenience Motive:

Holding of money in the form of cash is the most convenient way of keeping one’s savings. Purchase of other assets (securities, commodities etc.) involves some kind of risk, cost of inconvenience.

9. Element of Saving Ignored:

In his definition of interest as a reward for parting, with liquidity, Keynes ignored the element of saving. Without previous saving, there cannot be liquidity (cash balances) to part with. According to Jacob Viner, “Without saving there can be no liquidity to surrender. The rate of interest is the return for saving without liquidity.”

10. Importance of Productivity Ignored:

Some critics point out that interest is not the reward for parting with liquidity as stressed by Keynes. According to them, interest is the reward paid to the lender for the productivity of capital. Thus, interest is paid because capital is productive.

11. Self-Contradictory:

The concept of liquidity preference is confusing, vague and makes Keynes’ theory of interest self- contradictory. For example, if a man holds his funds in the form of time deposits or short-terms treasury bills, he will be paid interest on them. Thus, he gets both liquidity and interest.

12. Short-Period Analysis:

The liquidity preference theory is a short period analysis since it explains the determination of interest rate in the short period. It does not tell how the rate of interest is determined in the long run.

13. Variations of Interest Rates not Explained:

This theory cannot explain why interest rates vary from person to person, from place to place and for different periods.

14. Indeterminate Theory:

Like the classical theory of interest, Keynes’ liquidity preference theory is also indeterminate. According to Keynes, the rate of interest is determined by the liquidity preference and the supply of money. The position of the liquidity preference schedule depends on the income level; it will shift up or down with changes in income level.

Thus, the rate of interest cannot be known without first having the knowledge of income level. But we cannot know income level without first knowing the volume of investment and the volume of investment requires the prior knowledge of rate of interest.

Thus the liquidity theory provides no solution; it cannot tell the rate of interest unless we already know the income level, the investment level and the interest rate itself. Thus, according to Hansen, “Keynes’s criticism of the classical theory applies equally to his own theory”.

Conclusion to Keynes Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest:

(i) Undoubtedly, Keynes liquidity preference theory of interest is an incomplete and indeterminate theory and has many other short-comings. It is for economists like Hicks and Hansen to remove these shortcomings and to combine real and monetary factors together and formulate a complete and determinate theory of interest.

(ii) However, Keynes’ theory is not without merits.

It is definitely better than the classical theory in some regards:

(a) Keynes’ theory is more realistic because he gives importance to money in his theory and considers rate of interest as a monetary phenomenon.

(b) It lays more stress on the store of value function of money and related it with future expectations.

(c) It analyses some fundamental features of money and capital markets.