In this article we will discuss about the first five-year plan:- 1. Objectives of the First Five-Year Plan 2. Outlay of the First Five-Year Plan 3. Priorities of the First Five-Year Plan 4. Financing the Plan 5. Achievements 6. Critical Appraisal.

Contents:

- Objectives of the First Five-Year Plan

- Outlay of the First Five-Year Plan

- Priorities of the First Five-Year Plan

- Financing the Plan

- Achievements of the First Five-Year Plan

- Critical Appraisal of the First Five-Year Plan

1. Objectives of the First Five-Year Plan:

The Plan had a three-fold objective:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) It aimed at correcting the disequilibrium in the economy caused by the war and the partition of the country.

(b) It proposed to initiate simultaneously a process of all round balanced development so as to ensure a rising national income and a steady improvement in living standards over a period of time.

(c) Another aim was not merely to initiate development within the existing socio-economic framework but “to change it progressively and by democratic methods in keeping with the larger ends of policy enunciated in the constitution.”

2. Outlay of the First Five-Year Plan:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Originally, the plan period for an outlay of Rs. 2069 crores in the public sector which was later raised to Rs. 2378 crores with a view to meeting the growing unemployment in the country. The expenditure actually incurred amounted to Rs. 1960 crores of which the investment component was of the order of Rs. 1560 crores.

In addition, the private sector investments amounted to Rs. 1800 crores. Thus, the total investment in the private and public sectors together amounted to Rs. 3360 crores-the annual average rising from Rs. 500 crores at the beginning of the plan to Rs. 850 crores at its end.

3. Priorities of the First Five-Year Plan:

In order of priority, the First Plan placed agriculture and irrigation first, transport and communications second, social services third, then power and finally industry. Of the actual expenditure of Rs. 1960 crores in the public sector, Rs. 601 crores (31%) went to agriculture including community projects and irrigation; Rs. 523 crores (27%) to transport and communications; Rs. 459 crores (23%) to social services; Rs. 260 crores or (13%) to power and only Rs. 117 crores i.e. (6%) to industry including village and small industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is here that the Planners exposed themselves to criticism. The amount allocated to industry was, by common consent, most inadequate. Even this partly amount was wholly allocated to consumer industries. The capital goods or even intermediate products industry was conspicous by its absence.

The Planning Commission, however, justified this order of priority on grounds of the serious agricultural crisis then facing the country, exceptionally low average food ration, and the high cost of importing foodstuffs from abroad.

The Commission was also convinced that “without a substantial increase in the production of food and raw-materials needed for industry, it would be impossible to sustain a higher tempo of industrial development.”

The importance given to transport and communications was partly explained by an effort to make rural areas less isolated and partly by the need to replace the stock and equipment worn out during the war.

Spending on health services and education was quoted as the essential point of the social services programme. These ‘technical reasons’ apart, as there was no major agrarian reform, the increase of agricultural production and revenue had to depend mainly on public outlay. Hence the precedence of agricultural development, irrigation, and transport in the priority list.

4. Financing the Plan:

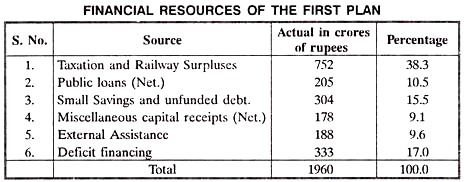

The First Plan was essentially a financial plan and not a physical plan. The emphasis, therefore, was on the fulfillment of the financial targets rather than the physical ones. The pattern of finance in the public sector shows that about 73% of the financial resources came from budgetary sources and 17% through deficit-financing.

The balance of 10% came from external sources which were mainly used for the purchase of commodities like wheat, steel and equipment required for various development projects.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As regards public borrowing, the plan target for market loans was exceeded. However, the progress in the matter of additional taxation in the states was ‘not’ commensurate with the requirements of the plans’! Their contribution fell short of the target by 34% —the actual contribution being only Rs. 269 crores as against the target of Rs. 410 crores.

5. Achievements of the First Five-Year Plan:

In the words of Shri T.T. Krishnamachari, “The First Plan was little more than a five-year budget or a five-year programme of Government expenditure —it was a Plan of preparation and as such it succeeded in a large measure.”

The National Income increased by about 18%; per capita income by 11% and per capita consumption by about 8%. As a result of various development programmes undertaken during the Plan, the rate of investment went up from 5% in the first year to 7.3% of the National Income in the last year of the plan.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A notable achievement of the plan was in the field of agriculture where overall production went up by 17%. Output of food grains increased by 20%; cotton and oil seeds increased by 45% and 8% respectively while raw jute production went up by 27%.

The country’s irrigated area increased by 31%, over 6 million acres having been brought under irrigation through major works and another 10 million acres benefitting through smaller works.

Besides, National Extension services and community projects, started for the first time in 1952, were extended to cover about 25% of the country by 1955-56. The cooperative movement spread itself to 1,20,000 villages covering about 25% of the population of the country.

Steps were also initiated for the abolition of the zamindari system which inhibited the growth of agriculture. Reform of the tenancy legislation and protection of the rights of tenants were other steps towards securing social justice.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Industrial production rose by 39% , production of Bicycles having gone up by 500%, of sewing machines by 336%, Aluminium by 97%, finished steel by 30.5%, cement by 70%, sugar by 66% and mill cloth by 37%. A number of new industries like oil-refining, ship-building, air craft manufacture, railway wagons, penicillin and D.D.T. were set up during the plan.

In the public sector, various industrial units such as the Sindri Fertilizer Factory, the Chittranjan Locomotive Works, the Indian Telephone Industry, and the Integral Coach Factory recorded progress. However, the projected Iron and Steel Plant and the Heavy Electrical Equipment Plant could not be commenced during the Plan.

The railway programme was, in the main, a rehabilitation programme. About 430 miles of lines, dismantled during the Second World War, were restored; 380 miles of new lines constructed and 46 miles of narrow gauge converted into metre gauge.

The indigenous annual production of locomotives increased from 7 in 1951-52 to 179 in 1955-56; of wagons from 3707 to 14317 and of the coaches from 673 to 1221. Total road mileage increased by about 12% but half of this represented ‘crude village paths’.

Money supply with the public increased by a little over 10% but prices at the end of the Plan were lower by 13% than at the start of the Plan. The country’s balance of payments improved at a higher level of trade; foreign exchange reserves held by the Reserve Bank went down by only Rs. 188 crores as compared to the drawing down of Rs. 290 crores envisaged in the Plan.

Indeed, few things were more impressive during 1951-56 than the handling of the India’s finances and the apparent achievement of a better balance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

6. Critical Appraisal of the First Five-Year Plan:

On the basis of these results, the Planning Commission found the overall achievements of the Plan as ‘satisfactory’. In reality, the progress was neither adequate nor substantial.

With all the publicity that went with the irrigation and power projects, the proportion of irrigated area to net sown area in 1955-56 worked out to no more than 22% as compared with 19% in 1948-49; only about 0.9% villages were electrified as against 0.5% before the Plan.

In other words, even after the completion of all the projects in hand, nearly 3/4 of the cultivated area and the bulk of the villages were at the mercy of the monsoons and ‘flickering’ lamps’. It is not surprising, therefore, that the per capita food grains production was still 7% below the 1936-1938 level and the per capita availability of cotton cloth was 10% lower than in 1945.

The railways, although reached their revised financial provision, yet ‘could not keep pace with the increase in traffic’ while road transport in the states suffered severely from the government’s greater preference for nationalisation than improvement of existing facilities. In shipping, communications, and broadcasting also, there were shortfalls.

Much more serious, from the stand point of long term development, was the shortfall in education. The % age of school going children in the age-group 6-11 years went up by 9.9% only as against the target of 18.8%. Achievement in the field of Secondary education, was smaller still. There was ‘much leeway’ to be made up as regards the supply of teachers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Land Reforms progressed from state to state at variable rates but there was little evidence to suggest that it had done much to achieve its proclaimed objective of bringing about suitable changes in the structure of the rural economy, capable of promoting rapid agricultural development.

Community development was more an act of faith since no one could “reconcile none too reliable figures of achievement from the project areas with the overall progress in different fields made in a state or in the country as a whole.”

Despite the marked increase in developmental expenditure and industrial output, the economy gave no sign of having undergone any appreciable diversification. Even within the agricultural sector, subsistence-farming of food crops continued as before. There was no perceptible shift in the crop pattern nor any significant expansion in the direction of mixed farming.

The unemployment problem, far from improving, actually worsened during the course of the Plan when the outlay had to be stepped up. As against the addition of 10 million people to the labour force, the Plan claimed to have found employment for only 4.5 million persons.

It clearly points to the fact that the pace of investment and development activity was not sufficient enough to make a decisive impact on the economy.

The secondary and tertiary sectors evidently did not grow so rapidly as to have any significant effect on the primary sector nor did the primary sector throw up surpluses which could stimulate expansion in other sectors of the economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The overall implementation of the plan was far from satisfactory. There were serious shortfalls in scheduled expenditure, the shortfall being particularly marked in agriculture and social services. On schemes for agriculture and Community Development, the Plan’s principal base, expenditure lagged by no less than 18%; for small scale industry by over 40%; for communication services, by as much as 45%.

The short fall in the case of education, housing and social services was about 11%. These short falls were primarily caused by organisational handicaps and physical bottlenecks.

Moreover, as Vakil and Brahmanand have pointed out, “the organisational mechanism of the government was so rigid as to be incapable of effectively and adequately utilizing the ‘windfall factors’ with which nature favoured the Indian economy. The food surpluses of 1953 and 1954, instead of being utilised for investment, were either frittered away in the form of a rise in the consumption standards or simply wasted”.

Unsatisfactory implementation and modest achievements apart, much of what the plan achieved was more of a ‘change gain’, than the result of any planned effort. It is generally accepted that increase in agricultural production, especially food, was “largely due to a remarkable succession of favourable agricultural seasons.”

Credit should also be given to programmes and activities of seven or eight years previous to the launching of the plan.

The emphasis on bringing more land under irrigation, the incentive of higher prices, the special efforts at improvement of techniques and input-supplies as a part of the ‘Grow More Food Compaign’ and other activities were perhaps more responsible for increasing the readiness of the cultivator to bring more land under the plough and put in his full effort.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, industrial production was encouraged due to the existence of an economic climate, itself the result of good monsoons, which encouraged industrialists to bring into production their unused capacity. A notable feature of the Plan was a general decline in the price level.

This may be attributed both to wise financial and fiscal policy internally and to subdued inflationary pressures abroad. The Government deserves full credit for this achievement but it can hardly be linked to anything that was specifically in the Plan.

The improvement in the balance of payments was also helped by a favourable international situation. The terms of trade did not turn substantially against India and the demand for export-products from India kept up well in-spite of the post- Korean war slump.

A cautious monetary and credit policy, taking full advantage of the situation, was able to keep bank rate low, government security market stable, and conserve or sparingly use foreign exchange reserves.

In short, the increase in agricultural production or improvement in the balance of payments or a decline in prices, was made possible by factors outside the plan. This led Professor, Gadgil to remark that “the major achievements of the First Five Year Plan period may perhaps be said not to have been planned at all.”

It is not to pour cold water on the Plan or imply that the plan had nothing to its credit. There is no doubt that the First Plan did lay certain foundations which, while having no immediate effect on out-put, could be of immense significance for the future. Mention may be made of the major irrigation works, the power projects, railway rehabilitation, and community development.

Besides, interesting beginnings had been made in industrial and agricultural finance in cooperative organisation, taxation policy, education, public health, and in the management and organisation of public enterprises.

Scientific and industrial research made significant progress and statistical and other data relating to Indian economy improved. These were not of much immediate significance but were in the nature of “foundations” on which the future progress could be based.

The value of planning was thus not proved by the results of the First Five-Year Plan. Many in the country, however, felt that it had been proved and the Planning Commission itself acquired status and authority in their eyes. The danger obviously was over confidence and both Government and the Commission began to display it.

The success of the First Plan suggested that a much bigger plan was possible; the comparative ease with which the economy had been activated seemed to prove that a little extra effort could achieve miracles; the degree of enthusiasm which had been generated raised hopes that such efforts could be readily stimulated. The result was an under-estimation of the tasks that lay ahead.