Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Policy in India!

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is at present very necessary for India not only for accelerating economic growth but also for meeting current account deficit which in recent years has significantly increased and is posing a serious challenge for India’s economy.

In Oct. 2012, the Parliament approved 51% FDI in multi-brand retail business. But due to stringent conditions imposed not a single company has come forward to open a multi-brand retail store.

Besides, in other fields or sectors where FDI has been permitted long ago, the caps or limits imposed are not large enough to bring FDI in adequate quantity. Therefore, in 2013 government decided to raise these caps so as to attract more foreign direct investment. There is a need for building consensus on the role of foreign direct investment in India.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In China’s success growth story, foreign direct investment has played a significant role as China has not imposed much conditions on the entry of MNCs. Rate of return on investment in both India and China are much larger compared to the home countries of MNCs and, therefore, the right policy towards FDI will go a long way in attracting FDI to finance the projects needed for economic growth and to fill the gap in our current account deficit.

To woo foreign direct investment we must give it a fair deal and ensure the security of their investment. Our treatment of FDI has not been good in the past. In the 1970s India chucked out IBM and Coca-Cola in a fit of nationalist spirit. In the late 1990s we sent back a power producing company ‘Enron’ which lost billions of dollars in setting up a power plant in Maharashtra due the differences in pricing of power generated. Recently, Sweden’s IKEA faced problems in selling Nordic Comfort food and furniture. Recent acquisitions by a multinational firm Vodafone, British mobile telecoms firm, and Dai- chi Sankyo a Japanese drug firm have recently been facing problems.

Despite the problems faced by MNCs in India, as per data furnished by the Reserve Bank of India the stock of FDI in India is now quite large equal to about $ 220 billion or 12% of our GDR This includes all things from research centers in Bangalore to cement plants.

The balance of payment data reveals that overall return on equity capital for foreign investors is probably below 10 percent and slumped in the year 2011 -12. However, balance of payments data does not fully show the rate of return earned by foreign investors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A recent survey by the RBI estimated the return on equity capital by 745 firms with a significant foreign shareholders. According to it, the overall return on equity of these 745 firms with significant foreign shareholders was 13% in the year 2010-11.

Technology firms, car makers and chemical makers did well, transport and telecoms firms less so. Unlike FDI in China, which has been directed at building factories for export, foreign direct investment into India is aimed at the domestic market—only 12% of the firms s sales were foreign.

Successful Foreign Firms in India:

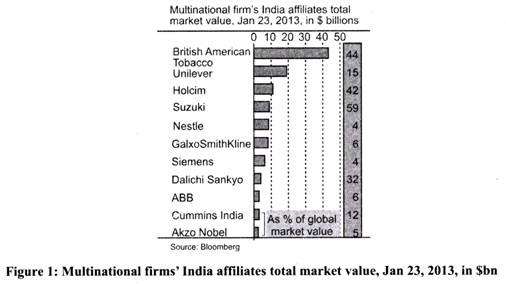

It is worth mentioning that a number of foreign firms has been highly successful and they have invested a large amount of capital and have earned a lot. These high profile firms are listed in Indian stock market while being controlled by foreign firms such as Suzuki, Nestle, Unilever and Siemens (see chart). These are well established businesses with deep roots in India and high profitability.

Foreign-controlled firms among the top 100 companies listed in India made a 24% return on equity in the year 2010-11 better than domestic firms’ returns. Their market value doubled over the five preceding years. Although the foreigners will never admit it, some of these operations have gone from backwaters within multinationals to vital sources of growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

That in turn has presented a different set of problems. Some foreign firms had the foresight to convert minority stakes in good Indian firms in to controlling ones. Suzuki took control of Maruti, India’s biggest car manufacturer by volume, in 2002. Others have failed.

After a botched effort to take control almost decades ago, British American Tabaco still owns only 31% of ITC, that has grown so fast it is now a global player in its own right. Faced with no prospect of control, some foreigners have pulled out. Honda sold its stake in Hero, an Indian motorbike-maker, in 2010 and is now competing directly against it.

Those firms that have control of fast-growing subsidiaries have been keen to boost their stakes still further. Siemens raised its stake in its unit from 55% to 75 % in 2011. But often the valuations of Indian subsidiaries are quite high. Nestle India is valued at 50 times its profits—more than double the ratio of its Swiss parent.

Faced with lower stakes than they would like, foreigners have found another, shabby way, to extract more value from their Indian subsidiaries: charging them “royalty fees”. They argue that these reflect the brand and technology benefits of being part of a global group. On 22nd January Hindustan Unilever became the latest firm to do so—announcing that the fee paid to its foreign parent would rise from 1.4% to 3.15% of sales.

The minority investors in those companies complain that they are not being given fair deal. Still, for India the trend towards higher royalty payments is a backhanded compliment, It shows that some foreign-run firms in India make heavy profits. That is why their parent companies want to grab more of them. As a signal about outsiders’ appetite for exposure to India, that may be rather important.

Latest Liberalisation of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI):

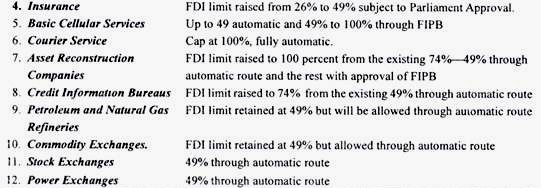

Faced with a harsh economic environment of sluggish economic growth and widening current deficit (CAD) and rapidly depreciating Indian rupee, government in its significant latest reform opened the doors to greater foreign direct investment by raising ‘caps’ on foreign direct investment in about a dozen sectors including telecom and highly sensitive sector of defence production (for state of the art technology’).

Not only have the ‘caps’ (that is, upper limits) have been raised in several sectors but the norms of their entry into India has been eased by allowing much foreign directs investment to come through automatic route, that is, without the approval of Foreign investment promotion Board (FIPs) which is a model agency to vet FDI applications in India.

Often FIPB put hurdles in the way of flowing in of direct investment. Under automatic route foreign investors will only need to make appropriate disclosures to the RBI instead of routing the investment application through FIPB. This will hasten fund flows and boost foreign investment, provided they see the possibilities of making sufficient Profits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Quick decision making, speedier implementation of decisions and non- interfering administration are vital to attract foreign direct investment which is badly needed today not only to spur economic growth and create more employment opportunities but also to meet the increasing current account deficit and to prevent the fast depreciation of rupee.

FDI cap on civil aviation has been fixed at 46%. Besides civil aviation, decision was taken on relaxing FDI caps in airports, medicine Brownfield pharma and multi-brand retail. While most of these caps can be fixed through executive orders, raising the multi-brand FDI limit in insurance requires Parliament approval.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is evident from above that intended objective of liberalisation of foreign direct investment policy is to send right signals to the existing and potential foreign investors to revive Indian economic growth which until recently was an engine for global growth. Besides spurring economic growth, the new FDI policy has been guided to meet the current account deficit and to stem the slide of the Indian rupee.

Though new FDI policy of raising FDI caps in a number of industries is a step in the right direction but more need to be done to improve India’s image as a global investment decision through speeder implementation of projects and non-interfering administration. Flowing in of much foreign investment is vital to spur economic growth and create new employment opportunities.

We need foreign investment in insurance sector to build enough capital base of the insurance companies, offer a wide range of products and protect customers’ interests against insolvency. The Indian economy battling to get out of slowdown in economic growth which is now (2012-13) down to 5 per cent is in need of resources to fund its infrastructure projects, to build highways, ports, airports and railways. Foreign funds flow will also release government resources to be spent on the infrastructure projects.

The government’s attempt to open up to more foreign direct investment (FDI) might not bring in a flood of dollars immediately but is an important policy reform. Just setting FDI limits higher is not enough to get capital flows coming in, we need better and cleaner governance at all levels. That requires political resolve at the highest level because corruption in India is systemic to how political parties are funded.