Exam questions and answers on economics!

Exam Question # Q.1. How does Managerial Economics Differ from Economics?

Ans. i. Whereas managerial economics involves application of economic principles to the problems of the firm, Economics deals with the body of the principles itself.

ii. Whereas managerial economics is micro-economic in character economics is both macro-economic and micro-economic.

iii. Managerial economics, though micro in character, deals only with the firm and has nothing to do with an individual’s economic problems. But micro economics as a branch of economics deals with both economics of the individual as well as economics of the firm.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Under micro-economics as a branch of economics, distribution theories, viz., wages, interest and profit, are also dealt with but in managerial economics, mainly, profit theory is used; other distribution theories are not used much in managerial economics, thus, the scope of economics is wider than that of managerial economics given the simplified model, whereas managerial economics modifies and enlarges it.

v. Economic theory hypothesizes economic relationships and builds economic models but managerial economics adopts, modifies, and reformulates economic models to suit the specific conditions and serves the specific problem solving process. Thus, economics gives the simplified model, whereas managerial economics modifies and enlarges it.

vi. Economic theory makes certain assumptions whereas managerial economics introduces certain feedbacks on multi-product nature of manufacture, behavioral constraints, environmental aspects, legal constraints, constraints on resource availability, etc., thus, embodying a combination of certain complexities assumed away in economic theory and then attempts to solve the real-life, complex business probable with the aid of tool subjects, e.g., mathematics, statistics, econometrics, accounting, operations research, and so on.

Exam Question # Q.2. What are the types of demand determinants?

Ans. i. Producers’ Goods and Consumers’ Goods:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Producers’ goods are also called as capital goods. These goods are used in the production of other goods. Machinery, tools and implements, factory buildings, etc. are some of the examples of capital goods.

Consumers’ goods are those goods, which are used for final consumption. They satisfy the consumers’ wants directly. Examples of consumers’ goods can be ready-made clothes, prepared food, residential houses, etc. The differentiation between a consumer good and a capital good is based on the purpose for which it is used, rather than, the good itself. A loaf of bread used by a household is a consumer good, whereas used by a sweet shop is a producer good.

Consumer goods are further classified as durable and non-durable goods. Examples of non-durable goods are sweets, bread, milk, a bottle of Coca-Cola, photoflash bulb, etc. They are also called single use goods. On the other hand, durable consumer goods are those which go on being used over a period of time, e.g., a car, a refrigerator, a ready-made shirt, an umbrella and an electric bulb.

Of course, the lengths of time for which they can go on being used vary to a good deal. A shirt may last a year or two. A car or a refrigerator may provide fairly useful service for 10 to 15 years. Old furniture can go on being used almost indefinitely so long as it is properly looked after. Durable goods are necessarily durable but not all non-durable goods are perishable. For example, coal can be stored indefinitely.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Durable Goods and Non-Durable Goods:

Durable products present more complicated problems of demand analysis than products of non-durable nature. Sales of non-durables are made largely to meet current demand which depends on current conditions. Sales of durables, on the other hand, add to the stock of existing goods that are still serviceable and are subject to repetitive use. Thus it is a common practice to segregate current demand for durables in terms of replacement of old products and expansion of total stock.

Demand analysis for durable goods is complex. Determination of demand for these goods has to take into consideration the replacement investment and expansion of the industry. The reasons for replacement investment are due to technological developments making the existing technology outmoded and the depreciation of the capital over a period of time.

Besides durable consumers’ goods, the acceleration principle is also applicable to durable producers’ goods. Suppose the demand for consumer goods expands. Then there will be a need to expand the production of capital goods in order to produce the consumer goods. Thus, if more bicycles are demanded, more machinery will be required to produce bicycles.

iii. Derived Demand and Autonomous Demand:

When the demand for a product is tied to the purchase of some parent product, its demand is called derived demand. For example, the demand for cement is derived demand, being directly related to building activity. Demand for all producers’ goods, raw materials and components are derived. Also, the demand for packaging material is a derived demand. However, it is hard to find a product in modern civilization whose demand is wholly and has supposed to have less price elasticity than autonomous demand.

iv. Industry Demand and Company Demand:

The term industry demand is used to denote the total demand for the products of a particular industry, e.g., the total demand for steel in the country. On the other hand, the term company demand denotes the demand for the products of a particular company, e.g., demand for steel produced by TISCO.

It may be noted here that within an industry, the products of one manufacturer can be substituted by products of another manufacturer even though the products themselves might be differentiated by brand names.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus an industry covers all the firms producing similar products which are close substitutes to each other irrespective of the differences in trade names, e.g., Dalda, Rath, Panghat and No.1. Obviously, firms producing distant substitutes would be excluded from the purview of the industry. Ghee and ground-nut oil, being used as cooking media, can be substitutes and will be excluded from Vanaspati industry as such.

An industry demand schedule represents the relation of the price of the product to the quantity that will be bought from all the firms. It has a clear meaning when the products of the various firms are close substitutes. It becomes vague when there is considerable product differentiation within the industry.

Industry demand can be classified customer group-wise; for example, steel demand by construction and manufacture, airline tickets by business or pleasure and geographic areas by states and districts.

From the managerial point of view, mere industry demand is not enough. What is more important is the company’s share in the total industry demand and the relationship between the two, as also the relationship between the company’s share of the demand and that of the competing firms. However, projection of the industry demand is the first step in forecasting company’s sales.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The industry demand schedule is a useful guide for studying the demand for a company’s products. The relation of the individual company’s sales to its price should be determined by the industry demand schedule. The degree of relationship will depend upon the competitive structure of the industry.

v. Short-Run Demand and Long-Run Demand:

Short-run demand refers to the demand with its immediate reaction to price changes, income fluctuations, etc. Long-run demand is that which will ultimately exist as a result of the changes in pricing, promotion or product improvement, after enough time has been allowed to let the market adjust itself to the new situation.

For example, if electricity rates are reduced, in the short-run, existing users of electrical appliances will make greater use of these appliances ultimately leading to a still greater demand for electricity. The distinction is important in a competitive situation. In the short- run, the question is whether competitors will follow suit; while in the long-run, entry of potential competitors, exploration of substitutes, and other complex and unforeseeable effects may follow.

Exam Question # Q.3. What is the relation among Average Cost, Marginal Cost, and Total Cost?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ans. Average cost is the total cost divided by the total quantity produced. Marginal cost is the extra cost of producing one additional unit.

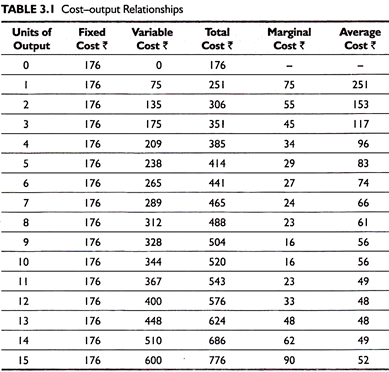

The relationship among total cost, average cost, and marginal cost is shown in Table 3.1.

A study of the above table reveals the following points:

1. Average cost is equal to total cost divided by the number of units produced. For example, at an output of 13 units, the total cost is Rs.624. Here the average cost is Rs.48.

2. The total cost is equal to the sum of fixed cost and all the marginal costs uncured. For example, at an output of 5 units, the total cost is initial cost to which the firm is committed irrespective of the quantity produced.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Where marginal cost falls, total cost will be rise at a declining rate; on the other hand, where marginal cost is rises, total cost will rise at an increasing rate.

4. When marginal cost is lower than the average cost, average cost will fall; for example, up to 12 units of output as shown in Table 3.1. This will be so irrespective of the fact whether the marginal cost is rising or falling. For example, for an output of 11 and 12 units, the marginal cost rises, but the average cost falls.

5. Where the marginal cost is greater than the average cost, the average cost will rise; for example, for outputs at 14 and 15 units.

6. If the marginal cost first falls and then rises, i.e., the marginal cost curve is U-shaped, the marginal cost will be equal to the average cost at a point where the average cost is the minimum. For example, at an output of 13 units, the average cost is the lowest at Rs.48 where the marginal cost is also Rs.48.

7. If the marginal cost is below the average variable cost, the latter will fall. This is exemplified in Table 3.1 up to 11 units of output.

8. If the marginal cost is higher than the average variable cost, the latter must be rising. This is exemplified in Table 3.1 at output levels of 13, 14, and 15 units.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

9. If the marginal cost first falls and then rises, it will be equal to the average variable cost at a point where the average variable cost is the minimum. This is so at an output level of 12 units where the marginal cost and the average variable cost are equal to Rs.33.

Exam Question # Q.4. What are the types of Postponable Costs:

Ans. Those costs which must be incurred in order to continue operations of the firm are urgent costs – for example, the costs of materials and labor which must be incurred if production is to take place.

Costs which can be postponed at least for some time are known as postponable costs, e.g., maintenance relating to building and machinery. Railways usually make use of this distinction. They know that the maintenance of rolling stock and permanent way can be postponed for some time.

1. Out-of-Pocket and Book Costs:

Out-of-pocket costs refer to costs that involve current cash payments to outsiders. On the other hand, book costs, such as depreciation, do not require current cash payments.

Book costs can be converted into out-of-pocket costs by selling the assets and having them on hire. Rent would then replace depreciation and interest. While undertaking expansion, book costs do not come into the picture until the assets are purchased.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Escapable and Unavoidable Costs:

Escapable costs are costs that can be reduced due to a contraction in the activities of a business enterprise. It is the net effect on costs that is important, not just the costs directly avoidable by the contraction. Unavoidable costs, such as labor charges, power, etc., are necessary to run the organization.

Escapable costs are different from controllable and discretionary costs. The latter are like chopping off the additional fat and are not directly associated with a special curtailment decision.

3. Replacement and Historical Costs:

Historical cost means the cost of a plant at a price originally paid for it. Replacement cost means the price that would have to be paid currently for acquiring the same plant. For example, if the price of a machine at the time of purchase, say, in 2010 was Rs.15,000 and if the present price is Rs.85,000, the original cost of Rs.15,000 is the historical cost while Rs.85,000 is the replacement cost.

4. Controllable and Non-Controllable Costs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The concept of responsibility accounting leads directly to the classification of cost as controllable. The controllability of a cost depends upon the levels of responsibility under consideration. A controllable cost may be defined as one which is reasonably subject to regulation by the executive with whose responsibility that cost is being identified. Thus, a cost which is uncontrollable at one level of responsibility may be regarded as controllable at some other, usually higher level.

Direct material and direct labor costs are usually controllable. As regards overheads, some costs are controllable and others are not. Indirect labor, supplies, and electricity are usually controllable. An allocated cost is not controllable.

Exam Question # Q.5. What is the difference between Perfect Competition and Pure Competition?

Ans. Perfect competition is often distinguished from pure competition, but they differ only in degree. The first four conditions relate to pure competition while the remaining three conditions are also required for the existence of perfect competition. According to Chamberlin, pure competition means “competition unalloyed with monopoly elements,” whereas perfect competition involves “perfection in many other respects than in the absence of monopoly”.

The practical importance of perfect competition is not much in the present times for few markets are perfectly competitive except those for staple food products and raw materials.

Though the real world does not fulfill the condition of perfect competition, yet perfect competition is studied for the simple reason that it helps us in understanding the working of an economy, where competitive behaviour leads to the best allocation of resources and the most efficient organization of production. A hypothetical model of a perfectly competitive industry provides the basis for appraising the actual working of economic institutions and organization in any economy.

Exam Question # Q.6. What do you mean by Monopoly, Pure Monopoly and Bilateral Monopoly:

Ans. Monopoly:

Monopoly is a market situation in which there is only one seller of a product. The product has no close substitutes. The cross elasticity of demand with every other product is very low. The monopolized product must be quite distinct from the other products so that neither price nor output of any other seller can perceptibly affect its price-output policy. ‘Inter alia’ it implies that the monopolist cannot influence the price-output policies of other firms. Thus he faces the industry demand curve, his firm being an industry itself.

The demand curve for his product is, therefore, relatively stable and slopes downward to the right, given the tastes and incomes of his customers. He is a price-maker who can set the price to his maximum advantage. However, it does not mean that he can set both price and output. He can do either of the two things.

His price is determined by his demand curve, once he selects his output level. Or, once he sets the price for his product, his output is determined by what consumers will take at that price. In any situation, the ultimate aim of the monopolist is to have maximum profits.

The type of monopoly described above is simple or imperfect monopoly. There is also pure, perfect or absolute monopoly to which we refer now. But we shall be concerned mainly with detailed discussion of simple monopoly and discriminating monopoly.

In pure monopoly one firm produces and sells a product which has no substitutes. The cross elasticity of demand with every other product is zero. In Triffins words, “Pure monopoly is that where the cross-elasticity of demand of the monopolist’s product is Zero.” The monopolist has absolutely no rivals. His price-output policy does not influence firms in other industries. Nor is he affected by others.

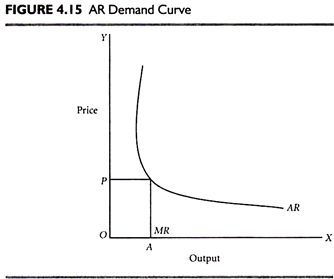

Pure monopoly “occurs when a producer is so producer is so powerful that he is always able to take the whole of all consumers’ incomes whatever the level of his output. This will happen when the average revenue curve for the monopolist’s firm has unitary elasticity (is a rectangular hyperbola) and is at such a level that all consumers spend all their income on the firm’s product whatever its price.

Since the elasticity of the firm’s average revenue curve is equal to one, total outlay on the firm’s product will be the same at every price. The pure monopolist takes all consumers’ incomes all the time.”

In Fig. 4.15, AR is the demand curve facing the pure monopolist. Since AR is a rectangular hyperbola, MR coincides with the X-axis. The monopolist can fix either price or output. If he fixes OP price, then the level of output OA to be sold is determined by his customers. If he fixes his output at OA, then price OP to be paid for that is also decided by the customers. Thus even a pure monopolist with no rivals at all cannot fix both price and output at the same time.

Since a pure monopolist earns the whole income of the community all the time, he will maximize his profits when his total costs are the lowest. It implies that his profits are the maximum when he sells a very small output, only one unit at a very high price and in the process takes away the entire income of consumers. This is, however, not possible. So, pure monopoly is only a theoretical Possibility. It has never existed and will never exist. We, therefore, pass on to the study of price-output policies under simple or imperfect monopoly.

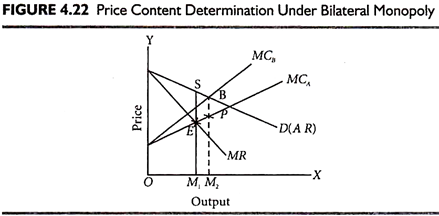

Bilateral monopoly refers to a market situation in which a single producer faces a single buyer. The seller considers himself a monopolist. So does the buyer. The problem of bilateral monopoly has two facts. The first refers to isolated exchange between two individuals completely cut off from other people.

“Price formation in the case of isolated exchange”, as stated by Edge worth, “is essentially an indeterminate problem, which is not soluble because there is an undecidable opposition of interests as each aims at the maximization of his money gain.” The second relates to the case of a single producer selling a raw material product to a single buyer who is also a monopolist in selling the finished product. Cournot offered a determinate solution to this case.

Suppose A is the single producer of bauxite, who sells it to B, who manufactures aluminium and sells it in a monopoly market. In Fig. 4.22 D is the market demand curve of B, the single buyer. D and MR are, therefore, the demand and marginal revenue curves of A, the single seller. MCa is the marginal cost curve of the single seller A which cuts the MR curve at E. The seller monopolist would like to sell OM1 output at M1S price in order to maximize his profits.

It is assumed that A regards B as one of the many buyers in a competitive market. Similarly B considers A as a competitive seller. It implies that each acts autonomously so that the MCA curve is both the marginal cost curve and the supply curve.

To maximize his profits the buyer monopolist will have a curve MCB marginal to the MCA curve to meet his demand curve D at B. He would thus be prepared to pay M2P price for OM2 quantity. The price M2p is determined by the equality of B’s marginal cost with A’s potential supply curve MCA. It leads to clash of interest because the monopoly buyer wishes to pay less price (M2P < M1S) and demands more quantity (OM2 > OM1) than what the seller monopolist is prepared to accept an offer. Thus, price and quantity are indeterminate.

Cournot, however, offered a determinate solution to this problem. According to him both the seller and the buyer monopolists would accept and pay M1S price for OM1 output because it is at this level that they maximize their profits; the seller monopolist from the buyer monopolist and the buyer monopolist from the purchasers of the finished product aluminum.

But Cournot’s solution is not regarded as correct, for the buyer monopolist possesses dual monopoly. On the one hand, he has the monopoly of buying bauxite and on the other, of selling aluminium. He would, therefore, try to extract monopoly profit from two sides. Naturally, his intention would be to pay a low price M2P and buy a larger quantity OM2 of bauxite.

The seller monopolist on his part would wish to sell a smaller quantity OM1 at a higher price OM2. The price-quantity situation is thus indeterminate and will lie somewhere between M1S and M2P price and OM1 and OM2 quantity. Indeterminacy does not imply that there is no equilibrium position and no trade takes place. Rather it means that the determinate solution to the problem of bilateral monopoly is beyond the tools of economic analysis.

Exam Question # Q.7. What are the two adjustments of Long Period Monopoly Price?

Ans. Long-run monopoly adjustments are of two types:

1. Single plant and

2. Multi-plant adjustments

1. Single-Plant Adjustment:

If the monopolist operates on a single plant there may exist three possibilities – (i) If in the short-run the monopolist is incurring losses, he may make such adjustments in his plant as to stop losses in the long-run. He may have a less than the optimum size plant in order to earn profits. If he cannot, he will have to stop production altogether (ii) He may have a plant larger than the optimum size.

This plant is, however, of less than the optimum size, for the monopoly firm is not producing at the lowest point of the LAC curve L. It has some excess capacity. It is not in a position to take full advantage of the economies of scale due to the small size of the market for his product.

In the second case the monopolist is in short-run equilibrium where he is maximizing his profits. In the long run, he changes the scale of his plant in order to earn larger profits. Accordingly, he builds the plant by adjusting its scale of plant in the long run, the monopoly firm has been able to sell more at a lower price and earn larger profits than in the short-run.

In the third case, if the monopolist tries to install a plant larger than this optimum scale plant, he will lose instead of gaining more by producing a larger output. The expansion of output beyond the optimum level would lead to diseconomies of production. It implies that producing beyond the optimum output will lead to higher per unit cost.

2. Multi-Plant Adjustments:

A monopolist may operate more than one plant. In the short-run, he can operate any number of plants of the same size or of different sizes. But in the long-run, he operates only those plants which together bring in larger profits. Given each plant of the same size and of identical cost conditions, he will have each plant of that size where the long-run average cost curve LAC and the SAC curve touch each other at their minimum points.

If in the short-run, the monopolist operates four plants, he may reduce them to two in the long-run by employing more efficient plants so that the long-run average and marginal costs are lowered and he earns larger profits. Like the single plant monopoly, the multi-plant monopoly adjustment in the long-run may be followed by quantity and price changes. But in the case of multi-plant monopoly the firm will operate at the minimum long-run average costs to gain maximum profits.

Exam Question # Q.8. What do you mean by Joint Hindu Family Firm?

Ans. In India a large number of business are carried on in the shape of Joint Hindu Family (JHF) which are in essence individual entrepreneurs possessing almost all the advantages and limitations of sole proprietorship. A JHF comes into existence by the operation of law. If the business commenced by a person is carried on by male members of his family after his death, it is a case of JHF.

Except in West Bengal where Dayabhaga system of Hindu Law is prevailing, in the rest of India Mitakshara system of inheritance is in operation according to which three successive generations in the male line simultaneously inherit the ancestral property from the moment of their birth. Thus son, grandson, and great grandson become joint owners of ancestral property by reason of their birth in the family.

They are called co-partners in interest. The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, has extended the line of co-partners interest to female relatives of the deceased partner or male relative claiming through such female relatives. The family business is included in heritable property and is thus the subject of co-partenary interest. Under the Dayabhaga Law, the male heirs become members only on the death of the father.

Father or the other senior family member manages the business and is called Karta or Manager; other members have no right of participation in the management. The Karta has control over the income and expenditure of the family and is the custodian of the surplus, if any. The other members of the family cannot question the authority of the Karta and their only remedy is to get the JHF dissolved by mutual agreement.

If the Karta has misappropriated the funds of the business, he has to compensate the other co-partners to the extent of their share in the joint property. The Karta can borrow funds for conducting the business but the other co-partners are liable only to extent of their share in the business. In other words, the liability of the Karta is unlimited.

A Joint Hindu Family can enter into partnership with others. But outsiders cannot become members of the JHF. The death of a member does not dissolve the business or the family. Dissolution of the Joint Hindu Family is possible only through mutual agreement. The male adult members can demand partition of the property of the JHF. On separation, a co-partner has no right of asking for previous accounts.

Exam Question # Q.9. What are the advantages and disadvantage of Joint Hindu Family Firm?

Ans. Some of the advantages of Joint Hindu Family firm are as follows:

1. Every co-partner is guaranteed a “bare subsistence” irrespective of the extent of his contribution to the business.

2. There is a scope for younger members of the family to get the benefit of knowledge and experience of elder members of the family.

3. Members of the family are taught to work not only for their own benefit but also for the benefit of entire family without being selfish.

4. Sick, unemployed, old, bodily infirm, widows, and orphan family members are looked after by the other members of the family with due care.

5. This form of organization provides an opportunity to develop virtues of discipline, self-sacrifice, and co-operation.

6. Benefits of “division of labor” can be secured by assigning the work to members of the family as per their specialization.

7. As “Karta” enjoys full freedom in conducting family business, he can take quick business decisions and also can run the business without interference by others.

8. As the liability of the “Karta” is unlimited, he takes maximum interest in business in order to manage it on the most efficient lines.

As against the above advantages, the Joint Hindu Family firm suffers the following disadvantages:

1. There is no encouragement to work hard and earn more, because members who work hard are not properly rewarded and all the co-partners irrespective of the work turned out by them share the benefit of their hard work.

2. As “Karta” takes the responsibility to manage the firm, the other members of the family may become lazy and inactive.

3. The “Karta” exercises full control over the entire business, and other co-partners have no right to interfere in the management of business, so this hampers the initiative and enterprise of individuals.

4. Generally, the elder members of the family may not approve the views of the younger members of the family. This leads to conflict between old and young members of the family and may result in the partition of the business.

5. Karta may misuse his freedom for his personal benefits as other co-partners have no right to interfere in conducting business.

This form of business organization is losing ground with the gradual end of the Joint Hindu Family system. It is being replaced either by sole proprietorship or partnership firm.

Exam Question # Q.10. What is the difference between Partnership and Joint Hindu Family Firm?

Ans. Though both partnership and Joint Hindu Family firm are organized by groups of persons, there are some basic points of distinction arising from the different laws governing them.

The following are the points of distinction between these two:

1. Partnership firm can only arise as a result of contract between the partners. But a Joint Hindu Family business is the creation of law; the members of the joint family become co-partners by virtue of their status.

2. A partnership is governed by the Indian Partnership Act, but a Joint Hindu Family business is governed by the Hindu Law.

3. In the case of partnership, women can become the members of the partnership business but in the case of Joint Hindu Family business only male members can become co-partners. However, under Dayabhaga system of Hindu Law which is prevailing in West Bengal, female members can become co-partners under certain circumstances.

4. In the case of partnership firm, a minor cannot become a full-fledged partner, but in the case of the Joint Hindu Family business even a minor becomes a copartner from the moment of his birth.

5. A partnership becomes illegal if the number of partners exceeds 10 in the case of banking business and 20 in the case of other business. But in the case of Joint Hindu Family business there is no maximum limit to the number of members.

6. In the case of partnership firm, though registration is not compulsory, usually all the firms are registered to get some benefits of registration. In the case of Joint Hindu Family business registration is not at all compulsory.

7. In partnership the death of a partner dissolves the partnership, but the Joint Hindu Family business is not affected by the death of a co-partner. Both partnership and Joint Hindu Family business can be dissolved through mutual agreement.

8. Every partner can take part in the management of the partnership business and any partner can bind his other partners by acts done in the ordinary course of the partnership business. But in the case of Joint Hindu Family business, only the Karta, the senior most member of the family, has the implied authority to manage the business and to bind the joint family business for all the acts done in the ordinary course of the business.

The Karta or Manager enjoys wide powers to borrow money, enter into contracts, mortgage or sell assets, or take any other action for the legitimate interest of the business.

9. The liability of partners in partnership business is joint and several to an unlimited extent. But in a Joint Hindu Family business the liability of every member except that of the Karta is limited to his interest in the joint property. The liability of the Karta is unlimited and the creditors of the firm can recover their debts even by selling the Karta’s personal properties.

10. The allocation of shares of partners in the partnership business is determined by the mutual agreement, and change in the shares of partners can take place only with the mutual consent of all the partners. In a Joint Hindu Family business, every co-partner enjoys equal share in the family business but the share of each member may fluctuate; it increases with the death of an existing co-partner and diereses with the birth of a new one.

11. If a partner dies, his interest in the partnership devolves on his heirs, whether they are admitted as partners or not. But in a Joint Hindu Family business, if a co-partner dies the undivided share of the debased co-partner devolves on the surviving co-partners and not on the heirs of the deceased by succession.

12. A partner in a partnership firm, after severing his connections, can ask for accounts of past profits and losses but it is otherwise in the case of a co-partner.

Exam Question # Q.11. What are the Problems Faced by Public Sector Enterprises?

Ans. Some of the important problems of the public sector enterprises stated above have been analyzed here and if these problems could be tackled, certainly we can expect a much higher rate of return on the investment in the public undertakings.

i. Poor Project Planning:

Due to several mistakes, flaws, and omissions in project planning, many of the public enterprises take longer time to complete, which results in increasing the cost of the project and considerable delay in their completion. For instance, the commissioning of the Tomboy project delayed by 3 years, Barony Refinery by 2 years and Antibiotic Factory at Hardware by 1 year. To overcome this drawback, adequate feasibility studies and detailed planning should be undertaken.

ii. Bad Financial Planning:

The financial planning of many public sector enterprises also suffer from several drawbacks due to which they face the problem of overcapitalization. According to the study team of the Administrative Reforms Commission, many undertakings such as Hindustan Aeronautics, Heavy Engineering Corporation, Heavy Electrical, Fertilizer Corporation, and Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals were found to be over-capitalized.

The various reasons that have contributed for over-capitalization are the inadequate planning, surplus capacity, delays in construction, heavy investment on housing and labour welfare, and bad location of projects.

iii. Heavy Overheads:

These enterprises have incurred huge expenses for the provision of amenities to the employees and townships to accommodate them. It is estimated that the average investment in township accounts to about 20% of the cost of a project.

iv. Faulty Production Planning:

Lack of proper production planning in these undertakings has resulted in the under-utilization of capacities leading to heavy losses. Further, there is absence of proper materials and inventory management and also budgetary and inventory controls. All these have affected the efficiency and the rate of return on investment.

v. Poor Manpower Planning:

Because of working estimation of manpower requirements, over-staffing is a common feature of all public enterprises leading to increase in wage bill and operating costs considerably. The Administrative Reforms Commission has observed that “a comparison of the forecast made in the detailed project report of various steel plants, fertilizer project, heavy electrical plant, etc., shows the actual staff strength is much in excess of that estimated in the project reports.”

vi. Poor Labor Management Relations:

In a majority of these undertaking industrial relations are far from satisfactory in spite of the fact that the huge sums have been spent for providing amenities to the employees. This resulted in strikes and lockouts leading to fall in output and increase in the cost of production.

vii. Problem of Personnel:

The salary and wage scale of the personnel of these undertakings are comparatively low than private sector undertakings and due to this capable people are not available. The method of recruitment and training is also outdated and faulty. Further, these undertakings continue to depend on deputationists from the cadre of civil servants for filling the middle- and top- level posts. These civil servants lack business acumen and experience, which are essential for efficient management of the undertakings.

viii. Lack of Autonomy of Management:

The government, the minister concerned, and the Parliament interfere in the day-to-day working of these enterprises and due to this interference, it has become difficult for these undertakings to run on sound business principles. For managing the units efficiently, there is need to run them on business principles and further they should be given a large measure of autonomy in the day-to-day administration.

One of the methods adopted by the government to improve the management is to establish holding companies to take over the management of some public sector undertakings. The government has already established a holding company, Steel Authority of India Ltd. (SAIL), to administer the steel units in the public sector. It has already shown good results.

In conclusion a reference may be made to the policy proposed in the Fourth Five Year Plan in relation to the operation of public sector enterprises. The policy is linked with action proposed in two separate directions. First is in the direction of much greater co-ordination and integration. Though investments in the public sector have been large and their composition varied, the different units within the sector do not act sufficiently in concert.

It is suggested that this defect can be removed by creating appropriate machinery for effective co-ordination. When this happens, the plans of individual units will become more purposeful and their operations efficient. Secondly, it is proposed that detailed decision-making in the individual units should be effectively decentralized. This is a specifically stated objective of government policy, which has yet to be attained.

Exam Question # Q.12. What are the Administrative Problems of State Enterprises?

Ans. Since independence, a large number of State enterprises have been established and the State has been facing the problems relating to their administration. The various experts’ committees that were constituted to advise the government on the management of State enterprises have given divergent and over-contradictory views.

Nevertheless, they have thrown some light on the nature of problems and have given some valuable suggestions. Without going into the details of the suggestions made by the various experts’ committees, a general reference to some aspects of administrative problems of State enterprises may be made here.

1. Choice of a Form of Organization:

In India, company form of organizations have been found favorable with the government as against the consensus of experts for public corporation. The reasons for favoring company form of organization are as follows – (i) the opportunity that it provides for attracting private investment, both domestic and foreign; and (ii) the executive arm of the government did not want the public to get the full information about the undertaking which is the case if it were a public corporation.

Prof. Galbraith in 1956 and the Estimates Committee in 1960 have recommended the establishment of larger companies in order to derive the benefits and economies of large-scale organization and management. A beginning has already been made in this corporation, the Hindustan Steel Limited, Fertilizer Corporation, and the Harvey Electrical Limited.

2. Management:

The board of directors appointed to various public undertakings are nominated by the government, mostly from the government officials of the various departments The Estimates Committee has felt that these directors cannot play any useful role. It has, therefore, suggested that the membership of the board should be closed to the officials of the departments, members of parliament, and ministers.

Krishna Mennen Committee has suggested that the directors should be drawn from the ranks of the company and should consist of financial talent, technical skill, administrative talent, and representatives of labor.

3. Autonomy:

The Estimates Committee has pointed that in India State undertaking are often treated as departments and offices of the government which are subject to all the usual red tape and procedural delays. This greatly affects the productive activity of the undertakings. They should be run on business principles and there should not be interference by the Ministers on the pretext of regulating them.

The need for autonomy of management for State enterprise has been emphasized by E.C.A.F.E. Seminar as well as by other experts’ committees, which were constituted to examine the working of public enterprises.

4. Internal Administration:

One important problem faced by the State enterprise is the lack of trained personnel to manage them. At present the managing directors are mostly the senior officers of the government departments who do not possess technical knowledge and experience.

The problem of personnel can be solved either by direct recruitment of young men through special recruitment boards or by drafting people with good record in the private sector. It is gratifying to note that recently it has been decided to create industrial management service for staffing enterprises in public sector.

5. Parliamentary Control:

As the State enterprises are set up mainly to render service to society and safeguard its interest, it is necessary that parliament should exercise some control on their working. The parliament has to see that – (a) the consumers are provided with quality goods and service at reasonable prices and (b) interest of labor is protected.

Parliamentary control over the State undertakings is exercised by the methods such as – (a) questions in parliament, (b) debates on the annual grants of the various ministers, (c) Annual reports on the government companies, and (d) Public Accounts Committee and the Estimates Committee reports.

There can be no objection to parliament’s control of State enterprises in which huge public funds are involved. However, it is necessary for parliament to allow a certain amount of flexibility in regard to control to be exercised from time to time.

6. Pricing Policy:

Another important problem faced by the administrators of public enterprises is improper pricing policy. While formulating a price policy for public enterprises, the administrators have to bear in mind many complex considerations such as generation of surplus for reinvestment, nature of demand for the products, purchasing power of consumers, policy of the State, attainment of the optimum level of production, competition from private enterprise and from foreign producers, availability of substitutes, etc.

Economists also are not unanimous in their opinion regarding the pricing policy of public enterprises. While some economists advocate that public enterprises should function in the public interest on a no-profit-no-loss basis, some others have stated that the public enterprises should be able to generate enough surpluses both for their requirements of growth, replacements and development, as well as for financing other developmental plans included in the Five Year Plans.

In this connection we may note that the Administrative Reforms Commission’s Study Team on Public Undertakings recommended that our public enterprises should pursue a pricing policy that ensures not merely that the cost is covered but also the financial requirements of other developmental plans of the country can be financed through their surpluses.

In accordance with the recommendations of the study team, the Fourth Plan gave a general direction to all public enterprises to aim at a rate of return of not less than 11-12 per cent.