Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Compilation Function’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Consumption Function’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Consumption Function

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Concept of Consumption

- Essay on the Keynesian Innovation of Consumption Function

- Essay on the Theory and Evidence of Consumption Function

- Essay on Optimising Hypothesis

- Essay on the Rational Expectations of Consumption Function

- Essay on Consumer Expenditure and Consumption

- Essay on Ricardian Equivalence

- Essay on the Real Balance Effect of Consumption Behaviour

- Essay on the Conclusion to Consumption Function

Essay # 1. Concept of Consumption:

The concept of consumption originates from the concept of demand. Demand is a key concept in both macroeconomics and microeconomics. In the former, consumption is mainly a function of income, whereas in the latter, consumption is primarily, but not exclusively, a function of production.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The theory of consumer behaviour has evolved over the last seven decades from a set of statements about how consumers allocate a given income among a set of purchased goods and services to a theory incorporating concerns about the division of income between saving and spending. Since 1936, the consumption function has developed from little more than a rule of thumb to a sophisticated empirical model of aggregate consumption expenditure.

The consumption function relates total consumption to the level of income or wealth and, perhaps, other variables. Consumption functions are sometimes defined for individual households, but their main role is determining total national consumption in a macroeconomic model.

One characteristic of the consumption function, the MPC (the responsiveness of consumption to assumed changes in income or the ratio of the change in consumption to the change in income, other things being equal) is an important determinant of the stability of the economy in a simple multiplier model. In general, the smaller the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), the more stable is the economy with respect to changes in government spending, investment, net exports, or money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Essay # 2.

Keynesian Innovation of Consumption Function:

The consumption function was introduced by J.M. Keynes as a major element in his model of income determination. Keynes (1936) introduced the consumption function as a relationship between consumption and (disposable) income. Keynes conceived of the consumption function as relating consumption to disposable income.

Although Keynes catalogued many subjective and objective factors which affect consumption, he argued that consumption depends mainly on the total net income of consumer and that the MPC would be less than the APC (the ratio of consumption to income or the average propensity to consume). The latter assertion was justified by referring to the diminishing marginal utility of current consumption at higher levels of income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Keynesian theory of consumption shows that the current level of disposable income (DI) is the central factor determining a nation’s consumption. It uses only the current income to predict consumer expenditure.

Keynes believed this income-consumption relationship to be a fairly stable one. The reason is that the current level of DI is the central factor determining a nation’s consumption. Yet substantial shifts in the function were soon observed by empirical studies. So, there was need for refinement of the Keynesian consumption function.

In larger time series, consumption seemed to vary around a constant fraction of DI. In contrast, consumption function fitted to depression era or cross-section data indicated that the APC declined as DI rose. In other words, these studies estimated that the MPC was less than APC. This is the essence of Keynes’s absolute income hypothesis.

Alvin Hansen (1939) predicted that a secular stagnation would result unless government spending filled this growing gap between output and consumption. When the gap did not seem to appear, the stage was set for a few more sophisticated techniques of income-consumption relationship. These theories are still provide strong microeconomic foundation for macroeconomics.

Essay # 3.

Theory and Evidence of Consumption Function:

One of the most debated problems with respect to the nature of the consumption-income relationship has been whether the basic relationship is one of proportionality or, as Keynes thought, and, as the data suggest, one in which the proportion of consumption to income could be expected to decline as income rose.

In 1946, Simon Kuznets published a study of consumption and saving behaviour on the basis of time series data. Kuznets’ data pointed out two important things about consumption behaviour. First, over the long run the APC showed no tendency to decline. So the MPC equaled the APC as income grew along trend.

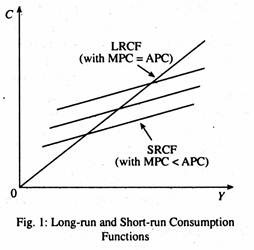

This meant that along trend the C =f (Y) function was a straight line passing through the origin, as shown in Fig 1. Second, Kuznets’s study suggested that years when the APC was below the long-run average occurred during periods of economic slump.

This meant that APC varied inversely with income during cyclical fluctuations. So, for the short period corresponding to business cycle, empirical studies show consumption as a function of income to have a slope like that of the short-run functions rather than the long-run functions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, by the late 1940s, it was quite evident that a theory of consumption must account for at least three observed phenomena:

1. Cross-sectional budget studies show APS increasing as Arises, so that in cross-section of the population, MPC < APC.

2. Business cycle, or short-run, data show that the APC is smaller than average during boom periods and greater than average during slumps, so that, in the short run, as income fluctuates, MPC < APC.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Long-run trend data show no tendency for APC to change over the long run, so that, as income grows along trend, MPC = APC.

Moreover, it was felt that a theory of consumption should be able to explain the apparent effect of wealth on consumption that was observed after World War II (1939-45). Kuznets’ time series data appeared to be consistent with the view that consumption is a stable function of income, with an MPC less than one (and equal to APC). But they were not consistent with the consumption function derived from cross-section data for the pre- World War II period.

Some reconciliation of the two sets of data was obviously required. Perhaps there existed a long-run consumption function showing a proportional relationship, and a “short-run” function involving an MPC < APC. But exactly how were the two to be related?

The first attempt to reconcile was made by Arthur Smithies. He argued that the consumption function—basically a non-proportional response of consumption to fluctuations in income— had been drifting slowly upward over the decades, as income had grown slowly, and that the upward drift of the function had just happened to offset the tendency for the APC to decline as income grew. Two reasons accounted for such drift—growing urbanisation and changes in the age composition of the population. More and more people were entering old age brackets. These people consumed but did not earn.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

James Duesenberry advocated the position that the basic relationship was one of proportionality between income and consumption. He defended this as consistent with a priori theory, including relevant borrowing from modern sociology and some of areas of psychology. Why, then, do we observe an apparent non-proportionality in the short run? This merely reflects a lag in the adjustment of consumption to short-term income fluctuations.

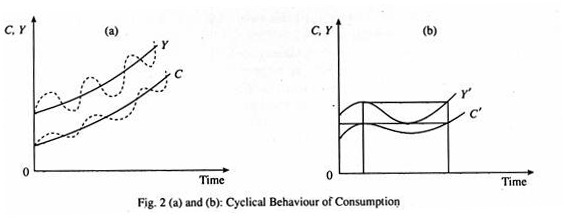

Consider Fig. 2(a). If income should grow steadily over time as shown by solid line Y, consumption would grow in the same proportion, as shown by solid line C (where C is at each time is a constant fraction of Y). But income growth is not steady; it is bunched in spurts and dips as shown by broken line Y’.

Consumption responds to these spurts and dips in income as along C’. If we view the whole history, it is obvious that consumption fluctuates in proportion to income. But if we look at any little piece of history composing only a single ‘cycle’, we lose sight of the long-run proportionality and conclude instead that the relationship is non- proportional.

The behaviour of C’ and Y’ in a single (idealized) cycle is shown in Fig. 2(b). The reason why C then follows Y in the depression, Duesenberry argued, is that consumers adjust their consumption not only to current income but to previous income, particularly previous peak income. All during the decline consumers are trying to protect their consumption standards acquired during the previous boom. As income falls, they reduce consumption as little as possible (thus reducing saving sharply).

During the subsequent recovery period, when income rises toward its previous peak level, consumption moves up slowly too, with much of the increase in income going to restore the saving rate. Only when income moves into new high ground does consumption respond more vigorously to current income. There is, in short, “a ratchet effect”. Consumers find it easier to increase consumption then to reduce it. This effect can be seen quite clearly in the C’ line of Fig. 2(a) where consumption rises almost in a stair step fashion.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Duesenberry proposed a consumption function of the following unusual form:

St/Yt = a yt/Y0 + b

where S and Y represent saving and income, respectively, the subscript t refers to the current period and 0 to the previous peak. This equation thus says that the average propensity to save (St/Yt) is a function of the ratio of current to previous income. If this latter ratio is constant, the APS is constant. But if income falls below the previous peak, the APS falls.

However, Duesenberry’s hypothesis did not stimulate further investigation of income- consumption relationship because it was not based on empirical studies. But this variant of the optimising hypothesis has withstood the test of time. The optimising hypothesis states that current consumption will be determined as part of an optimal lifetime allocation of current and future income to current and future consumption and bequests.

An increase in current or future income increases the total wealth to be allocated and so, generally, increases current and future consumption and bequests. Thus, factors which cause a persistent or permanent increase in income would have much stronger effect on wealth and current consumption than a temporary or transistor increase in income.

In this way, the optimising hypothesis suggests that the short period changes in current net income considered by Keynes should have relatively small effects on consumption—that is, the MPC for transitory variations in income.

Essay # 4.

Optimising Hypothesis:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A number of hypothesis were presented alternatives to Keynes’s AIH. Three forms of the optimising hypothesis are widely used: the PIH, the LCH, and the rational expectations hypothesis. Although they are equivalent in their most general forms, different simplifying assumptions have been used in empirical work.

The Keynesian theory of consumption shows that the current level of income is the central factor determining a nation’s consumption. It uses only the current year’s income to predict consumption expenditures. Statistical studies show that consumers generally choose their consumption levels with an eye to both current income and long-run income prospects.

In order to understand how consumption depends on long-term income trends, two path-breaking studies on long-term influences were made, one by Milton Friedman (one the permanent income hypothesis or PIH) and the other by Franco Modigliani (the lifecycle hypothesis or LCH).

While these models apparently seemed to be competing in nature, they are now treated as complementary with differences in emphasis which serve to illustrate seemingly different and yet significant problems. Both models emphasised the distinction between consumer expenditures measured by the national income accounts and pure consumption which was to be explained by Inter-temporal optimising behaviour of consuming units, or, to be more specific, by optimal allocation of present and future resources over time.

Permanent income is the trend level of income—that is, income after removing temporary or transient influences due to the weather or windfall gains or losses. According to PIH, consumption responds primarily to permanent income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, the hypothesis states that current consumption is not dependent on current disposable income (as Keynes predicted) but also on whether or not that income is expected to be permanent or transitory. According to this hypothesis, both income and consumption have two parts—permanent and transitory.

A person’s permanent income comprises such things as his long-term earnings from employment (wages and compensation), retirement pensions and income derived from the possession of capital assets (interest and dividends). The amount of a person’s permanent income will determine his permanent consumption plan, for example, the size and quality of the house he (she) will buy and long-term expenditure on mortgage repayments, etc.

Transitory income comprises short-term temporary payments, borrowing and ‘windfall’ gains from winnings and inheritances, and short-term reduction in income arising from temporary unemployment and illness. Transitory consumption such as additional holidays, clothes, etc. will depend upon the amount of this extra income.

Permanent income is a real perpetuity yield from total current wealth on the assumption that there is a constant long-term real interest rate and that consumption is proportional to wealth. Consumption is a constant fraction of permanent income, and permanent income is that interest rate times wealth.

Wealth increases over time owing to normal saving from permanent income plus the (positive or negative) windfall effect of transitory income. Transitory fluctuations in income, thus, have relatively small effects on permanent income and consumption.

Friedman’s argument is that the essential form of the consumption function is one of proportionality. Permanent consumption is proportional to permanent income. But the actual observable or measured income of any period, for any individual or an economy, consists of the sum of permanent and transitory components.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Likewise, actual measured consumption consists of its basic permanent component plus a random transitory component.

Friedman assumes (with little bias, some argue) that the transitory elements of consumption and income are uncorrected with their corresponding permanent elements, and further, are uncorrected with each other:

p (Yt, Ct) = p (Yp, Yt) = p (Cp, Ct) = 0

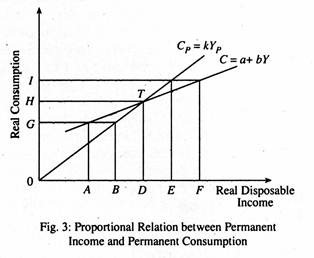

Thus the main prediction of the PIH is that there is an exact proportional relation between permanent income (Yp) and permanent consumption (Cp).

Cp = kYp

where k is the proportionality factor.

Fig. 3, which is for a cross-section of the population, shows the basic consumption function (assumed to be the same for any small sample of families) as the line Cp = kYp theory the origin. This shows the permanent consumption that would correspond to any permanent income. Income 0D is the average measured income for the whole community or mean income.

The particular families with this average income have an average transitory income component of zero— some are families with higher permanent income and negative transitory income components, others are families with lower permanent income and positive transitory income.

The average permanent income of such families is, nevertheless, 0D—equal to their average measured income. These families have an average permanent consumption 0H, which, since the transitory elements of their consumption are randomly distributed, averaging to zero, is also their average measured consumption.

But families having measured income below the average—for example, having measured income 0A—will include a higher than average proportion of families whose transitory income components are negative. Low income families include many victims of temporary bad luck, just as high income families include many with temporary windfalls.

The average permanent income of families having measured income 0A is 0B. Here AB is negative transitory income. How do we know it? Because that is the average permanent income necessary to produce permanent consumption (equal to average measured consumption) of 0G assuming zero transitory consumption.

If we merely relate measured consumption to measured income we wrongly associate consumption 0G with income 0A Similarly those with measured income 0F have average permanent income 0E (with positive transitory’ income), producing average permanent (equal to average measured) consumption 0I. The apparent consumption function is C = a + bY, with an MPC considerably below APC. Instead, in the true basic function, which is affected only by long-term income change, APC = MPC.

This approach implies that consumers do not respond equally to all income shocks. If a change in income appears permanent (such as being promoted to a secure and high-paying job), people are likely to consume a large fraction of the increase in income. On the other hand if the income change is clearly transitory (for example, if it arises from a one-time bonus or a good harvest), a significant fraction of the additional income may be saved.

According to PIH, long-term consumption may also be related to changes in a person’s wealth, in particular, the value of his (her) house over time. The economic significance of the PIH is that in the short run the level of consumption may be higher (or lower) than that indicated by the level of current disposable income.

The Life Cycle Hypothesis (LCH):

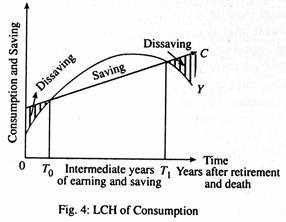

The LCH of Franco Modigliani and Richard Brumberg (1954) has made use of estimates of non-human wealth and substitutes for human wealth based on variables, such as current labour income and this income times the unemployment rate. The lifecycle approach has been most popular in analysing data on individual households in which age, marital status, and demographic variables play an important role.

The LCH suggests that current consumption is not dependent solely on current disposable income but is related to a person’s anticipated lifetime income. For example, a young worker may purchase durable goods such as a car or a house on extended credit because he (she) expects his (her) total income to rise as he (she) moves up a salary scale or obtains an increment in basic wage and thus will be able to pay future interest and repayment charges. By contrast, an older worker nearing retirement may limit his consumption from current income in anticipation that his income will fall after retirement.

In truth, LCH assumes that people save in order to smooth their consumption over their life time. One important objective is to have an adequate retirement income. Hence, people tend to save while working, so as to build up a reserve fund for retirement and then spend out of accumulated savings in their rainy days. One implication of the LCH is that a programme of social security which provides a generous income supplement for retirement will reduce saving by middle aged workers since they no longer need to save much for retirement.

The LCH provided a micro foundation in individual behaviour for the observed patterns of national saving. According to Keynes, the APS—the ratio of saving to income—increases as household income increases and yet empirical evidence shows no tendency for the saving rate to rise as all households get richer.

In the PIH saving is a fraction, not of actual current income, but of expected lifetime income. It provides one way of reconciling cross-section data with time series data on savings. The LCH which holds that individuals save during their earning years and ‘dissave’ after retirement provides another micro foundation of aggregate consumption behaviour.

The Ando Modigliani model based on demographic characteristics suggests that in the early years (T0) of a person’s life, the first shaded portion of Fig. 4, the person is a net borrower. In the middle years he saves to repay debt and provide for retirement. In the late years, he dissaves, as is shown by the second shaded portion.

The basic theme of the hypothesis is simple: although all households consume their incomes over the life-cycle, a growing economy produces a positive amount of total savings because youthful savers are richer and more numerous than retired dissavers; given some assumptions about population growth and life expectancies, this argument yields a constant ratio between saving and income. Thus, the LCH which makes the proportion of income saved depends on lifetime average income, thus making saving relatively insensitive to current income.

The life-cycle model developed by Modigliani Ando, and Brumberg represents an attempt to deal with the way in which consumers dispose of their income over time, and in that model wealth is assigned a crucial role in consumption decisions. In the life-cycle model, wealth includes not only property (houses, stocks, lands, savings accounts, etc.) but also the value of future earnings.

Thus, consumers visualize themselves as having a stock of initial wealth, a flow of income generated by that wealth over their lifetime and a target (which may be zero) for their end-of-life-wealth. Consumption decisions are made with that whole series of financial flows in mind.

Thus, changes in wealth, as reflected by unexpected changes in earnings, profits or unexpected movements in asset prices, would have an impact on consumer spending decisions because they would enhance future earnings from property or labour or both. The theory has empirically testable implications for the age pattern of saving, and for the role of wealth in influencing aggregate consumer spending.

The PIH stressed stochastic variation in income and consumption over time and viewed saving in terms of a bequest motive. The LCH stressed predictable variations in income (and consumption) over the life-cycle and viewed saving as resulting from the greater wealth and number of young savers in comparison to older dissavers.

Bequest Motive Vs. Social Security:

The PIH relates pure consumption to the perpetuity stream that could be consumed forever. The agent is a family whose life is infinite and whose generations are linked by financial transfers from parent to child or vice versa. Saving arises to equate the ratio of the marginal utility of present and future consumption to the marginal rate of transformation implicit in market (real) interest rates as is shown by the typical Fisher model of Inter-temporal choice. In this way, the PIH is said to emphasise the bequest motive for earning.

In contrast, the LCH assumes that individuals consumed their entire endowments over their lifetime. Saving was supposed to arise because young workers were more numerous and wealthy (due to technological progress) than the older generation who were dissaving to finance retirement.

This provides an avenue by which faster growth can increase saving. Alternatively, factors, such as social security, which change the extent of mismatch between lifetime consumption and income patterns are predicted to have profound effects on the aggregate saving.

Differently put—while applying the LC approach, it has been assumed that bequests are zero. Although all income is consumed over an individual’s life, aggregate saving results in a growing economy, because young savers are richer and outnumber retired savers. Recent evidence indicates that bequests are a very larger source of aggregate saving in the USA.

As with retirement saving, bequests are a source of aggregate saving in a growing economy so that individuals can accumulate to leave a larger estate than they inherit (i.e., net intertemporal wealth transfer). The assets which are bequeathed serve as a general reserve during their own lifetime. So precautionary motives as well as concern for heirs explain their size.

A further important determinant of the amount of consumption is wealth. The fact that higher wealth leads to higher consumption is called the wealth effect. And, according to both PIH and LCH, long-run consumption may also be related to changes in a person’s wealth—in particular the value of his house over time.

According to both the PIH and LCH, permanent consumption is a fraction (variable in principle but rarely in practice) of wealth or permanent income. In this context, wealth includes human as well as non-human capital and permanent income is (conventionally constant) long- term ex ante real interest rate times this wealth.

Econometric Estimation of Income:

Friedman proposed a computationally simple estimate of permanent income as geometrically weighted average of past income. Since, in terms of Friedmen’s methodology, permanent income changes—besides normal growth—by a fraction, of the difference between current income and permanent income, Friedman related this scheme to the adaptive expectations approach adopted by Phillip Cagdn.

Modigliani and his associates proxied normal labour income by current income and the product of this variable and the unemployment rate and attempted to measure non-human wealth from the national income accounts at market value. In principle, this method seemed to be more consistent with the conventional national accounting framework than Friedman’s permanent income proxy.

But, in practice, it suffered from three practical problems:

(i) Major components of non-human wealth had no market valuation

(ii) The wealth estimates were not part of the national income accounts and competing variants were available, with substantional delay at irregular intervals; and

(iii) Substantial additional equations were required to forecast (even partly) future movements in wealth.

Empirical work on consumption functions has often been based on the theories of pure consumption to explain data which are—in whole or part—consumer expenditures. Both PIH and LCH were theories of pure consumption. Modigliani and Ando provided one link to consumer expenditures in estimating MPC by modeling household investment in durable goods analogous to firm’s investment behaviour.

The PIH and LCH evolved to explain aggregate consumer expenditures by wealth as a determinant of pure consumption and by changes in wealth and other variables which determine household investment in durable goods. The correlation of the determinants of this household investment with short-run (transitory) fluctuations in income explains the MPC which is substantial in magnitude even though substantially below the APC.

Liquidity Constraint:

Both PIH and LCH has omitted the issue of liquidity constraint (LC). In truth, the substantial value of the MPC reflects liquidity constraints which prevent substantial proportion of consumers (measured by wealth and consumption) from following their optimal Inter-temporal consumption plan. In the presence of LC, Keynes’ AIH is more relevant than PIH and LCH.

Essay # 5.

Rational Expectations of Consumption Function:

Robert Hall (1978) sidestepped Friedman’s backward-looking measure of wealth as well as substantial empirical problems involved in measuring the market value of wealth. Instead, he posed the question of whether or not changes in consumption can be modeled empirically, as determined by official announcements of government policy through the press.

To be more specific, the assertion is that if wealth estimates and, hence, consumption, are based on rational expectations, no past information including past changes in consumption or income should affect current changes in consumption.

Hall nearly turned the PIH around by arguing that current consumption is proportional to current permanent income. So changes in consumption can occur only if there are changes in permanent income and consumption due to planned saving. Hall emphasised that variability in consumption growth must reflect unexpected changes in wealth over the observation period.

Although the hypothesis proved appealing, it has been less successful empirically. This difficulty is probably explained by a more general difficulty in applying the basic optimising hypothesis in order to explain actual consumer expenditures over any given period.

In principle, the optimising hypothesis is strictly applicable only to the consumption of service flows that is, to purchases of non-durable goods and services, plus the rental value (net purchases) of durable and semi-durable goods and services. This differs from Keynes’ consumption concept (consumption expenditures for all goods and services) which is of interest in macroeconomic models.

The national income accounting system of a country reflects Keynes’ concept, and these changes in consumption reflects variations in household investment in durable and semi-durable goods as well as changes in permanent income. The intractability of this problem may explain the limited success in practical application of the rational expectations version of the PIH.

Essay # 6.

Consumer Expenditure and Consumption:

Empirical studies confirmed that excess sensitivity of spending to changes in wealth appeared to be confined to consumers’ purchase of durable goods. These studies confirmed the basic Friedman-Modigliani conjectures that aggregate consumption is determined by wealth, but it is important to distinguish between consumer expenditure and consumption.

PIH treats consumption decisions as based on a long-run concept of income than receipts during some arbitrary accounting period, such as a year. But in the Friedman model, consumption (defined as the using up of goods and services, not their acquisition) is being analysed, not consumer expenditures.

Thus, the permanent income literature has little to say directly about the causes of cyclical variation in consumer spending unless permanent income is itself affected by cyclical change—in which case the desired stock of durables will change, and net investment or disinvestment in durables will occur.

Essay # 7.

Ricardian Equivalence:

Statistical studies also suggest that intergenerational linkages are indeed very important as assumed by the PIH. The life-cycle effect highlighted in the LICH would seem to be more important for analysing cross-section data than as determinants of aggregate consumption. The Ricardian equivalence idea revived by R. Barro assumes that bonds and taxes have equivalent effect on consumer behaviour; so Ricardian equivalence is a quite acceptable and working hypothesis.

Essay # 8.

Real Balance Effect of Consumption Behaviour:

The major unresolved issue related to long-run consumption behaviour is the empirical importance of the real balance effect (RBE). The RBE refers to higher levels of real money balances causing higher consumer expenditures for given values of other variables. Some economists have argued that this would occur because money (at least legal tender money) is a component of wealth missed in permanent income and other measures of wealth.

Others have explained the RBE in terms of substitution for money to consumer durable goods during the adjustment to an unexpected change in the money supply. Traditional Keynesian economists have been skeptical of both views. This is a topic requiring substantially more empirical research.

Finally, very little work has been done on the cyclical characteristics of consumer bahaviour. Keynes noted that the relation between consumption and income depends on, among other things, expectations, optimism and other psychological phenomena. Keynes downgraded the empirical importance of such phenomena for consumers, essentially arguing that they tended to level out (although psychological factors played a major role in Keynes’ investment theory).

Essay # 9.

Conclusion to Consumption Function:

The consumption function hypothesis suggested by Keynes provides a useful challenge to theoretical and empirical economists. The relationship between changes in consumer expenditures and current income has been explained generally in a way which is consistent with microeconomic fluctuations and also adequate in multitudes of specifications for most of the forecasting purposes.

For analytical purposes, two key questions remain unanswered:

1. Are life-cycle effects significant in the aggregate?

2. Are individuals affected by government policies (such as social security measures) in their consumption (saving) decisions?

The consumption function has faded as a topic of intense research largely due to the emergence of the rational expectations hypothesis which has given birth to Hall’s forward-looking theory of consumption function. However, certain crucial issues remain unsettled and have profound policy implications.