In this article we will discuss about Mahalanobis heavy industry biased strategy of development with its criticism.

At the time of the formulation of the Second Five Year Plan, Prof. Mahalanobis prepared a growth model with which he showed that to achieve a rapid long-term rate of growth it would be essential to devote a major part of the investment outlay to building of basic heavy industries. Mahalanobis strategy of development emphasising basic heavy industries which was adopted first of all in the Second Plan also continued to hold the stage in Indian planning right up to the Fifth Plan which was terminated by the Janata Party Government in March 1978, a year before its full term of five years.

It will be useful to explain first Mahalanobis model of growth which provided a rationale for the heavy industry biased development strategy. An important point to note is that Mahalanobis identifies the rate of growth of investment in the economy not with rate of growth of savings as is usually considered by the economists but with rate of growth of output in the capital goods sector within the economy. The growth of capital goods sector in turn depends upon the proportions of total investment allocated to the capital goods sector and output-capital ratio in the capital goods sector.

Given the output-capital ratio in capital goods sector (i.e. heavy industries), he proves that if the proportion of total investment allocated to the capital goods is relatively greater, the rate of growth of output of capital goods will be greater and hence, given the Mahalanobis assumption, the future rate of growth of investment in the economy will be greater. Now, the greater the rate of investment, the greater will be the long-term rate of growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

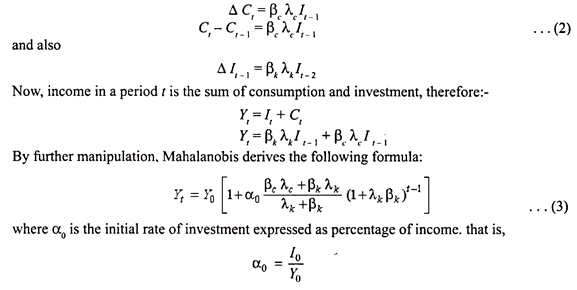

We thus see that with the rate of growth of output of capital goods industries. Mahalanobis shows that the proportion of total investment resources allocated to the capital goods industries, for each year is the most important factor determining the long-term rate of growth of national income. Let us represent his two-sector model in the mathematical form.

In his basic two-sector model Mahalanobis divides the economy into two sectors—the sector C produces consumer goods and sector K produces capital goods. Let –

t0 = Initial rate of investment.

λk and λc =Proportions of total investment allocated to capital goods and consumer goods sectors respectively.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Therefore λk + λc = 1

βk and βc = Marginal output-capital ratio in the capital goods and consumer goods sectors respectively. In other words, they represent ratio of increment of income to investment in the sector K and sector C respectively.

Y0, C0, I0 = The national income, consumption and investment in the base period.

Yt, Ct, lt = The national income, consumption and investment respectively in period t.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Mahalanobis model, the net investment in any period can be divided into two components; the one λk, It, going to capital goods sector K and λc It going to consumer goods sector C. Therefore it follows that-

It= λK It+ λc It

Let ∆It stands for increase in investment (i.e., addition to the stock of capital goods) and ∆Ct for increase in consumer goods in any period t depend on the net investment in the previous period t-1. Now, given the output-capital ratios, βk and βc of the capital goods and consumer goods sectors respectively, the relationship between investment and the resultant increment in output in capital goods can be worked out as –

∆It = βk λkIt-1 or It-It-1=βk λk It-1………………. (1)

This implies that the increase in investment in period t is equal to the increment in output of capital goods. The increase in output of capital goods (βk λk It-1 )in period t is given by investment in period It-1, multiplied by the proportion of it going to capital goods sector (λk) and the output-capital ratio (βk) in the capital goods sector.

It is clear from above that Mahalanobis takes into account only the physical aspect of investment and makes it dependent on the proportion of investment allocated to capital goods sector λ k and output-capital ratio βk in the capital goods sector.

Similar to equation (1) we can also write –

Rationale of Mahalanobis Growth Model:

It is worth noting that Mahalanobis recognises that output-capital ratio βc in the consumer goods sector is greater than the output-capital ratio βk in the capital goods sector. If this is the case, then it apparently implies that growth of output or income will be greater if more investment is made in the consumer goods sector. But in this case the higher rate of growth of income will be only in the short run. As growth equation (3) above shows that after a critical range of time, the larger the investment allocated to capital goods industries, (λk), i.e., the higher will be growth in output or income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Elaborating this point Prof. Raj states, “The logic here is the same as the more common proposition that a higher rate of investment (i.e., a larger proportion of the productive factors used for accumulation) would result in a smaller volume of output being available for consumption in the short run but that over a longer period, it would result in higher rate of growth of consumption; the difference is that the choice is here stated as between investment in capital goods and investment in consumer goods industries.”

The rationale of Mahalanobis growth model and development strategy can be expressed in simple words without mathematical language. According to Mahalanobis, rate of economic growth depends upon the capital formation or real investment. The greater the rate of capital formation, the greater will be the rate of economic growth. The rate of capital formation in an economy, according to Mahalanobis, depends upon the capacity of the economy to produce capital goods.

Thus, according to him, given a closed economy, the rate of real capital formation depends not upon the savings of the economy but on the capacity to produce capital goods. Even if the rate of savings was substantially raised in order to accelerate the rate of capital formation, it would be futile, for required capital goods would not be there if there is a lack of capacity to produce capital goods. Of course, this is based on closed economy assumption.

Thus, according to him, if large investment is not made in the basic heavy industries producing capital goods, the country will forever remain dependent on foreign countries for the imports of steel and capital goods like machinery for real capital formation. Since it is not possible for India to earn sufficient foreign exchange by increasing exports, the capital goods cannot be imported in sufficient quantities owing to foreign exchange constraint.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The result will be that the rate of real capital formation and the rate of economic growth in the country will remain low. Thus, Mahalanobis was of the opinion that without adequate investment in basic heavy industries, it would not be possible to achieve rapid self-reliant economic growth. Therefore, according to him, to achieve rapid economic growth and self-reliance, it would be necessary to give the highest priority to basic capital goods industries in the development strategy of a plan.

Employment Generation in Mahalanobis Model:

It is necessary in this connection to mention Prof. Mahalanobis’ views on increasing employment opportunities and to achieve a stage of full employment. According to him, productive employment can be increased only by increasing the production of capital goods like steel, electricity, machinery, fertilizers, etc. Whether it is increase in employment in the industrial sector or in the agricultural sector, it cannot be achieved without increasing the output of capital goods.

To quote him, “The only way of eliminating unemployment in India is to build up a sufficiently large stock of capital which will enable all unemployed persons being absorbed into productive capacity. Increasing the rate of investment is, therefore, the only fundamental remedy for unemployment in India.” Thus, in Prof. Mahalanobis’ opinion, not only to achieve the objective of rapid economic growth but also to achieve the goal of full employment, it is necessary to accord high priority to capital goods industries in the development strategy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Import-Substituting Industrialisation:

Mahalanobis’ emphasis on basic heavy industries was also due to his objective of meeting the requirements of higher rate of capital accumulation from within the economy and therefore enabling the economy to stop imports of foreign capital equipment and machines. To quote him, “The proper strategy would be to bring about a rapid development of the industries producing investment goods in the beginning by increasing appreciably the proportion of investment in the basic heavy industries. As the capacity to manufacture both heavy and light machinery and other capital goods increases, the capacity to invest by using domestically produced capital goods would also increase steadily and India would become more and more independent of the imports of foreign machinery and capital.” In fact, Mahalanobis growth model advocates import- substitution type of industrial development strategy.

It is important to note that Mahalanobis assumed though implicitly that export earnings of India cannot be sufficiently increased. If this assumption is not valid, as has been pointed out by several critics, then he could not justifiably identify rate of investment in the economy with the domestic output of capital goods. If exports of a country can be adequately raised, the various capital goods can be imported in exchange for exports. In that case rate of investment or rate of capital accumulation in the economy can be stepped up without giving high priority to the basic heavy industries provided the exports can be adequately increased. Thus, the assumption of stagnant exports is crucial in the Mahalanobis growth model for providing the rationale for a general shift in the investment pattern to the domestic production of capital goods.

Mahalanobis Growth Model and Development Strategy in India’s Five Year Plans:

Mahalanobis heavy industry first strategy of development was put into actual practice in India’s Five Year Plans beginning from the Second Plan. India started planned development of its economy in 1951 when First Five Year Plan was started. However, the Five Year Plan did not propose any explicit strategy of development; it took over several projects which had been worked out earlier and some of them were already in the process of being carried out.

It laid emphasis on stepping up the rate of saving and therefore investment and growth by maintaining the marginal rate of saving at a substantially higher level than the average rate of saving. Although it did not present any explicit formulation of development strategy regarding the pattern of investment, its emphasis was on agriculture, irrigation, power and transport aimed at creating the base for more rapid industrialisation of the economy in the future.

The Second Five Year Plan, based as it was on Mahalanobis growth model, proposed an explicit strategy of development which gave top priority to basic heavy industries. Not only the objectives of rapid rate of economic growth and employment generation but also the aim of self-reliant and self-generating economy were sought to be achieved by “the building up of economic and social overheads, exploration and development of minerals and the promotion of basic industries like steel, machine building, coal and heavy chemicals,” Identifying underdevelopment with dependence on agriculture and thinking industrial growth especially the development of heavy industries, as the core of development underlied the approach and strategy of the Second Five Year Plan.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To quote from Second Plan again, “Low or static standards of living, underemployment and unemployment, and to a certain extent even the gap between the average incomes and the highest incomes are all manifestations of the basic underdevelopment which characterises an economy depending mainly on agriculture. Rapid industrialisation and diversification of the economy is thus the core of development. But if industrialisation is to be rapid enough, the country must aim at developing basic industries and industries which make machines to make the machines needed for further development,”

It is clear from above that in the Second Plan there was clear shift of priorities from agriculture to industries and within industries to basic heavy industries. The logic of Mahalanobis in emphasizing heavy industries was that the growth of basic heavy industries will enable the economy to accelerate the rate of capital formation and therefore economic growth. In fact, he identified the rate of growth of investment in the economy with the rate of growth of output in the capital goods (sector) industries within the economy.

Mahalanobis Four-Sector Model:

Mahalanobis realised that the basic heavy industries being capital-intensive will not ensure rapid expansion of employment opportunities and to bring the employment aspect into sharp focus he put forward a four-sector growth model in which he kept heavy industry sector (i.e. K-sector) intact but divided the C-sector (i.e., consumption goods sector) into three sub-sectors- C1, C2, and C3 (sector C1 represented factory enterprises using mechanised techniques and producing consumer goods; Sector C2 represented the household and small-scale enterprises also producing consumer goods and Sector C3 represented provision of services). It was sector C2 representing households and small-scale industries which in Mahalanobis’ four-sector model was visualised to ensure the increased supply of consumer goods to meet their rising demand for them and also to ensure, being labour-intensive, expansion of employment opportunities.

In keeping with this approach, Second Five Year Plan put restrictions on the growth of capacity in factory enterprises engaged in commodity production. However, since for these household or cottage enterprises, adequate resources were not provided, nor any effort was made to improve their productivity, they could neither fulfill their target of production of consumer goods nor of generating enough employment opportunities.

In the Third Plan (1961-66) also the strategy of Second Plan was continued as is clear from the following- “In the Third Plan, as in the Second, the development of basic industries such as steel, fuel and power and machine building and chemical industries is fundamental to rapid economic growth. These industries largely determine the pace at which the economy can become self-reliant and self-generating.” Though, “to achieve self-sufficiency in food-grains and increase agricultural production to meet the requirements of industry and exports” was stated to be one of the objectives of the Third Plan, actual allocation of resources between agriculture and other sectors did not exhibit any difference from that of the Second Plan. Therefore, the concern for food and agriculture in the Third Plan appears to be mere verbal and was not built into the strategy of development.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Fourth Five Year Plan (1969-74) which was prepared under the Deputy Chairmanship of Late Prof. D.R.Gadgil, tried to give new shape to the planning strategy and emphasis was sought to be placed on the common man, the weaker sections and the less privileged. However, the Fourth Plan slightly raised the allocation of Public Sector outlay to agriculture and irrigation to about 23 per cent as against 20 per cent in the Second Plan and the Third Plan, and a good deal of hang over of the heavy industry biased strategy still prevailed in this Plan too.

Despite all talk of Garibi Hatao and direct attack on poverty which preceded the formulation of the Fifth Plan, in the Fifth Plan allocation of public sector investment to agriculture and irrigation was once again reduced to about 20 per cent and the same old heavy industry bias prevailed in the Fifth Plan’s development strategy.

Criticisms of Mahalanobis Heavy-Industry Strategy of Development:

Mahalanobis’ ‘heavy industry first’ strategy of development has come in for severe criticism right from the time of formulation of the Second Plan. First, a serious mistake in Mahalanobis model is that he identified investment with saving. That indicates lack of knowledge of economics. Economists have been emphasizing especially in the context of developing countries that increase in the rate of investment is governed by the increase in the rate of savings. If planned investment is not matched by savings, then inflationary gap will emerge which will cause prices to rise.

It is bad economics to identify investment with savings. Savings in an economy are determined by behavioural characteristics of the decision-making units such as households, the corporate sector and the Government. Saving by the households depends upon the propensity to consume which in turn depends upon various subjective and objective factors. Savings by the corporate sector depend upon the policies regarding depreciation, distribution of dividends and undistributed profits. Savings of the Government are governed by its policies regarding taxation and consumption expenditure, efficiency and profitability of public enterprises.

Thus, when the planning authority allocates relatively more resources to heavy capital goods industries, as is envisaged in Mahalanobis growth model, it will lead to more physical investment or growth of capital stock. But there is no guarantee that savings, governed as they are by various behavioural characteristics of decision-making units, will rise to the level of planned investment. Therefore, by envisaging higher rate of physical investment without considering how savings of the community could be raised to the planned investment, Mahalanobis model contained built-in inflationary potential.

Therefore, being unmatched by savings to fulfill the investment targets of the plan, recourse in actual practice had to be made to deficit financing. No wonder that due to the existence of inflationary gap in India’s Five Year Plans prices began to rise from the very beginning of the Second Plan so much so that during the Fourth Plan period (1969-74) rate of inflation assumed serious proportion reaching as high as about 30% during 1973-74, the last year of the Fourth Plan.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A crucial weakness of Mahalanobis heavy industry strategy of development was pointed out by Professors Vakil and Brahmananda. They criticised heavy industry strategy in their now well-known joint work, “Planning for an Expanding Economy.” According to them, growth of national income and employment is determined by the supply of wage goods. They pointed out that when disguised unemployed are employed in productive work on the wage basis, the demand for wage goods will increase and unless the adequate amount of wage goods are not available, disguised unemployed and openly unemployed cannot be put to work on the wage basis.

According to them, there exists a wage-goods gap in underdeveloped countries like India and the basic cause of unemployment and disguised unemployment in them is the existence of this wage-goods gap. Wage goods act as a constraint on the growth of industrialisation and non-agricultural growth. Thus, in the determination of growth of income and employment, while Mahalanobis emphasised ‘fixed capital’, Brahmananda and Vakil laid stress on the wage goods which are also called ‘circulating capital’. Vakil and Brahmananda put forward a growth model in which wage goods played a key role. Accordingly, they suggested a developed strategy in which top priority was given to agriculture which produces most important form of wage goods, i.e., food-grains.

There is no doubt that Mahalanobis “heavy industry” strategy overlooked the importance of agriculture or wage goods in the growth process of the economy. This manifested itself in the rapid rise of prices from the very beginning of the Second Plan. While a relatively large investment in the basic industries resulted in the creation of money incomes and consequently in a large increase in demand for wage goods, the supply of wage goods did not adequately increase due to the continued neglect of agriculture in India’s planning strategy.

This caused imbalance between demand for and supply of wage goods which has been responsible for inflationary situation in the Indian economy. The continued neglect of wage goods in the development strategy of Indian Plans, right up to the Fifth Plan, is quite surprising since, as pointed out above, this weakness of the strategy was pointed out by Professors Vakil and Brahmananda at the time of the formulation of the Second Plan.

The larger allocation of resources to the basic heavy industries deprived agriculture (including irrigation) and rural industries of enough resources required for their growth. It is now well known as brought out by Professor Lipton, B.S. Minhas that India’s Five Year Plans beginning from the Second Plan, based as they were on Mahalanobis growth model with its emphasis on heavy industries, suffered from ‘relative neglect of agriculture’. The view that there has been relative neglect of agriculture in Indian Plans has been forcefully and effectively expressed and provided by Professor Michael Lipton.

He writes – “We have seen that neither allocations of public money, nor incentives to the movement of persons and other resources, have favoured agricultural development; that 70 per cent of the workers get less than 35 per cent of investment finance and a far smaller share of human skills. Several types of pressures on opinion and policy have combined to bias the allocation of cash, effort, personnel and research away from rural needs.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Like Professor Lipton, B.S. Minhas also holds as similar view about relative neglect of agriculture in Indian Planning. He thus states, “In practical terms the most unfortunate consequences of our adherence to this philosophy of development has been the appalling neglect of agriculture and rural development”. Before Lipton and Minhas, Professors C.N. Vakil and P.R. Brahmananda, have been consistently expressing the view about the low priority assigned to agriculture since the beginning of Second Plan. Recently, C.H. Hanumantha Rao has also deplored the neglect of agriculture in the strategy of Indian Plans. He writes, “The failure of the present strategy to step up public investment for agricultural development has accentuated the problem of unemployment in rural areas.”

A serious failure of Mahalanobis development strategy with its emphasis on basic heavy industries is that it failed to generate adequate amount of employment opportunities. Pattern of industrialization has been based on capital-intensive technology imported from abroad and has been oriented towards urban large-scale industries. If the emphasis were on rural-oriented industrialization promoting cottage and small-scale industries, using intermediate technologies, the problem of surplus labour and unemployment would not have been as acute as it is now.

Besides this, attention was not paid to absorb labour in the agricultural sector, and the agricultural development strategy that could absorb more labour in productive employment was not adopted. Necessary technological and institutional changes for designing such an agricultural strategy required to create more employment were not in actual practice made. Many land reform measures, apart from abolition of big Zamindars and Jagirdars, remained mostly on paper. Legislations regarding tenancy reforms and ceiling on land holdings were not actually enforced and implemented. Being highly capital-intensive the basic heavy industries have themselves created very little employment opportunities.

It is no doubt that certain products of heavy industries such as fertilizers, steel, cement, etc. are certainly required for the growth of agriculture, especially in the context of new agricultural technology and should, therefore, be produced, but Mahalanobis strategy envisaged achievement of self-sufficiency all along the line, involving production of highly sophisticated machines to make machines.

This autarchic nature of Mahalanobis development strategy has been rightly criticised. B.S. Minhas rightly writes, “The logic of the Heavy Industry First Strategy in India sprouted from a number of philosophical riddles. One important conundrum runs as – should you import food, or import fertilisers to produce food at home? Rather than import fertilisers, should you not import fertiliser materials and machinery in order to make fertilisers at home? But why import fertiliser machinery? Should you not import machines to make fertiliser machinery at home? On and on goes the riddle. ”

In view of the limited resources available for investment, the inclusion of highly capital-intensive industries producing machines and mother machines, exhaust a great deal of resources, leaving relatively little for agriculture and rural industries which contain large employment potential. Therefore, in our view, in initial stages of development some intermediate products, machines, and capital goods should be imported if they are urgently needed for some industries, even if in their case, we possess comparative advantage in the dynamic context.

However, it needs to be emphasised again that the form of capital is crucial for employment generation. What required is the small and simple types of machines and tools which are required for the growth of agriculture and small-scale rural industries. The production of these types of capital goods such as fertilizers, pesticides, cement which will help in raising agricultural production and employment need to be expanded. Some large-scale industries, if their large size is necessary in view of technological considerations, should play a supporting role to the development of agriculture and rural industries. Thus, the strategy of growth in India should be reoriented so that agriculture and rural industries constitute the main thrust of the development effort.

From the foregoing analysis, it follows that if the mounting unemployment problem is to be tackled the strategy of development adopted need to be revised and modified. In the new strategy, agriculture has to play a key role in generating enough employment opportunities for a long time to come. The fact that 68 per cent of the Indian labour force and majority of the unemployed and underemployed reside in the rural areas and further that the employment potential of the industries of large-scale type is very little, the promotion of agricultural and rural development must be made the springboard and the leading sector for generating productive employment for millions. Therefore, the strategy for agricultural development should be such as will absorb productively the largest possible number of workers.

Another weakness of the “heavy industry first” strategy and development was that it chose pattern of investment with higher capital-output ratio. In basic heavy industries capital-output ratio was admittedly high and in agriculture and related activities, capital-output ratio was low. Thus, the highest priority to basic heavy industries and low priority to agriculture in the pattern of investment meant the choice of high macro-value of incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR). As has been made clear that if a higher growth rate is desired, given the initial value of a rate of saving and annual increments therein over the projected period, then the criterion should be to choose a pattern of investment with a lower macro-value of capital-output ratio. In the case of India, this would have implied a high priority to be given to agricultural and related sectors over a long period of time.

Therefore, the choice of the pattern of investment containing a high priority to basic heavy industries and low priority to agriculture meant a low rate of economic growth. As has been pointed out above, Mahalanobis and others supporting his strategy contended that their strategy would ensure high rate of growth in the long run. But in actual practice even after 25 years (1956-80) Mahalanobis development strategy of 1955-56 failed to ensure more than 3.5 per cent average annual rate of growth. In the meantime people suffered a lot due to the inflation generated by the strategy and the non-availability of requisite amount of essential consumer goods.

Mahalanobis heavy industry strategy suffers from another weakness in that it heavily depends upon foreign exchange requirements. Though the strategy assumed that exports from the Indian economy could not be sufficiently increased, it required a large amount of foreign exchange resources to establish a network of heavy capital goods industries which required the imports of capital equipment and machinery on a large scale from other countries. For a self-contained growth model framed in the context of a closed economy or stagnant exports, this was an inner contradiction.

This also had two evil effects. Because of the low priority to agriculture and consumer goods industries which had export potentials, export could not rise much, and secondly, due to the highest priority to heavy capital goods industries large imports of capital equipment and materials had to be made. Such was the large requirement of foreign exchange to import capital equipment that despite the liberal foreign aid received from countries, especially the U.S.A.; the country had to face a serious foreign exchange crisis.

It was said in the defence of the heavy industry strategy that it would ultimately help in substituting imports of heavy industrial products such as steel, cement, various kinds of machines, fertilizers etc. This implies that import substitution when accomplished would enable the economy to dispense with foreign aid. However, it was said that in the meantime aid was required to import equipment and materials to set up heavy capital goods industries. Thus it was claimed that the heavy industry strategy envisaged getting “aid to end aid”.

However, the fact remains that far from moving the economy towards self-reliance, the heavy industry strategy increased the dependence on foreign aid. Because of low priority to agriculture in the strategy, production of food-grains did not increase adequately and as a result the imbalance between population and food-grains further increased during the planning period. In order to correct this imbalance food-grains had to be imported on a large scale from other countries.

Whereas the imports of food-grains into India during the First Plan period were of the order of 12 million tones, it rose to 17 million tonnes in the Second Plan period. The situation worsened in the Third Plan period as the implementation of heavy industry strategy further proceeded and 26 million tonnes of food-grains were imported during the Third Plan period. During the three years of plan-holiday period (1966-69), the imports of food-grains jumped to 25 million tonnes in three years period. In the Fourth Plan period in which hangover of the heavy industry strategy persisted, food-grains imports continued unabated with the exception of the year 1972. During the six years period 1970-76, 26.4 million tonnes of food-grains were imported.

It is thus clear that the imbalance between food-grains and population was the direct result of the neglect of agriculture in India’s ‘heavy industry first strategy’. Thus the most distressing effect of the strategy was that the country came to be dependent on even food-grains. But for the imports of food-grains under PL 480 and liberal foreign aid which was made available, India could not have been able to implement the Mahalanobis strategy for its inner contradictions and its inappropriateness to the Indian reality would have come to the surface much earlier.

The situation in the beginning of the Fifth Plan, i.e., in 1974, was that India’s large foreign exchange resources were being used to meet the needs of current consumption (i.e., to import food-grains) rather than to import capital equipment and materials to sustain new investment or capital accumulation. Thus for stepping up the rate of capital accumulation and therefore economic growth we came to be dependent on all the three types of commodities – (i) capital equipment, (ii) raw materials, and (iii) food-grains. Thus, despite the objective of achieving self-reliance, the strategy adopted drove the economy away from it. The philosophy of “aid to end aid” proved to be myth.

Heavy industry strategy has also been criticised for its ignoring the relevance of the principle of comparative advantage and the gains to be obtained from specialisation in some selected fields. Mahalanobis formulated his growth model on the assumption that exports could not be expanded sufficiently. With the help of his model he showed that it is through the adoption of the strategy of substituting imports by domestic production of heavy industry products such as steel, fertilizers, various kinds of machines and machines to make machines, heavy chemicals that high long-term rate of growth could be achieved.

Thus Mahalanobis strategy involved industrialisation of import-substitution type. The question whether the new heavy industries would have a comparative advantage or not was not considered as a relevant consideration. The reckless pursuit of import substitution all along the line and accordingly setting up of all basic heavy industries such as steel, fertilizers, heavy chemicals, machine building and also industries which make Machines to make machines (i.e., industries producing mother machines), and so on without considering whether we had comparative advantage in their production.

If we had comparative advantage in some basic heavy industries we should have concentrated our resources and enjoyed advantages of quick specialisation in selected lines rather than thinly spreading our resources on all types of basic heavy industries irrespective of whether we have comparative advantage or not in them caused misuse of scarce investment resources. As seen above, as a result of this strategy of all-round import substitution to build basic heavy industries we came to be dependent on imports from the rest of the world than we ever were or needed to be.

It may also be pointed out that in the Mahalanobis heavy industry strategy alternative policy of development of industries which had large export potential was not at all given any consideration. That supplies of some capital goods could be procured from abroad by development of export industries was ruled out. In this connection it was pointed out by the followers of Mahalanobis that the expansion of India’s exports would mean the decline in its terms of trade.

In our view, the contention that the increase in India’s exports would necessarily mean decline in terms of trade was not justified. In fact, up to 1972 (i.e., before the oil crisis) the terms of trade had been in India’s favour. It may be pointed out that declining terms of trade argument was advanced by supporters of Mahalanobis strategy only after the Mahalanobis model had been accepted and put into actual practice.

Finally, it may be noted that for achieving high long-term rate of economic growth Mahalanobis and later Raj and Sen and Gautam Mathur have laid the greatest stress upon high magnitude of the ratio of incremental plough-back of heavy industry products to the expansion of heavy industries sector itself as compared to all other sectors. This pattern of industrialisation, according to them, would automatically raise the saving-income ratio and generate a high rate of economic growth in the long run.

However this argument is full of deficiencies and infirmities. The all-round development of heavy industry sector and the highest ratio of plough-back of heavy industry products to the heavy industry sector involves, given the scarcity of resources, not only the appalling neglect of agriculture and rural development but also the neglect of the development of export industries and thereby enjoying the benefits of specialisation.