In this article we will discuss about the methods used in economic analysis.

Economics can be a very deductive subject, and economists are used to constructing complicated ‘models’ of human behaviour which begin with a range of assumptions. However, economics is also an empirical subject, using inductive methods to explain observed facts.

Thus the downward sloping demand curve, for example, can be deduced from general assumptions about how people try to maximise their satisfaction from the purchase of goods and services.

On the other hand, demand curves can be built up empirically, that is by observing actual customers reaction to actual price changes, and when market researchers, data collectors gather relevant information, the data can be used inductively to make economic predictions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In practice, it can be very difficult to say where deduction ends and induction begins. The great economist John Maynard Keynes was known as the ‘armchair economist’, because it was said that he never had to leave his study in order to formulate his theories; on the other hand, if his theories had been divorced from reality, then they would not have had the success that they did have in improving the conditions of life for millions of individuals.

The world’s best deducers are also keen observers of human behaviour, and so economists need to use both deduction and induction in their work.

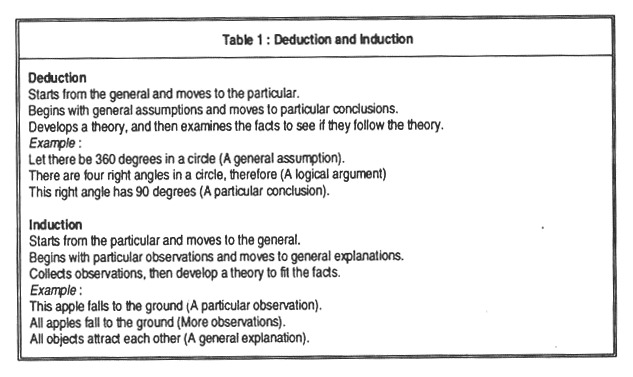

Table 1 explains both of these methods:

Since the deductive method provides an abstract approach to the derivation of economic theories and generalisations, it also goes by the name abstract, analytical and a priori method.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The major steps involved in the method or in the process of deriving economic generalisation through deductive logic are described and explained below:

1. Formulation of the Problem:

In any scientific study, the analyst must have a clear idea of the nature of the problem to be investigated (or enquired into). It is absolutely essential for the analyst or theorist to acquire knowledge of the relevant variables — variables about whose behaviour and interrelationship he wants to make generalisations. The perception of the problem is in most cases a complex exercise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Definition of Terms and Formulation of Assumptions:

Since every subject has its own language, it is necessary to define certain technical terms associated with the analysis as the second step. It is also necessary to make assumptions. The assumptions maybe of different types, viz., technological, relating to the state of technology and factor endowments, or behavioural, relating to the actions of economic agents like consumers, factor owners, and producers.

The assumptions are not made arbitrarily. There should be a logical basis behind them. In other words, the most crucial assumptions are on the basis of actual observations of past events or on the basis of introspection.

For example, two important assumptions made in microeconomic theory are:

(1) The goal of a representative consumer is utility maximisation, and

(2) The objective of a business firm is profit-maximisation.

Similarly, it is assumed that investors seek to strike a balance between risk and return from different projects. Since the most profitable projects are also the most risky ones, investors seek to choose optimum combinations of risks and returns.

Economists also make certain assumptions to simplify the analysis. For example, when they discuss the utility approach to demand theory, they assume that a representative consumer may purchase any number of commodities.

But, when they discuss the indifference curve approach they assume that a consumer buys only two goods (say, food and clothing). This assumption is made just for the sake of convenience, i.e., to make diagrammatic analysis possible. But, we all know that this is an unrealistic assumption. No consumer in the real world buys only two commodities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The real world is no doubt very complex. Numerous factors play their respective roles and interact with one another. So, it is absolutely essential to make simplifying assumptions to bring into focus the relative importance of different factors, which have a direct or indirect bearing on the problem under investigation.

It is not at all necessary for every assumption to be realistic. The most crucial factor in theorising is whether the predictions made by the theory are supported by the facts or observations.

In the words of R. G. Lipsey:

“The scientific approach to any issue consists in setting up a theory that will explain it and then seeing if that theory can be refuted by evidence.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The same point has been made by the Nobel Laureate economist Milton Friedman.

He has explained the view that one should not give undue importance to the ‘realism’ of assumptions. What is most important, from the viewpoint of scientific theory, is whether it enables us to make accurate predictions.

3. Formation of Hypothesis:

The third step in making generalisations through process of logical deduction is to form a hypothesis on the basis of the assumptions made. A hypothesis is a provisional statement the truth of which is not known to us. A hypothesis just describes the relationship among factors affecting a particular phenomenon.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Differently put, it establishes the cause-and-effect relationship among those variables (dependent and independent) having direct bearing on the phenomenon.

A hypothesis is normally deduced from the assumptions, by following a process of logical reasoning verbally or in symbolic terms or by using graphs and diagrams. Any of these techniques may be used to deduce the hypothesis about the relationship among economic variables.

Currently, the process of logical deduction is carried out using rigorous mathematics. As a result, the process of the derivation of the hypothesis no doubt becomes more formal. However, it also becomes more exact.

4. Hypothesis Testing:

The final step involved in the deductive method is hypothesis testing. Hypothesis testing refers to the development and use of statistical criteria to aid decision making about the validity of a hypothesis in uncertain conditions. In any decision about the validity of a hypothesis there is always a chance of making a correct choice and a risk of making a wrong choice.

Hypothesis testing is concerned with evaluating these chances and suggesting criteria that minimise the likelihood of making wrong decisions. Therefore, hypotheses deduced through a process of logical reasoning have to be verified. Otherwise, it is not possible to establish them as generalisations or principles of economic science.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For the testing or verifications of hypothesis economists cannot carry out controlled experiments. Therefore, economists are forced to carry out uncontrolled experiments or rely on past observations. The economic system itself generates necessary information about the behaviour pattern of human beings. Two major problems crop up as a result of uncontrolled experiments.

Firstly, they have to make more and more observations to verify the hypothesis or derive the generalisations. Secondly, the compulsion of relying on uncontrolled experimentations makes the analysis very complicated. Moreover, it becomes absolutely essential to interpret the facts carefully so as to be able to discern the significant relationship among the relevant economic variables.

There are various complexities and difficulties associated with the verification of economic hypothesis through successful analysis and proper interpretations of uncontrolled experiences and past observations. Yet it is encouraging to note that, a number of useful and significant generalisations have been firmly established in the areas of both the branches of economics.

In the area of microeconomics, we may refer to several well-established generalisations such as the direct relation between price and quantity supplied of a commodity, the inverse relation between price and quantity demanded of a commodity, the tendency of profits to tend towards a uniform level among firms under purely competitive conditions, the tendency of wages to equal the marginal revenue product of labour under purely competitive conditions, the tendency of the market price of a product to equal the marginal cost of production of an individual firm in pure competition and so on.

Similarly, in macroeconomics, we may refer to such generalisations as the determination of national output (GNP) by aggregate effective demand and aggregate supply in non-socialist countries, the dependence of a household’s consumption spending on its disposable income the direct relation between the marginal efficiency of capital and the volume of investment and the inverse relation between the rate of interest and the volume of investment, the multiple increase in national income following an initial act of investment, the accelerated effect on investment of a small change in the output or sale of consumption goods and so on.