In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Special Drawing Rights 2. Uses of SDRs 3. Critical Appraisal.

Introduction to Special Drawing Rights:

The main problem which has confronted the international monetary system in the recent decades is to raise the supply of reserves. Although the IMF has been making a fruitful contribution in dealing with the problem of international liquidity, yet its actual working has exposed some of its weaknesses.

The loan operations through the Fund partook of the nature of a disbursal of credit through a revolving fund, the size of which over a short period was fixed. Over the long period, the size of the fund could, of course, grow through the increases in quota or new borrowing arrangements. The IMF, however, was seriously afflicted by its inability to issue its own liability.

Further, the Fund became quite helpless when:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) The high-quota countries exercised their borrowing rights;

(ii) There was a strong demand for the currencies of the few countries that were in a short supply and;

(iii) The countries who could assist in general credit arrangements were themselves in a financial impasse.

Another major weakness of the IMF which had pushed it almost to the precipice was its failure to readjust the domestic monetary and fiscal policies of the countries running into payments difficulties. A large numbers of advanced countries, including the United States, conveniently by-passed any disciplining of domestic monetary and fiscal policies for resolving the payments problems.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In view of the problem of international liquidity, efforts were initiated in September, 1963, when the Group of Ten decided to entrust a committee of officials, the so-called Group of Deputies, with the task of undertaking a thorough examination of the outlook for the functioning of the international monetary system and of its probable future needs for liquidity.

The deliberations of the Group of Deputies culminated in the Ossola Report published in May, 1965 and the Emminger Report published in July, 1966. The Ossola Report described and analysed the proposals for new kinds of liquidity. The Emminger Report dealt with the specific positive proposals. During the twelve months between the IMF meetings of 1966 and 1967, the Group of Ten continued its deliberations. In September 1967, in IMF meeting at Rio de Janeiro, an outline for a scheme of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) was pushed forward.

Several steps were required before the plan could be put into operation. The amendments to the IMF Articles of Agreement were submitted to the members in 1968 and the draft amendments had been ratified by July 1969. In September 1969, the managing directors and the executive directors of the IMF made a formal proposal for allocation of SDRs over the ensuing three years. The first allocation of $ 3.5 billion was made on January 1, 1970, followed by more allocations from time to time.

SDRs or the so-called ‘paper-gold’ are simply entries in the books of accounts of the participant countries in the Special Drawing Account of the IMF. All the members need not be participants. There is, however, liberal scope for the opting-in and opting-out. The participants get Special Drawing Rights allotted to them on the basis of their relative quotas of the IMF.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The SDRs constitute a net creation of world’s supply of international monetary reserves. It is just like the discovery of gold. Just as gold can be readily exchanged with any currency, so can be the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). That is the reason why it is called as the ‘paper-gold’.

Originally one SDR was considered equivalent to 0.88671 gram of gold which was the value of one U.S. dollar. Subsequent to the abandonment of the system of par values of currencies and floating of U.S. dollar and other major currencies in 1973, it was decided to determine the value of SDR on the basis of a basket of 16 most widely used currencies of the United states, Britain, Germany, Japan, France, Canada, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Australia, Spain, Norway, Austria, Denmark and South Africa.

In 1978, the currencies of Denmark and South Africa were excluded and those of Saudi Arabia and Iran were included. Each of these currencies was assigned weight in proportion to its importance in international trade and world financial markets. With the object of facilitating proper valuation of a unit of SDR, the number of currencies in the basket was reduced from 16 to 5 in January 1981. These currencies included the U.S. dollar, the German deutsche mark, the British pound, the French franc and the Japanese yen.

Beginning with January 1986, the currency composition of the basket of currencies and weightage to be assigned to each currency in the basket for the evaluation of a unit of SDR was to be revised every five years. The revision of value of SDR is to be made on the basis of value of exports and balances of currencies held with the IMF by the member countries. At the end of 1988, one SDR was equivalent to 1.346 U.S. dollar.

During 1991-95 period, the currencies and their share in the total weight were as follows in the evaluation of SDR- 40 percent for the U.S. Dollar, 21 percent for Deutsche Mark, 17 percent for the Japanese Yen, and 11 percent each for Pound Sterling and French Franc. The SDR valuation was modified by the IMF after the launch of the Euro. German Deutsche Mark and French Franc in the SDR valuation basket have been replaced with equivalent amounts of Euro.

With effect from January 1, 1999, the value of SDR is determined by the sum of the following amounts of each currency- 27.2000 of Japanese Yen, 0.5821 of U.S. Dollar, 0.2280 of Euro (Germany), 0.1239 of Euro (France) and 0.1050 of Pound Sterling.

With the Second Amendment in 1978, SDR became the international unit of account. A precise mechanism has been evolved to operate the SDR scheme. A country that requires convertible foreign exchange resources has to apply to the IMF for the use of SDRs. It can use its SDRs upto the limit of allocation to it.

On the receipt of such an application, the Fund notifies this requirement to another country whose BOP and gross reserve position are sufficiently strong. This country is regarded as the ‘designated’ country. On its giving the consent for it, the book entries in the Special Drawing Account of each of the two countries are made and the required currency is made available to the borrowing country.

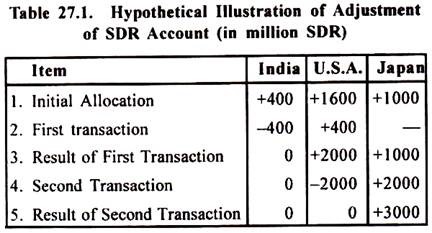

This transfer of SDRs and the adjustment mechanism between the different countries can be illustrated with the help of a hypothetical example. It is supposed that there are three countries— India, U.S.A. and Japan and the IMF create SDRs amounting to SDR 3000 million. It is further supposed that IMF allocates quotas as SDR 400 million, SDR 1600 million and SDR 1000 million for India, U.S.A and Japan respectively. Now suppose India has a deficit with the U.S.A. of the amount of 400 million dollars.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It notifies IMF for conversion of its SDRs holding into the U.S. dollar. IMF will ask the United States to accept SDR 400 million from India in exchange of 400 million U.S. dollars. As the United States intimates its acceptance, the transaction will be complete. The result is shown in Row 3 of Table 27.1.

When the first transaction is complete, the SDR holding of India becomes zero while that of the U.S.A. rises to + 2000, Japan’s holding remaining unchanged at SDR 1000 million. It is again supposed that the United States has a deficit equivalent to SDR 2000 million to be paid in terms of Japanese currency. The United States will notify the IMF of its intention to convert its SDR holding into yen. The IMF will intimate Japan of it.

As Japan gives its acceptance, an amount equivalent to SDR 2000 million will be debited from the U.S. holding and the accumulation of Japan will rise by 2000 million SDR. As the second transaction is complete, the result is shown by Row 5 of Table 27.1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This row shows that the SDR holdings of India and the U.S.A. are zero and the holding of Japan has accumulated to SDR 3000 million. It is therefore clear that the IMF acts like a clearing house between the central banks of the participating countries and all adjustments in BOP disequilibrium are affected through book-entries.

On all SDR holdings kept in the Special Drawing Account, the IMF has to pay interest and it charges interest at the same rate on all allocations made to participants. The participants whose holdings exceed their allocations earn net interest. Those participants, in case of whom the holdings fall short of their allocations, have to pay net charges at the current interest rate.

Originally the SDR interest rate was set at 1.5 percent per annum in 1969. On July 1974, it was hiked upto 5 percent per annum and was retained at that level until July 7, 1975. Subsequently, it was decided to make half-yearly adjustments in it on the basis of half of combined market rate on the basket of currencies. It has been set quarterly to the full combined market rate since 1st July 1976. It has been set at 14.04 percent per annum with effect from 1st July, 1985.

In the beginning IMF created SDR 9.3 billion over the three years between 1970 and 1972 allocating them to 112 participants in the SDR scheme. In 1978, the Fund raised them by SDR 4 billion in each of the years 1979, 1980 and 1981. In 2009, SDR allocations to the member countries were of the order of SDR 217 billion.

Uses of SDRs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are three principal uses of SDRs.

These are as follows:

(i) The first use of SDRs is in transactions with designation. The IMF designates a participant in the SDR scheme with strong and favourable balance of payments and reserve position to provide its currency in exchange of SDRs to another participant who requires its currency. The currency that is to be exchanged with SDRs may belong either to the designated country or/and to some other countries. The lending countries are permitted to accept SDRs in this way so long as their holdings are less than three times their total allocations.

(ii) The SDRs are used in all transactions with the IMF.

(iii) The SDRs are used also in the transactions by agreement. The IMF permits the sale of SDRs for currency by agreement with another participating country in the scheme.

Apart from the above principal uses of SDRs, there are certain other uses of this facility.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These include:

(iv) Through the Second Amendment, the IMF is empowered to employ SDRs for some more uses which were earlier not specified. The additional uses of SDRs include – (a) Swap arrangements operations, (b) forward operations, (c) granting and receiving of loans, (d) settlement of financial disputes. (e) Security for financial obligations and (f) granting of donations.

(v) The Fund has empowered, besides the World Bank and its associates, some other agencies like the Bank for International Settlements, the African Development Bank, the Arab Monetary Fund, Nordic Investment Bank etc. to acquire and use SDRs in transactions and operations by agreement under the same terms and conditions as applicable to the participating nations in the SDR scheme.

The efforts are afoot to employ SDRs to a greater extent as a unit of account in the international financial markets and in private transactions.

Critical Appraisal of SDR Scheme:

The SDR has emerged as a new form of international monetary reserve. It has attempted to free the international monetary system from its excessive dependence upon the U.S. dollar and complication created by the fluctuations in international gold prices. This innovation has been made essentially to tackle the difficult situation created by the acute shortage of international liquidity for adjusting the BOP deficits of the member countries of the IMF.

The countries participating in SDR scheme receive SDRs under “transactions with designation” and “transactions by agreement” unconditionally. They are not required to change their domestic economic policies as they are supposed to do under the IMF assistance programme. In contrast to other IMF financing facilities, the system of payments and repayments of SDRs is easier and more flexible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The SDR arrangement is a sort of grafting on the existing international monetary system without causing any disturbance or dislocation.

The SDR scheme represents a serious effort to replace gold as the pivot of international monetary reserve system. Even though SDRs or paper gold may not completely replace gold, yet it will be a useful and flexible supplement to the existing reserves and credit facilities.

The SDR arrangement undoubtedly has several merits, yet it has been subjected to criticism on several grounds which are detailed below:

(i) Inequitable Scheme:

Since the allocation of SDRs to the member countries is made on the basis of their subscription quota, therefore, the major portion of SDRs are made available to the developed countries. The share of LDCs is very low compared with their international reserve requirements. The scheme is clearly not equitable and restricts the capacity of the developing countries to borrow funds for offsetting their payments deficits and to finance the programme of their development.

(ii) No Link with the Need for Development Finance:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The present SDR arrangement is not satisfactory from the point of view of the less developed countries because it does not link the creation of international liquidity reserves in the form of SDRs with their requirement of development finance.

The need for international liquidity on the part of developing countries is great because of their chronic BOP deficits, mounting external debt burden, shortage of domestic capital, internal inflation, limited access to private banking and capital markets, variability in export earnings and limited access to the markets of advanced countries for their exports.

In these circumstances, there is urgent need to create not only more SDRs, but there should also be need-based rather than quota-based distribution of these reserves. If the SDRs are allocated on the basis of low per capita incomes rather than the GNP or subscription quotas, the distribution system of SDRs can become more equitable. In addition, there should not be rigid adherence to stiff conditionality. The larger flow of SDRs on an unconditional basis may be ensured to the less developed countries.

In this connection, the Report of Brandt Commission, published in February 1983 made highly significant recommendations:

(a) There should be a substantial new Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) allocation with particular attention to the needs of developing countries.

(b) There should be at least a doubling of IMF quota.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) There should be an emergency borrowing authority to support developing countries through enlargement and reform of the General Arrangement to Borrow (GAB).

(d) There should be increased borrowing from central banks and borrowing from capital markets.

(e) There should be an enlargement and improvement of the compensatory finance facility.

The attitude of advanced countries, however, remains a major stumbling block in the reform or rationalisation of SDR scheme on the lines favourable to the less developed countries.

(iii) Rescue Operation for Dollar:

Sometimes the SDR scheme is criticised on the ground that it seems to be a rescue operation for the dollar. The scheme was initiated at a time when the United States dollar was under severe pressure. The scheme was meant to save the over-valued dollar from the logical consequence of devaluation. Later on, the linkage of SDR value with the basket of world’s major currencies was again intended to relieve pressure off the United States dollar.

(iv) Rate of Interest:

A serious objection against the SDR scheme was that the rate of interest on SDR borrowing was extremely low at just 1.5 percent. It remained at that level until June 30, 1974. Between July, 1974 and July 7, 1975 it stood at only 5 percent. Subsequently, the provision was made for six monthly adjustments at the level half of the combined market rate on the basket of currencies.

The low rate of interest on SDRs, it was alleged, and induced deficit countries to use SDRs in preference to other reserve assets to finance their deficits. The surplus countries, on the other hand, were less eager to accumulate the SDRs. Since July 1, 1985, the rate of interest on SDR borrowing was set at 14.04 percent per annum and the above objection no longer remained valid.

(v) Excessive Reliance on Capital Markets:

In the face of increasing need for the international liquidity, IMF has to depend greatly for the generation of more and more international monetary reserves or SDRs upon the international capital markets. This has led to the charging of higher interest rate on SDR borrowing and the introduction of stiffer conditionality.

(vi) No Pressure to Take Corrective Measure:

If deficit countries borrow funds from other financing facilities of the IMF, they are subject to conditionality and are under pressure to adopt specified measures for correcting the BOP deficit. However, the SDR scheme has limited potential for application of pressure on a country to undertake corrective measures to offset balance of payments deficit.

(vii) Unreliable Source:

The availability of borrowed reserves is unreliable during periods of greatest need of reserves. The system has to be modified in such a way that the countries should rely with confidence upon SDR facility for tackling their adverse balance of payments position.

The IMF arrangements, including SDR facility, continue to remain far short of the expectations of the poor countries which continue to remain tormented by multiple problems like shortage of development finance, BOP deficits, low growth, internal inflation, rising unemployment, mounting external debt burden and trade barriers.

No doubt, efforts are afoot to evolve such arrangements that should adequately resolve the liquidity problems, but the future alone would tell as to what extent they prove to be successful in tackling international monetary and payments problems. In this context Scitovsky said, “A true solution, however, of our monetary problems must await a reformed attitude and an international division, not only of labour and its benefits, but of adjustment burdens as well”.