In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to the Ricardian Theory of Rent 2. Assumptions of the Ricardian Theory of Rent 3. Explanation and Illustration 4. Criticisms.

Introduction to the Ricardian Theory of Rent:

David Ricardo, an English classical economist, propounded a theory to explain the origin and nature of economic rent. He defined rent as “that portion of the produce of the earth which is paid to the landlord for the use of the original and indestructible powers of the soil.” In his theory, rent is nothing but the producer’s surplus or differential gain and it is found in land only.

At the time of Ricardo land was primarily used for agriculture; now it is mainly used for residences, offices and stores. But the most important full of land is the same even today: the supply of land and be increased by paying a higher price or its supply diminished by offering a lower price.

The price of using a piece of land for a period of time is called its rent, or more specifically, pure economic rent. In our daily usage the term ‘rent’ refers to the price paid per unit of time (month, year, etc.) for the service of durable goods like a machine, or a car or a building. This is known as contract (commercial) rent.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But in economics, the term has a specific meaning. Economic rent is a surplus income — excess of total payments to a factor of production (land, labour or capital) over and above its minimum supply price or opportunity cost (i.e., what is required to bring the particular factor into production).

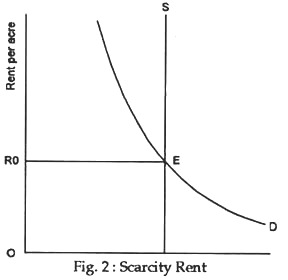

As early as 1817 David Ricardo applied the idea of rent to agricultural land only. The notion of paying rent applies to land is fixed in supply. In Fig. 2 s the downward sloping derived demand curve for land intersects completely inelastic supply and at E to determine rent per acre, i.e., the price that has to be paid for using the service of land for a specific period. So, scarcity of land as a factor of production gives rise to rent. If rent rose above the equilibrium level, the amount of land demanded by all the farmers would be less than the existing amount that would be supplied.

Since some landowners would not be able to rent their land at all, they would have to offer their land for the less price and thus bid down its rent. In a like manner, the rent could not remain below the equilibrium level for long. If it did, bidding of unsatisfied farms would drive the price of land back toward the equilibrium level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Only at a competitive price where the total amount of land demanded exactly equals the fixed supply will the market be in equilibrium. As Paul Samuelson has put it, “Rent is the payment for the use of factory of production that are fixed in supply. Because the supply of land is inelastic, land will always risk for whatever a competition gives it. Thus, the value of the land derives entirely from the value of the product, and not vice versa”.

The notion of rent applies to any factor of production that is fixed in supply. For example, Leonardo Da Vinci’s portrait of Mona Lisa is unique; if one weds it for an exhibition, one would be paying rent for its temporary use. He classified lands into different categories and argued that lands were cultivated in descending order of fertility.

Initially, the more productive (fertile) land was cultivated and, as the demand for corn (wheat) grew, less fertile (inferior grades of) land were brought under cultivation. He assumed constancy of labour costs and return on capital. The price of corn was equal to the cost of production on the marginal (high cost) land.

Since land was not homogeneous, a surplus was earned on superior land over the marginal land due to differences in fertility. This surplus was called economic rent. According to Ricardo, “rent is that portion of the produce of the earth which is paid to the landlord for using the original and indestructible powers of the soil.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Ricardian theory of differential rent is illustrated in Fig. 3. There are three plots of land, A, B and C ranked by descending fertility or increasing marginal cost (which – equals average costs). A is low cost land, B is medium cost land and C is high cost land. The marginal cost curve is the thick line CDEFGMC, which looks like a staircase. When price of wheat is P1 only plot A is cultivated. Since price equals average cost, there is no surplus or rent. When price is P2 plot B is brought under cultivation.

Now there is surplus on plot A land as indicated by the shaded area Thus, rent is a producers’ surplus — the surplus above cost. But, for plot B price is just sufficient to cover cost of production, leaving neither a surplus nor a deficit at the end.

But as price rises to P3, plot C is also brought under the plough. Since plot C is high cost land, there is no surplus on this land. But there is a surplus on plot B as shown by the shaded area 3. At the same time, the surplus from plot A increases and is now given by the two areas 1 and 2.

Relation between Rent and Price:

At the time of Ricardo’s writings, the price of wheat in England was rising due to Napoleonic wars. Most people blamed landlords for the high price of wheat which was thought to be result of high rent charged by the landowners. Ricardo however argued that the rent of land was high because the price of wheat was high. The converse was not true. His argument was simple: Since the price of wheat was equal to the cost of production on the marginal (no rent) land, rent did not enter the price.

So, taxing the landlords could have hardly any effect on the price of wheat. In the language of Samuelson, “Since the supply of land is fixed, the rent for a plot of land depends totally on the demand curve for the land. Suppose the land can be used only to grow corn. If the demand for corn rises, that will cause the demand curve for the corn land to shift up and to the right, and the rent will rise.”

Scarcity Rent vs. Differential Rent:

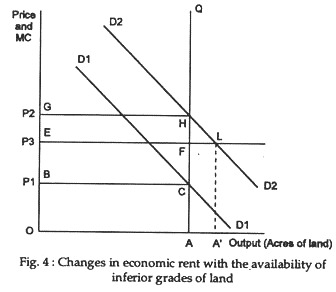

It is important to note that the emergence of rent does not depend on the existence of inferior grades of land. It arises due to scarcity of fertile land. In fact, due to the availability of inferior grades of land, the rents of superior grades of land did not increase appreciably (i.e., increase to the extent warranted by the market forces). This point is illustrated in Fig. 4. We measure output on the horizontal axis and price and marginal cost on the vertical axis. Since we assume constant output per acre, we also denote acres of land on the horizontal axis.

Suppose, the amount of fertile land available in an area is OA, and this is all of equal fertility (Now we make the assumption that land is homogeneous). The marginal cost (= average cost) of this land is OB. The marginal cost (= average cost) of this land is OB. The supply curve is BCQ. When the demand Curve D1D1, the entire land area (which is fertile land) is brought under cultivation.

Since Pa = MC, there is no rent. However, with population growth, the demand curve shifts to D2D2. The price rises to P2 and since the marginal cost of production is P1, a surplus of P1P2 HC above cost is generated. This accrues to landlords as rent. This is what happens if there is no other land available for cultivation.

Now suppose, inferior grades of land are also available. The marginal cost (= average cost) of production now is OE. Now when demand increases, price will rise only to P3 (= OE). Output would go up from OA to OA’ and the rent on the fertile land would be given by the area of the rectangle BCFE.

Thus, with economic progress when inferior grades of land are bought under the plough rent (producers’ surplus) falls.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, it is clear that rent arises not only due to differences in the fertility of the soil, but due to scarcity of fertile land as well. Rent will exist whether or not inferior land is cultivated. However, if the demand curve shifts to the left to D1D1 price will still be P1 (= marginal cost OB), in which case, all the fertile land will not be used.

Intensive vs. Extensive margin:

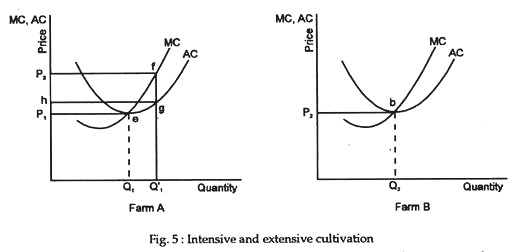

Ricardo also pointed out that with an increase in price of wheat production there would be need for both intensive and extensive cultivation, i.e., more wheat would be produce on the same plot of land and less fertile land would also be brought under cultivation. This point is illustrated in Fig. 5 where we draw the normal U-shaped and MC and AC curves. Here we consider only two farms, farm A (low cost farm) and farm B (high cost farm).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When price is P1 only farm A is cultivate. Output is Q1. Since price = MC = AC, rent is zero. When price rises to P2 due to rise in demand, the volume of production increases from Q1 to Q’1 due cultivation of the same lot or of the intensive margin.

Now, rent of BAP2C is generated. But when price rises, farm B is also brought under cultivation. Its output is Q2. This is the extensive margin. But, price is just sufficient to cover cost of production of farm B. So, rent is not paid (since the equilibrium point D is the break-even point).

Thus, in a sense all rent is differential rent. In another sense, all rent is scarcity rent. The two theories (or two parts of Ricardian theory) that we have discussed above are different but interrelated. This is why Alfred Marshall has rightly commented that “all rents are scarcity rents and all rents are differential rents”.

Marshall, of course, generalised the concept and suggested that what is true of land or natural resources is equally true of certain types of machines, man-made assets and special human skills. He used the term ‘quasi-rent’ to depict the surplus accruing to the factors of production other than land.

Assumptions of the Ricardian Theory of Rent:

Some assumptions are implied in the Ricardian Theory of Rent. These are:

(a) Rent of land arises due to the differences in the fertility or situation of the different plots of land. It arises owing to the original and indestructible powers of the soil.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Ricardo assumes the operation of the law of diminishing marginal returns in the case of cultivation of land. As the different plots of land differ in fertility, the produce from the inferior plots of land diminishes though the total cost of production in each plot of land is the same.

(c) Ricardo considers the supply of land from the standpoint of the society as a whole.

(d) In the Ricardian theory it is assumed that land, being a gift of nature, has no supply price and no cost of production. So, rent is not a part of cost, and being so it does not and cannot enter into cost and price.

Explanation and Illustration of the Ricardian Theory of Rent:

According to Ricardo, rent of land arises because the different plots of land have different degree of productive powers; some lands are highly fertile and some lands are less fertile. So, there are different grades of land. The difference between the produce of the superior lands and that of the inferior lands is rent, what is called differential rent.

Similarly, there may be differences in the situation of the different plots of land. Lands favourably situated (say, near the market) have greater advantages than those which are not so situated (say, far away from the market). The surplus enjoyed by the former over the later is also differential rent or situation rent.

Let us illustrate these two cases of differential rent:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Differential Kent on account of differences in the fertility of land:

Ricardo assumes that the different grades of land are cultivated gradually in descending order — the first grade land being cultivated at first, then the second grade land, after that the third grade and so on. With the increase in population and with the consequent increase in the demand for agricultural produce, inferior grade of lands are cultivated, creating a surplus or rent for the superior land areas.

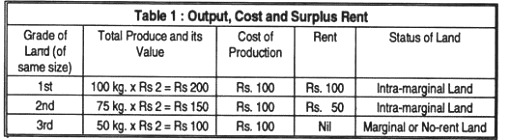

This point is illustration in the following table:

The table shows the position of 3 different plots of land of equal size. Let us assume that the order of cultivation reaches the 3rd stage when all the 3 plots of land of different grades are cultivated and the market price has come to the level of Rs. 2 per kg. of rice. The first grade land, being the most fertile, produces 100 kg., the 2nd grade land produces 75 kg, and the third grade land, being the least fertile, produces only 50 kg, with the same cost in each case.

So, the first grade land has a surplus or rent of Rs. 100, the second grade land has a rent of Rs. 50 and the third one has no surplus. The first two plots are called the intra-marginal and the 3rd one is the marginal or no-rent land. It shows how the differences in the fertility of the different plots of land have been creating rent for the superior lands.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Differential Rent on account of difference in the situation of land:

The differences in the situation of the different plots of land may give rise to situation rent to lands which are favourably situated. Let us suppose that there are two plots of land having the same degree of fertility, but one near the market and the second one far away from the market.

In the case of the latter the transport cost of bringing the produce to the market is Rs. 5 but in the case of the former it is Rs. 2. As the market price covers all costs, the former gets a surplus of Rs. 3 over the latter and the surplus represents the rent of the former. This rent is also known as situation rent.

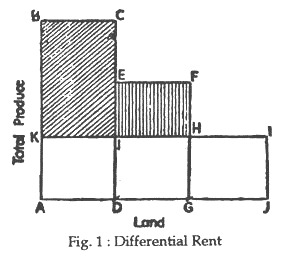

The differential rent on account of differences in the fertility of different plots of land is shown in Fig. 1.

In the figure, AD, DG and GJ are three separate plots of land; each is of the same size, but of different fertilities. The total produce of AD is ABCD that of DG is DEFG and that of GJ is GHIJ. The first and second plots of land have a surplus represented by the shaded area of the produce of each, which represents the rent of those two plots of land. The plot GJ has no surplus and so it is marginal land or no-rent land.

Criticisms of the Ricardian Theory of Rent:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Ricardian theory is criticised on several grounds:

(a) It is pointed out that land does not possess any original and indestructible power, as the fertility of land gradually diminishes, unless fertilizers are applied regularly.

(b) Ricardo’s assumption of no-rent land is unrealistic as in reality every plot of land earns some rent, high or low.

(c) Ricardo restricted rent to land only, but modem writers have shown that rent arises in any factor of which the supply is inelastic.

(d) According to Ricardo, rent does not and cannot enter into cost and price, but from the individual point of view rent forms a part of cost and price.

(e) Ricardo’s order of cultivation of lands is also not realistic.